Jmmv2201.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: O’Keeffe, Mornee Jasmin (1991) Over and under: geography and archaeology of the Palm Islands and adjacent continental shelf of North Queensland. Masters Research thesis, James Cook University of North Queensland. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/5bd64ed3b88c4 Copyright © 1991 Mornee Jasmin O’Keeffe. If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please email [email protected] OVER AND UNDER: Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland Thesis submitted by Mornee Jasmin O'KEEFFE BA (QId) in July 1991 for the Research Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts of the James Cook University of North Queensland RECORD OF USE OF THESIS Author of thesis: Title of thesis: Degree awarded: Date: Persons consulting this thesis must sign the following statement: "I have consulted this thesis and I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author,. and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which ',have obtained from it." NAME ADDRESS SIGNATURE DATE THIS THESIS MUST NOT BE REMOVED FROM THE LIBRARY BUILDING ASD0024 STATEMENT ON ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: "In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it." Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. -

Royal Historical Society of Queensland Journal The

ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF QUEENSLAND JOURNAL Volume XV, No.l February 1993 THE WORLD OF THE BAMA Aboriginal-European Relations in the Cairns Rainforest Region to 1876 by Timothy Bottoms (All Rights Reserved) Presented to the Society as an Audio-Visual Program 10th August 1991 The world of the Djabugay-Yidiny [Jabuguy-Yidin] speaking people occupied what is now called the Cairns rainforest region. Their term for themselves is BAMA [Bum-ah] — meaning 'people'. To the south are Dyirbal [Jirrbal] speaking tribes who are linguistically different from their northern Yidiny-speakers, as German is to French. There appears to have been quite a deal of animosity' between these linguistically different neighbours. To the north are the Kuku-Yalanji [Kookoo Ya-lan-ji] who seem to have a great deal more in common with their southern Djabugay- speaking neighbours. In the northern half of the Cairns rainforest region are the Djabugay-speaking tribal groupings; the Djabuganydji [Jabu-ganji], the Nyagali [Na-kali], the Guluy [Koo-lie], the Buluwanydji [Bull-a- wan-ji], and on the coastal strip, the Yirrganydji [Yirr-gan-ji].^ The clans within each tribal grouping spoke dialects of Djabugay — so that, although there were differences, they were mutually understandable.^ The southern half of the Cairns rainforest region is home to the linguistically related Yidiny-speaking people. Fifty- three percent of the Yidiny lexicon is derived from Djabugay." However in the same fashion as the Djabugay-speakers — each clan, and there are many in each tribe,^ considered itself an entity in its own right, despite the linguistic affinities. The tribes who spoke Yidiny-related dialects were the Gungganydji [Kung-gan-ji], the Yidinydji [Yidin-ji], the Madjanydji [Mad-jan-ji], and Wanjuru. -

East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery from 1 September 2019 Identified As the East Coast Trawl Fishery (See Schedule 2, Fisheries (Commercial Fisheries) Regulation 2019)

East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery From 1 September 2019 identified as the East coast trawl fishery (see Schedule 2, Fisheries (Commercial Fisheries) Regulation 2019). Status report for reassessment and approval under protected species and export provisions of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) May 2021 This publication has been compiled by Fisheries Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Enquiries and feedback regarding this document can be made as follows: Email: [email protected] Telephone: 13 25 23 (Queensland callers only) (07) 3404 6999 (outside Queensland) Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday: 8 am to 5 pm, Thursday: 9 am to 5 pm Post: Department of Agriculture and Fisheries GPO Box 46 BRISBANE QLD 4001 AUSTRALIA Website: daf.qld.gov.au Interpreter statement The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you need an interpreter to help you understand this document, call 13 25 23 or visit daf.qld.gov.au and search for ‘interpreter’. © State of Queensland, 2021. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. -

Combined Gunggandji People's Native Title Determination

Looking east over the township of Yarrabah from Mount Yarrabah, which forms part of the Combined Gunggandji People’s native title determination. Photo: Leon Yeatman. Combined Gunggandji People’s native title determination 19 December 2011 Far North Queensland Facilitating timely and effective outcomes. Combined Gunggandji People’s determination On 19 December 2011, the Federal Court of Australia made a consent determination recognising the Combined Gunggandji People’s native title rights over country, 6km east of Cairns in Far North Queensland. The determination area covers about 8297ha of land and waters, including the northern part of the Yarrabah Deed of Grant in Trust (‘DOGIT’), including Yarrabah township, the foreshores of Mission Bay, Cape Grafton, Turtle Bay, Wide Bay and Oombunghi beach, part of Malbon Thompson Forest Reserve and two parcels of land on Fitzroy island. The Combined Gunggandji People negotiated with representatives of the Queensland Government, Yarrabah Aboriginal Shire Council, Cairns Regional Council, Ergon Energy Corporation Limited, Black and White (Quick Service) Taxis Pty Ltd, Telstra Corporation Limited, Southern Cross Media Australia Pty Ltd, Seven Network (Operations) Limited, Miles Electronics Pty Ltd and residents of the Yarrabah DOGIT to reach agreement about the Combined Gunggandji People’s native title rights and the rights of others with interests in the claim area. The Gunggandji People also negotiated seven Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) that establish how their respective rights and interests will be carried out on the ground. Parties reached agreement with the assistance of case management in the Federal Court of Australia, ILUA negotiation assistance from the National Native Title Tribunal, and legal representation of the Combined Gunggandji People by the North Queensland Land Council. -

Damari & Guyala Damari & Guyala

SONGLINES ON SCREEN 1 Damari & Guyala • EDUCATION NOTES © ATOM 2016 A STUDYA STUDY GUIDE GUIDE BY MATHEW BY ATOM CLAUSEN http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN:ISBN: 978-1-74295-XXX-X978-1-74295-984-9 http://theeducationshop.com.au 1 Classroom Context DAMARI & GUYALA The activities included in this resource, provide opportunities for students to explore Indigenous Australian cultures, language and stories. The Australian Curriculum has been used as a Introduction guide for the planning of these activities. You should adapt the activities to suit the student age These teachers’ notes have and stage of your class and the curriculum foci and been designed to assist you with outcomes used in your school. classroom preparation in relation Some websites are suggested throughout this resource. It is recommended that you first visit the to the viewing of the short film sites and assess the suitability of the content for Damari & Guyala. This film is one your particular school environment before setting of eight films that have been made the activities based on these. to record, celebrate and share precious historic and cultural information from Indigenous groups in remote Western, CONTENT HYPERLINKS: Northern and Central Australia. We hope that this resource will assist your students to further enjoy and enhance their viewing. The following link provides you with an overview of the other films in theSonglines on Screen series: NITV - Songlines on Screen http://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/songlines-on-screen/ © ATOM 2016 © ATOM article/2016/05/25/learn-indigenous-australian- -

HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406 Hydrographic Department Ministry of Defence Taunton, Somerset TA1 2DN National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Copied: 1987 1 HISTORICAL NOTE The Hydrographical Office of the Admiralty was created by an Order-in-Council of 12 August 1795 which stated that it would be responsible for ‘the care of such charts, as are now in the office, or may hereafter be deposited’ and for ‘collecting and compiling all information requisite for improving Navigation, for the guidance of the commanders of His Majesty’s ships’. Alexander Dalrymple, who had been Hydrographer to the East India Company since 1799, was appointed the first Hydrographer. In 1797 the Hydrographer’s staff comprised an assistant, a draughtsman, three engravers and a printer. It remained a small office for much of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, under Captain Thomas Hurd, who succeeded Dalrymple as Hydrographer in 1808, a regular series of marine charts were produced and in 1814 the first surveying vessels were commissioned. The first Catalogue of Admiralty Charts appeared in 1825. In 1817 the Australian-born navigator Phillip Parker King was supplied with instruments by the Hydrographic Department which he used on his surveying voyages on the Mermaid and the Bathurst. Archives of the Hydrographic Department The Australian Joint Copying Project microfilmed a considerable quantity of the written records of the Hydrographic Department. They include letters, reports, sailing directions, remark books, extracts from logs, minute books and survey data books, mostly dating from 1779 to 1918. They can be found on reels M2318-37 and M2436-67. -

Great Southern Land: the Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis

GREAT SOUTHERN The Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis LAND Michael Pearson the australian government department of the environment and heritage, 2005 On the cover photo: Port Campbell, Vic. map: detail, Chart of Tasman’s photograph by John Baker discoveries in Tasmania. Department of the Environment From ‘Original Chart of the and Heritage Discovery of Tasmania’ by Isaac Gilsemans, Plate 97, volume 4, The anchors are from the from ‘Monumenta cartographica: Reproductions of unique and wreck of the ‘Marie Gabrielle’, rare maps, plans and views in a French built three-masted the actual size of the originals: barque of 250 tons built in accompanied by cartographical Nantes in 1864. She was monographs edited by Frederick driven ashore during a Casper Wieder, published y gale, on Wreck Beach near Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague, Moonlight Head on the 1925-1933. Victorian Coast at 1.00 am on National Library of Australia the morning of 25 November 1869, while carrying a cargo of tea from Foochow in China to Melbourne. © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Heritage Assessment Branch Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. -

Supplementary Synthesis Report: Connectivity and Inter-Dependencies of Values in the Northeast Australia Seascape Supplementary Report (Part 2)

Final Report Supplementary Synthesis Report: Connectivity and inter-dependencies of values in the northeast Australia seascape Supplementary Report (Part 2) Johanna E. Johnson, David J. Welch, Paul A. Marshall, Jon Day, Nadine Marshall, Craig R. Steinberg, Jessica A. Benthuysen, Chaojiao Sun, Jon Brodie, Helene Marsh, Mark Hamann and Colin Simpfendorfer Supplementary Synthesis Report: Connectivity and inter-dependencies of values in the northeast Australia seascape Supplementary Report (Part 2) Johanna E. Johnson1,2, David J. Welch1,3, Paul A. Marshall4,5, Jon Day6, Nadine Marshall7, Craig R. Steinberg8, Jessica A. Benthuysen8, Chaojiao Sun7, Jon Brodie6, Helene Marsh1, Mark Hamann1 and Colin Simpfendorfer9 1 School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University 2 C2O Consulting, Cairns, Australia 3 C2O Fisheries, Cairns, Australia 4 The Centre for Biodiversity & Conservation Science, University of Queensland 5 Reef Ecologic, Townsville, Australia 6 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 7 CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Crawley, Australia 8 Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia 9 Centre for Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture, James Cook University, Townsville Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program Project 3.3.3 Connectivity and interdependencies of values in the northeast Australian seascape © James Cook University, 2018 Creative Commons Attribution Supplementary Synthesis Report: Connectivity and inter-dependencies of values in the northeast Australia seascape is licensed by James Cook University for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925514-24-7 This report should be cited as: Johnson, J.E., Welch, D.J., Marshall, P.A., Day, J., Marshall, N., Steinberg, C.R., Benthuysen, J.A., Sun, C., Brodie, J., Marsh, H., Hamann, M., Simpfendorfer, C. -

Queenslandregion

Society for Growing Australian Plants (Queensland Region) Inc. Cairns Branch PO Box 199 Earlville Qld 4870 Newsletter No. 100 June 20 10 Society Office Bearers Chairperson Tony Roberts 40 551 292 Vice Chairperson Mary Gandini 40 542 190 Secretary David Warmington 40 443 398 Treasurer Robert Jago 40 552 266 Membership Subscriptions- Qld Region - Renewal $30.00, New Members $35, each additional member of household $2.00 Student - Renewal $20 New Members $25.00, Cairns Branch Fees - $10.00 Full Year To access our Library for the loan of publications, please contact David Warmington Newsletter Editor: Tony Roberts [email protected] Dates to remember Cairns Branch Meetings and Excursions – third Saturday of each month. NEXT MEETING AND EXCURSION 19/20 June 2010 at Cooktown. Tablelands Branch Excursion– Sunday following the meeting on the fourth Wednesday of the month. Any queries please contact Chris Jaminon 4095 2882 or [email protected] Townsville Branch General Meeting Please contact John Elliot: [email protected] for more information Crystal Ball Cooktown June - Cooktown The next outing is to Cooktown. The routine July - White Mountains will follow the established format for Cooktown Aug - Redden Island visits: Work 8.30 till 4 Saturday and 8.30 till Sept – Upper Harvey Ck midday Sunday. Could members attending Oct - Barron Falls’ boardwalk/Kuranda please contact Pauline on 4047 1577 for further Nov - Ellie Point details and so that she can provide numbers before hand . June 2010 Page 1 of 29 May Excursion Report The walk began in open woodland with Corymbia citriodora, Eucalyptus crebra & Eucalyptus portuensis. -

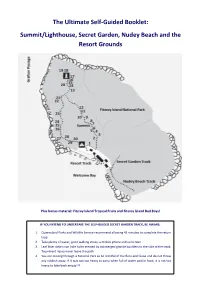

The Ultimate Self-Guided Booklet: Summit/Lighthouse, Secret Garden, Nudey Beach and the Resort Grounds

The Ultimate Self-Guided Booklet: Summit/Lighthouse, Secret Garden, Nudey Beach and the Resort Grounds Plus bonus material: Fitzroy Island Tropical Fruits and Fitzroy Island Bad Boys! IF YOU INTEND TO UNDERTAKE THE SELF-GUIDED SECRET GARDEN TRACK, BE AWARE: 1. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service recommend allowing 45 minutes to complete the return loop 2. Take plenty of water, good walking shoes, a mobile phone and sunscreen 3. Leaf litter debris can hide holes created by submerged granite boulders to the side of the track. To prevent injury never leave the path 4. You are moving through a National Park so be mindful of the flora and fauna and do not throw any rubbish away. If it was not too heavy to carry when full of water and/or food, it is not too heavy to take back empty!!! The information in this booklet is dedicated to all those that have called Fitzroy Island home, from the island’s original inhabitants, the Gunggandji people, to the military and lightkeepers who each played their role in shaping the island’s fate. The Gunggandji were walking these paths before paths existed, living off these trees and surviving in this forest for thousands of years before the first European explorers ever set foot on this land. When war threatened our shores the men of the No. 28 Radar Station stepped up to protect these lands; their influence can still be seen across the island today as can the Lightkeepers that came after them. Each served their country in isolation in lieu of modern comforts. -

Coastal Seagrass Habitats at Risk from Human Activity in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area Review of Areas to Be Targeted for Monitoring

Coastal Seagrass Habitats at Risk from Human Activity in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area Review of areas to be targeted for monitoring Michael Rasheed, Helen Taylor, Rob Coles and Len McKenzie Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries Northern Fisheries Centre, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility Project 1.1.3 Condition, trend and risk in coastal habitats: Seagrass indicators, distribution and thresholds of potential concern © Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries. PR07-2971 This report should be cited as: Rasheed, M. A., Taylor, H. A., Coles, R. G. and McKenzie, L. J. (2007) Coastal seagrass habitats at risk from human activity in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area: Review of areas to be targeted for monitoring. Report to the Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (122 pp.). Made available for download by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited for the Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility. The Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility (MTSRF) is part of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth Environment Research Facilities programme. The MTSRF is represented in North Queensland by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). The aim of the MTSRF is to ensure the health of North Queensland’s public environmental assets – particularly the Great Barrier Reef and its catchments, tropical rainforests including the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, and the Torres Strait – through the generation and transfer of world class research and knowledge sharing. This publication is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, information or educational purposes subject to inclusion of a sufficient acknowledgement of the source. -

JAMES COOK's TOPONYMS Placenames of Eastern Australia

JAMES COOK’S TOPONYMS Placenames of Eastern Australia April-August 1770 ANPS PLACENAMES REPORT No. 1 2014 JAMES COOK’S TOPONYMS Placenames of Eastern Australia April-August 1770 JAMES COOK’S TOPONYMS Placenames of Eastern Australia April-August 1770 David Blair ANPS PLACENAMES REPORT No. 1 January 2014 ANPS Placenames Reports ISSN 2203-2673 Also in this series: ANPS Placenames Report 2 Tony Dawson: ‘Estate names of the Port Macquarie and Hastings region’ (2014) ANPS Placenames Report 3 David Blair: ‘Lord Howe Island’ Published for the Australian National Placenames Survey Previous published online editions: July 2014 April 2015 This revised online edition: May 2017 © 2014, 2015, 2017 Published by Placenames Australia (Inc.) PO Box 5160 South Turramurra James Cook : portrait by Nathaniel Dance (National NSW 2074 Maritime Museum, Greenwich) CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 James Cook: The Exploration of Australia’s Eastern Shore ...................................... 1 1.2 The Sources ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2.1 Manuscript Sources ........................................................................................... 1 1.2.2 Printed and On-line Editions ............................................................................. 2 1.3 Format of the Entries .............................................................................................