C6@;@F:,)-7,Ƒoß=);XB: 7O-BXB: ,Ax-@+XB:,/B+O//,)-7,S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

Los Angeles by Dan Luckenbill

Los Angeles by Dan Luckenbill Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The modern gay civil rights movement may be said to have been born in Los Angeles with the formation of the Mattachine Society and ONE, Inc. in the early 1950s. The glbtq history of the city, now the U.S.'s second largest metropolis, is replete with other cultural, social, and political firsts, with the largest, the best-funded, the Two photographs by longest-lived, and at times the most visible and influential of publications, protests, Angela Brinskele: legal accomplishments, cultural influences, and social and religious organizations. Top: Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa marching in Los Angeles, along with San Francisco and New York, has been at the very center of the 2006 Los Angeles the American glbtq movement for equality. Currently, groups are attempting to Gay Pride Parade. Above: The McDonald/ increase the involvement of racial and ethnic minorities within the city's glbtq Wright Building of the communities. Gay and Lesbian Center in Los Angeles. Maturing of a City Images copyright © 2006 Angela Brinskele, courtesy Angela Until the late twentieth century Los Angeles was often satirized as a place of indolent Brinskele. sunshine, home to a second-rate art form and cult religions. It received scant serious attention when cultural histories were written about U.S. cities. All of this changed when motion pictures became perhaps the most influential art form internationally, when alternative religions came to the forefront, and when it no longer seemed merely hedonistic and mind numbing to enjoy living and working in the beneficent southern California climate. -

Guide to the One Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers

GUIDE TO THE ONE ARCHIVES CATALOGING PROJECT: FOUNDERS AND PIONEERS FUNDED BY THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES ONE NATIONAL GAY & LESBIAN ARCHIVES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GUIDE TO THE ONE ARCHIVES CATALOGING PROJECT: FOUNDERS AND PIONEERS Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Grant #PW-50526-10 2010-2012 Project Guide by Greg Williams ONE NATIONAL GAY & LESBIAN ARCHIVES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES, 2012 Copyright © July 2012 ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives Director’s Note In October 1952, a small group began meeting to discuss the possible publication and distribution of a magazine by and for the “homophile” community. The group met in secret, and the members knew each other by pseudonyms or first names only. An unidentified lawyer was consulted by the members to provide legal advice on creating such a publication. By January 1953, they created ONE Magazine with the tagline “a homosexual viewpoint.” It was the first national LGBTQ magazine to openly discuss sexual and gender diversity, and it was a flashpoint for all those LGBTQ individuals who didn’t have a community to call their own. ONE has survived a number of major changes in the 60 years since those first meetings. It was a publisher, a social service organization, and a research and educational institute; it was the target of major thefts, FBI investigations, and U.S. Postal Service confiscations; it was on the losing side of a real estate battle and on the winning side of a Supreme Court case; and on a number of occasions, it was on the verge of shuttering… only to begin anew. -

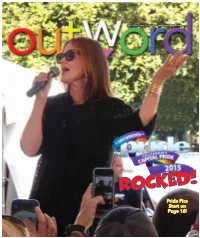

530 • June 11, 2015 • Outwordmagazine.Com

No. 530 • June 11, 2015 • outwordmagazine.com ROCKED! Pride Pics Start on Page 16! COLOR COLOR Lambda Literary Award Winners Announced he winners of the 27th Annual Lambda Literary Awards (the “Lammys”) were announced at a gala ceremony hosted Tby comedienne Kate Clinton, with performances by Lauren Patten of the hit Broadway show Fun Home and Toshi Reagon. Feminist legend Gloria Steinem introduced Rita Mae Brown, author of the classic, Rubyfruit Jungle, who received the Pioneer Award. Describing laughter as “an orgasm of the mind,” she praised Brown for always understanding joy and laughter. It wasn’t a love fest, but a joke fest when gossip columnist Liz Smith introduced filmmaker and author John Waters, who received Lambda’s Trustee Award for Excellence in Literature. In a sign of the transgender coming of age John Waters at the Lambda Literary Awards times in which we’re living, Casey Plett The ceremony was held June 1 at The winner in the Transgender Fiction category Great Hall at Cooper Union in NYC, and for A Safe Girl to Love ended her rousing opened with an animated video by Melanie acceptance speech with, “The transgender La Rosa and Johanna Campos that cleverly community is taking over!” The Betty Berzon symbolized the fundamental elements of the Emerging Writer Awards were presented to Lambda Literary Awards, as it depicted writers Anne Balay and Daisy Hernandez. superheroes saving a town called “Gaytham” For a full list of the winners, visit with literature. www.lambdaliterary.org. Fundraiser Set for Surviving the Silence olonel Pat Thompson, now living in the Sacramento area, was a decorated military nurse, only two years away from Cretirement after an illustrious career when an assignment came the to preside over a hearing regarding a fellow Army nurse’s federal recognition. -

Betty Berzon Papers, 1928-2006 Coll2011.004

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1s2035mf No online items Finding Aid to the Betty Berzon Papers, 1928-2006 Coll2011.004 Finding aid prepared by Loni Shibuyama ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California, 90007 (213) 741-0094 [email protected] © 2011 Finding Aid to the Betty Berzon Coll2011.004 1 Papers, 1928-2006 Coll2011.004 Title: Betty Berzon Papers Identifier/Call Number: Coll2011.004 Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Language of Material: English Physical Description: 66.9 linear feet.39 records boxes + 15 photo binder boxes + 3 archive cartons + 7 flat archive boxes + 1 suitcase + 1 oversize trophy + 1 mapcase drawer. Date (bulk): Bulk, 1965-2005 Date (inclusive): 1928-2006 Abstract: Manuscripts, correspondence, organizational records, research materials, photograph albums, audiovisual items, clothing, trophies and other materials from lesbian activist, writer and psychotherapist, Betty Berzon (1928-2006). Included in this collection are manuscripts and resource materials for Berzon's published and unpublished books; records from gay and lesbian organizations in which she was involved; paper and audiovisual material for her therapy practice, workshops, and training programs; correspondence files; subject files; extensive photo albums and memorabilia documenting Berzon's personal life; and personal papers, including those related to Berzon's relationship with long-time partner, Teresa DeCrescenzo, and Berzon's years-long battle with cancer. creator: Berzon, Betty Biography Betty Louise Berzon was born to a middle-class Jewish family on January 18, 1928, in St. Louis, Missouri. The family moved to Tuscon, Arizona when Berzon was young, and upon graduating high school she attended Stanford University, majoring in journalism and creative writing. -

View of the Literature

THE EFFECTS OF GENDER AND CLIENT SEXUAL ORIENTATION ON COUNSELORS’ ATTITUDES AND SELF-EFFICACY A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Dina L. Miller August 2004 © 2004 Dina L. Miller All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled THE EFFECTS OF GENDER AND CLIENT SEXUAL ORIENTATION ON COUNSELORS’ ATTITUDES AND SELF-EFFICACY BY DINA L. MILLER has been approved for the Department of Counseling and Higher Education and the College of Education by Patricia Beamish Associate Professor of Counseling and Higher Education James Heap Dean, College of Education MILLER, DINA L. Ph.D. August 2004. Counselor Education The Effects of Gender and Client Sexual Orientation on Counselors’ Attitudes and Self- efficacy (155pp.) Director of Dissertation: Patricia Beamish Research examining the effects of client sexual orientation on counselors’ attitudes has focused on clinical judgment biases and diagnostic evaluation. These samples are often counseling students or counselor trainees. Little research has examined practicing counselors’ attitudes toward clients of different gender and sexual orientation using self- efficacy measures. The current study uses a gender stratified national sample of practicing counselors to examine the effects of gender and client sexual orientation on counselors’ attitudes and self-efficacy. The effects of counselors’ general self-efficacy and cognitive complexity are controlled. An experimental design with random assignment is used to group participants into four comparison groups. A client vignette is used differing only by gender and sexual orientation. A semantic differential attitude instrument and three Counselor Self-Estimate Inventory (COSE) subscales are the dependent measures. -

Guide to the ONE Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers

Guide to the ONE Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Guide to the ONE Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Grant #PW-50526-10 2010-2012 Project Guide by Greg Williams ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90007 213.821.2771 [email protected] one.usc.edu © July 2012 ONE Archives at the USC Libraries Director’s Note In October 1952, a small group began meeting to discuss the possible publication and distribution of a magazine by and for the “homophile” community. The group met in secret, and the members knew each other by pseudonyms or first names only. An unidentified lawyer was consulted by the members to provide legal advice on creating such a publication. By January 1953, they created ONE Magazine with the tagline “a homosexual viewpoint.” It was the first national LGBTQ magazine to openly discuss sexual and gender diversity, and it was a flashpoint for all those LGBTQ individuals who didn’t have a community to call their own. ONE has survived a number of major changes in the 60 years since those first meetings. It was a publisher, a social service organization, and a research and educational institute; it was the target of major thefts, FBI investigations, and U.S. Postal Service confiscations; it was on the losing side of a real estate battle and on the winning side of a Supreme Court case; and on a number of occasions, it was on the verge of shuttering… only to begin anew. -

Berzon Prize Applica

1 Dr. Betty Berzon Emerging Writer Award Lambda Literary's Dr. Betty Berzon Emerging Writer Award recognizes LGBT-identified writers whose work demonstrates their strong potential for promising careers. Made possible through a generous gift from Teresa DeCrescenzo, MSW in honor of Dr. Betty Berzon, two Emerging Writer awards will be presented at the 2015 Lambda Literary Awards Ceremony. The award includes a cash prize of $1000. Nominations must be received by December 15, 2014. Qualifications for Nomination The nominee must self-identify as LGBT. The nominee must have written and published at least one but no more than two books (fiction or nonfiction). The nominee must be of demonstrated ability and show promise for continued growth. Important Considerations This award honors emergent writers. Debut and Mid-Career authors are not eligible for consideration. The nominee’s contributions to the LGBT literary field beyond their writings and publications will also be considered. Additional literary work such as short stories and essays, or editing LGBT-themed anthologies collections will also be considered. Individuals may nominate themselves or other writers. All materials must be postmarked by December 15, 2014 Incomplete applications will not be considered. 2 NOMINATION FORM: Please email the following information as a single document to [email protected] 1) Nominee’s name, address, email, and phone number 2) Nominee’s social media presence, as applicable (website, blog addresses, etc.) 3) Nominator’s name, address, email and phone number (if different from above) 4) Your relationship with the nominee 5) List the nominee’s major published works, (up to two books and additional literary work such as short stories, poetry or essays). -

Dr. Betty Berzon Emerging Writer Award the Dr

1 Dr. Betty Berzon Emerging Writer Award The Dr. Betty Berzon Emerging Writer Award will be presented annually at the Lambda Literary Awards ceremony. The award, made possible by Teresa DeCrescenzo, consists of two cash prizes of $1000. 1. The award will be presented to two (2) LGBT-identified authors, and age will not be a factor in defining an emerging writer. 2. The award will recognize LGBT authors who have written and published at least one but no more than two books (fiction or nonfiction). If only one book has been published, additional literary work such as short stories or essays will be considered to substantiate an author’s potential for a promising career. 3. The authors will be of demonstrated ability and show promise for continued growth. 4. Candidates’ contributions to the LGBT literary field beyond their writings and publications will also be considered. * Please keep in mind that the prize is intended for writers who are emergent. * Individuals may nominate themselves or other writers. * All materials must be postmarked by March 7, 2014 2 SUBMITTING A NOMINATION: Please include three (3) complete sets of the following materials: 1) How does the nominee represent the future of LGBT literature? (1000 word maximum) 2) List the nominee’s major published works, (up to two books and additional literary work such as short stories or essays). 3) Anything else you want to add supporting this candidate? (500 word maximum) 4) 3 copies of author’s book(s) that best represents the writer’s work. 5) A maximum of 3 letters of recommendation for the candidate may be e-mailed to Lambda Literary Foundation to support the candidate’s nomination.