Reading and Teaching Gender Issues in Electronic Literature and New Media Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of Electronic Literature. an Overview. As Origens Da Literatura Eletrônica

Texto Digital, Florianópolis, v. 15, n. 1, p. 4-27, jan./jun. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5007/1807-9288.2019v15n1p4 The Origins of Electronic Literature. An Overview. As origens da Literatura Eletrônica. Um panorama. Giovanna Di Rosarioa; Kerri Grimaldib; Nohelia Mezac a Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy - [email protected] b Hamilton College, Clinton, New York United States of America - [email protected] c University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom - [email protected] Keywords: Abstract: The aim of this article is to sketch the origins of electronic literature and to Electronic highlight some important moments in order to trace its history. In doing so we consider Literature. Origins. the variety of languages, cultural backgrounds, cultural heritages, and contexts in which Development. digital literature has been created. The article is divided into five sections: a brief World. history of electronic literature in general (however, we must admit that this section has a very ethnocentric point of view) and then four other sections divided into North American, Latin American, European (Russia included), and Arab Electronic Literature. Due to the lack of information, there is no section devoted to Electronic Literature in Asia, although a few texts will be mentioned. We are aware of the limits of this division and of the problems it can create, however, we thought it was the easiest way to shortly map out the origins of electronic literature and its development in different countries and continents. The article shows how some countries have developed their interest in and creation of electronic literature almost simultaneously, while others, just because of their own cultural background and/or contexts (also political and economic contexts and backgrounds), have only recently discovered electronic literature, or accepted it as a new form of the literary genre. -

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

Sue Thomas, Phd [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE last updated June 2013 Sue Thomas, PhD www.suethomas.net [email protected] Narrative Summary I have been writing about computers and the internet since the late 1980s. My books include ‘Technobiophilia: nature and cyberspace (2013), a study of the biophilic relationship between nature and technology, Hello World: travels in virtuality (2004), a travelogue/memoir of life online, and Correspondence (1992), short-listed for the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. In 1995 I found the pioneering trAce Online Writing Centre, an early global online community based at Nottingham Trent University which ran for ten years. From 2005-2013 I was Professor of New Media in the Institute of Creative Technologies at De Montfort University where I researched biophilia, social media, transliteracy, transdisciplinarity and future foresight, as well as running innovative projects like the NESTA-funded Amplified Leicester, and the development of the DMU Transdisciplinary Common Room, a collaborative space for cross-faculty working. To date I have received funding from Arts Council England, the Arts and Humanities Research Board, the British Academy, the British Council, the EU, the Higher Education Innovation Fund, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, NESTA and many others. My partners have included commercial companies, universities, arts organisations, local authorities and colleagues in Sweden, Finland, France, Australia and the USA. I left De Montfort University in June 2013 to focus on writing and consultancy and I am currently researching future forecasting in nature, technology and well-being. I want to know what practical steps we might take to ensure that our digital lives are healthy, mindful and productive. -

Spring 1986 Editor: the Cover Is the Work of Lydia Sparrow

'sReview Spring 1986 Editor: The cover is the work of Lydia Sparrow. J. Walter Sterling Managing Editor: Maria Coughlin Poetry Editor: Richard Freis Editorial Board: Eva Brann S. Richard Freis, Alumni representative Joe Sachs Cary Stickney Curtis A. Wilson Unsolicited articles, stories, and poems are welcome, but should be accom panied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope in each instance. Reasoned comments are also welcome. The St. John's Review (formerly The Col lege) is published by the Office of the Dean. St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. William Dyal, Presi dent, Thomas Slakey, Dean. Published thrice yearly, in the winter, spring, and summer. For those not on the distribu tion list, subscriptions: $12.00 yearly, $24.00 for two years, or $36.00 for three years, paya,ble in advance. Address all correspondence to The St. John's Review, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Volume XXXVII, Number 2 and 3 Spring 1986 ©1987 St. John's College; All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. ISSN 0277-4720 Composition: Best Impressions, Inc. Printing: The John D. Lucas Printing Company Contents PART I WRITINGS PUBLISHED IN MEMORY OF WILLIAM O'GRADY 1 The Return of Odysseus Mary Hannah Jones 11 God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob Joe Sachs 21 On Beginning to Read Dante Cary Stickney 29 Chasing the Goat From the Sky Michael Littleton 37 The Miraculous Moonlight: Flannery O'Connor's The Artificial Nigger Robert S. Bart 49 The Shattering of the Natural Order E. A. Goerner 57 Through Phantasia to Philosophy Eva Brann 65 A Toast to the Republic Curtis Wilson 67 The Human Condition Geoffrey Harris PART II 71 The Homeric Simile and the Beginning of Philosophy Kurt Riezler 81 The Origin of Philosophy Jon Lenkowski 93 A Hero and a Statesman Douglas Allanbrook Part I Writings Published in Memory of William O'Grady THE ST. -

Indigo Girls the Indigo Girls Amy Ray (Left) and Emily Saliers Performing at by Carla Williams Park West, Chicago, in 2005

Indigo Girls The Indigo Girls Amy Ray (left) and Emily Saliers performing at by Carla Williams Park West, Chicago, in 2005. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Image appears under the Creative Commons Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Attribution ShareAlike Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com License. Photograph by Lesbians Amy Ray and Emily Saliers are Indigo Girls, one of the most successful folk/ Wikimedia Commons pop duos in recording history. Ray and Saliers have carved out an enduring career that contributor Andreac. is due largely to the fierce loyalty of their fans, many of them lesbians. Ray, a native Atlantan, and Saliers, a transplant from Connecticut, met in grade school in Atlanta and became friends. They shared a talent for writing and music and began playing together in Ray's parents' basement. During college at Emory University, they played club dates in and around Atlanta as the "B Band" and later "Saliers and Ray," developing their following and reputation as a particularly strong band in live performance. Beginning in 1981 they released several independent records on tape and in 1985 released a vinyl single, "Crazy Game." That same year Ray selected the name Indigo Girls on "sort of a whim," she explained in an interview years later. "I found it in the dictionary . it's a deep blue, a root--real earthy." The duo signed with Epic Records in 1988. Their first record for Epic, the multi-platinum Indigo Girls, included their best-known song, "Closer to Fine." That year they were nominated for two Grammy awards-- Best New Artist (they narrowly lost to Milli Vanilli) and Best Contemporary Folk Album, which they won. -

Amy Ray Career

A lot of artists defy categorization. Some do so because they are tirelessly searching for the place they fit, while others are constantly chasing trends. Some, though, are genuinely exploring and expressing their myriad influences. Amy Ray belongs in the latter group. Pulling from every direction — Patty Griffin to Patti Smith, Big Star to Bon Iver — Ray's music might best be described as folk-rock, though even that would be a tough sell, depending on the song. Ray's musical beginnings trace back to her high school days in Atlanta, Georgia, when she and Emily Saliers formed the duo that would become the Indigo Girls. Their story started in 1981 with a basement tape called “Tuesday's Children” and went on to include a deal with Epic Records in 1988, a Grammy in 1990, and nearly 20 albums over more than 30 years. Rooted in shared passions for harmony and justice, the Indigo Girls have forged a career that combines artistry and activism to push against every boundary and box anyone tries to put them in. As activists, they have supported as many great causes as they can, from LGBTQ+ rights to voter registration, going so far as to co-found an environmental justice organization, Honor the Earth, with Winona LaDuke in 1993. As artists, they have dipped their toes into a similar multitude of waters — folk, rock, country, pop, and more — but the resulting releases are always pure Indigo. Ray's six solo sets — and three live albums — have charted even wider seas, from the political punk of 2001's Stag to the feminist Americana of 2018's Holler. -

Learning As You Go: Inventing Pedagogies for Electronic Literature

Learning as you go: Inventing Pedagogies for Electronic Literature. In a field like electronic literature, which is both well developed and always emerging, most teachers have faced the challenge of teaching material that is regarded as “marginal” within the Humanities but relevant in the classroom. Though the scholars that circulate around the organization tend to be very interested in literary approaches, most have found themselves working in roundabout ways, slipping electronic literature into literature surveys, media studies, fine arts, and computer science classrooms. Indeed, as Maria Engberg notes in her survey of electronic literature pedagogy in Europe, there are a range of institutional obstacles to the teaching of electronic literature, and these obstacles differ depending on national, institutional, and disciplinary contexts. Citing Jorgen Schafer’s experience teaching eliterature in Germany, Engberg points to the various places where electronic literature can fit into a broader curriculum: “1) literary studies; 2) communications or media studies; 3) art and design schools or creative writing programs; and 4) computer science departments.”i In response to the scant attention to electronic literature in German academic settings, Shafer’s recommendation is “to ‘reanimate’ the so-called Allgemeine Literaturwissenschaft (or ‘general study of literature’) of the 1970s and 1980s in German universities.”ii The conclusion reflected broadly across the various approaches in Engberg’s survey is that the electronic literature teacher must -

10 Gaps for Digital Literature? Serge Bouchardon

Mind the gap! 10 gaps for Digital Literature? Serge Bouchardon ELO Montreal Conference (keynote), 17/08/18: http://www.elo2018.org/ Introduction 2 1. The Field of Digital Literature 3 1.1. Gap No.1 3 Creation: From Building Interfaces to Using Existing Platforms? 1.2. Gap No.2 6 Audience: From a Private to a Mainstream Audience? 1.3. Gap No.3 7 Translation: from Global Digital Cultural Homogeneity to Cultural Specificities? 1.4. Gap No.4 8 The Literary Field: From Literariness to Literary Experience? 2. The Reading Experience 10 2.1. Gap No.5 10 Gestures: From Reading Texts to Interpretation through Gestures? 2.2. Gap No.6 11 Narrative : From Telling a Story to Mixing Fiction with the Reader’s Reality? 2.3. Gap No.7 14 The Digital Subject: From Narrative Identity to Poetic Identity? 3. Teaching and Research 16 3.1. Gap No.8 16 Pedagogy: From Literacy to Digital Literacy? 3.2. Gap No.9 19 Preservation: From a Model of Stored Memory to a Model of Reinvented Memory? 3.3. Gap No.10 23 Research: From an Epistemology of Measure to an Epistemology of Data? Conclusion 25 Bibliography 26 1 Introduction What exactly do we mean by digital literature? This field has existed for over six decades, descending from clearly identified lineages (combinatorial writing and constrained writing, fragmentary writing, sound and visual writing…). The terminology varies, and digital, electronic, and computer-based literature are all commonly used. Yet most critics in the field are in agreement on the distinction between the two principal forms of literature relying on digital media: digitized literature and true digital literature (even if the boundary between the two is sometimes rather blurred, perhaps increasingly so). -

Postscripts Fall 2019

The Jacksonville State University English Department Alumni Newsletter Postscripts Fall 2019 Grand Prismatic Hot Spring in Yellowstone National Park taken by Stephen Kinney & submitted by Jennifer Foster 2-8 JSU’s Adventures Out West 9-12 Hail and Farewell: Dr. Harding Retires 12-14 The Shakespeare Project 15-18 All the World’s a Stage: Spotlight on Emily Duncan 19-20 Miscellany 20 Imagining the Holocaust 21-22 Writers Bowl 23 Writer’s Club 23 Southern Playwrights Competition 23 Sigma Tau Delta 24-31 Postscripts Bios 31 English Department Foundation 32-34 Student Sampler 1 JSU’s Adventures Out West by Jennifer Foster In December of 2017, JSU’s provost and long-time supporter of the American Democracy Project (ADP), Dr. Rebecca Turner, sent out a call for JSU faculty volunteers to attend a week- long seminar, scheduled for May 2018, on the stewardship of public lands in Yellowstone National Park (YNP). I quickly responded with a request to be considered as an attendee because while I had travelled to the park a couple of times, I had never been in the spring, and I had never been to the northern range. My initial justification for going was to experience, yet again, the beauty and diversity of ecosystems and wildlife unique to YNP. I wish I could truthfully write that I had the foresight to envision what would happen over the next year as a result of this trip, but that isn’t the case. I’m still not exactly sure how the ADP’s seminar evolved into a large JSU group returning in 2019 with the potential for subsequent groups to follow, and I have to fight myself not to overly romanticize my experiences. -

The Emergence of Cyber Literature: a Challenge to Teach Literature from Text to Hypertext

Proceedings | “Netizens of the World #NOW: Elevating Critical Thinking through Language and Literature” | ISBN 978-602-50956-4-1 THE EMERGENCE OF CYBER LITERATURE: A CHALLENGE TO TEACH LITERATURE FROM TEXT TO HYPERTEXT Deri Sis Nanda [email protected] Susanto Susanto [email protected] Bandar Lampung University, Indonesia Abstract In a digital era, people live in a cyberspace that they become part of modern society. The information that they have acquired is from the World Wide Web (WWW). This WWW has become an important medium for people in the world to disseminate information. Because of the technology of Web, cyber literature emerges. This study talks about the emergence of cyber literature which changes the way of reading and teaching in various institutions. It becomes a challenge for people who teach literature because they should leave the printed text and move to the digital text as called hypertext. The existence of cyber literature also drives them change their style to analyze and criticize the work of literature. So, it becomes a challenge for them to teach literature from text to hypertext. Keywords: cyber literature, emergence, text, hypertext, cyberspace, challenge, development. Introduction The influence of technology changes all aspects of people’s lives in the world. They become modern society who always get information and do communication in a virtual space. The influence can be seen in work places, homes and teaching institutions. Most of them acquire the information from the World Wide Web (WWW). It is a space for the users to read, write, and access the information with devices connected with the internet. -

Silence and Beauty

SILENCE AND BEAUTY Reflections A companion guide for introspection and discussion on Mako Fujimura’s book and video series CONTENTS Introduction 3 A companion to video 1 Fumi-e 7 A companion to video 2 Outsider vs. Insider 10 A companion to video 3 The Voice of God 14 Through Silence A companion to video 4 The Third Way 17 A companion to video 5 Silence and Beauty 20 Examined A companion to video 6 Silence 23 Discussion guide based on the novel by Shusaku Endo INTRODUCTION A companion to video 1 Born in Boston to Japanese parents, Mako Fujimura became the first nonnative to study in a prestigious school of painting in Japan that dates back to the fifteenth century. Throughout the process of completing Tokyo University of the Art’s doctoral- level lineage program he learned the ancient nihonga technique that relies on natural pigments derived from stone-ground minerals and from cured oyster, clam, and scallop shells. Rather than painting traditional subjects such as kimonos and cherry blossoms, Fujimura applied the nihonga style to his preferred modern medium of abstract expressionism. — from Silence and Beauty: Hidden Faith Born of Suffering Mako Fujimura, in his book Silence and Beauty, vividly reflects on his personal journey into Shusaku Endo’s Silence. By his chapter title of the same name, “A Journey Into Silence,” the curious subtitle reads: Pulverization. 3 Mako goes on to say, I entered the darkly lit exhibit room alone. The studio given to me as a National Scholar was a few blocks away from the Tokyo National Museum at Tokyo University of the Arts. -

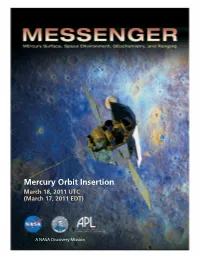

Mercury Orbit Insertion March 18, 2011 UTC (March 17, 2011 EDT)

Mercury Orbit Insertion March 18, 2011 UTC (March 17, 2011 EDT) A NASA Discovery Mission Media Contacts NASA Headquarters Policy/Program Management Dwayne C. Brown (202) 358-1726 [email protected] The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Mission Management, Spacecraft Operations Paulette W. Campbell (240) 228-6792 or (443) 778-6792 [email protected] Carnegie Institution of Washington Principal Investigator Institution Tina McDowell (202) 939-1120 [email protected] Mission Overview Key Spacecraft Characteristics MESSENGER is a scientific investigation . Redundant major systems provide critical backup. of the planet Mercury. Understanding . Passive thermal design utilizing ceramic-cloth Mercury, and the forces that have shaped sunshade requires no high-temperature electronics. it, is fundamental to understanding the . Fixed phased-array antennas replace a deployable terrestrial planets and their evolution. high-gain antenna. The MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space . Custom solar arrays produce power at safe operating ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) temperatures near Mercury. spacecraft will orbit Mercury following three flybys of that planet. The orbital phase will MESSENGER is designed to answer six use the flyby data as an initial guide to broad scientific questions: perform a focused scientific investigation of . Why is Mercury so dense? this enigmatic world. What is the geologic history of Mercury? MESSENGER will investigate key . What is the nature of Mercury’s magnetic field? scientific questions regarding Mercury’s . What is the structure of Mercury’s core? characteristics and environment during . What are the unusual materials at Mercury’s poles? these two complementary mission phases. What volatiles are important at Mercury? Data are provided by an optimized set of miniaturized space instruments and the MESSENGER provides: spacecraft tele commun ications system.