The Impact of China's Anti-Corruption Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018)

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-18-2018 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross- Strait Relations Jing Feng [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Recommended Citation Feng, Jing, "Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 777. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/777 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China’s Cross-Strait Relationship Jing Feng Capstone Project APS 650 Professor Brian Komei Dempster May 15, 2018 2 Abstract Taiwan’s strategic geopolitical position—along with domestic political developments—have put the country in turmoil ever since the post-Chinese civil war. In particular, its antagonistic, cross-strait relationship with China has led to various negative consequences and cast a spotlight on the country on the international diplomatic front for close to over six decades. After the end of the Cold War, the democratization of Taiwan altered her political identity and released a nation-building process that was seemingly irreversible. Taiwan’s nation-building efforts have moved the nation further away from reunification with China. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

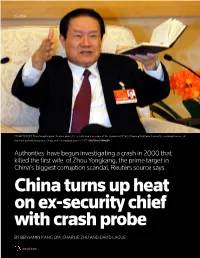

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Business Risk of Crime in China

Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Roderic Broadhurst John Bacon-Shone Brigitte Bouhours Thierry Bouhours assisted by Lee Kingwa ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 3 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Business and the risk of crime in China : the 2005-2006 China international crime against business survey / Roderic Broadhurst ... [et al.]. ISBN: 9781921862533 (pbk.) 9781921862540 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Crime--China--21st century--Costs. Commercial crimes--China--21st century--Costs. Other Authors/Contributors: Broadhurst, Roderic G. Dewey Number: 345.510268 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon; designer unknown, 1993; (Landsberger Collection) International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . vii Lu Jianping Preface . ix Acronyms . xv Introduction . 1 1 . Background . 25 2 . Crime and its Control in China . 43 3 . ICBS Instrument, Methodology and Sample . 79 4 . Common Crimes against Business . 95 5 . Fraud, Bribery, Extortion and Other Crimes against Business . -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Essays in China's Anti-corruption Campaign Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/16g527r2 Author Lu, Xi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Essays in China's Anti-corruption Campaign by Xi Lu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Agricultural and Resource Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Brian D. Wright, Chair Professor David Zilberman Professor Thibault Fally Professor Peter L. Lorentzen Spring 2017 Essays in China's Anti-corruption Campaign Copyright 2017 by Xi Lu 1 Abstract Essays in China's Anti-corruption Campaign by Xi Lu Doctor of Philosophy in Agricultural and Resource Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Brian D. Wright, Chair China's unique system of hiring and promoting talented people within the state, under the supervision of the Communist Party, has been held up as an important institutional factor supporting its remarkably rapid and sustained economic growth. Jointly with Professor Peter L. Lorentzen, we explore this meritocracy argument in the context of Chinese leader Xi Jinping's ongoing anti-corruption campaign. Some question the sincerity of the campaign, arguing that it is nothing but a cover for intra-elite struggle and a purge of Xi's opponents. In the first chapter of my thesis, we use a dataset I have created to identify accused officials and map their connections. Our evidence supports the Party's claim that the crackdown is primarily a sincere effort to cut down on the widespread corruption that was undermining its efforts to develop an effective meritocratic governing system. -

Corruption and Economic Growth in China: an Emirical Analysis Nicholas D'amico John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Senior Honors Projects Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2015 Corruption and Economic Growth in China: An Emirical Analysis Nicholas D'Amico John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation D'Amico, Nicholas, "Corruption and Economic Growth in China: An Emirical Analysis" (2015). Senior Honors Projects. 78. http://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers/78 This Honors Paper/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. D’Amico 1 Introduction China’s rise to a global economic superpower in the last 35 years has been nothing short of extraordinary. Factors that have played a part include China’s liberalization of its financial system, opening up to foreign markets, and massive comparative advantage in labor. An intriguing issue, and the focus of this paper, involves the role that corruption has played in China’s unprecedented economic growth. Corruption is an intriguing issue in part because the literature disagrees on its potential economic impacts. On the one hand, some research finds that corruption is detrimental to economic growth, and this is no different in China (Cole, Elliott, and Zhang 1-32, Bergsten, Freeman, Lardy, and Mitchell 91-105). The elimination of corruption is necessary in order for China’s economic growth to be sustainable in the future. -

The Lions's Share, Act 2. What's Behind China's Anti-Corruption Campaign?

The Lions’s Share, Act 2. What’s Behind China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign? Guilhem Fabre To cite this version: Guilhem Fabre. The Lions’s Share, Act 2. What’s Behind China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign?. 2015. halshs-01143800 HAL Id: halshs-01143800 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01143800 Preprint submitted on 20 Apr 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Séminaire BRICs FMSH - CRBC The Lions’s Share, Act 2. What’s Behind China’s Anti-Corruption Campaign? Guilhem Fabre N°92 | april 2015 As we have seen in a previous working paper ( « The lion’s share : What’s behind China’s economic slowdown ? »), China’s elite have largely benefited from control of state assets and manipulation of the factors market (land, labor and capital) during the first decade of this cen- tury. Along with strong growth and social mobility, the accumulation of wealth has created some of the most flagrant social polarization worldwide, much higher than the official statistics. Instead of taking concrete measures to correct these inequalities, according to the new blueprint of reforms launched by the 3rd Plenum in November 2013, the new direction has focused on a gigantic campaign against corruption. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement October 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 44 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 49 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 56 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 60 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Chapter 2 Beijing's Internal and External Challenges

CHAPTER 2 BEIJING’S INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CHALLENGES Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is facing internal and external challenges as it attempts to maintain power at home and increase its influence abroad. China’s leadership is acutely aware of these challenges and is making a concerted effort to overcome them. • The CCP perceives Western values and democracy as weaken- ing the ideological commitment to China’s socialist system of Party cadres and the broader populace, which the Party views as a fundamental threat to its rule. General Secretary Xi Jin- ping has attempted to restore the CCP’s belief in its founding values to further consolidate control over nearly all of China’s government, economy, and society. His personal ascendancy within the CCP is in contrast to the previous consensus-based model established by his predecessors. Meanwhile, his signature anticorruption campaign has contributed to bureaucratic confu- sion and paralysis while failing to resolve the endemic corrup- tion plaguing China’s governing system. • China’s current economic challenges include slowing econom- ic growth, a struggling private sector, rising debt levels, and a rapidly-aging population. Beijing’s deleveraging campaign has been a major drag on growth and disproportionately affects the private sector. Rather than attempt to energize China’s econo- my through market reforms, the policy emphasis under General Secretary Xi has shifted markedly toward state control. • Beijing views its dependence on foreign intellectual property as undermining its ambition to become a global power and a threat to its technological independence. China has accelerated its efforts to develop advanced technologies to move up the eco- nomic value chain and reduce its dependence on foreign tech- nology, which it views as both a critical economic and security vulnerability.