Looking for the Missing Link in the Evolution of Black Inks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Blitz on Bugs in the Bedding

THE MAGAZINE OF THE INSTITUTE OF CONSERVATION • SEPTEMBER 2011 • ISSUE 36 A blitz on bugs in the bedding Also in this issue PACR news and the new Conservation Register Showcasing intern work in Ireland A 16th century clock WILLARD CONSERVATION EQUIPMENT visit us online at www.willard.co.uk Willard Conservation manufactures and supplies a unique range of conservation tools and equipment, specifically designed for use in the conservation and preservation of works of art and historic cultural media. Our product range provides a premier equipment and technology choice at an affordable price. Visit our website at www.willard.co.uk to see our wide range of conservation equipment and tools and to find out how we may be able to help you with your specific conservation needs. Willard Conservation Limited By Appointment To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Leigh Road, Terminus Industrial Estate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8TS Conservation Equipment Engineers Willard Conservation Ltd, T: +44 (0)1243 776928 E: [email protected] W: www.willard.co.uk Chichester 2 inside SEPTEMBER 2011 Issue 36 It is an autumn of welcomes. 2 NEWS First, welcome to the new version of the Conservation Interesting blogs and Register which went live at the end of August. Do take a look websites , research projects, at it at www.conservationregister.com and help with putting uses for a municipal sculpture right any last minute glitches by filling in the feedback survey and a new bus shelter form. 7 Welcome, too, to the latest batch of Accredited members. 4 PROFESSIONAL UPDATE Becoming accredited and then sustaining your professional Notice of Board Elections and credentials is no walk in the park, so congratulations for the next AGM, PACR updates, completing the first stage and good luck in your future role as training and library news the profession’s exemplars and ambassadors. -

History and Treatment of Works in Iron Gall Ink September 10-14, 2001, 9:30-5:30 Daily Museum Support Center Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education

2001 RELACT Series The History and Treatment of Works in Iron Gall Ink September 10-14, 2001, 9:30-5:30 daily Museum Support Center Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education Instructors: Birgit Reibland, Han Neevel, Julie Biggs, Margaret Cowan Additional Lecturers: Jacque Olin, Elissa O'Loughlin, Rachel-Ray Cleveland, Linda Stiber Morenus, Heather Wanser, Abigail Quandt, Christine Smith, Maria Beydenski, Season Tse, Elmer Eusman, Scott Homolka This 3-day course (offered twice in one week for 2 separate groups of participants) focuses on one of the most corrosive media problems found on documents and works of art on paper. The 2-day workshop and 1 interim day of lectures cover the production of inks from historic recipes; historic drawing and writing techniques; identification, examination and classification of deterioration; and the execution of treatment options, including the use of calcium phytate solution. The interim day of lectures will feature local and international conservators' research into the history and treatment of works with iron gall ink. The course represents the first time iron gall ink has been the primary focus of an international gathering in the United States. Registration deadline for the full course is July 1 or until the course is filled with qualified applicants; for the interim day of lectures only, participants have until August 29 to register. Limit for Interim Day of Lectures: 30 Lunch and handouts provided Cost: $ 75.00 Registration deadline August 29 The 3-day course is fully enrolled. Places still remain for the Interim Day of Lectures. Please contact Mary Studt, [email protected] or 301-238-3700 x149 for further information and application materials. -

Writing About Espionage Secrets

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 2 Number 1 Secrecy and Intelligence Article 7 September 2018 Writing About Espionage Secrets Kristie Macrakis Georgia Tech, Atlanta, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Macrakis, Kristie. 2018. "Writing About Espionage Secrets." Secrecy and Society 2(1). https://doi.org/10.31979/2377-6188.2018.020107 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/ secrecyandsociety/vol2/iss1/7 This Special Issue Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writing About Espionage Secrets Abstract This article describes the author’s experiences researching three books on espionage history in three different countries and on three different topics. The article describes the foreign intelligence arm of the Ministry for State Security; a global history of secret writing from ancient to modern times; and finally, my current project on U.S. intelligence and technology from the Cold War to the War on Terror. The article also discusses the tensions between national security and openness and reflects on the results of this research and its implications for history and for national security. Keywords Central Intelligence Agency, CIA, -

Judging Permanence for Reformatting Projects: Paper and Inks

ConserveO Gram September 1995 Number 19/14 Judging Permanence For Reformatting Projects: Paper And Inks Many permanently valuable NPS documents fibered, high alpha-cellulose cotton and linen such as correspondence, drawings, maps, plans, rags. Early rag papers were strong, stable, and reports were not produced using permanent and durable with relatively few impurities. and durable recording media. When selecting In the mid-17th century, damaging alum paper items for preservation duplication, items sizing was added to control bacteria and marked on the list below with a " - " are at mold growth in paper. By 1680, shorter highest risk and should have special priority for fiber rag papers were being produced due to duplication. Document types marked with a the use of mechanical metal beaters to shred "+" are lower priorities for reformatting as they the rag fibers. By about 1775, damaging tend to be more stable and durable. See chlorine bleaches were added to rag papers Conserve O Gram 19/10, Reformatting for to control the paper color. Acidic alum Preservation and Access: Prioritizing Materials rosin sizing was introduced around 1840 to for Duplication, for a full discussion of how to speed the papermaking process thus leading select materials for duplication. NOTE: Avoid to even shorter-lived papers. Rag papers using materials and processes marked " - " when became less common after the introduction producing new documents. of wood pulp paper around 1850. Compared to rag paper, most wood pulp papers have Paper much poorer chemical chemical and mechanical strength, durability, and stability. All permanently valuable original paper - documents should be produced on lignin-free, Ground or mechanical wood pulp paper: high alpha-cellulose papers with a pH between After 1850, most paper produced was 7.5 and 8.0, specifically those papers meeting machine-made paper with a high proportion the American National Standards Institute of short-fibered and acidic wood pulp. -

The Inky Story of the Dinky Oak Gall

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- ubP lished Research US Geological Survey 2014 The nkyI Story of the Dinky Oak Gall Ken Sulak research biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (Biological Resources), [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Part of the Geology Commons, Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons, Other Earth Sciences Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Sulak, Ken, "The nkI y Story of the Dinky Oak Gall" (2014). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 1066. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/1066 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- ubP lished Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Volume 31: Number 1 > 2014 The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society Palmetto The Inky Story of the Dinky Oak Gall ● A Native Celebration ● The Rebirth of Cape Florida Pea galls on live oak leaves (Quercus virginiana) induced by Belonocnema treatae, a gall wasp. The Inky Story of the Dinky Oak Gall Article and photos by Ken Sulak Spring in North Florida – and all those magnificent live oaks are sporting a bright new flush of green leaves. Last year’s old clothes, those worn out leaves now lie dry and brown on the forest floor. But look closely and you will soon notice that many of those leaves are decorated with rows or clusters of little round woody galls on their underside, like little brown pearls. -

Technical Note on Treatment Options for Iron Gall Ink on Paper with a Focus on Calcium Phytate

Technical Note on Treatment Options for Iron Gall Ink on Paper with a Focus on Calcium Phytate Sherry Guild, Season Tse and Maria Trojan-Bedynski Journal of the Canadian Association for Conservation (J. CAC), Volume 37 © Canadian Association for Conservation, 2012 This article: © Canadian Conservation Institute, 2012. Reproduced with the permission of the Canadian Conservation Institute (http://www.cci-icc.gc.ca/imprtnt-eng.aspx), Department of Canadian Heritage. J.CAC is a peer reviewed journal published annually by the Canadian Association for Conservation of Cultural Property (CAC), 207 Bank Street, Suite 419, Ottawa, ON K2P 2N2, Canada; Tel.: (613) 231-3977; Fax: (613) 231- 4406; E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.cac-accr.ca. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors, and are not necessarily those of the editors or of CAC. Journal de l'Association canadienne pour la conservation et la restauration (J. ACCR), Volume 37 © l'Association canadienne pour la conservation et la restauration, 2012 Cet article : © l’Institut canadien de conservation, 2012. Reproduit avec la permission de l’Institut canadien de conservation (http://www.cci-icc.gc.ca/imprtnt-fra.aspx), Ministère du Patrimoine canadien. Le J.ACCR est un journal révisé par des pairs qui est publié annuellement par l'Association canadienne pour la conservation et la restauration des biens culturels (ACCR), 207, rue Bank, Ottawa (Ontario) K2P 2N2, Canada; Téléphone : (613) 231-3977 ; Télécopieur : (613) 231-4406; Adresse électronique : [email protected]; Site Web : http://www.cac-accr.ca. Les opinions exprimées dans la présente publication sont celles des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de la rédaction ou de l'ACCR. -

Inkwell Stand

Inkwell Stand By Inga Milbauer This antique Victorian inkwell stand with two covered inkwells belonged to Reverend George S. Dodge who was the pastor of the Congregational Church in Boylston from 1902 to 1917. The decorative inkwell stand is made of cast iron, as are the covers of the two glass inkwells. The back of the stand has a Western horseshoe design decorated with a horse head and a spot to rest your writing instrument. It measures about 6x3x5 inches. It was made by the Peck Stow & Wilcox Company. The Peck Stow & Wilcox Company dates back to 1797. Seth Peck of Southington, Connecticut started to manufacture tools and machines to replace the hand tools used by tinsmiths. Several firms succeeded the business and by 1870 the S. Stow Mfg. Co. of Plantsville, Connecticut and the Roys & Wilcox Co. of East Berlin, Connecticut were competitors. In December 1870 these two firms and the Peck, Smith Co. united and established a joint stock company named the Peck, Stow & Wilcox Company. In 1881 the Wilcox, Treadway & Co. of Cleveland, Ohio was acquired by the company. Tinsmiths’ tools and machines were the main products, but other items such as tools for carpenters, machinists and blacksmiths, and a variety of housekeeping products were also made. The company was bought out by Billings & Spencer in 1950. Inkwells made out of stone with round hollows date back to Ancient Egypt. Different materials such as glass, porcelain, animal horns, pewter, silver and other metals would later be used. From the seventeenth century onwards, inkwells became more elaborate and decorative as more people around the world began to use them. -

STEM @ HOME GUIDE: Invisible Ink

STEM @ HOME GUIDE: Invisible Ink • Aim: To write a secret message using lemons • Materials required: Lemon HELPFUL TIPS Water You can use fresh lemons or Small Bowl lemon juice. Q Tips or paint brush White paper Don’t get the paper too wet or it will take much longer to dry. Heat source (bright lightbulb, candle, stovetop) BE CAREFUL AND HAVE AN ADULT HANDLE THE HEAT SOURCE Using a candle or stove will work much faster, but a lightbulb will work as well. • Questions to think about before you start: How can I use a lemon to write a secret message? Why do we need heat? • Instructions: Make sure to perform the experiment as a team (parent and student). Parent: Cut the lemon in half . Student: Squeeze half of the lemon into a bowl or cup and add a small amount of water . Student: Stir the lemon juice and water together . Student: Optional: You can write a decoy message in pen or pencil before you write your secret message. Student: Take your Q tip or brush and dip it into the lemon water and write your secret message on the paper. Parent: Once the paper is dry hold the paper over your chosen heat source to reveal the secret message. Be careful not to hold it to close or it may catch on fire • Extensions Activities: Does it matter which side of the paper you expose to the heat? Try using another acidic substance like orange juice, milk, honey or vinegar to write your messages, notice which substances work better. -

CHG Library Book List

CHG Library Book List (Belgium), M. r. d. a. e. d. h. (1967). Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire, Bruxelles, Musées royaux d'art et dʹhistoire, Parc du Cinquantenaire, 1967. Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire by Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire (Belgium) (1967) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (January, 1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5 by Thomas P.F. Hoving (1968) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1973). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXXI, Number 3. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.), A. B. S. (2002). Persephone. U.S.A/ Cambridge, President and Fellows of Harvard College Puritan Press, Inc. (Ed.), A. D. (2005). From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Hellenic Art in Adversity, 1453-1830. /Benaki Museum. Athens, Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. (Ed.), B. B. R. (2000). Christian VIII: The National Museum: Antiquities, Coins, Medals. Copenhagen, The National Museum of Denmark. (Ed.), J. I. (1999). Interviews with Ali Pacha of Joanina; in the autumn of 1812; with some particulars of Epirus, and the Albanians of the present day (Peter Oluf Brondsted). Athens, The Danish Institute at Athens. (Ed.), K. D. (1988). Antalya Museum. İstanbul, T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Döner Sermaye İşletmeleri Merkez Müdürlüğü/ Ankara. (ed.), M. N. B. (Ocak- Nisan 2010). "Arkeoloji ve sanat. (Journal of Archaeology and Art): Ölümünün 100.Yıldönümünde Osman Hamdi Bey ve Kazıları." Arkeoloji Ve Sanat 133. -

Brazilian Journal of Forensic Sciences, Medical Law and Bioethics 7(3):156-161 (2018)

Brazilian Journal of Forensic Sciences, Medical Law and Bioethics 7(3):156-161 (2018) Brazilian Journal of Forensic Sciences, Medical Law and Bioethics Journal homepage: www.ipebj.com.br/forensicjournal Decipherment of Disappeared Ink: A Case Study Deshpande Hemantini*, Mulani Khudbudin Regional Forensic Science Laboratory, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India-431002 * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The disappeared or invisible inks are fluids used to for secret writing. These types of inks are revealed by heat, chemical reaction and UV light. Disappearing inks are acid base indicators showing different colours at different pH. Writing with this type of ink disappears after about 65 h. These inks could be used for forging the documents such as agreements, cheques, property documents and other important documents. Many destructive and non- destructive methods are available for forensic decipherment of these disappeared writing. In present communication, a simple nondestructive method is applied for decipherment of disappeared signatures on share transfer agreement and other related documents. Keywords: Forensic Science, Disappearing ink. 1. Introduction Basically, ink is a composition of dyes or pigments along with some additives to give desired physical properties. Nowadays, varieties of ink composition are available in the market which consists of various organic, inorganic and synthetic material with various characteristics and properties1,2. Disappearing ink is used as marking system for sports, in dress making industry. It is also used as teaching material to make answer invisible. By using coloring agents, answers become visible. Disappearing inks are also applied in paint industries to locate the area which is not painted. However, these are a great challenge for forensic document examiner as used in forgery or counterfeiting documents. -

Invisible Ink

Excitement in Chemistry Sourav Pal National Chemical Laboratory, Pune- 411008 [email protected] NCL Outreach, 17 January, 2010 http://www.ncl.org.in/tcs/estg/spalhomepage.html NATIONAL CHEMICAL LABORATORY, PUNE, INDIA “Science is organized and systematized knowledge relating to our physical world Observation of phenomena as they occur in nature and their faithful recording As the observations multiplied, regularities were sought and the facts were systematized. Formulation into laws, capable of embracing a number of facts and of summarizing them in succinct form with predictive power, these laws became theory. By comparison with experiments theories can be refined and new principles discovered” . Scientific method or temper Correlation of facts or explanation of qualitative information. Quantification and understanding in terms of laws and objectivity Combination of experiment and theory using the scientific method has led to the development of present science. Chemistry: Study of substances, their properties, structures and transformations. Synthesis of molecules of great complexity Chemistry • Chemistry is the study of matter and interactions between them. • Chemistry and Physics are closely related. ( chemical Physics) • Chemistry tends to focus on the properties of substances and the interactions between different types of matter, involving study of electrons. Physics tends to focus more on the nuclear part of the atom, as well as the subatomic realm. CHEMISTRY MOVES ON TWO WHEELS CURIOSITY UTILITY George Whitesides What Fields of Study Use Chemistry • Chemistry is used in most fields, but it's commonly seen in the sciences and in medicine. Chemists, physicists, biologists, and engineers study chemistry. • Chemistry is the central science. -

Invisible Ink

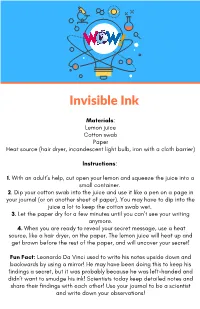

Invisible Ink Materials: Lemon juice Cotton swab Paper Heat source (hair dryer, incandescent light bulb, iron with a cloth barrier) Instructions: 1. With an adult’s help, cut open your lemon and squeeze the juice into a small container. 2. Dip your cotton swab into the juice and use it like a pen on a page in your journal (or on another sheet of paper). You may have to dip into the juice a lot to keep the cotton swab wet. 3. Let the paper dry for a few minutes until you can’t see your writing anymore. 4. When you are ready to reveal your secret message, use a heat source, like a hair dryer, on the paper. The lemon juice will heat up and get brown before the rest of the paper, and will uncover your secret! Fun Fact: Leonardo Da Vinci used to write his notes upside down and backwards by using a mirror! He may have been doing this to keep his findings a secret, but it was probably because he was left-handed and didn’t want to smudge his ink! Scientists today keep detailed notes and share their findings with each other! Use your journal to be a scientist and write down your observations! Tinta Invisible Materiales: Zumo de limón Bastoncillo de algodón Papel Fuente de calor (secador de pelo, bombilla incandescente, plancha con barrera de tela) Instrucciones: 1. Con la ayuda de un grande, abre tu limón y exprime el zumo en un recipiente pequeño. 2. Sumerge el bastoncillo en el zumo y úsalo como si fuera una pluma en una página en su diario (o en otra hoja de papel).