Pinter and the Paranoid Style in English Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fences Study Guide

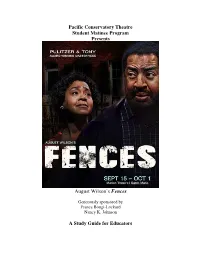

Pacific Conservatory Theatre Student Matinee Program Presents August Wilson’s Fences Generously sponsored by Franca Bongi-Lockard Nancy K. Johnson A Study Guide for Educators Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to PCPA at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. 2. Once seated in the theater, students may go to the bathroom in small groups and with the teacher's permission. Please chaperone younger students. Once the show is over, please remain seated until the House Manager dismisses your school. 3. Please remind your students that we do not permit: - food, gum, drinks, smoking, hats, backpacks or large purses - disruptive talking. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Plays to Read for Furman Theatre Arts Majors

1 PLAYS TO READ FOR FURMAN THEATRE ARTS MAJORS Aeschylus Agamemnon Greek 458 BCE Euripides Medea Greek 431 BCE Sophocles Oedipus Rex Greek 429 BCE Aristophanes Lysistrata Greek 411 BCE Terence The Brothers Roman 160 BCE Kan-ami Matsukaze Japanese c 1300 anonymous Everyman Medieval 1495 Wakefield master The Second Shepherds' Play Medieval c 1500 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Elizabethan 1599 Shakespeare, William Twelfth Night Elizabethan 1601 Marlowe, Christopher Doctor Faustus Jacobean 1604 Jonson, Ben Volpone Jacobean 1606 Webster, John The Duchess of Malfi Jacobean 1612 Calderon, Pedro Life is a Dream Spanish Golden Age 1635 Moliere Tartuffe French Neoclassicism 1664 Wycherley, William The Country Wife Restoration 1675 Racine, Jean Baptiste Phedra French Neoclassicism 1677 Centlivre, Susanna A Bold Stroke for a Wife English 18th century 1717 Goldoni, Carlo The Servant of Two Masters Italian 18th century 1753 Gogol, Nikolai The Inspector General Russian 1842 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House Modern 1879 Strindberg, August Miss Julie Modern 1888 Shaw, George Bernard Mrs. Warren's Profession Modern Irish 1893 Wilde, Oscar The Importance of Being Earnest Modern Irish 1895 Chekhov, Anton The Cherry Orchard Russian 1904 Pirandello, Luigi Six Characters in Search of an Author Italian 20th century 1921 Wilder, Thorton Our Town Modern 1938 Brecht, Bertolt Mother Courage and Her Children Epic Theatre 1939 Rodgers, Richard & Oscar Hammerstein Oklahoma! Musical 1943 Sartre, Jean-Paul No Exit Anti-realism 1944 Williams, Tennessee The Glass Menagerie Modern -

Broadway Guest Artists & High-Profile Key Note Speakers

Broadway Guest Artists & High-Profile Key Note Speakers George Hamilton, Broadway and Film Actor, Broadway Actresses Charlotte D’Amboise & Jasmine Guy speaks at a Chicago Day on Broadway speak at a Chicago Day on Broadway Fashion Designer, Tommy Hilfiger, speaks at a Career Day on Broadway AMY WEINSTEIN PRESIDENT, CEO AND FOUNDER OF STUDENTSLIVE Amy Weinstein has been developing, creating, marketing and producing education programs in partnership with some of the finest Broadway Artists and Creative teams since 1998. A leader and pioneer in curriculum based standards and exciting and educational custom designed workshops and presentations, she has been recognized as a cutting edge and highly effective creative presence within public and private schools nationwide. She has been dedicated to arts and education for the past twenty years. Graduating from New York University with a degree in theater and communication, she began her work early on as a theatrical talent agent and casting director in Hollywood. Due to her expertise and comprehensive focus on education, she was asked to teach acting to at-risk teenagers with Jean Stapleton's foundation, The Academy of Performing and Visual Arts in East Los Angeles. Out of her work with these artistically talented and gifted young people, she co-wrote and directed a musical play entitled Second Chance, which toured as an Equity TYA contract to over 350,000 students in California and surrounding states. National mental health experts recognized the play as an inspirational arts model for crisis intervention, and interpersonal issues amongst teenagers at risk throughout the country. WGBH/PBS was so impressed with the play they commissioned it for adaptation to teleplay in 1996. -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY in the LAKE (1947, 105 Min)

September 22, 2015 (XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY IN THE LAKE (1947, 105 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Directed by Robert Montgomery Written by Steve Fisher (screenplay) based on the novel by Raymond Chandler Produced by George Haight Music by David Snell and Maurice Goldman (uncredited) Cinematography by Paul Vogel Film Editing by Gene Ruggiero Art Direction by E. Preston Ames and Cedric Gibbons Special Effects by A. Arnold Gillespie Robert Montgomery ... Phillip Marlowe Audrey Totter ... Adrienne Fromsett Lloyd Nolan ... Lt. DeGarmot Tom Tully ... Capt. Kane Leon Ames ... Derace Kingsby Jayne Meadows ... Mildred Havelend Pink Horse, 1947 Lady in the Lake, 1945 They Were Expendable, Dick Simmons ... Chris Lavery 1941 Here Comes Mr. Jordan, 1939 Fast and Loose, 1938 Three Morris Ankrum ... Eugene Grayson Loves Has Nancy, 1937 Ever Since Eve, 1937 Night Must Fall, Lila Leeds ... Receptionist 1936 Petticoat Fever, 1935 Biography of a Bachelor Girl, 1934 William Roberts ... Artist Riptide, 1933 Night Flight, 1932 Faithless, 1931 The Man in Kathleen Lockhart ... Mrs. Grayson Possession, 1931 Shipmates, 1930 War Nurse, 1930 Our Blushing Ellay Mort ... Chrystal Kingsby Brides, 1930 The Big House, 1929 Their Own Desire, 1929 Three Eddie Acuff ... Ed, the Coroner (uncredited) Live Ghosts, 1929 The Single Standard. Robert Montgomery (director, actor) (b. May 21, 1904 in Steve Fisher (writer, screenplay) (b. August 29, 1912 in Marine Fishkill Landing, New York—d. September 27, 1981, age 77, in City, Michigan—d. March 27, age 67, in Canoga Park, California) Washington Heights, New York) was nominated for two Academy wrote for 98 various stories for film and television including Awards, once in 1942 for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Here Fantasy Island (TV Series, 11 episodes from 1978 - 1981), 1978 Comes Mr. -

Schedule of Exhibitions and Events

No. 1 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART FOR RELEASE: 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. January 1, I962 TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 HOURS: ADMISSION: Weekdays: 11 am - 6 pm, Thursdays until 10 pm Adults: $1.00 Sundays: 1 pm - 7 pm Children: 25 cents The entire Museum will be open Thursday evenings until 10 p.m. throughout the winter, with concerts, films, lectures and symposia in the auditorium at 8:30. Dinner and light refreshments are available. SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS Note: Full releases on each exhibition are available five days before the opening. Photographs are available on request from Elizabeth Shaw, Publicity Director. JANUARY OPENING -~ ——— 1 *" ' ** Jan. 30 - PHOTOGRAPHS BY HARRY CALLAHAN & ROBERT FRANK, the last of the "Diogenes'' April 1 series initiated by Steichen in 1952. About 100 works by each photogra pher; Callahan's, a retrospective of the past 20 years, Frank's, the contemporary scene in a search for "the vision of hope and despair." Directed by Edward Steichen, assisted by Grace M. Mayer.(Auditorium gall. FUTURE OPENINGS EST Feb. 21 - JEAN DUBUFFET, the first major retrospective in an American museum of April 8 the work of the leading artist to emerge in France since World War II. More than 200 works - paintings, assemblages, drawings and sculpture - dating from the last two decades, borrowed from this country and abroad. Directed by Peter Selz, who has also written a monograph on the artist. To be shown at the Art Institute of Chicago during the spring and the Los Angeles County Museum in the summer of I962. -

Dumb-Belling Her Way to Fame

Paje TWIG Dumb-belling Her Way to Fame The layingl of Suzanne, merry, ing.nuoUi and abounding in whimlical error, have become the talk of the Itudio, Experts in movie behaviorism and worldly willdom haven't been able to de- termine whether her malapropisms are genuine or feigned. She has "a lin.:' but whether it is native clevemell or congenital "dumbne.s" is an unsolved problem. ,......•••...... She couldn't make any sense out of (l dictionary because it wasn't written in complete sentences. way's mental capacity. For ex- Movie Veteran at 19 Years of Age ample, she was handed a dte- tionary and asked if she knew how to use it. She said: By GEORGE SHAFFER Bovard family, founders of th University of Southern Calif 01 "The book I've got at home Hollywood, Cal. nia here. makes sense, but this one isn't ALTHOUGH but 19, .Mary The actress's mother, Mr: even written in complete sen- Belch, former Blooming- I"l.. Hulda Belch, and her brothel tences." ton, Ill., girl, is already a Albert, 18, now make their hom She informed Director Prinz HoI Lyw 0 0 d "trouper." Her with Mary in Hollywood. He that she wanted to be an act- screen career began on a daring father resides in Chicago. Th ress instead of a dancer "be- chance When, three years ago, mother and brother moved rror cause actresses get to sit down the high school sophomore long their Bloomington home whe oftener." distanced Bob Palmer, RKO· Mary came west to take up he Radio studios' casting director, • • • movie career. -

The OCE Lamron, 1957-04-22

Walters Elected ASOCE President for '58 ·Student Council Executive Board THE OCE Named for Year of 1957-.1958 At the counting of the ballots of the ASOCE executive council election, it was revealed that H. T. Walters was elected student body president. AM RON There was much excitement as Lionel Miller, Sherry Ripple, Vol. 34, No. 23 Monday, April 22, 1957 Oregon College of Education j Kay LeFrancq, Bill Benner and Phyllis Seid tallied the 504 ballots - indicating the winners. The 504 balloti represented 73% of the stu dent body. The closest of the races was that of first vice-president in which Jim Beck won by a margin of eight votes. The widest margin was found in the presidential race with a safe surplus of 51 votes in favor of H. T. Walters. The results of the "Joe College" and "Betty Coed" votes will be announced at the Talent Show next Saturday. The following is the official record of the election: ASOCE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL - 1957 - 1958 RESULTS (Number Voting - 504) 1st 2nd tQt. 3rd tot. 4th tot. 5th tot. SECRETARY (*Elected) *Kobayashi, Sue .............. 257 (elected) Sakamoto, Charlotte , .... 232 Discards ........................ 15 2nd VICE-PRESIDENT Babb, Bev 78 10 88 (eliminated) *Bauman, Deanne .............. 86 11 97 29 126 27 151 99 252 Huston, Lynn .................... 89 14 103 10 113 (eliminated) \ Martin, Ron ...................... 92 18 110 23 133 51 184 48 232 Reiber, Dale ...................... 68 (eliminated) White, Carolyn ................ 89 10 99 21 120 32 152 (elim'td) Discards ........................ 2 5 7 5 12 3 15 5 20 Totals ...................... 504 68 504 88 504 113 504 152 504 1st VICE-PRESIDENT I *Beck, Jim ....................... -

THE VISITOR March 24–May 10

PRESS CONTACT: [email protected] // 212-539-8624 THE PUBLIC THEATER ANNOUNCES COMPLETE CASTING FOR WORLD PREMIERE MUSICAL THE VISITOR March 24–May 10 Music by Tom Kitt Lyrics by Brian Yorkey Book by Kwame Kwei-Armah & Brian Yorkey Choreography by Lorin Latarro Directed by Daniel Sullivan Joseph Papp Free Preview Performance Tuesday, March 24 February 13, 2020 – The Public Theater (Artistic Director, Oskar Eustis; Executive Director, Patrick Willingham) announced complete casting today for the world premiere musical THE VISITOR, with music by Pulitzer Prize winner Tom Kitt, lyrics by Pulitzer Prize winner Brian Yorkey, book by Kwame Kwei- Armah and Brian Yorkey, and choreography by Lorin Latarro. Directed by Tony Award winner Daniel Sullivan, this new musical will begin performances in the Newman Theater with a Joseph Papp Free Preview performance on Tuesday, March 24. THE VISITOR will run through Sunday, May 10, with an official press opening on Wednesday, April 15. The complete cast of THE VISITOR features Jacqueline Antaramian (Mouna), Robert Ariza (Ensemble), Anthony Chan (Ensemble), Delius Doherty (Ensemble), C.K. Edwards (Ensemble), Will Erat (Ensemble), Sean Ewing (Swing), Marla Louissaint (Ensemble), Ahmad Maksoud (Ensemble), Dimitri Joseph Moïse (Ensemble), Takafumi Nikaido (Ensemble/Drummer), Bex Odorisio (Ensemble), David Hyde Pierce (Walter), Paul Pontrelli (Ensemble), Lance Roberts (Ensemble), Ari’el Stachel (Tarek), and Stephanie Torns (Swing), with Alysha Deslorieux joining the company as Zainab, replacing the previously announced Joaquina Kalukango, who withdrew due to scheduling conflicts. With heart, humor, and lush new songs, Pulitzer Prize and Tony-winning team Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey with Kwame Kwei-Armah bring their soul-stirring new musical based on the acclaimed independent film, THE VISITOR by Thomas McCarthy, to The Public for its world premiere.