Alou Makes the Catch’ Changes Cubs History, Mostly for the Better

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reign Men Taps Into a Compelling Oral History of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series

Reign Men taps into a compelling oral history of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series. Talking Cubs heads all top CSN Chicago producers need in riveting ‘Reign Men’ By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 23, 2017 Some of the most riveting TV can be a bunch of talking heads. The best example is enjoying multiple airings on CSN Chicago, the first at 9:30 p.m. Monday, March 27. When a one-hour documentary combines Theo Epstein and his Merry Men of Wrigley Field, who can talk as good a game as they play, with the video skills of world-class producers Sarah Lauch and Ryan McGuffey, you have a must-watch production. We all know “what” happened in the Game 7 Cubs victory of the 2016 World Series that turned from potentially the most catastrophic loss in franchise history into its most memorable triumph in just a few minutes in Cleveland. Now, thanks to the sublime re- porting and editing skills of Lauch and McGuffey, we now have the “how” and “why” through the oral history contained in “Reign Men: The Story Behind Game 7 of the 2016 World Series.” Anyone with sense is tired of the endless shots of the 35-and-under bar crowd whooping it up for top sports events. The word here is gratuitous. “Reign Men” largely eschews those images and other “color” shots in favor of telling the story. And what a tale to tell. Lauch and McGuffey, who have a combined 20 sports Emmy Awards in hand for their labors, could have simply done a rehash of what many term the greatest Game 7 in World Series history. -

Baseball History

Christian Brothers Baseball History 1930 - 1959 By James McNamara, Class of 1947 Joseph McNamara, Class of 1983 1 Introductory Note This is an attempt to chronicle the rich and colorful history of baseball played at Christian Brothers High School from the years 1930 to 1959. Much of the pertinent information for such an endeavor exists only in yearbooks or in scrapbooks from long ago. Baseball is a spring sport, and often yearbooks were published before the season’s completion. There are even years where yearbooks where not produced at all, as is the case for the years 1930 to 1947. Prep sports enjoyed widespread coverage in the local papers, especially during the hard years of the Great Depression and World War II. With the aid of old microfilm machines at the City Library, it was possible to resurrect some of those memorable games as told in the pages of the Sacramento Bee and Union newspapers. But perhaps the best mode of research, certainly the most enter- taining, is the actual testimony of the ballplayers themselves. Their recall of events from 50 plus years ago, even down to the most minor of details is simply astonishing. Special thanks to Kathleen Davis, Terri Barbeau, Joe Franzoia, Gil Urbano, Vince Pisani, Billy Rico, Joe Sheehan, and Frank McNamara for opening up their scrapbooks and sharing photographs. This document is by no means a complete or finished account. It is indeed a living document that requires additions, subtractions, and corrections to the ongoing narrative. Respectfully submitted, James McNamara, Class of 1947 Joseph McNamara, Class of 1983 2 1930 s the 1920’s came to a close, The Gaels of Christian Brothers High School A had built a fine tradition of baseball excellence unmatched in the Sacra- mento area. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Chicago Cubs (52-30) Vs. Cincinnati Reds (30-54) July 4, 2016

CHICAGO CUBS (52-30) VS. CINCINNATI REDS (30-54) JULY 4, 2016 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E LOB Reds 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 0 4 9 2 6 Cubs 3 3 0 2 0 2 0 0 X 10 12 1 12 Winning Pitcher: Hendricks (7-6) Losing Pitcher: Reed (0-3) Save: None STARTING PITCHERS GAME INFORMATION Pitcher IP H R ER BB SO WP HR PC/S Left Time of Game: 3:01 Cody Reed (L) 4.0 5 8 4 3 2 0 2 78/42 0-8 First Pitch: 1:22 pm Kyle Hendricks (W) 5.1 4 1 1 1 2 0 0 100/68 8-0, 2 on Temperature: 71 Degrees Courtesy of STATS, Inc. Wind: SE 8 mph HOME RUNS ATTENDANCE INFORMATION Team Batter No. Pitcher Inn. Count Men On Location Today: 41,293 CHI Bryant 24 Reed 2 0-0 1 Left-Center Field Season Total: 1,439,617 CHI Contreras 5 Reed 2 1-1 0 Left Field # of Wrigley Games: 37 (26-11) CHI Russell 9 Smith 6 0-1 1 Left Field Basket Average per Game: 38,909 CIN Cozart 12 Wood 7 0-0 1 Left Field Basket CIN Suarez 15 Wood 7 3-2 0 Left-Center Field CHICAGO CUBS KRIS BRYANT (1-for-1, 2 BB, 3 R, HR, 2 RBI) belted his Major League-tying 24th homer of the season, a two-run shot in the second … he’s batting .455 (20-for-44) with 18 runs scored, nine walks, eight homers and 20 RBI in 11 games against the Reds this year … his eight blasts against the Reds are the most by a single player against any team this season … exited the game in the bottom of the fifth inning with a lower left leg contusion. -

Too Cool—Families Catch the Cool!

2010 SPRING Cool Culture® provides 50,000 underserved families with free, unlimited sponsored by JAQUELINE KENNEDY access to ONASSIS 90 cultural institutionsRESEVOIR - so that parents can provide their children withCENTRAL PARK 80 Hanson Place, Suite 604, Brooklyn, NY 11217 www.coolculture.org educational experiences that will help them succeed in school and life. CENTRAL PARK HARLEM MEER Malky, Simcha, Stanley and Avi Mayerfeld. Fi e tzpa t trick t . Vaness e a Griffi v th and Ys Y abe l Fitzpat FIFTH AVENUE d rick. n a o FIFTH AVENUE i g r e S , a n i t n e g r A Isabella, Sophia and Ethel Zaldaña 108TH ST 107TH ST 106TH ST 103RD ST 105TH ST 102ND ST 104TH ST 101ST ST 100TH ST 99TH ST 98TH ST 97TH ST 96TH ST 95TH ST 94TH ST 93RD ST 92ND ST 91ST ST 90TH ST 89TH ST 88TH ST 87TH ST 86TH ST 85TH ST 84TH ST 83RD ST 82ND ST 81ST ST Felicia and Omaria Williams F e l ic ia a nd he t C C O o o m o a h ri W o To ol— illiams atc l! Families C The Cool Culture community couldn't choose just one. “I really liked came together to Catch the Cool on making stuff and meeting my friend and June 8th at the Museum Mile getting a poster by (artist) Michael Albert,” she said. The siblings – along with Festival! Thousands painted, drew, their sister Ysabel (one), mom Yvette and aunt danced and partied on Fifth Avenue from Vanessa Griffith– participated in art activities 105th Street to 82nd Street, dropping in that included crafting monkey ears at The museums along the way. -

PDF of August 17 Results

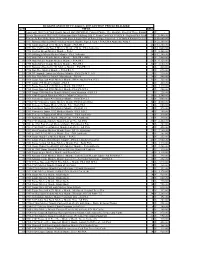

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist 1 Hoyt Wilhelm 2 Alvin Dark 3 Joe Coleman 4 Eddie Waitkus 5 Jim Robertson 6 Pete Suder 7 Gene Baker 8 Warren Hacker 9 Gil McDougald 10 Phil Rizzuto 11 Bill Bruton 12 Andy Pafko 13 Clyde Vollmer 14 Gus Keriazakos 15 Frank Sullivan 16 Jimmy Piersall 17 Del Ennis 18 Stan Lopata 19 Bobby Avila 20 Al Smith 21 Don Hoak 22 Roy Campanella 23 Al Kaline 24 Al Aber 25 Minnie Minoso 26 Virgil Trucks 27 Preston Ward 28 Dick Cole 29 Red Schoendienst 30 Bill Sarni 31 Johnny TemRookie Card 32 Wally Post 33 Nellie Fox 34 Clint Courtney 35 Bill Tuttle 36 Wayne Belardi 37 Pee Wee Reese 38 Early Wynn 39 Bob Darnell 40 Vic Wertz 41 Mel Clark 42 Bob Greenwood 43 Bob Buhl Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Danny O'Connell 45 Tom Umphlett 46 Mickey Vernon 47 Sammy White 48 (a) Milt BollingFrank Bolling on Back 48 (b) Milt BollingMilt Bolling on Back 49 Jim Greengrass 50 Hobie Landrith 51 El Tappe Elvin Tappe on Card 52 Hal Rice 53 Alex Kellner 54 Don Bollweg 55 Cal Abrams 56 Billy Cox 57 Bob Friend 58 Frank Thomas 59 Whitey Ford 60 Enos Slaughter 61 Paul LaPalme 62 Royce Lint 63 Irv Noren 64 Curt Simmons 65 Don ZimmeRookie Card 66 George Shuba 67 Don Larsen 68 Elston HowRookie Card 69 Billy Hunter 70 Lew Burdette 71 Dave Jolly 72 Chet Nichols 73 Eddie Yost 74 Jerry Snyder 75 Brooks LawRookie Card 76 Tom Poholsky 77 Jim McDonald 78 Gil Coan 79 Willy MiranWillie Miranda on Card 80 Lou Limmer 81 Bobby Morgan 82 Lee Walls 83 Max Surkont 84 George Freese 85 Cass Michaels 86 Ted Gray 87 Randy Jackson 88 Steve Bilko 89 Lou -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter to collector and introduction to catalog ........................................................................................ 4 Auction Rules ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Clean Sweep All Sports Affordable Autograph/Memorabilia Auction Day One Wednesday December 11 Lots 1 - 804 Baseball Autographs ..................................................................................................................................... 6-43 Signed Cards ................................................................................................................................................... 6-9 Signed Photos.................................................................................................................................. 11-13, 24-31 Signed Cachets ............................................................................................................................................ 13-15 Signed Documents ..................................................................................................................................... 15-17 Signed 3x5s & Related ................................................................................................................................ 18-21 Signed Yearbooks & Programs ................................................................................................................. 21-23 Single Signed Baseballs ............................................................................................................................ -

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners TACOMA RAINIERS BASEBALL tacomarainiers.com CHENEY STADIUM /TacomaRainiers 2502 S. Tyler Street Tacoma, WA 98405 @RainiersLand Phone: 253.752.7707 tacomarainiers Fax: 253.752.7135 2019 TACOMA RAINIERS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office/Contact Info .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cheney Stadium .....................................................................................................................................................6-9 Coaching Staff ....................................................................................................................................................10-14 2019 Tacoma Rainiers Players ...........................................................................................................................15-76 2018 Season Review ........................................................................................................................................77-106 League Leaders and Final Standings .........................................................................................................78-79 Team Batting/Pitching/Fielding Summary ..................................................................................................80-81 Monthly Batting/Pitching Totals ..................................................................................................................82-85 Situational -

S Slated for Next Week Martin Elected 5B President; Drama Club to Present'the New Constitution Passed Boy Friend' Ln Arts Festival Fred K

FRESNO COLLEGE rys PUBTISHED ASSOCIATED STUDENTS vor. xvll FRESNO, CATIFORNIA, THURSDAY, MAY 16, 1963 NUMBER 2ó FCC Presents s Slated For Next Week Martin Elected 5B President; Drama Club To Present'The New Constitution Passed Boy Friend' ln Arts Festival Fred K. Martin Jr. was elected ¿ùt mid-terms of the Presid'ent By DAVID PACHECO Many of the items on display will ¡ the new AsÊociated Student Bodv and vice president. This rn'as re- The second annual Fresno City be for sale. president in the election held I College tr'ine Arts Festival begins Fine Arts President Roger I duced from the present 2.1-) aveÌL Derryberry saicl that he is mak- last Friday. age. This tloes not change the tonight as "The Boy Friend," F attempt, ing arrangements for five local Other officers are Kathy Mur- 2.5 over¿ll âver¿ùge tha,t is still CC's first musical hall jazz and. folk singing grouPs to phy, vice president; Caroline needetl-by these officers. Also it opens in the college social 8:15 PM. perform during the noon hour at Poind.exter, secretary; L ar rY le¿rves ¿r,t 2.O the averages thart at Krum, Treasurer; Jim Mclauth- renraining council officets rnust "The Boy Friend" will also be the Art-O-Rama. lin, Associated. Mens President; ¡naintain. presented on Saturday night, Derryberry an n o unc e d tho and groups tentatively scheduled to Susan M. Hawthorne, .A.ssociated New representatives at large May 18, and on May 23, 24, 'Womens ¿ùppoâr. They include the ßtS President. -

Open Auditions on July 14Th and 15Th for Bleacher Bums Through South Suburban College PAC Rats Theatre Company

July 14, 2021 –For Immediate Release Contact: Patrick Rush, [email protected], 708-225-5846 www.ssc.edu/category/news Open Auditions on July 14th and 15th for Bleacher Bums through South Suburban College PAC Rats Theatre Company SOUTH HOLLAND, IL– The PAC Rats Theatre Company of South Suburban College will hold open auditions for the comedy Bleacher Bums on July 14th and 15th, beginning at 7:00 p.m. Readings will be held in the Kindig Performing Arts Center on the main campus at 15800 S. State Street in South Holland, Illinois. In the bleachers at Chicago’s Wrigley Field, die-hard Cub fans root for their team. Members of the group include a sun-worshipper, a blind man who follows the game by transistor radio, a professional gambler, a husband and wife, a nerd, and a little kid. Director Paul Braun of Highland, IN, will cast seven men and two women, of all colors and types, ranging in age from 16 to 70 plus. Braun is planning evening rehearsals. The show, collaboratively written by members of the Chicago’s Organic Theater Company from an idea by actor Joe Mantegna, is set to perform during the last two weekends of September. Auditions are open to all community members as well as SSC students. Appointments and prepared audition materials are not necessary. Auditioners will read from scenes, which will be available at the time of auditions. Be prepared to list all conflicts with the rehearsal schedule. “South Suburban College is still concerned for the safety of our students, staff and community members.” said Ellie Shunko, the manager of the Kindig Performing Arts Center. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig