The Hemlock 7.2 (Spring 2014) Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Teacher and the Forest: the Pennsylvania Forestry Association, George Perkins Marsh, and the Origins of Conservation Education

The Teacher and The ForesT: The Pennsylvania ForesTry associaTion, GeorGe Perkins Marsh, and The oriGins oF conservaTion educaTion Peter Linehan ennsylvania was named for its vast forests, which included well-stocked hardwood and softwood stands. This abundant Presource supported a large sawmill industry, provided hemlock bark for the tanning industry, and produced many rotations of small timber for charcoal for an extensive iron-smelting industry. By the 1880s, the condition of Pennsylvania’s forests was indeed grim. In the 1895 report of the legislatively cre- ated Forestry Commission, Dr. Joseph T. Rothrock described a multicounty area in northeast Pennsylvania where 970 square miles had become “waste areas” or “stripped lands.” Rothrock reported furthermore that similar conditions prevailed further west in north-central Pennsylvania.1 In a subsequent report for the newly created Division of Forestry, Rothrock reported that by 1896 nearly 180,000 acres of forest had been destroyed by fire for an estimated loss of $557,000, an immense sum in those days.2 Deforestation was also blamed for contributing to the pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 4, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 16:19:01 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.4_16_Linehan.indd 520 26/09/12 12:51 PM the teacher and the forest number and severity of damaging floods. Rothrock reported that eight hard-hit counties paid more than $665,000 to repair bridges damaged from flooding in the preceding four years.3 At that time, Pennsylvania had few effective methods to encourage forest conservation. -

Jjjn'iwi'li Jmliipii Ill ^ANGLER

JJJn'IWi'li jMlIipii ill ^ANGLER/ Ran a Looks A Bulltrog SEPTEMBER 1936 7 OFFICIAL STATE September, 1936 PUBLICATION ^ANGLER Vol.5 No. 9 C'^IP-^ '" . : - ==«rs> PUBLISHED MONTHLY COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA by the BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS PENNSYLVANIA BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS HI Five cents a copy — 50 cents a year OLIVER M. DEIBLER Commissioner of Fisheries C. R. BULLER 1 1 f Chief Fish Culturist, Bellefonte ALEX P. SWEIGART, Editor 111 South Office Bldg., Harrisburg, Pa. MEMBERS OF BOARD OLIVER M. DEIBLER, Chairman Greensburg iii MILTON L. PEEK Devon NOTE CHARLES A. FRENCH Subscriptions to the PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER Elwood City should be addressed to the Editor. Submit fee either HARRY E. WEBER by check or money order payable to the Common Philipsburg wealth of Pennsylvania. Stamps not acceptable. SAMUEL J. TRUSCOTT Individuals sending cash do so at their own risk. Dalton DAN R. SCHNABEL 111 Johnstown EDGAR W. NICHOLSON PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contribu Philadelphia tions and photos of catches from its readers. Pro KENNETH A. REID per credit will be given to contributors. Connellsville All contributors returned if accompanied by first H. R. STACKHOUSE class postage. Secretary to Board =*KT> IMPORTANT—The Editor should be notified immediately of change in subscriber's address Please give both old and new addresses Permission to reprint will be granted provided proper credit notice is given Vol. 5 No. 9 SEPTEMBER, 1936 *ANGLER7 WHAT IS BEING DONE ABOUT STREAM POLLUTION By GROVER C. LADNER Deputy Attorney General and President, Pennsylvania Federation of Sportsmen PORTSMEN need not be told that stream pollution is a long uphill fight. -

HIGH ALLEGHENY PLATEAU ECOREGIONAL PLAN: FIRST ITERATION Conservation Science Support—Northeast and Caribbean

HIGH ALLEGHENY PLATEAU ECOREGIONAL PLAN: FIRST ITERATION Conservation Science Support—Northeast and Caribbean The High Allegheny Plan is a first iteration, a scientific assessment of the ecoregion. As part of the planning process, other aspects of the plan will be developed in future iterations, along with updates to the ecological assessment itself. These include fuller evaluations of threats to the ecoregion, constraints on conservation activities, and implementation strategies. CSS is now developing a standard template for ecoregional plans, which we have applied to the HAL first iteration draft report, distributed in 2002. Some of the HAL results have been edited or updated for this version. Click on the navigation pane to browse the report sections. What is the purpose of the report template? The purpose of creating a standard template for ecoregional plans in the Northeast is twofold: — to compile concise descriptions of methodologies developed and used for ecoregional assessment in the Northeast. These descriptions are meant to meet the needs of planning team members who need authoritative text to include in future plan documents, of science staff who need to respond to questions of methodology, and of program and state directors looking for material for general audience publications. — to create a modular resource whose pieces can be selected, incorporated in various formats, linked to in other documents, and updated easily. How does the template work? Methods are separated from results in this format, and the bulk of our work has gone into the standard methods sections. We have tried to make each methods section stand alone. Every section includes its own citation on the first page. -

Pennsylvania Forestry Association News You Can Use

December 2019 | #ForestProud Pennsylvania Forestry Association News You Can Use Consider a gift to the Pennsylvania Forestry Association Each year, the Pennsylvania Forestry Association continues to broaden the scope of work completed, further supporting and impacting efforts of conservation of the Commonwealth's natural resources and practices of sustainable forestry. To do so, we rely on dues revenue from membership dollars and generous donations from our members. As a non-profit, we are committed to ensuring that these dollars support the initiatives, mission and vision of the organization. Our quarterly magazine, which is recognized as a leading member benefit, is one of the single largest expenditures each year. We invite you to consider providing a gift to the Pennsylvania Forestry Association this holiday season. You can either donate online by clicking here, or by downloading and sending the form linked below. Download the donation form. PA Tree Farm Update The Science Behind the Effects of RoundUp Use The news and TV commercials have been causing undo alarm about the dangers of using Round-Up (Glyphosate). Glyphosate is one of the major tools in a tree farmers shed and, as Co_chair of the PATF Committee and a retired USDA Forest Service manager, I want to clear up the rhetoric about this issue. Lots of well-executed scientific studies have been done on the use of glyphosate and none of them report a higher risk of cancer, if applied properly as the directions on the label indicate. The US Forest Service has a mandate from Congress under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that is interpreted as requiring the Forest Service to do risk assessment on any pest control chemicals used on public lands. -

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS and ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 Linear Feet)

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS AND ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 linear feet) Paul Allen was a botanist and plantsman of the American tropics. He was student assistant to C. W. Dodge, the Garden's mycologist, and collector for the Missouri Botanical Garden expedition to Panama in 1934. As manager of the Garden's tropical research station in Balboa, Panama, from 1936 to 1939, he actively col- lected plants for the Flora of Panama. He was the representative of the Garden in Central America, 1940-43, and was recruited after the War to write treatments for the Flora of Panama. The photos consist of 1125 negatives and contact prints of plant taxa, including habitat photos, herbarium specimens, and close-ups arranged in alphabetical order by genus and species. A handwritten inventory by the donor in the collection file lists each item including 19 rolls of film of plant communities in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. The collection contains 203 color slides of plants in Panama, other parts of Central America, and North Borneo. Also included are black and white snapshots of Panama, 1937-1944, and specimen photos presented to the Garden's herbarium. Allen's field books and other papers that may give further identification are housed at the Hunt Institute of Botanical Documentation. Copies of certain field notebooks and specimen books are in the herbarium curator correspondence of Robert Woodson, (Collection 1, RG 4/1/1/3). Gift, 1983-1990. ARRANGEMENT: 1) Photographs of Central American plants, no date; 2) Slides, 1947-1959; 3) Black and White photos, 1937-44. -

PRIMITIVE CAMPING in Pennsylvania State Parks and Forests 11/2014

PRIMITIVE CAMPING in Pennsylvania State Parks and Forests 11/2014 What is Primitive Camping? Primitive camping is a simplistic style of camping. Campers hike, pedal or paddle to reach a location and spend the night without the presence of developed facilities. This primitive camping experience takes place off the beaten path, where piped water, restrooms and other amenities are not provided. You pack in all you need, exchanging a few conveniences for the solitude found in the back country setting. Fresh air, fewer people and out-of-the-way natural landscapes are some of the benefits of primitive camping. Once off the beaten path, however, additional advantages begin to surface such as a deeper awareness and greater appreciation of the outdoor world around you. Primitive camping also builds outdoor skills and fosters a gratifying sense of self-sufficiency. Where to Camp Pennsylvania has 2.2 million acres of state forest land with 2,500 miles of trails and 5,132 miles of Camping at rivers and streams winding through it. Hiking, biking and multi-use trails traverse most state forest districts and six districts have designated water trails that transect state forest land. Forest Districts State parks are not open to primitive camping. However, with the exception of William Penn State Forest, all state forest districts are open to this activity. Camping is not permitted in designated STATE FOREST DISTRICTS: natural areas or at vistas, trail heads, picnic areas and areas that are posted closed to camping. Bald Eagle State Forest (570) 922-3344 Contact a forest district office for specific information, maps and Camping Permits (if needed). -

FALL FOLIAGE REPORT October 1 – October 7, 2020

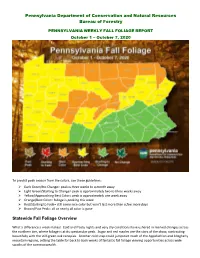

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Bureau of Forestry PENNSYLVANIA WEEKLY FALL FOLIAGE REPORT October 1 – October 7, 2020 TIOGA CAMERON BRADFORD To predict peak season from the colors, use these guidelines: ➢ Dark Green/No Change= peak is three weeks to a month away ➢ Light Green/Starting to Change= peak is approximately two to three weeks away ➢ Yellow/Approaching Best Color= peak is approximately one week away ➢ Orange/Best Color= foliage is peaking this week ➢ Red/Starting to Fade= still some nice color but won’t last more than a few more days ➢ Brown/Past Peak= all or nearly all color is gone Statewide Fall Foliage Overview What a difference a week makes! Cold and frosty nights and very dry conditions have ushered in marked changes across the northern tier, where foliage is at its spectacular peak. Sugar and red maples are the stars of the show, contrasting beautifully with the still-green oak canopies. Another cold snap could jumpstart much of the Appalachian and Allegheny mountain regions, setting the table for back to back weeks of fantastic fall foliage viewing opportunities across wide swaths of the commonwealth. Northwestern Region The district manager in Cornplanter State Forest District (Warren, Erie counties) reports that cooler nights have spurred fall colors in northwest Pennsylvania. Many oaks are still quite green, but maples (sugar and red) are displaying brilliant colors. Aspen, hickory, and birch are continuing to color the landscape with warm yellow hues. Route 6 to Chapman State Park is a recommended fall foliage corridor in Warren County. Exciting fall color can be found at Chapman State Park. -

VEN-03: Venturing Activities (Period 3, March 6, 2004) Hudson Valley Councils University of Scouting Walter Godshall Jeremy J

VEN-03: Venturing Activities (Period 3, March 6, 2004) Hudson Valley Councils University of Scouting Walter Godshall Jeremy J. Kuhar 162 North Main Street 457 South Main Road Mountaintop, PA 18707 Mountaintop, PA 18707 (H) 570.474.6968 (H) 570.678.7554 [email protected] [email protected] 1. Official National Boy Scout Literature Here’s Venturing Venturing Leader Manual Passport to High Adventure Troop Program Features Venturer Handbook Ranger Guidebook Quest Handbook Discovering Adventure Scouting Magazine Boy’s Life 2. Climbing Gyms Wilkes-Barre Rocks (570.824.7633, www.wbcg.net) nd o 102 –104 (2 Floor) South Main Street, Wilkes-Barre, PA 18701 Cathedral Rock & Roll (610.311.8822) st o 226 South 1 Street, Lehighton, PA 18701 3. Skiing Montage Mountain Scout Nights o Tuesday –Sean (570.676.3337), Reservations by 9 PM Mondays o Thursday –Felix (570.678.5589), Reservations by 9 PM Tuesdays 4. West Point Sports Tickets (1.877.TIX.ARMY, www.goARMYsports.com) Lake Fredrick Camping (845.938.3601) Protestant Chapel (845.938.2308) Catholic Chapel (845.938.3721) 5. Annapolis Walking Tours (410.263.6933, www.navyonline.com, Fax: 410.263.7682) Sports Tickets (1.800.US.4.NAVY) Chuck Roydhouse (Volunteer, 410.268.0979) Naval Station Camping (410.293.9200) Marilyn Barry (Scout Liaison, 410.293.9200) Naval Station Meals (410.293.9117) 6. Minsi Trails Council, BSA (610.264.8551, www.minsitrails.com) P.O. Box 20624, Lehigh Valley, PA 18001-0624 8 Minsi Trails Historic Hikes 7. York Adams Area Council, BSA (717.843.0901, www.yaac-bsa.org) 2139 White Street, York, PA 17404 Gettysburg Historic Trail York City Historic Trail 8. -

University of Georgia Historic Contexts

University of Georgia Historic Contexts Historic Contexts Associated with the History of the University of Georgia Historic contexts are patterns, events, or trends in history that occurred within the time period for which a historic property is being assessed or evaluated. Historic contexts help to clarify the importance of a historic property by allowing it to be compared with other places that can be tied to the context. In the case of the University of Georgia, there are multiple historic contexts associated with the historic properties that are the focus of this study due to the complexity, age, and variety of resources involved. Historic contexts pertaining Figure 13. Wadham to the University of Georgia can be tied to trends in campus planning and design, College, Oxford. (Source: architectural styles, vernacular practices, educational practices and programs, Turner, 14) scientific research efforts, government programs, and archeology, among other topics. These trends can be seen as occurring at a local, state, or even national level. The section that follows presents an overview of several historic contexts identified in association with the UGA historic properties considered in detail later in this document, identified through research, documentation, and assessment efforts. The historic contexts presented below suggest the connections between physical development of UGA historic properties and themes, policies, Figure 14. Gonville and practices, and legislation occurring at a broader level, and list one or more Caius College, Cambridge. specific examples of the historic resources that pertain to each context. (Source: Turner, 13) Historic context information is used as a tool by preservation planners to assess if a property illustrates a specific historic context, how it illustrates that context, and if it possesses the physical features necessary to convey the aspects of history with which it is associated. -

Pennsylvania Happy Places

( ) Finding Outside Insights from the People Who Know Pennsylvania’s State Parks and Forests DCNR.PA.gov 1845 Market Street | Suite 202 Camp Hill, PA 17011 717.236.7644 PAParksandForests.org Penn’s Woods is full of the kinds of places that make people happy. At the Pennsylvania Parks and Forests Foundation we discover this each year when we announce our annual Parks and Forests Through the Seasons photo contest and marvel as your breath-taking entries roll in. And we hear it every day when we talk to the hard-working men and women who earn their daily bread in one of the hundreds of different occupations throughout the parks and forests system. We see the pride they take in their work—and the joy they experience in being outside every day in the places we all love. On the occasion of this 2018 Giving Tuesday, we are delighted to share some of their favorite places. Maybe one of them will become your happy place as well! Visit DCNR.PA.gov for the state park or forest mentioned in this booklet. Drop us a line at [email protected] or visit our Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/PennsylvaniaParksAndForestsFoundation) and let us know what you find Out There. #PAParks&ForestsHappyPlace I’m drawn to rock outcroppings, hence my attraction to several hiking opportunities in the Michaux State Forest. Sunset Rocks Trail (https://www.purplelizard.com/blogs/news/ camp-michaux-and-sunset-rocks-history-vistas-and-more-in-michaux- state-forest), a spur to the Appalachian Trail, rewards the intrepid hiker with amazing views along a rocky spine. -

The STC 50Th Anniversary

Fall/Winter 2017 The STC 50th Anniversary By Wanda Shirk A five-mile hike on a perfect October afternoon preceded The Susquehannock Trail Club (STC) is now an official the evening program. Eight hikers-- Wayne Baumann, quinquagenarian! Five decades ago, the Constitution of Bob Bernhardy, Pat Childs, Mike Knowlton, Janet Long, the club was approved unanimously by 19 charter mem- Ginny Musser, Valorie Patillo, and Wanda Shirk—left the bers on October 18, 1967. Fifty years later to the day, on lodge at 2 PM hiking up the Billy Brown Trail, across the Wednesday, October 18, 2017, current club members Ridge Trail segment of the STS. The hikers returned to gathered at the same location to commemorate the club’s the lodge by 4:30 PM via the Wil and Betty Ahn Trail. founding, and to celebrate five decades of maintaining the Back at the lodge, four other members were busily en- Susquehannock Trail System (STS) and its associated link gaged. Helen Bernhardy created a photo board, Penny trails and crossover trails. Weinhold decorated the tables and dining area, Curt Fifty-eight members attended the celebration at the Sus- Weinhold set up a 14-minute slide show which ran contin- quehannock Lodge, including 53 who packed the dining uously on a 28-inch computer screen throughout the even- room to enjoy excellent prime rib, salmon, or stuffed pork ing, and Lois Morey displayed the club’s array of maps, chops, and four more members who prepared and served guidebooks, patches, shirts, and jackets, along with some the meal—and washed the dishes! Valorie Patillo, Chuck historical materials. -

Susquehanna Greenway & Trail Authority Case Study, August 2014

Susquehanna Greenway & Trail Authority Case Study August 2014 Susquehanna Greenway Partnership Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Trail Organization Types ............................................................................................................................... 3 Advantages and Disadvantages of Trail Ownership Structures .................................................................. 21 Trail Maintenance ....................................................................................................................................... 23 Potential Cost‐Sharing Options ................................................................................................................... 25 Potential Sources and Uses ......................................................................................................................... 27 Economic Benefits ....................................................................................................................................... 32 Two‐County, Three‐County, and Five‐County Draft Budget Scenarios ...................................................... 38 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................... 54 Attachment 1 .............................................................................................................................................