Ontarians on the Move Local Intelligence Report - Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Even More Land Available for Homes and Jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe

March 9, 2017 An update on the total land supply: Even more land available for homes and jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe For more information, contact: Marcy Burchfield Executive Director [email protected] 416-972-9199 ext. 1 Neptis | 1 An update on the total land supply: Even more land available for homes and jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe This is the third in a series of Briefs on the land supply for future urban development designated by municipalities across the Greater Golden Horseshoe to accommodate growth to 2031. This Brief sums up the supply of land in (a) the Designated Greenfield Area (DGA), (b) unbuilt areas within Undelineated Built-up Areas (UBUAs), (c) land added through boundary changes to Barrie and Brantford and (d) Amendment 1 to the Growth Plan. Altogether, the supply of unbuilt land for housing and employment planned until 2031 and beyond is 125,600 hectares. How much land is available for development in the Greater Golden Horseshoe? Determining how much land has been set aside to accommodate future housing and employment across the Greater Golden Horseshoe is a fluid process, because land supply data are not fixed once and for all. Ontario Municipal Board decisions, amendments to local official plans, and boundary adjustments constantly alter the numbers. In the first phase of analysis in 2013, Neptis researchers focused on estimating the extent of the “Designated Greenfield Area” (DGA).1 This was land set aside by municipalities in land budgeting exercises to accommodate the population and employment targets allocated by the Province for the period 2006–2031 in the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. -

225 Henry Street Bldg. 3 Brantford ∙ Ontario

2400 CORNWALL ROAD · OAKVILLE,ONTARIO 225 HENRY STREET BLDG. 3 BRANTFORD ∙ ONTARIO AVAILABLE FOR LEASE HENRY STREET BUILDING 3 WAYNE GRETZKY PARKWAY 52,450 SQ. FT. INDUSTRIAL BUILDING KYLE HANNA* MITCHELL BLAINE* LUKE SLABCZYNSKI* Executive Vice President Senior Vice President Sales Assocaite 416 798 6255 519 340 2309 519 340 2328 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] *Sales Representative 225 HENRY STREET BUILDING 3 // BRANTFORD,ONTARIO PROPERTY SPECIFICATIONS OVER-SIZED TRENCH NEW LED DRIVE-IN DRAIN IN LIGHTING DOORS PLACE LOCATION Wayne Gretzky Parkway & Henry Street SIZE 52,450 Sq. Ft. ASKING RATE $5.95 per Sq. Ft. Net T.M.I (2020) $2.48 POSSESSION October 1, 2020 SHIPPING 1 Truck Level Door, 5 Drive-in Doors ZONING M2 (Outside Storage Permitted) CLICK HERE TO VIEW DETAILED ZONING INFO POWER 600 Volts, 800 Amps Multiple clear heights (High bay: 45’ Low bay: 21’) 2 x 10 Ton cranes, 5 x 1 Ton jib hoist cranes Fully sprinklered COMMENTS Surrounded by numerous retail and restaurant amenities Centre ice location for employment, retail and logistics 2.5 km to Highway 403 225 HENRY STREET BUILDING 3 // BRANTFORD,ONTARIO PHOTOS 225 HENRY STREET BUILDING 3 // BRANTFORD,ONTARIO LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS LOCATION Brantford is centrally located for logistics providers and manufacturers as it is in proximity to: . • Multiple US borders • 3 major markets (Toronto, Detroit, and Buffalo) • Internationally connected railways • Major 400 Series highways (403 and 401) • Three international airports (Toronto Pearson, SITE Hamilton and London) and one local domestic airport (Brantford) Brantford is a one-day drive away from 160 million customers and 60% of all manufacturers in Canada and the US. -

Hamilton to Brantford Rail Trail

Thanks to Our Donors Who Helped Build the Trails TheThe Hamilton-Brantford-CambridgeHamilton-Brantford-Cambridge LinkageLinkage ofof TrailsTrails The trails are provided free for public use, but the cost to acquire the land and build the four trails approached $1.5 million. The funds were provided P by generous donations from the following corporations, individuals and like-minded foundations. In 1993, the City of Brantford commenced its Gordon Glaves Memorial Pathway A major trail system now links the cities of Hamilton, Station Masters Honour Roll along the scenic Grand River. Brantford and Cambridge. These 80 kms of trail form a u SC Johnson and Son, Limited major component in the southern Ontario loop of the u Canadian General-Tower Trans Canada Trail System. u Trans Canada Trail Foundation When opened in 1994 by the Grand River Conservation Authority, u The Jean Rich Foundation the Cambridge to Paris Rail Trail was one of the first abandoned rail lines u Redland Quarries to be converted for recreational trail use in southern Ontario. u TCG Materials u Brant Waterways Foundation P u Province of Ontario In 1996, the Hamilton to Brantford Rail Trail was completed by the Hamilton P & Grand River Conservation Authorities and became Canada's first fully developed, Kilometer Club entirely off-road interurban trail. u Brantford Jaycees u CAA South Central Ontario ! u Canada Trust - Friends of the Environment Foundation In October of 1998 these three trails were joined by the SC Johnson Trail, u Ciba-Geigy through the generosity of SC Johnson and Son Limited of Brantford, to form a u Dofasco Inc. -

Brantford Community Overview

COMMUNITY OVERVIEW 2021 Don’t keep forever on the public road, going only where others have gone. Leave the beaten track occasionally and dive into the woods. You will be certain to find something you have never seen before. Of course, it will be a little thing, but do not ignore it. One discovery will lead to another, and before you know it, you will have something worth thinking about to occupy your mind, and really big discoveries are the result of thought. Alexander Graham Bell Scientist, Inventor, Engineer, and Innovator Alexander Graham Bell Sculpture Bell Telephone Company, Brantford 2 GREETINGS FROM BRANTFORD MAYOR KEVIN DAVIS On behalf of Brantford City Council and the citizens of our community, I am pleased to extend a warm welcome from beautiful Brantford, Ontario. Situated in southwestern Ontario, overlooking the scenic Grand River, Brantford offers the amenities of a large urban centre while maintaining the charms of small town living, making it the ideal location to raise a family or grow a business. It is recognized as a diverse, burgeoning, and successful community that has been identified by MoneySense Magazine as one of Canada’s Top Cities to buy real estate and by Site Selection Magazine as one of the Best Canadian Cities to Invest. As a community with a rich history, it was here that Alexander Graham Bell conceived the idea for the telephone and placed the first long distance telephone call which revolutionized the way we communicate. Nearly 150 years later, knowledge and innovation remain an important part of our culture. Partnerships with Wilfrid Laurier University and Conestoga College have created a vibrant post-secondary presence in our community. -

Annual Report 2019

Newcomer Tour of Norfolk County Student Start Up Program participants Tourism & Economic Development Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Business Incentives & Supports ...................................................................................... 5 Investment Attraction ..................................................................................................... 11 Collaborative Projects ................................................................................................... 14 Marketing & Promotion .................................................................................................. 20 Strategy, Measurement & Success ............................................................................... 31 Performance Measurement ........................................................................................... 32 Advisory Boards ............................................................................................................ 33 Appendix ....................................................................................................................... 35 Staff Team ..................................................................................................................... 40 Prepared by: Norfolk County Tourism & Economic Development Department 185 Robinson Street, Suite 200 Simcoe ON N3Y 5L6 Phone: 519-426-9497 Email: [email protected] www.norfolkbusiness.ca -

ITZ Loblaw Native Plant Store List 2021

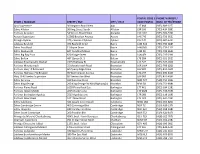

POSTAL CODE / PHONE NUMBER / STORE / MAGASIN STREET / RUE CITY / VILLE CODE POSTAL NUM. DE TÉLÉPHONE Ajax Superstore 30 Kingston Road West Ajax L1T 4K8 (905) 683-2272 Zehrs Alliston 30 King Street South Alliston L9R 1H6 (705) 434-9391 Fortinos Ancaster 54 Wilson Street West Ancaster L9G 1N2 (905) 304-5740 Aurora Superstore 15900 Bayview Avenue Aurora L4G 7Y3 (905) 726-9532 Provigo Aylmer 375, chemin d'Aylmer Aylmer J9H 1A5 (819) 682-4433 Loblaws Bayfield 472 Bayfield Street Barrie L4M 5A2 (705) 735-6689 Zehrs Essa Road 11 Bryne Drive Barrie L4N 8V8 (705) 733-1119 Zehrs Duckworth 607 Cundles Rd East Barrie L4M 0J7 (705) 722-3636 Zehrs Big Bay Point 620 Yonge Street Barrie L4N 4E6 (705) 735-2390 Zehrs Bolton 487 Queen St. S Bolton L7E 2B4 (905) 951-9555 Loblaws Bowmanville Market 2375 Highway #2 Bowmanville L1C 5A3 (905) 623-2600 Fortinos Mountainash 55 Mountainash Road Brampton L6R 1W4 (905) 793-8200 Fortinos Hwy 10 & Bovaird 60 Quarry Edge Drive Brampton L6V 4K2 (905) 453-3600 Fortinos Highway 7 & Brisdale 35 Worthington Avenue Brampton L7A 2Y7 (905) 495-8108 Hwy 10 & Steeles Superstore 85 Steeles Ave West Brampton L6Y 0B5 (905) 451-4999 Zehrs Fairview 410 Fairview Drive Brantford N3R 7V7 (519) 754-4932 Zehrs King George 290 King George Rd Nth/Highway24 Brantford N3R 5L8 (519) 751-8988 Fortinos Plains Road 1059 Plains Road East Burlington L7T 4K1 (905) 634-1591 Fortinos Upper Middle 2025 Guelph Line Burlington L7P 4M8 (905) 336-6566 Fortinos Burlington Appleby 2515 Appleby Line Burlington L7R 0B6 (905) 319-1690 Fortinos New Street 5111 New Street Burlington L7L 1V2 (905) 631-7227 Zehrs Caledonia 322 Argyle Street South Caledonia N3W 1K8 (905) 765-8207 Zehrs Cambridge Centre 400 Conestoga Blvd Cambridge N1R 7L7 (519) 620-1376 Zehrs Hespeler 180 Holiday Inn Drive Cambridge N3C 3Z4 (519) 658-4689 Zehrs South Cambridge 200 Franklin Blvd Cambridge N1R 5S2 (519) 624-8170 Provigo Le Marché Charlesbourg 4545, boul. -

2019 Election: Seat Clusters June to September Survey Results

2019 Election: Seat Clusters June to September Survey Results August 2019 2 Overview In Canada, we count seats, not vote. Just like in American Presidential elections, you can win the popular vote and lose the election. In fact, that happened to Justin Trudeau’s father in 1979. The general way analysts address that is to look at seats by region. However, seats in the same region can move differently. This release tries to get closer to reality in the seat-by-seat contest. Our analysis combines two projects: • An analysis of federal election districts (which we call “seats”) that groups them into 14 clusters based on which parties are most competitive in those seats. Given the shifting dynamics of Canada’s party system, we have relied on only the results of the past two elections. However, to assess where the parties stand in these 14 seat clusters, we need a lot of data. • A merge of the most recent three national surveys that include federal votes, creating a unweighted total of 7,555 respondents and a weighted total of 4,900. In each of our surveys, we collect postal codes. That allows us to create a riding variable for almost all our respondents and to group their responses by the riding they are in. The deck below shows the output from the analysis. The key finding is that, with the NDP in the doldrums, the Liberals are in a strong position coming into the race. Not only have they cemented their hold on last elections core seats, they may be able to gain seats to offsets the losses they will likely experience in the Toronto and Vancouver suburbs and Atlantic Canada. -

Heritage Designation Report: Reasons for Heritage Designation

HERITAGE DESIGNATION REPORT: REASONS FOR HERITAGE DESIGNATION Peterborough Normal School / Teachers College Peterborough Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee January, 2004 Heritage Designation Status Sheet Street Address: 100 Benson Avenue Roll Number: 050080185000000 PIN Number: 281160081 Short Legal Description: Blk D, Pl 101, Lt. 14, Lts. 16-18, Pl. 71, Pt. 1, ECR, Pt 1, RR, 45R1146 Name of Owner(s): Kawartha Pine Ridge District Public School Board Owner’s Mailing Address: Education Centre, 1994 Fisher Drive, Peterborough, Ontario, K9J 7A1. Owner’s Concurrence: yes / no Designation Application Note: Heritage designation included as condition of rezoning by Planning Division. PACAC Application Review Date: October 2002 On-Site Evaluation Date: January 2003. Evaluation Category: A Evaluators: Jim Leonard, Basia Baklinski, Michelle Townsend. Heritage Type: Built Heritage – buildings Built Heritage - interiors Designation Type: Ontario Heritage Act - Part IV Designation Brief Completion Date: February 2003. PACAC Application Approval Date: March 2003. Comments: -The modern addition attached to the south east of the heritage structure, is not to included in the scope and content of the heritage designation with the exception that vertical additions to the addition are subject to heritage review for their impact on the original building. "The short statement of the reason for the designation, including a description of the heritage attributes (below) along with all other components of the Heritage Designation Report constitute the "Reasons for the Designation" required under the Ontario Heritage Act. The Heritage Designation Report is available for viewing in the City Clerk's office during regular business hours." SHORT STATEMENT OF THE REASONS FOR THE DESIGNATION The Peterborough Normal School and surrounding grounds are both architecturally and historically significant. -

In This Issue Tony Storey ’71 Association Co-President’S Message

SEPTEMBER 2003 VOLUME 34, NO.3 TRENT is published three times a year in June, September and February, by the Trent University Alumni Association. Unsigned comments reflect the opinion of the editor only. Trent University Alumni Association, Langton House, Traill College, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, K9J 7B8; call 705-748-1399 or 1-800-267-5774 fax 705-748-1785 e-mail: [email protected] web: www.trentu.ca/alumni EDITOR Liz Fleming ’77 EDITORIAL BOARD Martin Boyne ’86 Marilyn Burns ’00 Jan Carter ’87 Kathleen Easson ’78 Alexandria Morgan Thom ’95 Tania Pattison ’84 Dale Rodger ’77 In This Issue Tony Storey ’71 Association Co-president’s Message . 2 GRAPHIC DESIGN Trent University Design Office University President’s Page . 3 PRINTING AND BINDING Ricter Web Printing Ltd., Brantford Editorial . 4 TRENT UNIVERSITY ALUMNI New VP Academic Susan Clark . 5 ASSOCIATION COUNCIL HONORARY PRESIDENT Alumni Association Honours Students . 6 T.H.B. Symons HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENT Professor David Page Wins Symons Teaching Award . 9 John E. Leishman PRESIDENT Distinguished Researcher Professor John Topic . 10 Rod Cumming ’87 / Maureen Brand ’89 PAST PRESIDENT Vivienne Hall ’86 Profile . 11 Cheryl Davies ’68 VICE-PRESIDENT To Preserve and Protect: Professor Tom Hutchinson . 12 Adam Guzkowski ’95 Reunion Weekend Schedule / Head of the Trent Regatta . centrespread SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT Denis Desjardins ’76 Annual Donor Report . centre insert COUNCILLORS Jan Carter ’87 Georgina Galloway ’91 Chapter Images . 17 Susan Underhill ’87 Lenaee Dupuis ’91 Rock ‘N’ Roll Never Forgets: Bruce Scott ’78 . 18 Mark Gelinas ’89 Iain MacFarlane ’95 Alumni Geography Panel . 20 Jennifer Mercer ‘91 Holly Morrison ’95 Sunshine Sketches . -

Court File No. CV-19-614593-00CL

Court File No. CV-19-614593-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) B E T W E E N: CORNER FLAG LLC Applicant – and – ERWIN HYMER GROUP NORTH AMERICA, INC. Respondent APPLICATION UNDER section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. B-3, as amended, and under section 101 of the Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43 MOTION RECORD OF ALVAREZ & MARSAL CANADA INC., IN ITS CAPACITY AS COURT-APPOINTED RECEIVER AND MANAGER OF ERWIN HYMER GROUP NORTH AMERICA, INC. (Motion for Approval of Sales Process) March 20, 2019 OSLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT LLP 100 King Street West 1 First Canadian Place Suite 6200, P.O. Box 50 Toronto, ON M5X 1B8 Tracy C. Sandler (LSO# 32443N) Tel: 416.862.5890 Jeremy Dacks (LSO# 41851R) Tel: 416.862.4923 Fax: 416.862.6666 Counsel for the Receiver – 2 – TO: THE SERVICE LIST AND TO: THE SUPPLEMENTAL SERVICE LIST Court File No. CV-19-614593-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST BETWEEN: CORNER FLAG LLC Applicant – and – ERWIN HYMER GROUP NORTH AMERICA, INC. Respondents SERVICE LIST (as at March 20, 2019) PARTY CONTACT BLAKE, CASSELS & GRAYDON LLP Pamela L.J. Huff Commerce Court West Tel: 416.863.2958 199 Bay Street, Suite 4600 Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M5L 1A9 Linc Rogers Tel: 416.863.4168 Fax: 416.863.2653 Email: [email protected] Counsel to the Applicant Aryo Shalviri Tel: 416.863.2962 Email: [email protected] Vanja Ginic Tel: 416.863.3278 Email: [email protected] Caitlin McIntyre Tel: 416.863.4174 Email: [email protected] [2] ALVAREZ & MARSAL CANADA INC. -

It Takes a Community to Raise a Child …

United Way 417 Bagot Street Kingston, ON K7K 3C1 (613) 542-2674 www.uway.kingston.on.ca Success By 6 It takes a community to raise a child … A position paper on priorities to help all children in Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox & Addington succeed for life. October 2005 Success by 6 is a United Way coordinated initiative ensuring all children succeed for life 2005, United Way serving KFL&A. All rights reserved. Consulting support provided by 8020info Inc. Success By 6 Position Paper -- 2005 Page 2 of 44 Success By 6 Priority Paper Contents Introduction .............................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary .............................................................................. 5 The Issues As We See Them: Early Learning and Early Childhood Development Opportunities ...... 10 Parenting Skills .................................................................................... 15 Housing and Homelessness Issues ....................................................... 18 Impacts of Poverty ............................................................................... 23 Success By 6 Initiatives ........................................................................ 24 Appendices: Program level Action - Parent Education ............................................ 29 Support for Those at Risk of Losing Housing ..................................... 30 Nine-Point Plan to Give Children a Great Start ................................... 32 Key Informants and Project Participants -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc.