Sexual Morality and Homosexuality in Keralam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Selected Works from Contemporary Malayalam Dalit Poetry Pambirikunnu, V

NavaJyoti, International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research Volume 1, Issue 1, August 2016 Resisting Discriminations: An Analysis of Selected works from Contemporary Malayalam Dalit Poetry Reshma K 1 Assistant Professor, Dept. of English, St. Aloysius College, Elthuruth, India ABSTRACT Dalit Sahitya has a voice of anguish and anger. It protests against social injustice, inequality, cruelty and economic exploitation based on caste and class. The primary motive of Dalit literature, especially poetry, is the liberation of Dalits. This paper focuses on contemporary Dalit poets in Malayalam, Raghavan Atholi, S. Joseph and G. Sashi Madhuraveli, who use their poetry to resist, in a variety of ways their continuing marginalization and discrimination. The poems are a bitter comment on predicament of the Dalits who still live in poverty, hunger, the problems of their colour, race, social status and their names. Keywords: Dalit poetry, resistance, contemporary Malayalam poetry, contemporary Dalit literature Dalit is described as members of scheduled castes and tribes, neo-Buddhists, the working people, landless and poor peasants, women and all those who are exploited politically, economically and in the name of religion (Omvedt 72). B. R. Ambedkar was one of the first leaders who strived for these counter hegemonic groups. He was the first Dalit to obtain a college education in India. All his struggles helped Dalits to come forward. He raised his voice to eradicate untouchability, caste discrimination, non-class type oppressions and women oppressions. All these ‘Ambedkarite’ thoughts formed a hope for the oppressed classes. These counter hegemonic groups resist through literature. Sentiments, hankers and the struggles of the suppressed is portrayed in Dalit literature. -

Kavi Vallathol: the Preserver of Art and Literature

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2019; 5(1): 33-34 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2019; 5(1): 33-34 Mah¡kavi Vallathol: The preserver of art and literature © 2019 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com Received: 09-11-2018 Saraswathi Devi V Accepted: 14-12-2018 Saraswathi Devi V The life, literary and cultural activities of Vallathol Narayana Menon (1878-1958) form a Research Scholar, Dept. of distinct chapter in story of the evaluation of literature and culture in Kerala. Vallathol appeared Sanskrit Sahitya, SSUS, Kalady, on the literary science at a time when Modern Malayalam Poetry was in its infancy. Sanskrit Kerala, India norms in literary composition controlled the literary field, and poetry in Malayalam was only a shadow of what poetry in Sanskrit was. Himself nurtured in the Sanskrit tradition which his early compositions in the Sanskrit form. The poet in company with his two illustrious compeers Ullur and A¿an. Soon made Malayalam poetry with his well known lyrical piece in [1] Dravidian metre a thing of the Kerala Soil . Poetry in Malayalam soon ceased to be a Kerala off shoot of Sanskrit literature and developed with a new secular content and native idiom and [2] form . Vallathol entered to the world of literature through singing Sanskrit Muktakas. He has also written a few works in Sanskrit such as Mat¤viyoga in 21 verses, P¡rvatip¡d¡dike¿astava, K¤snastava and Tapatisamvara¸a. Triy¡ma and Saml¡papura written in collaboration with [3] Vell¡na¿¿ery V¡sunni Mussat . Vallathol was a prodigious writer and author of over eighty works of which ‘Citrayogam’ a mah¡k¡vya, Sahitya Manjari in 10 volumes. -

K. Satchidanandan

1 K. SATCHIDANANDAN Bio-data: Highlights Date of Birth : 28 May 1946 Place of birth : Pulloot, Trichur Dt., Kerala Academic Qualifications M.A. (English) Maharajas College, Ernakulam, Kerala Ph.D. (English) on Post-Structuralist Literary Theory, University of Calic Posts held Consultant, Ministry of Human Resource, Govt. of India( 2006-2007) Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1996-2006) Editor (English), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1992-96) Professor, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1979-92) Lecturer, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1970-79) Lecturer, K.K.T.M. College, Pullut, Trichur (Dt.), Kerala (1967-70) Present Address 7-C, Neethi Apartments, Plot No.84, I.P. Extension, Delhi 110 092 Phone :011- 22246240 (Res.), 09868232794 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Other important positions held 1. Member, Faculty of Languages, Calicut University (1987-1993) 2. Member, Post-Graduate Board of Studies, University of Kerala (1987-1990) 3. Resource Person, Faculty Improvement Programme, University of Calicut, M.G. University, Kottayam, Ambedkar University, Aurangabad, Kerala University, Trivandrum, Lucknow University and Delhi University (1990-2004) 4. Jury Member, Kerala Govt. Film Award, 1990. 5. Member, Language Advisory Board (Malayalam), Sahitya Akademi (1988-92) 6. Member, Malayalam Advisory Board, National Book Trust (1996- ) 7. Jury Member, Kabir Samman, M.P. Govt. (1990, 1994, 1996) 8. Executive Member, Progressive Writers’ & Artists Association, Kerala (1990-92) 9. Founder Member, Forum for Secular Culture, Kerala 10. Co-ordinator, Indian Writers’ Delegation to the Festival of India in China, 1994. 11. Co-ordinator, Kavita-93, All India Poets’ Meet, New Delhi. 12. Adviser, ‘Vagarth’ Poetry Centre, Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal. -

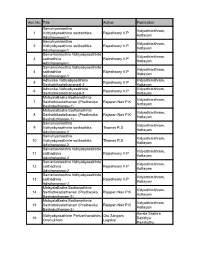

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No. 2 World History Association Denis Gainty Editor [email protected] Editor’s Note From the Executive Director 1 Letter from the President 2 Special Section: The World and The Sea Introduction: The Sea in World History 4 Michael Laver (Rochester Institute of Technology) From World War to World Law: Elisabeth Mann Borgese and the Law of the Sea 5 Richard Samuel Deese (Boston University) The Spanish Empire and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: Imperial Highways in a Polycentric Monarchy 9 Eva Maria Mehl (University of North Carolina Wilmington) Restoring Seas 14 Malcolm Campbell (University of Auckland) Ship Symbolism in the ‘Arabic Cosmopolis’: Reading Kunjayin Musliyar’s “Kappapattu” in 18th Century Malabar 17 Shaheen Kelachan Thodika (Jawaharlal Nehru University) The Panopticon Comes Full Circle? 25 Sarah Schneewind (University of California San Diego) Book Review 29 Abeer Saha (University of Virginia) practical ideas for the classroom; she intro- duces her course on French colonialism in Domesticating the “Queen of Haiti, Algeria, and Vietnam, and explains how Beans”: How Old Regime France aseemingly esoteric topic like the French empirecan appear profoundly relevant to stu- Learned to Love Coffee* dents in Southern California. Michael G. Vann’sessay turns our attention to the twenti- Julia Landweber eth century and to Indochina. He argues that Montclair State University both French historians and world historians would benefit from agreater attention to Many goods which students today think of Vietnamese history,and that this history is an as quintessentially European or “Western” ideal means for teaching students about cru- began commercial life in Africa and Asia. -

Living with Wood to the Participants and the General Public

REDISCOVERING WOOD: THE KEY TO A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE ART AND JOY OF WOOD BANGALORE, INDIA 19 OCTOBER – 22 OCTOBER 2011 PROCEEDINGS PART 1- CONFERENCE OVERVIEW The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107598-2 (print) E-ISBN 978-92-5-107599-9 (PDF) © FAO 2013 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence- request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

Book Publishing in Malayalam the Beginnings

REPORT OF THE MRP TITLED BOOK PUBLISHING IN MALAYALAM THE BEGINNINGS DR BABU CHERIAN DEPARTMENT OF MALAYALAM CMS COLLEGE KOTTAYAM KERALA NO. F. MRP (H)-602/ 08-09/KLMG OO2/ UGC-SWRO/ DT. 30 MARCH 09 CONTENTS Chapter 1 An Introduction to Printing and Book-Publishing Chapter 2 The beginning of Printing in Malayalam that led to Book-Publishing Chapter 3 Malayalam Book Publishing and the first Malayalam Book Published in Kerala Chapter 4 Conclusion Chapter 1 An Introduction to Printing and Book-Publishing Printing is the technology that has recorded the history of all that has happened in the world from the past to the present. Yet, regarding the history of printing, especially the history of the very early days of the technology, not much is known. The invention of printing is a landmark in the history of the World’s civilization, not merely of book- publishing or the dissemination of knowledge. “Printing is the art and technology of recreating, on paper or fabric or on any other surface, pictures or words. Though a variety of printed objects are commonplace in modern times, the principal function of printing is the dissemination of thought and knowledge. Printed words and pictures have become an integral and important part of schools, libraries, education of individuals, intellectual growth and the popular news media” (Encyclopaedia Americana–Printing’). Though there were books when printing was unknown, the world then was the world of the illiterate societies, unable to read or write. “The greatest factor that was instrumental in making Europe civilized, was printing. If Asia and Africa are to see the light and achieve progress as Europe did, at one time or other, it will be, to a great extent, probably through printing”. -

Annual Report 2016-17 Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University

THUNCHATH EZHUTHACHAN MALAYALAM UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 THUNCHATH EZHUTHACHAN MALAYALAM UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS 1. Vice Chancellor’s note 2. Aims and objectives 3. Milestones 4. ‘Akhsaram’ Campus 5. Academic activities 6. Library 7. Student’s welfare, hostels 8. Activities with social commitment 9. International co-operation., Gundert Chair 10. Projects 11. 11. Publications 12. Administration 13. Appendix Editor: Dr. P.B.Lalkar English Translation Team Prof. Madhu Eravankara ( Co-ordinator) Dr. M. Vijayalakshmy, Dr. A.P Sreeraj, Dr. Jainy Varghese, Sri K.S Hakeem Design & Lay-out : Lijeesh M.T. Printing : K.B.P.S. Kakkanad, Kochi P R E FA C E Justice (Retd.) P Sathasivam Prof. C Ravindranath K Jayakumar Chancellor Pro Chancellor Vice Chancellor It is with great pleasure that I am presenting the Annual Report of Malayalam University up to March 31, 2017. The university started functioning in 2012 and the admission formalities of the first batch of students were completed in August 2013. Initially we started with 5 M.A courses. When we look back in 2017, it is worthy to note that the university has achieved tremendous growth both in infrastructure and academic level. Within this short span of time, we could start 10 M.A. Courses and Research Programmes. The first two batches of M.A and one batch of M.Phil students are out. Amenities like Library, Studio and Theatre claims self sufficiency. 28 permanent teachers were also appointed. The year 2016-17 witnessed so many important developments. The new library- research block and Heritage Museum, were opened. The year was marked with variety of academic activities and visit of several dignitaries. -

Roll No Regn No Name F Name Sub1 Sub2 Sub3 Sub4 Sub5 Result 1424452 01-Da-670 Ashish Sharma Narinder Kumar En42 051 Hi41 051

ROLL_NO REGN_NO NAME F_NAME SUB1 SUB2 SUB3 SUB4 SUB5 RESULT 1424452 01-DA-670 ASHISH SHARMA NARINDER KUMAR EN42 051 HI41 051 EP41 051 PA41 051 0413 1447466 02-DMK-231 PARAMJIT KAUR NACHHATTAR SINGH EN42 064 HI41 064 HR41 064 HS41 064 EVS ABSF 0506 1426844 02-NS-1489 RAJ KUMAR JEET RAM CANCEL 1444614 02-PC-26113 SUNITA JANGRA SUBHASH CHANDER EN42 055 HI41 055 ES41 055 SO41 055 EVS ABSF 0434 1465465 03-AGA-137 SUNITA RANI GURMEET SINGH EN42 000F HI41 000F ES41 000F HR41 000F FAIL 1462583 03-PC-2322 KAMLESH BAJRANG LAL EN42 000F HI41 000F ES41 000F HR41 000F FAIL 1435242 04-PC-41376 SANDEEP KUMAR NIRMAL SINGH EN42 041 HI41 041 HR41 041 PS41 041 0328 1424204 04-SDA-1047 PARVESH KUMAR RAGHUBIR SARAN EN42 050 HI41 048 HR41 048 PS41 038 RL-LOW 1457132 04-SDN-293 KIRAN SHARMA RAMAKANT SHARMA EN42 057 HI41 057 PS41 057 SO41 057 0457 1450784 05-PCD-24474 SURENDER KUMAR PALA RAM EN42 000F HI41 000F HR41 000F PS41 000F FAIL 1460014 05-PCD-30637 ANITA VIRBHAN EN42 000F HI41 000F EP41 000F SO41 000F FAIL 1426004 06-DE-18250 NAVEEN KUMAR RAJINDER KUMAR EN42 049 HI41 049 HR41 049 PS41 049 0391 1450536 06-IGK-159 PINKI RANI RAM CHANDER EN42 000F HI41 000F HR41 000F PS41 000F RL-LOW 1426601 06-KN-413 SANDEEP KUMAR INDER SINGH EN42 000F HI41 000F ES41 000F EC41 000F RL-LOW 1438388 06-PCD-26686 BALINDER BALJEET SINGH EN42 039 HI41 039 HR41 039 PS41 039 0316 1438695 07-GCN-497 INDERJEET KAUR TARA CHAND RLA 1448453 07-PCD-18073 RAJBIR SINGH RAM KALA EN42 037 HI41 037 PS41 037 PA41 037 0310 1466033 07-PCD-47180 KUSUM RANI JAI PAL EN42 043 HI41 043 PS41 043 SO41 -

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Kerala

Interview List For Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Kerala Area Of Practice Enrollment S.No. Name Category Appl.Date File No. Father Name Address Applied For No. Nadukkandy House, Puduppanam Manoj Kumar N-11013/5838/2018- Lt.Sh.N.K.Kunhi K/50/1997 1 Gen 04.05.12 Vatakara Po.Vatakara, P.K. NC raman Dt.31.08.97 Kozhikode Distt.Kerala- Mathiyamkallingal M.K. House, Vazhakkad 09.12.11/07.0 N-11013/5839/2018- K/1350/200 2 Muhammedali Gen Malappuram M.K.C.Moideen Po., Malappuram 1.12 NC 3 Dt.20.12.03 Noushad Distt.Kerala- 673640 Mangattu (H), Valiyajarm Edavetty K/254/2000 Muhammed N-11013/5840/2018- 3 Obc 16.03.12 Thodupuzha Ibrahim.M.A Po, Thodupuzha, Dt.05.03.200 Abbas M.I. NC Iddukki Kerala- 0 685588 Parathur House N-11013/5841/2018- K/765/1999 4 Jaison P.A. Gen 11.04.12 Thrissur Distt. P.V .Antony Parannur Choondal NC Dt.05.04.99 Post Kerala-680502 Flat No.5822 Bilathikulam K.P. N-11013/5842/2018- K/518/2002 5 Obc 31.03.12 Kozhikode Dt. Chathu Housing Colony, Kunhiraman NC Dt.25.11.02 Eranhippalam.Po.Ko zhikode Kerala Kashmi Nivas, Edodi 19.11.11/03.0 N-11013/5843/2018- T.Kunhirama Vatakara Kozhikode K/769/1994 6 L. Jyothikumar Gen Vatakara 5.12 NC Kurup Distt. Kerala- Dt.17.07.94 673101 Kovilakam, Karuvattumkuzhy, Kareelakulangara N-11013/5844/2018- K/1098/199 7 Jeeva Kumar S. Obc 11.05.12 Allapuzha Distt. -

On VISIT VISA Expiring on 25.12.2018 VALID U.A.E MANUAL DRIVING LICENSE

CURRICULUM VITAE SHEREEF. P Abu Dhabi - U.A.E. Mobile: 00971 54 498 1767 E-mail: [email protected] On VISIT VISA Expiring on 25.12.2018 VALID U.A.E MANUAL DRIVING LICENSE PROFILE A dedicated, responsible and trustworthy person. Team Player, Goal oriented, Self-Motivated and Proved resilience and delivery under pressure OBJECTIVE I am seeking a position which will allow me to apply and enhance my skills of being an AutoCAD Specialist. In addition, I am eager to contribute my knowledge and hard work towards the success of your company and to the growth of the fast-developing field. ACADEMIC PROFILE Course Institute Diploma Draughtsman Course in Civil Engineering Govt. ITC Shoranur, Kerala – India Diploma AutoCAD Training Course CADD Centre Thrissur, Kerala – India Diploma 3DS MAX Training Course CADD Centre Thrissur, Kerala – India Diploma REVIT Architecture Training Course CADD Centre Pattambi, Kerala - India SKILLS Specialized in 3ds Max and Rivit Architecture. ○ Interior & Exterior designing ○ Food malls, Hotels, Villas, Flats, Hospitals, Houses, Walk through Etc. ○ Prepare scene files created in Autodesk Revit for export to 3ds Max. ○ Link the Revit FBX to 3ds Max, carry out test renders, and make required adjustments. ○ Add a Sky Portal to improve the interior daylight illumination of an enclosed structure. ○ Edit the linked scene in Revit and see the results in 3ds Max. ○ Use the Scene Explorer to organize objects created in Revit. ○ Edit properties of Revit objects in 3ds Max Auto CADD ○ Plan, Elevation, Section, 2D, 3D Etc. DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ○ Experience in AutoCAD Operation in Engineering and Construction. ○ Ability to review Architectural & Structural drawings & produce detailed drawings for construction from basic design.