A Special Transmission Outside the Scriptures - Edited Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’S Mentality

International Conference of Electrical, Automation and Mechanical Engineering (EAME 2015) The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’s Mentality X.H. Li School of literature and Journalism Shandong University Jinan China Abstract—In order to study the influence of Buddhism, most of A. Sukhavati: Maitreya and MiTuo the temples and document in china were investigated. The results Hui Yuan and Daolin Zhi also have faith in Sukhavati. indicated that Buddhism developed rapidly in Southern dynasty. Sukhavati is the world where Buddha live. Since there are Along with the translation of Buddhist scriptures, there were lots many Buddha, there are also kinds of Sukhavati. In Southern of theories about Buddhism at that time. The most popular Dynasty the most prevalent is maitreya pure land and MiTuo Buddhist theories were Prajna, Sukhavati and Nirvana. All those theories have important influence on Nan dynasty’s literati, pure land. especially on their mentality. They were quite different from The advocacy of maitreya pure land is Daolin Zhi while literati of former dynasties: their attitude toward death, work Hui Yuan is the supporter of MiTuo pure land. Hui Yuan’s and nature are more broad-minded. All those factors are MiTuo pure land wins for its simple practice and beautiful displayed in their poems. story. According to < Amitabha Sutra>, Sukhavati is a perfect world with wonderful flowers and music, decorated by all Keyword-the evolvement of buddhism; southern dynasty; kinds of jewelry. And it is so easy for every one to enter this literati’s mentality paradise only by chanting Amitabha’s name for seven days[2] . -

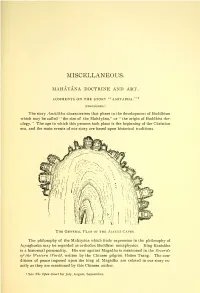

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

Gandharan Origin of the Amida Buddha Image

Ancient Punjab – Volume 4, 2016-2017 1 GANDHARAN ORIGIN OF THE AMIDA BUDDHA IMAGE Katsumi Tanabe ABSTRACT The most famous Buddha of Mahāyāna Pure Land Buddhism is the Amida (Amitabha/Amitayus) Buddha that has been worshipped as great savior Buddha especially by Japanese Pure Land Buddhists (Jyodoshu and Jyodoshinshu schools). Quite different from other Mahāyāna celestial and non-historical Buddhas, the Amida Buddha has exceptionally two names or epithets: Amitābha alias Amitāyus. Amitābha means in Sanskrit ‘Infinite light’ while Amitāyus ‘Infinite life’. One of the problems concerning the Amida Buddha is why only this Buddha has two names or epithets. This anomaly is, as we shall see below, very important for solving the origin of the Amida Buddha. Keywords: Amida, Śākyamuni, Buddha, Mahāyāna, Buddhist, Gandhara, In Japan there remain many old paintings of the Amida Triad or Trinity: the Amida Buddha flanked by the two bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta (Fig.1). The function of Avalokiteśvara is compassion while that of Mahāsthāmaprāpta is wisdom. Both of them help the Amida Buddha to save the lives of sentient beings. Therefore, most of such paintings as the Amida Triad feature their visiting a dying Buddhist and attempting to carry the soul of the dead to the AmidaParadise (Sukhāvatī) (cf. Tangut paintings of 12-13 centuries CE from Khara-khoto, The State Hermitage Museum 2008: 324-327, pls. 221-224). Thus, the Amida Buddha and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas became quite popular among Japanese Buddhists and paintings. However, the origin of this Triad and also the Amida Buddha himself is not clarified as yet in spite of many previous studies dedicated to the Amida Buddha, the Amida Triad, and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas (Higuchi 1950; Huntington 1980; Brough 1982; Quagliotti 1996; Salomon/Schopen 2002; Harrison/Lutczanits 2012; Miyaji 2008; Rhi 2003, 2006). -

Avalokiteśvara and Brahmā's Entreaty

Avalokiteśvara and Brahmā’s Entreaty Akira Saito Preamble As is well known, Avalokiteśvara is a bodhisattva representative of Mahāyāna Buddhism, and beliefs in Avalokiteśvara have flourished wherever Buddhism, especially Mahāyāna Buddhism, spread in Asia. Partly because the characteristic of assuming various forms to save people in distress was attributed to Avalokiteśvara, there evolved six, seven, and thirty-three forms of Avalokiteśvara, who also amalgamated with earth goddesses such as Niangniang 娘娘, and in Japan pilgrimages to sites sacred to Avalokiteśvara have been long established among the general populace, typical of which is the pilgrimage to thirty-three temples in the Kansai region (Saigoku sanjūsansho 西國三十三所). There exists much prior research on Avalokiteśvara, who was accepted in various forms in many regions to which Buddhism spread, and on his iconography, concrete representation, and cult. But on the other hand it is also true that there remains much that is puzzling about the name “Avalokiteśvara” and its meaning, origins, and background. In the following, having first provided a critical overview of recent relevant research, I wish to reconsider the meaning and background of his original name (avalokita-īśvara, -svara, -smara, etc.) in relation to the story of Brahmā’s entreaty, a perspective that has been largely missing in past research. 1. Recent Research on Avalokiteśvara’s Original Name Among studies of Avalokiteśvara in recent years, worthy of particular note are those by Tanaka (2010),1 who discusses in detail -

Buddhist Histories

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 25 Number 1-2 2002 Buddhist Histories Richard SALOMON and Gregory SCHOPEN On an Alleged Reference to Amitabha in a KharoÒ†hi Inscription on a Gandharian Relief .................................................................... 3 Jinhua CHEN Sarira and Scepter. Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics 33 Justin T. MCDANIEL Transformative History. Nihon Ryoiki and Jinakalamalipakara∞am 151 Joseph WALSER Nagarjuna and the Ratnavali. New Ways to Date an Old Philosopher................................................................................ 209 Cristina A. SCHERRER-SCHAUB Enacting Words. A Diplomatic Analysis of the Imperial Decrees (bkas bcad) and their Application in the sGra sbyor bam po gnis pa Tradition....................................................................................... 263 Notes on the Contributors................................................................. 341 ON AN ALLEGED REFERENCE TO AMITABHA IN A KHARO∑™HI INSCRIPTION ON A GANDHARAN RELIEF RICHARD SALOMON AND GREGORY SCHOPEN 1. Background: Previous study and publication of the inscription This article concerns an inscription in KharoÒ†hi script and Gandhari language on the pedestal of a Gandharan relief sculpture which has been interpreted as referring to Amitabha and Avalokitesvara, and thus as hav- ing an important bearing on the issue of the origins of the Mahayana. The sculpture in question (fig. 1) has had a rather complicated history. According to Brough (1982: 65), it was first seen in Taxila in August 1961 by Professor Charles Kieffer, from whom Brough obtained the photograph on which his edition of the inscription was based. Brough reported that “[o]n his [Kieffer’s] return to Taxila a month later, the sculpture had dis- appeared, and no information about its whereabouts was forthcoming.” Later on, however, it resurfaced as part of the collection of Dr. -

The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra (2Nd Edition)

TheThe PrajnaPrajna ParamitaParamita HeartHeart SutraSutra Translated by Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary by Grand Master T'an Hsu English Translation by Ven. Master Lok To Second Edition 2000 HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese By Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary By Grand Master T’an Hsu Translated Into English By Venerable Dharma Master Lok To Edited by K’un Li, Shih and Dr. Frank G. French Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada New York – San Francisco – Toronto 2000 First published 1995 Second Edition 2000 Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada Dharma Master Lok To, Director 2611 Davidson Ave. Bronx, New York 10468 (USA) Tel. (718) 584-0621 2 Other Works by the Committee: 1. The Buddhist Liturgy 2. The Sutra of Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha’s Fundamental Vows 3. The Dharma of Mind Transmission 4. The Practice of Bodhisattva Dharma 5. An Exhortation to Be Alert to the Dharma 6. A Composition Urging the Generation of the Bodhi Mind 7. Practice and Attain Sudden Enlightenment 8. Pure Land Buddhism: Dialogues with Ancient Masters 9. Pure-Land Zen, Zen Pure-Land 10. Pure Land of the Patriarchs 11. Horizontal Escape: Pure Land Buddhism in Theory & Practice. 12. Mind Transmission Seals 13. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra 14. Pure Land, Pure Mind 15. Bouddhisme, Sagesse et Foi 16. Entering the Tao of Sudden Enlightenment 17. The Direct Approach to Buddhadharma 18. -

Diamond Sutra) 『菩薩於法,應無所住,行於布施

Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas Sponsored By Pure Land Center & Buddhist LiBrary 1120 E. Ogden Avenue, Suite 108 Naperville, IL 60563 http://www.amitabhalibrary.org Tel: (630) 428-9941; Fax: (630) 428-9961 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 1 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic One : The Basics èBuddhism is an education, not a religion or a philosophy n It teaches us how to recover our wisdom and regain our Buddha nature n It teaches us how to solve our proBlems through wisdom – an art of living èThe Law of Causality governs everything in the universe èAll sentient Beings possess the same Buddha nature n Our Buddha nature is temporarily lost due to delusion n Our lost Buddha nature can be recovered only via cultivation èKarma refers to an action and its retriBution under the Law of Causality n Good and bad karmas do not offset each other – prevailing ones occur first n Karmas, good or Bad, accumulate over time and do not disappear n When many Bad karmic retriButions come together, they form disasters èCultivation means to stop planting Bad seeds and nurturing Bad conditions, and to, instead, plant good seeds and nurture good conditions Last updated Nov. 2016 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 2 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic Two : The Three Refuges and the Four Reliance -

The Heart of Prajnaparamita

The Heart of the Prajna Paramita Sutra http://www.io.com/~snewton/zen/heartsut.html Portland Zen Community Primary Zen Texts The Wider Zen Sangha Books to Read Random Thoughts Search these Texts Zen Buddhist Texts Home The free seeing Bodhisattva of compassion, while in profound contemplation of Prajna Paramita, beheld five skandhas as empty in their being and thus crossed over all sufferings. O-oh Sariputra, what is seen does not differ from what is empty, nor does what is empty differ from what is seen; what is seen is empty, what is empty is seen. It is the same for sense perception, imagination, mental function and judgement. O-oh Sariputra, all the empty forms of these dharmas neither come to be nor pass away and are not created or annihilated, not impure or pure, and cannot be increased or decreased. Since in emptiness nothing can be seen, there is no perception, imagination, mental function or judgement. There is no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body or consciousness. Nor are there sights, sounds, odors, tastes, objects or dharmas. There is no visual world, world of consciousness or other world. There is no ignorance or extinction of ignorance and so forth down to no aging and death and also no extinction of aging and death. There is neither suffering, causation, annihilation nor path. There is no knowing or unknowing. Since nothing can be known, Bodhisattvas rely upon Prajna Paramita and so their minds are unhindered. Because there is no hindrance, no fear exists and they are far from inverted and illusory thought and thereby attain nirvana. -

The Ocean of Zen

TThhee OOcceeaann ooff ZZeenn 金金 風風 禪禪 宗宗 Page 1 Page 2 The Ocean of Zen A Practice Guide to Korean Sŏn Buddhism Paul W. Lynch, JDPSN First Edition Before Thought Publications Los Angeles and Mumbai 2006 Page 3 BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS 3939 LONG BEACH BLVD LONG BEACH, CA 90807 http://www.goldenwindzen.org/books ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2008 PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page 4 Epigraph Twenty-Seventh Case of the Blue Cliff Record A monk asked Chán Master Yúnmén Wényǎn1, “How is it when the tree withers and the leaves fall?” Master Yúnmén replied; “Body exposed in the golden wind.” Page 5 Page 6 Dedication This book is dedicated to our Dharma Brother – Glenn Horiuchi, pŏpsa–nim – who left this earthly realm before finishing the great work of life and death. We are confident that he will return to finish the great work he started. Page 7 Page 8 Foreword There is considerable underlying confusion for Western Zen students who begin to study the tremendous wealth of Asian knowledge that has been translated into English from China, Korea, Vietnam and Japan over the last seventy years. -

The Buddhist Cosmopolis: Universal Welfare, Universal Outreach, Universal Message

Journal of Buddhist Studies, Vol. XV, 2018 (Of-print) The Buddhist Cosmopolis: Universal Welfare, Universal Outreach, Universal Message Peter Skilling Published by Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka & The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong JOURNAL OF BUDDHIST STUDIES VOLUME XV CENTRE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES, SRI LANKA & THE BUDDHA-DHARMA CENTRE OF HONG KONG DECEMBER 2018 © Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka & The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong ISBN 978-988-16820-1-7 Published by Centre for Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka & The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong with the sponsorship of the Glorious Sun Charity Group, Hong Kong (旭日慈善基金). EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Ratna Handurukande Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, University of Peradeniya. Y karunadasa Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, University of Kelaniya Visiting Professor, The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong. Oliver abeynayake Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, Buddhist and Pali University of Sri Lanka. Chandima Wijebandara Ph.D. Professor, University of Sri Jayewardenepura. Sumanapala GalmanGoda Ph.D. Professor, University of Kelaniya. Academic Coordinator, Nāgānanda International Institute of Buddhist Studies, Sri Lanka. Toshiichi endo Ph.D. Visiting Professor, Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong. EDITOR Bhikkhu KL dHammajoti 法光 Director, The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong. CONTENTS On the Two Paths Theory: Replies to Criticism 1 Bhikkhu AnālAyo Discourses on the Establishments of Mindfulness (smṛtyupasthānas) Quoted in Śamathadeva’s Abhidharmakośapāyikā-ṭīkā 23 Bhikkhunī DhAmmADinnā