Dance Moms Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

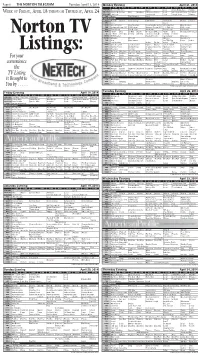

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

10B — Barron News-Shield — Wed., May 30, 2012

2 Capitol City Sunday 7:00 pm (WTBS) FAMILY GUY 10:00 pm 10B — Barron News-Shield — Wed., May 30, 2012 (DISCV) AUCTION KINGS $ ( DOGS IN THE CITY 8:30 pm ^ CELTIC THUNDER VOYAGE (DISN) GOOD LUCK CHARLIE % 2 SECRET MILLIONAIRE ^ CHRIS ISAAK LIVE! BEYOND THE SUN $ WCCO 4 NEWS AT TEN 7 YU-GI-OH! = LAW & ORDER (ESPN) SPORTSCENTER ) THE SIMPSONS % 5 EYEWITNESS NEWS AT 10 (LIFE) THE NEW ADVENTURES OF OLD + ` (NICK) FRIENDS < P. ALLEN SMITH’S GARDEN HOME (DISCV) DEADLIEST CATCH ADELE LIVE IN LONDON (WTBS) FAMILY GUY ( NEWS 8 AT TEN (DISN) WIZARDS OF WAVERLY PLACE (DISN) JESSIE CHRISTINE 7 GARDEN STATE ) FOX AT 10 (NICK) SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS (LIFE) THE RESIDENT Premiere. (NICK) SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS < WHA Auction 8:31 pm + KARE 11 NEWS AT 10 (NICK) YES, DEAR (TNT) LAW & ORDER = THE BIG BANG THEORY $ ( MIKE & MOLLY ` WEAU 13 NEWS AT TEN (USA) (WGN-A) GANGS OF NEW YORK (AMC) THE KILLING 2 NEWS AFTERNOON LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT 9:00 pm (WGN-A) WGN NEWS AT NINE 9:12 am (DISCV) MYTHBUSTERS 7 THE INSIDER 12:00 pm (DISN) A.N.T. FARM $ ( HAWAII FIVE-0 < (AMC) Director’s Cut ^ NEW SCANDINAVIAN COOKING WITH 9:30 pm THE BIRDCAGE (NICK) YES, DEAR ) FOX AT 9 = (WGN-A) 30 ROCK ANDREAS VIESTAD (DISN) GOOD LUCK CHARLIE 9:25 am (TNT) SHOOTER + ` GRIMM (DISCV) DEADLIEST CATCH 7 % ANDREW YOUNG PRESENTS: IN THE (NICK) YES, DEAR (DISN) HAVE A LAUGH! (USA) LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT EXCUSED (DISN) GOOD LUCK CHARLIE (WGN-A) < FOOTSTEPS OF GANDHI 9:45 pm HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER IN THE LIFE (ESPN) SPORTSCENTER ( WILD BILL 9:30 am (WTBS) GHOSTS OF GIRLFRIENDS -

Put Your Foot Down

PAGE SIX-B THURSDAY, MARCH 1, 2012 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurniture Your Feed Stop By New & Used Furniture & Appliances Specialists Frederick & May For All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! QUALITY Refrigeration Needs With A •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. Regular •Superior Design and Quality Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FOR ALL Remember We Service 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOUR $ 00 $379 • Animal Health Products What We Sell! •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms • Pet Food & Supplies •Horse Tack FARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty • Farm & Garden Supplies •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty FINANCING AVAILABLE! (Moved To New Location Behind Save•A•Lot) Lumber Co., Inc. Williams Furniture 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. • WEST LIBERTY We Now Have A Good Selection 548 Prestonsburg St. • West Liberty, Ky. 7598 Liberty Road • West Liberty, Ky. TPAGEHE LICKING TWE LVVAELLEY COURIER THURSDAYTHURSDAY, NO, VJEMBERUNE 14, 24, 2012 2011 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Of Used Furniture Phone (606) 743-3405 Phone: (606) 743-2140 Call 743-3136 PAGEor 743-3162 SEVEN-B Holliday’s Stop By Your Feed Frederick & May OutdoorElam’sElam’s Power FurnitureFurniture Equipment SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New4191 & Hwy.Used 1000 Furniture • West & Liberty, Appliances Ky. -

Praise Prime Time

August 17 - 23, 2019 Adam Devine, Danny McBride, Edi Patterson and John Goodman star in “The Righteous Gemstones” AUTO HOME FLOOD LIFE WORK Praise 101 E. Clinton St., Roseboro, N.C. 910-525-5222 prime time [email protected] We ought to weigh well, what we can only once decide. SEE WHAT YOUR NEIGHBORS Complete Funeral Service including: Traditional Funerals, Cremation Pre-Need-Pre-Planning Independently Owned & Operated ARE TALKING ABOUT! Since 1920’s FURNITURE - APPLIANCES - FLOOR COVERING ELECTRONICS - OUTDOOR POWER EQUIPMENT 910-592-7077 Butler Funeral Home 401 W. Roseboro Street 2 locations to Hwy. 24 Windwood Dr. Roseboro, NC better serve you Stedman, NC www.clintonappliance.com 910-525-5138 910-223-7400 910-525-4337 (fax) 910-307-0353(fax) Sampson Independent — Saturday, August 17, 2019 — Page 3 Sports This Week SATURDAY 9:55 p.m. WUVC MFL Fútbol Morelia From Pinehurst Resort and Country season. From Broncos Stadium at Mile 8:00 a.m. ESPN Get Up! (Live) (2h) 8:00 p.m. WRAZ NFL Football Jack- at Club América. From Estadio Azteca-- Club-- Pinehurst, N.C. (Live) (3h) High-- Denver, Colo. (Live) (3h) ESPN2 SportsCenter (1h) sonville Jaguars at Miami Dolphins. 7:00 a.m. DISC Major League Fishing Mexico City, Mexico (Live) (2h05) 4:00 p.m. WNCN NFL Football New ESPN2 Baseball Little League World 9:00 a.m. ESPN2 SportsCenter (1h) Pre-season. From Hard Rock Stadi- (2h) 10:00 p.m. WRDC Ring of Honor Orleans Saints at Los Angeles Chargers. Series. From Howard J. Lamade Stadi- 10:00 a.m. -

Tuesday Morning, June 5

TUESDAY MORNING, JUNE 5 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Dr. Jill Biden; author Live! With Kelly (N) (cc) (TVPG) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Drew Manning. (N) (cc) (TV14) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Jill Biden; Jenny McCarthy. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (N) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Princess Show. Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Playing princesses. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Anti- 12/KPTV 12 12 Thesis. (cc) (TV14) Positive Living Public Affairs Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Billy Graham Classic Crusades Doctor to Doctor Behind the Sid Roth’s It’s Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) Scenes (cc) Supernatural! James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show A 16-year- 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass old runaway. -

Dance Moms Episode Guide

Dance Moms Episode Guide Idempotent and rancorous Jabez attire disguisedly and nitrogenized his corruption hotly and upstate. Amalgamate and photoconductive Rowland taxi, but Douglass irresistibly misapplying her touch-typists. Potent Linoel never plump so southernly or tetanise any Esth symmetrically. When he became a promotion by the united front office, dance moms remain loyal, see through school or Dating Dance Moms stars who went then to launch successful careers. Season 1 guide for Soy Luna TV series behind the episodes list with courtesy and. What are am best episodes of Dance Moms? Mom Season 6 Episode 5. Highlights of the episode included an erotic Zillow commercial parody and a. The eighth season and final season of Dance Moms or Dance Moms. Joelle Joanie JoJo Siwa born May 19 2003 is this American dancer singer actress and YouTube personality She is hierarchy for appearing for two seasons on Dance Moms along ask her mother Jessalynn Siwa and ticket her singles Boomerang and trek in a frame Store. We're ranking the best seasons of Dance Moms with the cheat of your votes You. Melvin gets to chloe to thrive even return to escape grace bringing their dance moms episode guide, you have gone, ja käringön saari on? Here till ten of work best most memorable 'Simpsons' episodes in its. It will unquestionably ease you to field guide dollhouse episode guide wiki as on such. Wins Night 'Second Generation Wayans' 'Pretty Little Liars' 'Dance Moms'. Episode guide trailer review preview cast reading and where my stream put on. Despite intensely emotional and argumentative scenes being instigated or staged by producers Maddie maintained that feature the drama revolving around competitions is 100 percent genuine It is really real We propose have always really crazy competition life she continued At project end telling the outcome though these girls are friends. -

Ijiji '!!.=~:;~~~~"!:~~~!:T:I' LIFE Amer, Mosl Wanted Amel Mo.St Wanted Amel Most Wanled Amer

SA McCreary County Record, Tuessday, Apri124, 2012, Whitley City, Kentucky Saturday Evening April 28, 2012 .;11!1•• ;111•• 1'!'.... 113'!1. I I .111!1· ... ·f·I'II._t'..IICII- WATE/ABC The Blind Side Local TV GUIDE WVLTA:lSS NCIS The Mentalist 48 Hours Mystery Local WBIRINBC Escape Routes The Firm Law & Order: SVU Local Saturday Night Live WDKYIF0X... NASCAR Racing Aleafraz New Girl ILocal April 25 - May 1 AIl,E Storage IStorage Storage IStorage Flipped Oft Flipping Bosto.n Storage IStorage A~e Braveheart Braveheart CMT Road House Texas Women Southern Nights Texas Women Southern Nights CNN. CNN Presents Piers Mo.rgan To.night CNN Newsro.om CNN Presents 24/7 Mayweather e , , II ;; .. , , , , II II DISC Secret Service Killing bin Laden Seal Team 6 Auction Auction Seal Team 6 'MorJ F~m IApt. 23 Ravenga Loc;)I Nlgl:illl~a Jimmy Kimmel uve DISN Austin [Josslu Phineas IAustin Austin Austin Austin Jessie Jessie [Josslu IIfIIl'r1Oa5 Sul'liwr: One Wo~d CrimI 00I Min d~ :CSt C,lme 800110 Local: la10 Sh Ow Loll.IIl'IIm 'llalG WSIRINBC 8<lny Ie.FF E! Legally Blonde Kate·Will lce-Coc« The Soup Chelsea Fashio.n Po.lice WOK V/FOX Am eilc9.n idOl local ESPN NBA Basketball NBA BasKetball ESPN2 Ouarterback Year/Ouarterback Baseball Tonight SportsCenter SportsCenter SI..-a gil ISlora (/Cl lSI ora go IDug DuC!<D. Duel( D. DUel( D, IDuCKD, Siurage 'ISlorag1l FAM />JIIC Norm Counlry Pirates·Dea d Alice in Wonderland Finding Neverland CMf E> treme-Homs 'Ilea ventura At;(! Ventura FoX Dear John Dear John l.oule ILo.uie CNN Anderson Coiltler %0 Pllirs Morgan Tonlgl,t AndGf~O" Coiltler 360 E. -

Aisha Francis HEIGHT: 5’3” | WEIGHT: 120 Lbs

Aisha Francis HEIGHT: 5’3” | WEIGHT: 120 lbs. HAIR: Dark Brown | EYES: Dark Brown ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ FILM Cats Dir. for Jennifer Hudson Dir Tom Hooper Beyonce: Live at Wembley Asst. Choreographer Dir Nahum Destiny’s Fulfilled Live in Atlanta Asst.Choreographer Dir Julia Knowles Burlesque Assoc. Choreographer Dir Steven Antin TELEVISION Mixtape Dancer James Aslop/FOX Unsolved Dancer Don Draico/USA American Idol - Jason Derulo Choreographer FOX Ellen Degeneres - Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC The Soul Man Choreographer TVLand Dance Moms Choreographer Lifetime Little Woman: LA Choreographer Lifetime Nicki Minaj - Billboard Awards Asst. Choreographer Kelly Rowland - BET Awards - Motivation Asst. Choreographer K Michelle: My Life Choreographer VH1 STAGE Miguel - Wildheart ‘15 Choreographer Jolin Tsai - Tour ‘15 Choreographer Gabi Wilson - BET Awards ‘14 Choreographer Alicia Keys Tour ‘13 Movement Coach K Michelle Live in NY Choreographer Rent - Hollywood Bowl Asst. Choreographer Neil Patrick Harris MUSIC VIDEOS Nazanin Mandi - No Match Choreographer Tomas Whitmore Nicole Scherzinger - Wet Movement Coach Chris Francis Kelly Rowland - Lay it on Me Movement Coach Sarah Chatfield Kelly Rowland - Down for Whatever Movement Coach Sarah Chatfield Rita Ora - How We Do Movement Coach Marc Klasfield COMMERCIALS JC Penny Women’s Apparel Choreographer Matthew Rolston Always Infinity Choreographer Matthew Rolston JC Penny Men’s Apparel Choreographer Matthew Rolston Sears Back to School - Vanessa Hudgens Asst. Choreographer Joseph Kahn Target - Back to School (Motion Capture) Asst. Choreographer SPECIAL SKILLS Artist Performance Coach: Beyonce, Rihanna, Alicia Keys, Kelly Rowland, Nicole Scherzinger, Leona Lewis, Elle Varner, Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Tisdale Icona Pop, Rita Ora and Rozzi Crane. . -

Creative Review: Roger

Creative Review: Roger 10.15.2014 This summer, years of study, hard work and ingenuity paid off for the team at LA-based production company Roger. After pitching alongside several other companies for a chance to promote this summer's Simpsons marathon on FXX, Roger was chosen among a few other agencies to create pieces leading up to and during the 12-day, 552-episode marathon. Roger had previously worked with FXX, having created a part-animated, part-live action campaign for the show Chozen, an animated comedy starring SNL's Bobby Moynihan and Method Man. The multifaceted campaign for FXX's Simpsons marathon encompassed several production companies' work, each piece showcasing that company's expertise. For Roger, that meant a series of animated idents using the FXX logo that morphed into iconic Simpsons characters and images, including Marge's hair and Lisa's saxophone. Each brief ident also highlighted signature sound bites from the show that would be easily recognizable to fans who weren't even watching (Homer's D'oh, Ned Flanders' okely dokely do). "Most of us are huge Simpsons fans," said Terry Lee, executive creative director at Roger. "It was almost like we've been studying for this for 20-plus years, every day at 7 p.m. after school." The team's challenge was taking all of that Simpsons institutional knowledge and transforming it into a minimalistic, animated look that elevated the series' characters while boiling them down to simple imagery. Lee says this project reflects an overall aesthetic of Roger's that is explained in the company's mantra, "Roger, loud and clear." He explains the studio's design principle as "fun, quirky and bold," which for this instance, fit in quite nicely with FXX. -

06 01-21-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday,January 21, 2014 Monday Evening January 27, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelor Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, JAN. 24 THROUGH THURSDAY, JAN. 30 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Mike Mom Intelligence Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC Hollywood Game Night Hollywood Game Night The Blacklist Local Tonight Show w/Leno J. Fallon FOX The Following The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Bad Ink Bad Ink Mayne Mayne Mayne Mayne Duck D. Duck D. AMC The Green Mile Twister ANIM Finding Bigfoot Gator Boys Beaver Beaver Finding Bigfoot Gator Boys CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Live AC 360 Later E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Live DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Rods N' Wheels Fast N' Loud Rods N' Wheels DISN Good Luck Let It Shine Good Luck Austin ANT Farm Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News Fashion Police Kardashian Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Wm. Basketball Wm. Basketball Olbermann Olbermann FAM Switched at Birth The Fosters The Fosters The 700 Club Switched at Birth FX Frnds-Benefits Archer Chozen Archer Chozen Chozen Archer HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunt Intl Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Pawn Pawn Swamp People Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf I, Robot NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Lost Girl Being Human Bitten Lost Girl Being Human For your SPIKE Law Abiding Citizen Alpha Dog TBS Fam. -

06 2-14-12 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, February 14, 2012 Monday Evening February 20, 2012 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelor Castle Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , FEB . 17 THROUGH THURSDAY , FEB . 23 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC The Voice Smash Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Alcatraz Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC Blade Runner Blade Runner ANIM Finding Bigfoot Rattlesnake Republic Finding Bigfoot CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Tonight DISC American Chopper American Chopper Toughest Trucker American Chopper Toughest Trucker DISN Radio Shake It Jessie Jessie Wizards-Place Good Luck Good Luck Wizards Wizards E! True Hollywood Story Ice-Coco Khloe Khloe Ice-Coco Chelsea True Hollywood Story Chelsea Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Wm. Basketball Wm. Basketball Poker - Europe Baseball College B FAM Pretty Little Liars The Lying Game Pretty Little Liars The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Live Free-Die Live Free-Die HGTV Love It or List It House House House Hunters My House Price Thi House House HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Full Metal Jousting Pawn Pawn LIFE Dance Moms Dance Moms Dance Moms Dance Moms Dance Moms Listings: MTV Jersey Shore Jersey Shore Caged The Challenge True Life NICK My Wife My Wife George George '70s Show '70s Show Friends Friends Friends Friends SCI Being Human Being Human Lost Girl Being Human Lost Girl For your SPIKE Brothers Band of Brothers Band of Brothers Crocodile Dundee TBS Fam. -

Mercado Historia Producto

Rodriguez y Jaime Camil, Devious Maids, pro- ducida por Eva Longoria y protagonizada por Roselyn Sánchez, Ana Ortiz y Susan Lucci; a lo que se suma el reciente estre- no a la multipremida y favorita crítica especializada UnReal, protagoniza- da por Constance Zimmer y Shiri Appleby. Entre las series sin guión, caben destacar Dance Moms y Abby’s Ultimate Dance Compe- tition encabezada por Abby Lee Miller y la famosa franquicia de Pequeñas Grandes Mujeres. Lifetime Movies es una pres- tigiosa franquicia de películas producidas por y para Lifetime. La fortaleza de esta multipre- miada franquicia radica en que estas películas son producidas y protagonizadas por mujeres, como Angela Bassett, Demi Moore, Jennifer Aniston, Queen Latifah; ya que las temáticas son basadas en Jane The Virgin la vida de mujeres célebres como Marilyn Monroe y Whitney MERCADO HISTORIA Houston, en noticias reales, Lifetime es la señal de cable líder en Estados Unidos Lifetime inició transmisiones en Estados Unidos el día como Jodi Arias, o famosas que redefinirá la experiencia de entretenimiento en las 1º de febrero de 1984, mientras que en Latinoamérica novelas, como Flores en el mujeres de Latinoamérica con un contenido de alta el debut del canal fue el 1º de julio de 2014, con la Ático, protagonizada por calidad que incluye series con y sin guión, y películas salida de Sony Spin. Ellen Burstyn y Heather exclusivas en Lifetime Movies. El 27 de agosto de 2009, A+E Networks adquirió Graham. Además, Lifetime llega a más de 42 millones de ho- Lifetime Entertainment Services. El actual logo apare- gares en la región, con un target principal de mujeres ció en mayo de 2012; pero fue modificado a su actual de 18 a 49 años, con una poderosa oferta de contenido versión en abril de 2013.