Arxiv:2009.08431V1 [Math.HO] 17 Sep 2020 Integral Tables, There Can Be Difficulties and Drawbacks Occasioned by Their Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECE3040: Table of Contents

ECE3040: Table of Contents Lecture 1: Introduction and Overview Instructor contact information Navigating the course web page What is meant by numerical methods? Example problems requiring numerical methods What is Matlab and why do we need it? Lecture 2: Matlab Basics I The Matlab environment Basic arithmetic calculations Command Window control & formatting Built-in constants & elementary functions Lecture 3: Matlab Basics II The assignment operator “=” for defining variables Creating and manipulating arrays Element-by-element array operations: The “.” Operator Vector generation with linspace function and “:” (colon) operator Graphing data and functions Lecture 4: Matlab Programming I Matlab scripts (programs) Input-output: The input and disp commands The fprintf command User-defined functions Passing functions to M-files: Anonymous functions Global variables Lecture 5: Matlab Programming II Making decisions: The if-else structure The error, return, and nargin commands Loops: for and while structures Interrupting loops: The continue and break commands Lecture 6: Programming Examples Plotting piecewise functions Computing the factorial of a number Beeping Looping vs vectorization speed: tic and toc commands Passing an “anonymous function” to Matlab function Approximation of definite integrals: Riemann sums Computing cos(푥) from its power series Stopping criteria for iterative numerical methods Computing the square root Evaluating polynomials Errors and Significant Digits Lecture 7: Polynomials Polynomials -

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma November 22, 2002 Contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1. Integrals 6 1.1. Areas and Distances. The Definite Integral 6 1.2. The Evaluation Theorem 11 1.3. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus 14 1.4. The Substitution Rule 16 1.5. Integration by Parts 21 1.6. Trigonometric Integrals and Trigonometric Substitutions 26 1.7. Partial Fractions 32 1.8. Integration using Tables and CAS 39 1.9. Numerical Integration 41 1.10. Improper Integrals 46 Chapter 2. Applications of Integration 50 2.1. More about Areas 50 2.2. Volumes 52 2.3. Arc Length, Parametric Curves 57 2.4. Average Value of a Function (Mean Value Theorem) 61 2.5. Applications to Physics and Engineering 63 2.6. Probability 69 Chapter 3. Differential Equations 74 3.1. Differential Equations and Separable Equations 74 3.2. Directional Fields and Euler’s Method 78 3.3. Exponential Growth and Decay 80 Chapter 4. Infinite Sequences and Series 83 4.1. Sequences 83 4.2. Series 88 4.3. The Integral and Comparison Tests 92 4.4. Other Convergence Tests 96 4.5. Power Series 98 4.6. Representation of Functions as Power Series 100 4.7. Taylor and MacLaurin Series 103 3 CONTENTS 4 4.8. Applications of Taylor Polynomials 109 Appendix A. Hyperbolic Functions 113 A.1. Hyperbolic Functions 113 Appendix B. Various Formulas 118 B.1. Summation Formulas 118 Appendix C. Table of Integrals 119 Introduction These notes are intended to be a summary of the main ideas in course MATH 214-2: Integral Calculus. -

Package 'Mosaiccalc'

Package ‘mosaicCalc’ May 7, 2020 Type Package Title Function-Based Numerical and Symbolic Differentiation and Antidifferentiation Description Part of the Project MOSAIC (<http://mosaic-web.org/>) suite that provides utility functions for doing calculus (differentiation and integration) in R. The main differentiation and antidifferentiation operators are described using formulas and return functions rather than numerical values. Numerical values can be obtained by evaluating these functions. Version 0.5.1 Depends R (>= 3.0.0), mosaicCore Imports methods, stats, MASS, mosaic, ggformula, magrittr, rlang Suggests testthat, knitr, rmarkdown, mosaicData Author Daniel T. Kaplan <[email protected]>, Ran- dall Pruim <[email protected]>, Nicholas J. Horton <[email protected]> Maintainer Daniel Kaplan <[email protected]> VignetteBuilder knitr License GPL (>= 2) LazyLoad yes LazyData yes URL https://github.com/ProjectMOSAIC/mosaicCalc BugReports https://github.com/ProjectMOSAIC/mosaicCalc/issues RoxygenNote 7.0.2 Encoding UTF-8 NeedsCompilation no Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2020-05-07 13:00:13 UTC 1 2 D R topics documented: connector . .2 D..............................................2 findZeros . .4 fitSpline . .5 integrateODE . .5 numD............................................6 plotFun . .7 rfun .............................................7 smoother . .7 spliner . .7 Index 8 connector Create an interpolating function going through a set of points Description This is defined in the mosaic package: See connector. D Derivative and Anti-derivative operators Description Operators for computing derivatives and anti-derivatives as functions. Usage D(formula, ..., .hstep = NULL, add.h.control = FALSE) antiD(formula, ..., lower.bound = 0, force.numeric = FALSE) makeAntiDfun(.function, .wrt, from, .tol = .Machine$double.eps^0.25) numerical_integration(f, wrt, av, args, vi.from, ciName = "C", .tol) D 3 Arguments formula A formula. -

Calculus 141, Section 8.5 Symbolic Integration Notes by Tim Pilachowski

Calculus 141, section 8.5 Symbolic Integration notes by Tim Pilachowski Back in my day (mid-to-late 1970s for high school and college) we had no handheld calculators, and the only electronic computers were mainframes at universities and government facilities. After learning the integration techniques that you are now learning, we were sent to Tables of Integrals, which listed results for (often) hundreds of simple to complicated integration results. Some could be evaluated using the methods of Calculus 1 and 2, others needed more esoteric methods. It was necessary to scan the Tables to find the form that was needed. If it was there, great! If not… The UMCP Physics Department posts one from the textbook they use (current as of 2017) at www.physics.umd.edu/hep/drew/IntegralTable.pdf . A similar Table of Integrals from http://www.had2know.com/academics/table-of-integrals-antiderivative-formulas.html is appended at the end of this Lecture outline. x 1 x Example F from 8.1: Evaluate e sindxx using a Table of Integrals. Answer : e ()sin x − cos x + C ∫ 2 If you remember, we had to define I, do a series of two integrations by parts, then solve for “ I =”. From the Had2Know Table of Integrals below: Identify a = and b = , then plug those values in, and voila! Now, with the development of handheld calculators and personal computers, much more is available to us, including software that will do all the work. The text mentions Derive, Maple, Mathematica, and MATLAB, and gives examples of Mathematica commands. You’ll be using MATLAB in Math 241 and several other courses. -

Symbolic and Numerical Integration in MATLAB 1 Symbolic Integration in MATLAB

Symbolic and Numerical Integration in MATLAB 1 Symbolic Integration in MATLAB Certain functions can be symbolically integrated in MATLAB with the int command. Example 1. Find an antiderivative for the function f(x)= x2. We can do this in (at least) three different ways. The shortest is: >>int(’xˆ2’) ans = 1/3*xˆ3 Alternatively, we can define x symbolically first, and then leave off the single quotes in the int statement. >>syms x >>int(xˆ2) ans = 1/3*xˆ3 Finally, we can first define f as an inline function, and then integrate the inline function. >>syms x >>f=inline(’xˆ2’) f = Inline function: >>f(x) = xˆ2 >>int(f(x)) ans = 1/3*xˆ3 In certain calculations, it is useful to define the antiderivative as an inline function. Given that the preceding lines of code have already been typed, we can accomplish this with the following commands: >>intoff=int(f(x)) intoff = 1/3*xˆ3 >>intoff=inline(char(intoff)) intoff = Inline function: intoff(x) = 1/3*xˆ3 1 The inline function intoff(x) has now been defined as the antiderivative of f(x)= x2. The int command can also be used with limits of integration. △ Example 2. Evaluate the integral 2 x cos xdx. Z1 In this case, we will only use the first method from Example 1, though the other two methods will work as well. We have >>int(’x*cos(x)’,1,2) ans = cos(2)+2*sin(2)-cos(1)-sin(1) >>eval(ans) ans = 0.0207 Notice that since MATLAB is working symbolically here the answer it gives is in terms of the sine and cosine of 1 and 2 radians. -

Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative

1 Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative: A function F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I if for all x in I. Representation of Antiderivatives: If F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I, then G is an antiderivative of f on the interval I if and only if G is of the form G(x) = F(x) + C, for all x in I where C is a constant. Sigma Notation: The sum of n terms a1,a2,a3,…,an is written as where I is the index of summation, ai is the ith term of the sum, and the upper and lower bounds of summation are n and 1. Summation Formulas: 1. 2. 3. 4. Limits of the Lower and Upper Sums: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The limits as n of both the lower and upper sums exist and are equal to each other. That is, where are the minimum and maximum values of f on the subinterval. Definition of the Area of a Region in the Plane: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The area if a region bounded by the graph of f, the x-axis and the vertical lines x=a and x=b is Area = where . Definition of a Riemann Sum: Let f be defined on the closed interval [a,b], and let be a partition of [a,b] given by a =x0<x1<x2<…<xn-1<xn=b where xi is the width of the ith subinterval. -

Integration Benchmarks for Computer Algebra Systems

The Electronic Journal of Mathematics and Technology, Volume 2, Number 3, ISSN 1933-2823 Integration on Computer Algebra Systems Kevin Charlwood e-mail: [email protected] Washburn University Topeka, KS 66621 Abstract In this article, we consider ten indefinite integrals and the ability of three computer algebra systems (CAS) to evaluate them in closed-form, appealing only to the class of real, elementary functions. Although these systems have been widely available for many years and have undergone major enhancements in new versions, it is interesting to note that there are still indefinite integrals that escape the capacity of these systems to provide antiderivatives. When this occurs, we consider what a user may do to find a solution with the aid of a CAS. 1. Introduction We will explore the use of three CAS’s in the evaluation of indefinite integrals: Maple 11, Mathematica 6.0.2 and the Texas Instruments (TI) 89 Titanium graphics calculator. We consider integrals of real elementary functions of a single real variable in the examples that follow. Students often believe that a good CAS will enable them to solve any problem when there is a known solution; these examples are useful in helping instructors show their students that this is not always the case, even in a calculus course. A CAS may provide a solution, but in a form containing special functions unfamiliar to calculus students, or too cumbersome for students to use directly, [1]. Students may ask, “Why do we need to learn integration methods when our CAS will do all the exercises in the homework?” As instructors, we want our students to come away from their mathematics experience with some capacity to make intelligent use of a CAS when needed. -

Sequences, Series and Taylor Approximation (Ma2712b, MA2730)

Sequences, Series and Taylor Approximation (MA2712b, MA2730) Level 2 Teaching Team Current curator: Simon Shaw November 20, 2015 Contents 0 Introduction, Overview 6 1 Taylor Polynomials 10 1.1 Lecture 1: Taylor Polynomials, Definition . .. 10 1.1.1 Reminder from Level 1 about Differentiable Functions . .. 11 1.1.2 Definition of Taylor Polynomials . 11 1.2 Lectures 2 and 3: Taylor Polynomials, Examples . ... 13 x 1.2.1 Example: Compute and plot Tnf for f(x) = e ............ 13 1.2.2 Example: Find the Maclaurin polynomials of f(x) = sin x ...... 14 2 1.2.3 Find the Maclaurin polynomial T11f for f(x) = sin(x ) ....... 15 1.2.4 QuestionsforChapter6: ErrorEstimates . 15 1.3 Lecture 4 and 5: Calculus of Taylor Polynomials . .. 17 1.3.1 GeneralResults............................... 17 1.4 Lecture 6: Various Applications of Taylor Polynomials . ... 22 1.4.1 RelativeExtrema .............................. 22 1.4.2 Limits .................................... 24 1.4.3 How to Calculate Complicated Taylor Polynomials? . 26 1.5 ExerciseSheet1................................... 29 1.5.1 ExerciseSheet1a .............................. 29 1.5.2 FeedbackforSheet1a ........................... 33 2 Real Sequences 40 2.1 Lecture 7: Definitions, Limit of a Sequence . ... 40 2.1.1 DefinitionofaSequence .......................... 40 2.1.2 LimitofaSequence............................. 41 2.1.3 Graphic Representations of Sequences . .. 43 2.2 Lecture 8: Algebra of Limits, Special Sequences . ..... 44 2.2.1 InfiniteLimits................................ 44 1 2.2.2 AlgebraofLimits.............................. 44 2.2.3 Some Standard Convergent Sequences . .. 46 2.3 Lecture 9: Bounded and Monotone Sequences . ..... 48 2.3.1 BoundedSequences............................. 48 2.3.2 Convergent Sequences and Closed Bounded Intervals . .... 48 2.4 Lecture10:MonotoneSequences . -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

VSDITLU: a Verifiable Symbolic Definite Integral Table Look-Up

VSDITLU: a verifiable symbolic definite integral table look-up A. A. Adams, H. Gottliebsen, S. A. Linton, and U. Martin Department of Computer Science, University of St Andrews, St Andrews KY16 9ES, Scotland {aaa,hago,sal,um}@cs.st-and.ac.uk Abstract. We present a verifiable symbolic definite integral table look-up: a sys- tem which matches a query, comprising a definite integral with parameters and side conditions, against an entry in a verifiable table and uses a call to a library of facts about the reals in the theorem prover PVS to aid in the transformation of the table entry into an answer. Our system is able to obtain correct answers in cases where standard techniques implemented in computer algebra systems fail. We present the full model of such a system as well as a description of our prototype implementation showing the efficacy of such a system: for example, the prototype is able to obtain correct answers in cases where computer algebra systems [CAS] do not. We extend upon Fateman’s web-based table by including parametric limits of integration and queries with side conditions. 1 Introduction In this paper we present a verifiable symbolic definite integral table look-up: a system which matches a query, comprising a definite integral with parameters and side condi- tions, against an entry in a verifiable table, and uses a call to a library of facts about the reals in the theorem prover PVS to aid in the transformation of the table entry into an answer. Our system is able to obtain correct answers in cases where standard tech- niques, such as those implemented in the computer algebra systems [CAS] Maple and Mathematica, do not. -

13.1 Antiderivatives and Indefinite Integrals

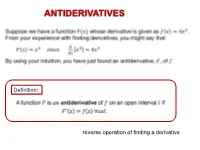

ANTIDERIVATIVES Definition: reverse operation of finding a derivative Notice that F is called AN antiderivative and not THE antiderivative. This is easily understood by looking at the example above. Some antiderivatives of 푓 푥 = 4푥3 are 퐹 푥 = 푥4, 퐹 푥 = 푥4 + 2, 퐹 푥 = 푥4 − 52 Because in each case 푑 퐹(푥) = 4푥3 푑푥 Theorem 1: If a function has more than one antiderivative, then the antiderivatives differ by a constant. • The graphs of antiderivatives are vertical translations of each other. • For example: 푓(푥) = 2푥 Find several functions that are the antiderivatives for 푓(푥) Answer: 푥2, 푥2 + 1, 푥2 + 3, 푥2 − 2, 푥2 + 푐 (푐 푖푠 푎푛푦 푟푒푎푙 푛푢푚푏푒푟) INDEFINITE INTEGRALS Let f (x) be a function. The family of all functions that are antiderivatives of f (x) is called the indefinite integral and has the symbol f (x) dx The symbol is called an integral sign, The function 푓 (푥) is called the integrand. The symbol 푑푥 indicates that anti-differentiation is performed with respect to the variable 푥. By the previous theorem, if 퐹(푥) is any antiderivative of 푓, then f (x) dx F(x) C The arbitrary constant C is called the constant of integration. Indefinite Integral Formulas and Properties Vocabulary: The indefinite integral of a function 푓(푥) is the family of all functions that are antiderivatives of 푓 (푥). It is a function 퐹(푥) whose derivative is 푓(푥). The definite integral of 푓(푥) between two limits 푎 and 푏 is the area under the curve from 푥 = 푎 to 푥 = 푏. -

The 30 Year Horizon

The 30 Year Horizon Manuel Bronstein W illiam Burge T imothy Daly James Davenport Michael Dewar Martin Dunstan Albrecht F ortenbacher P atrizia Gianni Johannes Grabmeier Jocelyn Guidry Richard Jenks Larry Lambe Michael Monagan Scott Morrison W illiam Sit Jonathan Steinbach Robert Sutor Barry T rager Stephen W att Jim W en Clifton W illiamson Volume 10: Axiom Algebra: Theory i Portions Copyright (c) 2005 Timothy Daly The Blue Bayou image Copyright (c) 2004 Jocelyn Guidry Portions Copyright (c) 2004 Martin Dunstan Portions Copyright (c) 2007 Alfredo Portes Portions Copyright (c) 2007 Arthur Ralfs Portions Copyright (c) 2005 Timothy Daly Portions Copyright (c) 1991-2002, The Numerical ALgorithms Group Ltd. All rights reserved. This book and the Axiom software is licensed as follows: Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without modification, are permitted provided that the following conditions are met: - Redistributions of source code must retain the above copyright notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer. - Redistributions in binary form must reproduce the above copyright notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer in the documentation and/or other materials provided with the distribution. - Neither the name of The Numerical ALgorithms Group Ltd. nor the names of its contributors may be used to endorse or promote products derived from this software without specific prior written permission. THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS AND CONTRIBUTORS "AS IS" AND ANY EXPRESS