The Money Chase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017-2018 2

ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR ___________________________________ 3 THE KENNETH L. MADDY INSTITUTE ______________________________ 5 Introduction _____________________________________________________________ 5 Mission _________________________________________________________________ 5 Objectives ______________________________________________________________ 5 GOVERNANCE HISTORY ________________________________________ 6 UNIT FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FUNDING _______________________ 8 BOARD OF DIRECTORS _________________________________________ 9 2017-2018 PROGRAMS AND ACTIVITIES __________________________ 10 Civic Engagement _______________________________________________________ 10 Government Leadership __________________________________________________ 11 Wonderful Fellowship ___________________________________________________ 12 Policy Analysis __________________________________________________________ 13 FUNDRAISING _________________________________________________ 17 EFFECTIVENESS AND IMPACT ___________________________________ 19 2018-2019 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES _____________________________ 21 OTHER ACTIVITIES _____________________________________________ 22 3 A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR Attached is the Annual Report of the Maddy Institute as is required for all ancillary units. The Institute has contributed to the overall mission of the University through policy analysis, civic engagement and leadership training by engaging, preparing and inspiring a new generation of governmental, non-profit, business -

Everyone's America

Everyone's America State Policies for an Equal Say in Our Democracy and an Equal Chance in Our Economy Spring 2018 Edition ABOUT DEMOS Dēmos is a public policy organization working for an America where we all have an equal say in our democracy and an equal chance in our economy. Our name means “the people.” It is the root word of democracy, and it reminds us that in America, the true source of our greatness is the diversity of our people. Our nation’s highest challenge is to create a democracy that truly empowers people of all backgrounds, so that we all have a say in setting the policies that shape opportunity and provide for our common future. To help America meet that challenge, Dēmos is working to reduce both political and economic inequality, deploying original research, advocacy, litigation, and strategic communications to create the America the people deserve. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Allie Boldt, Connie Razza, Amy Traub CONTRIBUTORS Algernon Austin, Naila Awan, Lew Daly, Vijay Das, Mark Huelsman, Stuart Naifeh, Lori Shellenberger SPECIAL THANKS TO Shanaé Bass, Viviana Bernal, Arlene Corbin Lewis, Katherine Culliton-González, Liz Doyle, Tamara Draut, Gwyn Ellsworth, Lynn Kanter, Carol Lautier, Adam Lioz, Rodney McKenzie, Adrien Salazar, Brenda Wright, and our designers at Sidedoor Studio. Thanks also to the many leaders of movement organizations who took the time to talk with us and share the expertise and perspectives of their members. demos.org 80 Broad St., 4th Fl. New York, NY 10004 Media Contact [email protected] © 2018 Dēmos This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International license. -

Siskiyou County Clerk's Office June 5, 2018 Statewide Direct Primary Election Report #7- Certified Final Results -June 21, 2018

Page: 1 of 12 6/22/201 8 8:45:56 AM SISKIYOU COUNTY CLERK'S OFFICE JUNE 5, 2018 STATEWIDE DIRECT PRIMARY ELECTION REPORT #7- CERTIFIED FINAL RESULTS -JUNE 21, 2018 Precincts Reported: 56 of 56 (100.00%) Registered Voters: 11 ,796 of 27, 311 (43.19%) Ballots Cast: 23,604 Page: 2 of 12 6/22/2018 8:45:56 AM GOVERNOR Vote for ONE (Vote for 1) Precincts Reported: 56 of 56 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 11,796 / 27,311 43.19% Candidate Total JOHN H.COX 3,968 34.46% GAVIN NEWSOM 2,688 23.34% TRAVIS ALLEN 2,134 18.53% JOHN CHIANG 577 5.01% DELAINE EASTIN 530 4.60% ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA 397 3.45% AMANDA RENTERIA 285 2.47% PETER Y. LIU 129 1.12% MICHAEL SHELLENBERGER 118 1.02% ROBERT C. NEWMAN, 11 104 0.90% YVONNE GIRARD 99 0.86% JOSH JONES 90 0.78% J. BRIBIESCA 88 0.76% ZOLTAN ISTVAN 52 0.45% GLORIA ESTELA LA RIVA so 0.43% NICKOLAS WILDSTAR 36 0.31% JOHNNY WATIENSURG 34 0.30% ROBERT DAVIDSON GRIFFIS 32 0.28% CHRISTOPHER N. CARLSON 26 0.23% THOMAS JEFFERSON CARES 17 0.15% DESMOND SILVEIRA 14 0.12% ALBERT CAESAR MEZZETII 13 0.11% AKINYEMI AGBEDE 10 0.09% JEFFREY EDWARD TAYLOR 10 0.09% HAKAN "HAWK" MIKADO 10 0.09% KLEMENT TINAJ 3 0.03% SHUBHAM GOEL 2 0.02% Write-in 0 0.00% Total Votes 11,516 Total K. PEARCE WRITE-IN 0 0.00% VERONIKA FIMBRES WRITE-IN 0 0.00% ARMANDO M. -

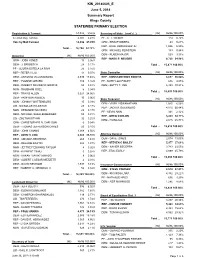

Statewide Primary Election Summary Report 6.26.18

KIN_20180605_E June 5, 2018 Summary Report Kings County STATEWIDE PRIMARY ELECTION Registration & Turnout 51,342 Voters Secretary of State (cont'd...) (86) 86/86 100.00% Election Day Turnout 2,707 5.27% PF - C. T. WEBER 114 0.72% Vote by Mail Turnout 14,092 27.45% GRN - ERIK RYDBERG 43 0.27% REP - RAUL RODRIGUEZ JR 1,046 6.59% Total ... 16,799 32.72% GRN - MICHAEL FEINSTEIN 133 0.84% DEM - RUBEN MAJOR 529 3.33% Governor (86) 86/86 100.00% REP - MARK P. MEUSER 8,726 54.98% GRN - JOSH JONES 10 0.06% DEM - J. BRIBIESCA 28 0.17% Total ... 15,871 100.00% PF - GLORIA ESTELA LA RIVA 25 0.15% REP - PETER Y LIU 11 0.07% State Controller (86) 86/86 100.00% DEM - ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA 2,836 17.40% REP - KONSTANTINOS RODITIS 8,637 55.04% REP - YVONNE GIRARD 189 1.16% PF - MARY LOU FINLEY 636 4.05% DEM - ROBERT DAVIDSON GRIFFIS 55 0.34% DEM - BETTY T. YEE 6,420 40.91% NON - SHUBHAM GOEL 6 0.04% Total ... 15,693 100.00% REP - TRAVIS ALLEN 3,921 24.06% DEM - AKINYEMI AGBEDE 10 0.06% State Treasurer (86) 86/86 100.00% NON - JOHNNY WATTENBURG 15 0.09% DEM - VIVEK VISWANATHAN 1,025 6.56% LIB - NICKOLAS WILDSTAR 28 0.17% REP - JACK M. GUERRERO 4,815 30.84% NON - DESMOND SILVEIRA 28 0.17% PF - KEVIN AKIN 331 2.12% DEM - MICHAEL SHELLENBERGER 50 0.31% REP - GREG CONLON 5,429 34.77% LIB - ZOLTAN ISTVAN 32 0.20% DEM - FIONA MA 4,015 25.71% GRN - CHRISTOPHER N. -

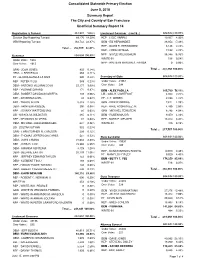

Summary Report the City and County of San Francisco Unofficial Summary Report 14

Consolidated Statewide Primary Election June 5, 2018 Summary Report The City and County of San Francisco Unofficial Summary Report 14 Registration & Turnout 481,991 Voters Lieutenant Governor (cont'd...) 604/604 100.00% Election Day Reporting Turnout 89,176 18.50% REP - COLE HARRIS 10,927 4.92% VBM Reporting Turnout 163,743 33.97% DEM - ED HERNANDEZ 38,854 17.49% REP - DAVID R. HERNANDEZ 5,146 2.32% Total ... 252,919 52.47% REP - LYDIA ORTEGA 7,162 3.22% Governor 604/604 100.00% NPP - GAYLE MCLAUGHLIN 36,348 16.36% WRITE-IN 536 0.24% Under Votes: 5066 Over Votes: 4012 NPP - WRITE-IN MARJAN S. FARIBA 0 0.00% GRN - JOSH JONES 822 0.34% Total ... 222,158 100.00% DEM - J. BRIBIESCA 266 0.11% PF - GLORIA ESTELA LA RIVA 820 0.34% Secretary of State 604/604 100.00% REP - PETER Y LIU 549 0.23% Under Votes: 34864 DEM - ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA 22,177 9.09% Over Votes: 298 REP - YVONNE GIRARD 171 0.07% DEM - ALEX PADILLA 165,730 76.11% DEM - ROBERT DAVIDSON GRIFFIS 139 0.06% LIB - GAIL K. LIGHTFOOT 4,943 2.27% NPP - SHUBHAM GOEL 38 0.02% PF - C.T. WEBER 2,898 1.33% REP - TRAVIS ALLEN 5,318 2.18% GRN - ERIK RYDBERG 2,621 1.20% DEM - AKINYEMI AGBEDE 205 0.08% REP - RAUL RODRIGUEZ JR 4,490 2.06% NPP - JOHNNY WATTENBURG 56 0.02% GRN - MICHAEL FEINSTEIN 8,788 4.04% LIB - NICKOLAS WILDSTAR 265 0.11% DEM - RUBEN MAJOR 9,459 4.34% NPP - DESMOND SILVEIRA 87 0.04% REP - MARK P. -

Special Municipal Election June 6, 2018

RESOLUTION NO. ___ A RESOLUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF SANTA BARBARA CERTIFYING THE ELECTION RESULTS OF THE OFFICIAL CANVASS FOR THE SPECIAL MUNICIPAL ELECTION HELD IN THE CITY ON JUNE 6, 2018 WHEREAS, on Tuesday, June 6, 2018, a Special Municipal Election was held in the City of Santa Barbara to elect a City Councilmember to represent District 3 for the remainder of the term expiring at the end of 2019; WHEREAS, by its Resolution No. 18-010, adopted on February 6, 2018, the City Council requested the Board of Supervisors of the County of Santa Barbara to consolidate the Special Municipal Election with the Statewide Direct Primary Election; WHEREAS, the Special Municipal Election was consolidated with the Statewide Direct Primary Election on June 6, 2018; and WHEREAS, the County Clerk, Recorder and Assessor & Registrar of Voters of the County of Santa Barbara has completed a canvass of election results and submitted to the City the Certification of Election Results of the Official Canvass. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF SANTA BARBARA AS FOLLOWS: SECTION 1. The City Council does hereby certify the Election Results of the Official Canvass of the Special Municipal Election consolidated with the Statewide Primary Election held in the City of Santa Barbara on Tuesday, June 6, 2018, as shown on the attached Certification of Election Results of the Official Canvass, dated June 25, 2018, and marked as "Exhibit A." SECTION 2. The City Clerk shall certify to the passage and adoption of this Resolution and enter it into the book of original Resolutions. -

Vote Early and Avoid the Crush There’S No Need to Wait an Entire Month to Vote Required by Virginia State Law

Vol. 41, No 10 www.arlingtondemocrats.org October 2016 Vote early and avoid the crush There’s no need to wait an entire month to vote required by Virginia state law. for Hillary Clinton and Tim Kaine. You can cast The application form takes 30 seconds to fill your vote right now. And ACDC urges everyone to out and then you vote by filling in a paper ballot— cast your ballot early. just like in the olden days of the 20th Century!—but First of all, it’s convenient because you pick then inserting the paper ballot into one of the the day. And you avoid the huge lines that are seen county’s brand-new scanners that count the votes. every presidential year. But many miss voting on You can also vote by mail if you prefer—and Election Day because they have a crunch at the of- don’t forget any kids away at college. An applica- Yes, Virginia, we have fice, were called out of town or wake up ill. All tion for a mail-in ballot can be obtained on the found election fraud in that’s avoided by voting before Election Day. County webpage at: The technical term is “in-person absentee vot- http://vote.arlingtonva.us/absentee/absentee-voting- Virginia. It’s spread all ing,” but it just means voting in the weeks before ballot-application/ over Page Eight! actual Election Day. The three locations for voting early this year Voting is in the lobby of the County Building, are: 2100 Clarendon Blvd. And this year there are two • In the lobby of the County Building at Court- other locations, in north and south Arlington, to house Plaza, 2100 Clarendon Blvd. -

Uncorrected Transcript

1 POLITICS-2014/09/30 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION WHAT THE 2014 PRIMARIES FORETELL ABOUT THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN POLITICS Washington, D.C. Tuesday, September 30, 2014 PARTICIPANTS: The Primary Election Universe: DONNA BRAZILE, Moderator Founder and Managing Director Brazile & Associates LLC ELAINE KAMARCK Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Effective Public Management The Brookings Institution WALTER SHAPIRO Columnist, PoliticsDaily.com JILL LAWRENCE National Columnist, Creators Syndicate Primaries and Campaign Finance: ELAINE KAMARCK, Moderator Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Effective Public Management The Brookings Institution ROBERT BOATRIGHT Associate Professor of Political Science Clark University MICHAEL MALBIN Co-Founder and Executive Director, Campaign Finance Institute Professor of Political Science, University at Albany, SUNY * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 POLITICS-2014/09/30 P R O C E E D I N G S MS. BRAZILE: Thank you so much for being here. I’m Donna Brazile, and let me tell you delighted I am to moderate this event. As you know, there are 5 weeks remaining in the 2014 midterm election, and the Primaries Project is a culmination of 9 months of work by two research institutions: Brookings and the Campaign Finance Institute. Together, they have undertaken, I think, one of the most comprehensive looks ever at the primary candidates for both the United States House as well as the United States Senate. Now, the Brookings team set out to study nearly every single candidate who ran for Congress in the 2014 cycle. That’s all 1662 of them, something that has never been done before. -

The Money Chase

The Money Chase Moving from Big Money Dominance in the 2014 Midterms to a Small Donor Democracy adam lioz karen shanton candidate profiles by emma boorboor, michael russo & dan smith About Demos Demos is a public policy organization working for an America where we all have an equal say in our democracy and an equal chance in our economy. Our name means “the people.” It is the root word of democracy, and it reminds us that in America, the true source of our greatness is the diversity of our people. Our nation’s highest challenge is to create a democracy that truly empowers people of all backgrounds, so that we all have a say in setting the policies that shape opportunity and provide for our common future. To help America meet that challenge, Demos is working to reduce both political and economic inequality, deploying original research, advocacy, litigation, and strategic communications to create the America the people deserve. About U.S. PIRG U.S. PIRG, the federation of state Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs), stands up to powerful special interests on behalf of the American public, working to win concrete results for our health and our well-being. With a strong network of researchers, advocates, organizers and students in state capitals across the country, we take on the special interests on issues such as product safety, public health, political corruption, tax and budget reform and consumer protection, where these interests stand in the way of reform and progress. demos.org Media Contact 220 Fifth Avenue, 2nd Fl. [email protected] New York, NY 10001 212.633.1405 ext. -

The New Democrat 2 May 2019

TThhee NNeeww DDeemmooccrraatt A Publication of the Peninsula Democratic Coalition (PDC) May 2019 Anna Eshoo’s Third Annual Mark Your Activist Summit Calendar! by Mary McVey Gill Friday, May 17, 2019 The Santa Clara County Democratic Party presents its 28th Annual Democratic Victory Dinner Celebrate the Year of At Congresswoman Anna Eshoo’s (CD-18) Activist Summit on April 17 at the Crown Plaza Hotel, Anna thanked all the activists Victorious Women! for their dedication and effectiveness and gave a brief history of some successful resist events since Trump’s 2016 election: the largest Women’s March in US history in January, 2017; Conor Hayes Mansion Lamb’s race (He knew about Anna because of all the work her constituents did to elect him!); the election of the most diverse 200 Edenvale Avenue, San Jose House with the most women in the 2018 Midterms. She said California is playing a prominent role in House oversight and General No-Host Reception 5:30-7:00 PM investigation committees, including three House committees with chairs from California: Adam Schiff, CD-28, Intelligence; Mark Dinner and Program 7:00-9:00 PM Takano, CD-48, Veterans Affairs, and Zoe Lofgren, CD-19, House Administration. Also, 21 CA Dems are chairs of subcommittees, including Anna who chairs the House Sub-committee on Health). Keynote Speaker: Anna informed us of the chaos in Washington, D.C. Because of unfilled positions, if you call an agency, chances are no one California Lieutenant will answer the phone. Recently, on a return flight to CA, Presidential Historian Michael Beschloss told Anna that it will Governor take 8-10 years for our country to repair the damage caused by Eleni Kounalakis the Trump Administration. -

Shepersisted Women, Politics & Power in the New Media World

#SHEPERSISTED WOMEN, POLITICS & POWER IN THE NEW MEDIA WORLD LUCINA DI MECO Global Fellow, The Wilson Center | Fall 2019 #SHEPERSISTED. WOMEN, POLITICS & POWER IN THE NEW MEDIA WORLD Lucina Di Meco Lucina Di Meco is a senior expert, advocate Magazine and New America, among others. and writer on women’s leadership and Lucina has a Magna Cum Laude in Political gender equality. She’s a Global Fellow at Science from the University of Turin (Italy), a The Wilson Center, where she researches Master in Development Economics from the women’s leadership in public service, as well University of East Anglia (UK), a Diploma as the Senior Director of Girls’ Education at in Gender Studies from the Facultad Room to Read, an international nonprofit Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales promoting gender equality through (FLACSO) in Mexico and is a Harvard education. Throughout her career, Lucina Women and Power Alumna. Lucina is also has worked in various capacities for a wide the co-founder of The Gender Breakfast, a range of international nonprofits (including network of gender equality experts based in Vital Voices, International IDEA, the the San Francisco Bay Area and serves on the Westminster Foundation for Democracy), Advisory Board of FundHer, an organization three UN agencies (UN Women, UNDP dedicated to electing progressive women to and UNIDO) and the OECD. She has State legislatures. written for The Hill, The Huffington Post, Ms -2 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION & METHODOLOGY ..........................................................................5 I. A WOMAN POLITICIAN: GENDERED MEDIA FRAMES ON WOMEN & POWER ....................................8 Global Patters and Regional Specificities in the Media Coverage of Women in Politics ....................................................................................................... -

HILLARY CLINTON's 2016 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN in PHILADELPHIA's LATINO COMMUNITY a Disser

COMMUNICATION AND THE BODY POLITIC: HILLARY CLINTON’S 2016 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN IN PHILADELPHIA'S LATINO COMMUNITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Juan S. Larrosa-Fuentes May 2018 Examining Committee Members: Nancy Morris, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Patrick Murphy, Media and Communication Brian Creech, Media and Communication Sandra L. Suárez, External Member, Political Science i ABSTRACT This dissertation contains a qualitative case study of how Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate, and her staff, created communication systems to contact Latinos during the 2016 presidential campaign and how these systems operated in Northeast Philadelphia. Three research questions guided these observations: How was political communication produced, disseminated, and decoded through interpersonal, mass, and digital communication by the Democratic candidate, her Latino communication staff, and Northeast Philadelphia Latino residents during the 2016 presidential campaign? What were the functions, norms, and values that structured the political communication systems among the Democratic candidate, her Latino communication staff, and Northeast Philadelphia Latino residents? What were the power relations that informed the interactions between the Democratic candidate, her Latino communication staff, and Northeast Philadelphia Latino residents in the political communication system? The dissertation employs the Political Communication Systems Model, a toolkit to observe and theorize on political communication. Under the grounded theory umbrella, two methods were used to collect data. First, Clinton’s mediated campaign communication was monitored. Second, I worked as a volunteer in a field operations office that Clinton opened in Philadelphia and performed a participant observation. Clinton built a political communication machine to produce a campaign that used a hybrid media system.