Team Payroll, Pitcher and Hitter Payrolls and Team Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Fans Split on Proposed Changes to the Game; Atlanta Braves Still America's Favorite Team

The Harris Poll r THE HARRIS POLL 1993 #37 For release: Monday, July 26, 1993 BASEBALL FANS SPLIT ON PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE GAME; ATLANTA BRAVES STILL AMERICA'S FAVORITE TEAM by Humphrey Taylor As major league baseball plans to reconfigure itself for the future, fans are split on the major proposed changes, according to the latest nationwide Harris Poll of 1,253 adults, 501 of whom are baseball fans, surveyed between June 24 and 29. Two-thirds of baseball fans (65 percent) support a limited schedule of games between American and National League teams during the regular season, but by a 54-44 percent margin, fans oppose increasing the number of teams advancing to post-season play from four to eight. Inter-league play, which receives the support of a 65-32 percent majority overall, gets the most support in the West, among those under 25 and Hispanics. Easterners, who appear to be baseball's most conservative fans, are the least supportive of inter-league play and the most opposed to expanding the playoffs. Narrow majorities of Southerners, L Westerners and African-Americans, on the other hand, support having more teams in the playoffs. Thirty-eight percent of the adults surveyed report following major league baseball. Most of these fans are serious students of the game, with just over half of fans (52 percent) reporting that they watch more than 20 baseball games a year on television or in person. While 10 percent of them feel there is too much baseball on television and 20 percent too little, fully 69 percent say the right amount of games are televised. -

Name of the Game: Do Statistics Confirm the Labels of Professional Baseball Eras?

NAME OF THE GAME: DO STATISTICS CONFIRM THE LABELS OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ERAS? by Mitchell T. Woltring A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Leisure and Sport Management Middle Tennessee State University May 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Colby Jubenville Dr. Steven Estes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not be where I am if not for support I have received from many important people. First and foremost, I would like thank my wife, Sarah Woltring, for believing in me and supporting me in an incalculable manner. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Julie Woltring, for always supporting and encouraging me to make myself a better person. I would be remiss to not personally thank Dr. Colby Jubenville and the entire Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Without Dr. Jubenville convincing me that MTSU was the place where I needed to come in order to thrive, I would not be in the position I am now. Furthermore, thank you to Dr. Elroy Sullivan for helping me run and understand the statistical analyses. Without your help I would not have been able to undertake the study at hand. Last, but certainly not least, thank you to all my family and friends, which are far too many to name. You have all helped shape me into the person I am and have played an integral role in my life. ii ABSTRACT A game defined and measured by hitting and pitching performances, baseball exists as the most statistical of all sports (Albert, 2003, p. -

Team Payroll Versus Performance in Professional Sports: Is Increased Spending Associated with Greater Success?

Team Payroll Versus Performance in Professional Sports: Is Increased Spending Associated with Greater Success? Grant Shorin Professor Peter S. Arcidiacono, Faculty Advisor Professor Kent P. Kimbrough, Seminar Advisor Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2017 Grant graduated with High Distinction in Economics and a minor in Statistical Science in May 2017. Following graduation, he will be working in San Francisco as an Analyst at Altman Vilandrie & Company, a strategy consulting group that focuses on the telecom, media, and technology sectors. He can be contacted at [email protected]. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Peter Arcidiacono, for his valuable guidance. I would also like to acknowledge my honors seminar instructor, Kent Kimbrough, for his continued support and feedback. Lastly, I would like to recognize my honors seminar classmates for their helpful comments throughout the year. 2 Abstract Professional sports are a billion-dollar industry, with player salaries accounting for the largest expenditure. Comparing results between the four major North American leagues (MLB, NBA, NHL, and NFL) and examining data from 1995 through 2015, this paper seeks to answer the following question: do teams that have higher payrolls achieve greater success, as measured by their regular season, postseason, and financial performance? Multiple data visualizations highlight unique relationships across the three dimensions and between each sport, while subsequent empirical analysis supports these findings. After standardizing payroll values and using a fixed effects model to control for team-specific factors, this paper finds that higher payroll spending is associated with an increase in regular season winning percentage in all sports (but is less meaningful in the NFL), a substantial rise in the likelihood of winning the championship in the NBA and NHL, and a lower operating income in all sports. -

Kyle Schwarber, of – 1St Rd Draft 2014 • Ben Zobrist, LF – Free Agent 2016 • Addison Russell, SS – Trade, 2014 • Justin Heyward, of – Free Agent 2016 Jake Arrieta

The 2016 Chicago Cubs Agenda •The Cubs: 1900 – 2008 •2009 – The Ricketts Family buys the Team •The 2016 World Series Chicago Cubs Winning Percentage by Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .618 .533 .535 .569 .471 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .434 .442 .474 .480 .468 2001-10 11-17 Total .504 .497 .512 Cubs Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 2 WS/4 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 3 Pnt 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 0 0 2 Div 0 2001-10 11-17 Total 3 Div 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 3 WS/11 Pnt/7 Div Cubs Cardinals Head to Head Record Over Time Cubs 1221 – Cardinals 1161 150 Cubs Cumulative wins over the years 100 50 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Cubs – Cardinals: Championship Totals 20 15 10 5 0 Cubs Cardinals Wild Cards Division Titles Penants World Series Titles Both Teams Suffer a Common (Bad) Fate Cubs White Sox • Great teams from 1901-1919 • Great teams from 1901-1919 • 1901-2017: 9062-8867 (.509) • 1901-2017: 9149-9026 (.503) • Hall of Famers: 16 • Hall of Famers: 13 • Largest crowds in town for ~80 years • Largest crowds in town ~40 years • 11 Pennants / 3 WS • 6 Pennants / 3 WS • WS: 1906, 1908, 2016 (108 yrs) • WS: 1906, 1917, 2005 (88 yrs) Both Teams’ Fans Know How to Suffer • "If there is any justice in the world, to be a White Sox fan frees a man from any other form of penance." - Bill Veeck, Jr. -

At Miami Marlins (41-46) RHP Brandon Mccarthy (6-3, 3.12) Vs

LOS ANGELES DODGERS (61-29) at Miami Marlins (41-46) RHP Brandon McCarthy (6-3, 3.12) vs. RHP Dan Straily (7-4, 3.31) Friday, July 14, 2017 | 7:10 p.m. PT | Marlins Park | Miami, FL Game 91 | Road Game 41 (22-18) | Night Game 64 (42-21) TV: SportsNet LA, SNLA Spanish | Radio: AM 570 (Eng.); 1020 AM (Span) BACK TO OUR REGULAR PROGRAMMING: The Dodgers MATCHUP vs. MARLINS st rd will kick off the official “second-half” of the season tonight playing Dodgers: 1 , NL West (7.5 GA) Marlins: 3 , NL East (10.5 GB) All-Time: LA leads series, 100-86 (9-7 at Marlins Park) the first of three with the NL East’s Miami Marlins. Los Angeles 2017: LA leads series, 3-1 (3-1 at Dodger Stadium) comes in red hot, having won six consecutive games and 26 of 30 May 18 @LA: W, 7-2 W: Ryu L: Volquez S: Jansen since June 7, giving the Dodgers the best record in the Major May 19 @LA: W, 7-2 W: Wood L:Nicolino Leagues. According to Elias, the Dodgers became just the fourth May 20 @LA: L, 6-10 W: Straily L: Urías team in the last 40 years to win 60 games before the All-Star Break May 21 @LA: W, 6-3 W: McCarthy L: Worley and it is the second time in the last 40 seasons that they became the TURNER TIME: Dodger All-Star third baseman Justin Turner first team to reach 60-wins, joining the 2009 team. -

The Interaction Between Baseball Attendance and Winning Percentage: a VAR Analysis

The Interaction between Baseball Attendance and Winning Percentage: A VAR Analysis Michael C. Davis Department of Economics University of Missouri-Rolla 101 Harris Hall 1870 Miner Circle Rolla, MO 65409-1250 [email protected] 573-341-6959 The author would like to thank Skip Sauer, Brad Humphreys and Kim Henthorn for their helpful comments. 1 The Interaction between Baseball Attendance and Winning Percentage: A VAR Analysis 2 ABSTRACT This study examines the importance of team success for attendance for major league baseball teams. Winning and attendance go together for most baseball teams, but the direction of causation is not obvious. Winning could lead to greater attendance as fans want to see a winner, while an increase in attendance could lead to greater winning as teams’ have greater resources to spend on salaries. This study finds that the direction of causation runs from team success to greater attendance, and that a sudden increase in fans does not lead to additional winning in the future. A secondary result suggests that exogenous shocks to attendance have replicating effects on attendance as well. Key Words: baseball, attendance, vector autoregression 3 It is only natural that sports fans would want to support a strong performance on the field and attend more games of a more successful team. The quality of play will be higher for a good team, the home team will be more likely to win and the atmosphere will be more enjoyable since other fans will be more excited by a good team. A successful season will also lead to increases in attendance during the following years as the momentum of the previous success draws in more fans through a bandwagon effect. -

Pittsburgh Pirates (67-61) Vs

www.CubsPressbox.com * [email protected] * 773-404-4191 * @Cubs * 1060 W. Addison St., Chicago, IL 60613 Pittsburgh Pirates (67-61) vs. Chicago Cubs (82-47) Information © 2016 Chicago Cubs Media Relations Office August 29, 2016 … Wrigley Field … Game No. 130 … Home Game No. 65 LHP Steven Brault (0-1, 3.60) vs. RHP Jake Arrieta (16-5, 2.62) HOME, SWEET HOME: The Chicago Cubs tonight begin a seven-game homestand CUBS VS. PIRATES with the first of three games against the Pittsburgh Pirates following a 5-4, 10-day CUBS RECORD West Coast trip at Colorado (1-2), San Diego (3-0) and Los Angeles (1-2) … following The Cubs and Pirates this regular season this Pirates series, the Cubs will host the Giants for four games. 2016 Overall: ......................................... 82-47 play 19 games spanning six series … Chicago © At 82-47, the Cubs own the best record in all of baseball, 6.0 games better than At Wrigley Field: .................................. 45-19 is 13-5 in its last 18 games against the the next closest club (Texas Rangers, 77-54) … the Cubs have won 23 of their On the Road: ........................................ 37-28 Pirates … this is Chicago’s first meeting last 30 games. April: ................................................... 17-5 against the Pirates since closing out the first © The Cubs have gone 30-12 (.714) in their last 42 games starting July 10, also the May:.................................................. 18-10 half with three games in Pittsburgh (1-2) … best record in all of baseball in that span … the Cubs have more than doubled June .................................................. 16-12 the teams previously played at Wrigley their lead in the N.L. -

Ital Ia Na Mericanbaseballi Nd Uc Tees Inthenational Baseball Halloffame

Poster Layout #2 2016_Layout 1 3/15/16 12:23 PM Page 1 i c a n B a s e n A m e r Poster Two b a l l I n I t a l i a d u c t e e s Phil Rizzuto Ron Santo Mike Piazza (1917-2007) Shortstop (1940- ) Third Baseman John Smoltz (1968- ) Catcher Phil (Scooter) Rizzuto joined the (1967- ) Pitcher Yankee Dynasty and played his Ronald Edward Santo, February Ernie Lombardi Michael Joseph Piazza, born Sep - 25, 1940 - December 3, 2010, was Joseph “Joe” Torre (1908-1977) Catcher entire career with them (1941-42 and John Andrew Smoltz, born May 15, tember 4, 1968, played MLB from 1946-56). He helped the Yankees a Major League Baseball third 1967, played MLB from 1988 to (1940- ) Manager Ernie Lombardi was slow afoot, but 1992-2007. A 12-time All-Star and win seven of nine World Series baseman that played for the 2009. An eight-time All-Star, he didn't let his lack of speed deter 10-time Silver Slugger Award win - during his 13 seasons. Scooter was Chicago Cubs from 1960 through Smoltz helped propel Atlanta to Joseph Paul "Joe" Torre, born July him. In his 17-year career, he ner as a catcher, Piazza produced a durable and deft shortstop, skilled 1973 and the Chicago White Sox in perennial pennant contention in 18, 1940, is ranked fifth all-time in compiled a .306 batting average strong offensive numbers at his po - bunter and enthusiastic base runner 1974. Santo was an All-Star for the 1990s, highlighted by a cham - MLB history with 2,326 wins as a and was recognized as a powerful sition. -

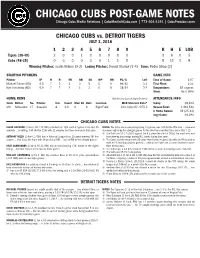

CHICAGO CUBS POST-GAME NOTES Chicago Cubs Media Relations | [email protected] | 773-404-4191 | Cubspressbox.Com

CHICAGO CUBS POST-GAME NOTES Chicago Cubs Media Relations | [email protected] | 773-404-4191 | CubsPressbox.com CHICAGO CUBS vs. DETROIT TIGERS JULY 3, 2018 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E LOB Tigers (38-49) 2 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 8 0 5 Cubs (48-35) 0 0 0 0 3 0 1 1 X 5 11 1 8 Winning Pitcher: Justin Wilson (3-2) Losing Pitcher: Daniel Stumpf (1-4) Save: Pedro Strop (2) STARTING PITCHERS GAME INFO Pitcher IP H R ER BB SO WP HR PC/S Left Time of Game: 2:57 Michael Fulmer (ND) 6.0 7 3 3 3 5 0 0 99/62 3-3 First Pitch: 1:22 Kyle Hendricks (ND) 5.0 7 3 3 1 2 0 0 78/54 3-3 Temperature: 83 degrees Wind: NE 6 MPH HOME RUNS *Exit Velocity/Launch Angle/Distance ATTENDANCE INFO Team Batter No. Pitcher Inn. Count Men On Outs Location MLB Statcast Data* Today: 38,424 CHI Schwarber 17 Saupold 8 1-0 0 0 Right Field 103 mph/25°/375 ft Season Total: 1,493,512 # Home Games: 39 (25-14) Avg/Game: 38,295 CHICAGO CUBS NOTES JASON HEYWARD (2-for-4, 2B, 2 R, RBI) collected his 13th multi-hit game in his last 30 NOTES: The Cubs are a season-high tying 13 games over .500 for the fifth time ... have won contests ... is batting .349 (44-for-126) with 12 doubles and three homers in that span. -

What Contributing Factors Play the Most Significant Roles in Increasing the Winning Percentage of a Major League Baseball Team?

Cost of Winning: What contributing factors play the most significant roles in increasing the winning percentage of a major league baseball team? The Honors Program Senior Capstone Project Student’s Name: Patrick Tartaro Faculty Sponsor: Betty Yobaccio April 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Literary Review ......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodolgy ............................................................................................................................. 10 Results ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………….21 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………28 References ............................................................................................................................... 30 Cost of Winning: What contributing factors play the most significant roles in increasing the winning percentage of a major league baseball team? Patrick Tartaro ABSTRACT Over the past decade, discussions of competition disparity in Major League Baseball have been brought to the forefront of many debates regarding the sport. The belief -

The Determinants of Mlb Franchise Value

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Winning Off Theield F : The etD erminants of MLB Franchise Value David F. Ulrich Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Ulrich, David F., "Winning Off Theie F ld: The eD terminants of MLB Franchise Value" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 292. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/292 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE WINNING OFF THE FIELD: THE DETERMINANTS OF MLB FRANCHISE VALUE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR DARREN FILSON AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY DAVID ULRICH FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2011 NOVEMEBER 23, 2011 Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv Abstract v I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. SURVEY OF LITERATURE 2 Sales Prices vs. Forbes’ Published Estimates 3 Effect of Team’s Location and Stadium 4 Growth of Team Values 5 Tax Shields and Incentives 5 III. DESCRIPTION OF DATA 6 Forbes Magazine Estimates 7 Team Marketing Report Data 10 Census Data 10 Facilities Data 10 Additional Data 11 Shortcomings of the Data 11 IV. DATA SUMMARY 12 V. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 13 Basic Model 15 Revenues, Winning and “Moneyball” 15 Attendance and Pricing 19 Television and Media 20 Ballpark and Market 21 VI. CONCLUSION ` 22 VII. DATA APPENDIX 25 VIII. REFERENCES 27 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Darren Filson, Mr. Bob Graziano and Alex Sunderland for their insight, guidance and support during the development and completion of this thesis. -

St. Louis Cardinals (2-2) at Miami Marlins (1-3) Game No

St. Louis Cardinals (2-2) at Miami Marlins (1-3) Game No. 5 • Road Game No. 5 • loanDepot park • Tuesday, April 6, 2021 RHP John Gant (0-3, 2.40 in 2020) vs. RHP Sandy Alcantara (0-0, 0.00) RECENT REDBIRDS: The St. Louis Cardinals continue their season-opening six- RECORD BREAKDOWN game road trip with the second game of a three-game series with the Miami CARDINALS vs. MARLINS All-Time Overall ......... 10,169-9,658 Marlins at the newly-named loanDepot park ... St. Louis (2-2) begins the day in All-Time (1993-2021) ............................. 119-81 3rd place in the NL Central, 1.0 game back of 1st place Cincinnati and Chicago. 2021 Overall ................................2-2 in St. Louis (1993-2019) ................................... 55-45 Under Mike Shildt ...............164-129 ‘BEACH BIRDS: Since the Marlins joined MLB as an expansion team in 1993, the at Busch Stadium II (1966-2005) .................. 32-25 Busch Stadium ........................... n/a Cardinals own the Majors’ best win pct. (63-36, .636) of any team to visit Miami, at Busch Stadium III (2006-19) ..................... 24-20 On the Road ................................2-2 while their .667 win pct. (18-9) at loan Depot park since it opened in 2012 trails in Miami (1993-2021) .............................63-36 Day ..............................................1-2 only Tampa Bay (18-7, .720) for teams who play in Miami every season ... St. at Sun Life Stadium (1993-2011) .................. 45-27 Night ............................................1-0 Louis also owned the best win pct. at Sun Life Stadium (.625, 45-27) for teams at loanDepot park (2012-21) ................... 18-9 Spring.........................................