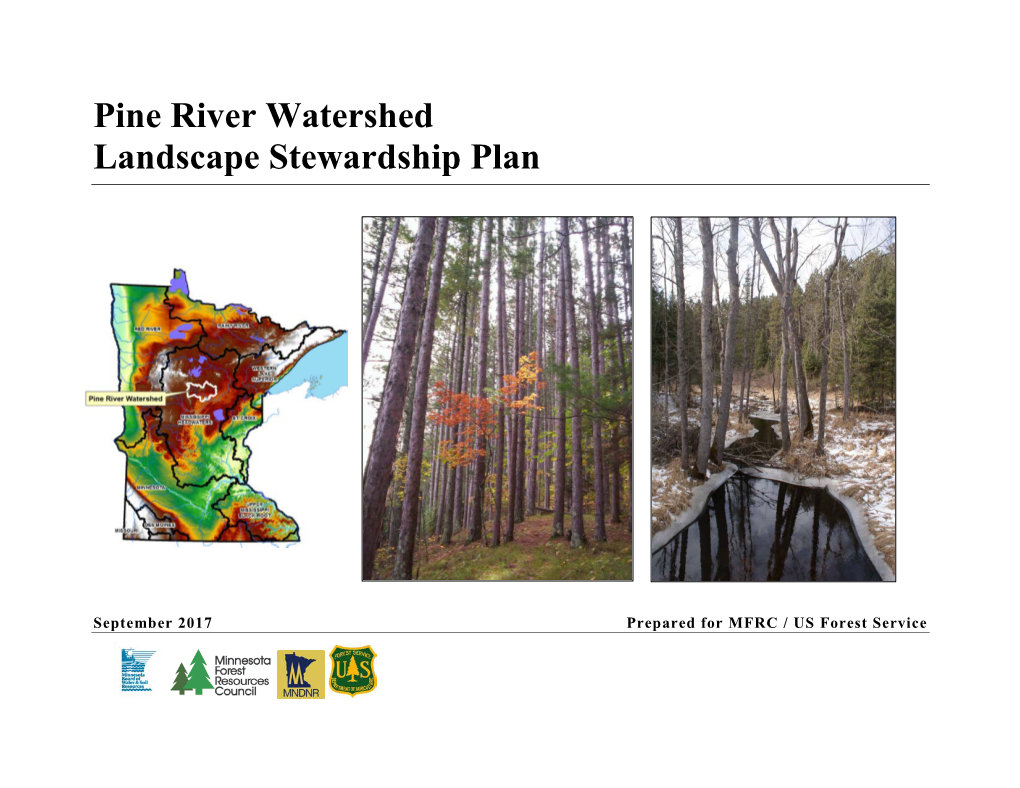

Pine River Watershed Landscape Stewardship Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATVAM News - June 14, 2018 Newsletter of the ATV Association of Minnesota (Est

ATVAM News - June 14, 2018 Newsletter of the ATV Association of Minnesota (Est. 1983) Send us your comments, club news, photos and article ideas. Email them to: [email protected]. Forward this email to club partners and business sponsors if they aren't ATVAM members already. ATVAM members should be receiving this newsletter and MN OffRoad magazine. Let us know if you're not. Please note: Send member renewals to new mailing address: ATVAM, PO Box 300, Stacy, MN 55079 E-newsletters are now archived on atvam.org to refer back to on topics. In This e-Newsletter: -ATV Legislative Update For Session Just Ended -DNR Moves "Free Wheelin' Weekend" To September -Side-by-Sides: 10 Years In The Making -Ribbon-Cutting Held For New ATV Park In SW Minnesota -Resources For Parents Of Children Who Want To Ride -Club Rides & Work Days Coming Up -Thanks For Supporting ATV Minnesota ATVAM Legislative Update For Session Just Ended By Ray Bohn & Tom Hackbarth ATVAM Lobbyists May 28, 2018 (also printed in the June/July Minnesota OffRoad magazine) While ATVAM initiatives faired very well on paper in the 2018 Legislative Session, because of the inability of the legislative majority and the governor to come to compromises on big ticket items, pretty much all was lost to the governor's veto of the Omnibus Supplemental Finance Bill. With a large percentage of policy language and all finance legislation placed in one large bill (990 pages - -- SF3656) instead of in singular subjects, it placed the entire bill in jeopardy of a veto on any single policy issue within the bill. -

Brainerd Area

R34W R33W R32W R31W R30W R0W R29W R0W R28W R27W R26W R25W R25W R27W R26W R25W R24W 95°0'0"W 94°55'0"W 94°50'0"W 94°45'0"W 94°40'0"W 94°35'0"W 94°30'0"W 94°25'0"W 94°20'0"W 94°15'0"W 94°10'0"W 94°5'0"W 94°0'0"W 93°55'0"W 93°50'0"W 93°45'0"W 93°40'0"W 93°35'0"W 93°30'0"W 93°25'0"W 93°20'0"W Steamboat River Blandin Dam Trout 1 6 1 6 1 6 6 Sugar Point Bog 1 6 1 6 Poole Bay 47°13'55"N Little Bear Creek 1 6 La Prairie Laporte Bear River 1 159 Buffalo Creek Garfield Swamp Goose Vermillion River Meyers Bay 146 501 Rice 190 Lake George 320 Battleground State Forest Leighton Brook Prairie RiverGunn 47°11'55"N MN12 304 326 Rice 170 George 219 36 31 Sugar Bay GPZ T55N 36 31 36 31 36 Elevenmile Corner 119 Steamboat Bay 47°11'55"N Bemidji Area Kabekona RiverGulch Creek Salter Bay 129 Skunk Brook Sugar Brook King Bay 412 Boy Bay Boy River 1 6 100 T143N 1 6 1 6 1 Dan Dick Creek Pokegama Blackberry 47°9'55"N 220 212 ¤£2 36 31 Y49 Boy River Kabekona Benedict 36 36 31 Welshes Bay 36 31 Sucker Branch 36 31 36 31 Sherry Arm Bay 47°9'55"N 36 31 Philbin 1 36 31 Sugar 6 Kabekona River 6 36 Siseebakwet 1 6 1 6 1 Traders Bay Leech EWM 1 6 Wendigo Arm Bay 47°7'55"N 1 6 1 6 9995 Kabekona Bay 1 Remer State Forest 370 T54N Baker 295 Deer River Area 47°7'55"N Big Thunder Peak Agency Bay Smith Creek B1 B2 Onigum Headquarters Bay Tobique 36 31 36 31 47°5'55"N Walker Walker Bay 36 31 36 T142N Boy Golden Anniversary State Forest 416 412 Loon Lake Dam 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 47°5'55"N 155 North Fork Willow River Kaylor Fishpond Dam Brevik Swift River 259 36 31 261 Uram Bay Emmaville -

11.0 Rec Areas Sandp

North Dakota Pipeline Company LLC Minnesota Environmental Information Report Routing Permit Docket No. PL-6668/PPL-13-474 Revised January 2014 Certificate of Need Docket No. PL-6668/CN-13-473 Page 11-1 11.0 FEDERAL, STATE, AND COUNTY RECREATIONAL AREAS 11.1 EXISTING DESIGNATED RECREATIONAL AREAS The preferred route will not cross any national parks, national forests, national landmarks, wilderness areas, wildlife refuges, waterfowl production areas, or national wildlife management areas. However, the Project will cross a federally designated trail, state and county forests, county parks, state WMAs and AMAs, state-designated trails, designated scenic byways, and state-designated water trails as discussed in the following subsections. 11.1.1 Federally Designated Recreation Areas and Trails The preferred route will not cross federal recreation areas. However, the North Country Trail, a National Scenic Trail, will be crossed at MP 417.6 in Hubbard County. NDPC initiated consultation with NPS and the North Country Trail Association regarding this crossing. Because the trail is on county-owned land, NDPC will also consult with Hubbard County to minimize impacts on the trail. As discussed in Section 9.2, the preferred route will cross four Minnesota rivers that are listed on the NRI. These rivers are the Red Lake River (MP 305.7 and 325.7) in Polk County, the Clearwater River (MP 388.3) in Clearwater County, the Moose River (MP 511.4, MP 512.6, MP 513.5 and MP 513.8) in Cass and Aitkin counties, and the Willow River in Aitkin County (MP 531.2). None of these are federally designated as National Wild and Scenic River. -

1~11~~~~11Im~11M1~Mmm111111111111113 0307 00061 8069

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE LIBRARY ~ SD428.A2 M6 1986 -1~11~~~~11im~11m1~mmm111111111111113 0307 00061 8069 0 428 , A. M6 1 9 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) State Forest Recreation Areas Minnesota's 56 state forests contain over 3.2 million acres of state owned lands which are administered by the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry. State forest lands are managed to produce timber and other forest crops, provide outdoor recreation, protect watershed, and perpetuate rare and distinctive species of flora and fauna. State forests are multiple use areas that are managed to provide a sustained yield of renewable resources, while maintaining or improving the quality of the forest. Minnesota's state forests provide unlimited opportunities for outdoor recreationists to pursue a variety of outdoor activities. Berry picking, mushroom hunting, wildflower identification, nature photography and hunting are just a few of the unstructured outdoor activities which can be accommodated in state forests. For people who prefer a more structured form of recreation, Minnesota's state forests contain over 50 campgrounds, most located on lakes or canoe routes. State forest campgrounds are of the primitive type designed to furnish only the basic needs of individuals who camp for the enjoyment of the outdoors. Each campsite consists of a cleared area, fireplace and table. In addition, pit toilets, garbage cans and drinking water may be provided. -

Chengwatana State Forest

Chengwatana State Forest Kettle St. Croix State Park Boundary Chengwatana State Forest Boundary St. Croix Is It Trespassing? Half StateRiver Park On private land, the simple and best answer is, Ask First! Signs are posted by the landowners, Through (vehicle permit required) and they will state, No Trespassing, or similar words in two-inch letters and the signature or name and telephone number of the landowner, lessee, or manager. There can be civil and criminal penalties for violation of the trespass laws. Snowmobiles only Civil penalties start at $50 for first offense and north of gate range up to $500 and 14 128 loss of license or Half registration for a third Through offense within three Trail years. All conservation Entrance to the Forest and peace officers enforce watch for signs! 10 Rivers trespass laws. End Rivers 10 Chengwatana Rd. End Evergreen Road TO FOREST Segment Two Rivers 10 Chengwatana Road Ledge Snake Trail See Map Right Loop Snake River Campground To Pine City Snake Bit 3 Miles River 8 118 Boundary Redhorse See Map Inner Trail 117 Below Left Two Grouse State Rivers 218 0 1 2 3 3 Information Station Scale in Miles National Park Service 70 Trail River River Road Chengwatana To Rock Creek 2 Miles Eagle 2 WISCONSIN Rock Trail Grouse Marsh Munger 104 Wildlife Management Ledge Area Rambler 104 Map Legend Stevens WISCONSIN Creek Croix Croix Parking Pine Co. Hawk Chisago Co. Canoe Camping St. North Rock Camping Willard Creek Boat Access © 2008, State of Minnesota 3 Department of Natural Resources St. Carry-in Access Old R.R Bridge Shelter 5 Gate 19 SnakeSnake RiverRiver CampgroundCampground 21 Campground Symbols 23 20 Parking Willard860 25 17 22 18 Hiking/Skiing Trails 850 24 15 Vault Toilets 26 13 16 6 14 8 Drinking Water Rush City ATV/OHM Trails 12 10 7 Rush Ferry 840 Snake 9 4 Picnic Area Munger 2 ATV/OHM Trails (open to Class 2 ATVs) 11 5 810 3 River 830 1 49 State Forest Road (open to all motor vehicles in this forest, unless posted closed) 820 Snowmobile Trails (Dec. -

HOUSE RESEARCH Bill Summary

HOUSE RESEARCH Bill Summary FILE NUMBER: H.F. 810 DATE: May 8, 2003 Version: Second Engrossment Authors: Howes and others Subject: State land acquisition Analyst: Kathy Novak 651-296-9253 This publication can be made available in alternative formats upon request. Please call 651-296-6753 (voice); or the Minnesota State Relay Service at 1-800-627-3529 (TTY) for assistance. Summaries are also available on our website at: www.house.mn/hrd. Overview This bill provides for acquisition, sale, deletion, exchange and conveyance of public land. Section 1 Names, acquisition; administration. Provides that tax-forfeited land located inside a state recreation area is withdrawn from sale and is transferred to the commissioner of natural resources. The commissioner must provide a certificate of acceptance for the state. 2 Creation; urban whitewater trail. Changes the definition of the trail. 3 Composition of system. Adds the Lake Superior water trail and the Mississippi whitewater trail to the definition of the outdoor recreation system. 4 Mineral coordinating committee. Establishes a ten-member committee to plan for diversified mineral development consisting of seven named members and three appointed by the governor. The committee is chaired by the commissioner of natural resources who must also provide staff. The committee expires June 30, 2007. 5 Greenleaf lake state park. Establishes a state park in Meeker county and describes the park lands. 6 Additions to state parks. Adds specified lands to the following state parks. Subd. 1. Fort Snelling state park, Ramsey, Hennepin, and Dakota counties. Subd. 2. Lake Bemidji state park, Beltrami county. Subd. 3. Tettegouche state park, Lake county. -

L-SOHC Request for Funding Form 1 Request for Funding Form Lessard

Request for Funding Form Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council Fiscal Year 2011 Program or Project Title: #30 Accelerated Forest Wildlife Habitat Program Date: November 2, 2009 Manager’s Name: Cynthia Osmundson Title: Forest Wildlife Program Consultant Division of Fish and Wildlife, DNR Mailing Address: 500 Lafayette Rd, St. Paul, MN. 55155 Telephone: (651) 259-5190 Fax: (651) 297-4961 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: .dnr.state.mn. Council Out-Year Projections of Needs Funding Request Funds Requested ($000s) FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 Forest Habitat Enhancement and 7,180 Restoration Div. of Forestry Lands 4,161 Wildlife Management Areas 1,719 (WMAs) Scientific and Natural Areas 1,300 (SNAs Forest Habitat Acquisition 10,343 4,960 8,000 8,000 Outdoor Heritage Fund Totals 17,523 A. Summary Our program will increase populations of a variety of game and non-game wildlife species by protecting, restoring, and enhancing forest vegetation (habitats) on which wildlife depends. This program of on-the-ground forest conservation projects will amplify the wildlife value of forest communities on Department of Natural Resources (DNR) administered forestlands. Our forest restoration and enhancement management will treat 27,060 ac during this funding cycle. These activities are not conducted as part of the DNR’s commercial timber operations. Additionally, our program will acquire 2,219 ac of forestland that contributes to habitat complexes and other high priorities. Acquisitions focus on forestland for public hunting, and compatible outdoor uses consistent with the Outdoor L-SOHC Request for Funding Form 1 Recreation Act (M.S. -

Foot Hills State Forest Study

Outdoor Recreation Study of the Foot Hills Forest Area, Summer & Fall 2004 Outdoor Recreation Study of the Foot Hills Forest Area, Summer & Fall 2004 Foot Hills Forest Study Area 0 20406080100Miles No rth er n f ore st Bemidji reg # ion Moorhead Foot Hills # # Brainerd # Duluth St. Cloud # Minneapolis##St. Paul # Winona Mankato # # Rochester The Foot Hills outdoor recreation study was a cooperative research project of Cass County and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Report prepared by: Office of Management and Budget Services Minnesota Department of Natural Resources July 2005 2 2004 Foot Hills Outdoor Recreation Study CONTENTS Topic Page Summary . 4 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 11 Study results Visitor use quantities . 15 Visitor activities . 16 Visitor market areas . 19 Trip characteristics for public-entry visitors . 22 Experiences important to visitors when using Foot Hills . 26 Quality of visitor experience . 28 Visitor problems in the use of Foot Hills . 30 Support/opposition to Foot Hills management options . 36 Visitor-caused problems for adjacent landowners . 39 Demographics of public-entry visitors and adjacent landowners . 41 References . 44 Appendix A: Survey instrument for public-entry visitors . 45 Appendix B: Survey instrument for adjacent private landowners . 52 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources 3 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION The Foot Hills area is located in southern Cass County, near the periphery of Minnesota’s northern forest region. The area is one the first forest settings encountered when traveling to the northwoods from Minnesota’s primary population concentration in the greater Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. The area encompasses both the public forestland within the statutory boundaries of Foot Hills State Forest, and the Foot Hills Forest Study Area public forestland adjacent to the State Forest. -

State Forest Recreation Guide

Activities abound Camping in State www.mndnr.gov/state_forests in a state forest. Forests... Choose your fun: Your Way Minnesota There are four different ways of • Hiking camping in a state forest. State • Mountain biking 1. Individual Campsites- campsites designated for individuals or single Forest • Horseback riding families. The sites are designed to furnish • Geocaching only the basic needs of the camper. Most consist of a cleared area, fire ring, table, • Canoeing vault toilets, garbage cans, and drinking Recreation water. Campsites are all on a first-come, • Snowmobiling first-served basis. Fees are collected at the sites. Guide • Cross-County Skiing 2. Group Campsites- campsites designated • Biking for larger groups.The sites are designed to furnish only the basic needs of the • OHV riding camper. Most consist of a cleared area, • Camping fire ring, table, vault toilets, garbage cans, and drinking water. Group sites are all on • Fishing a first-come, first-served basis. Fees are collected at the sites. • Hunting 3. Horse Campsites- campsites where • Berry picking horses are allowed. The sites are designed to furnish only the basic needs of the • Birding camper. Most consist of a cleared area, fire ring, table, vault toilets, garbage cans, • Wildlife viewing and drinking water. In addition, these • Wildflower viewing campsites also may have picket lines and compost bins for manure disposal. The State Forest Recreation Guide is published by the Minnesota Department of Campsites are all on a first-come, first- Natural Resources, Division of Forestry, 500 Lafaytte Road, St.Paul, Mn 55155- 4039. Phone 651-259-5600. Written by Kim Lanahan-Lahti; Graphic Design by served basis. -

Minnesota Statutes 2018, Section 89.021

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2018 89.021 89.021 STATE FORESTS. Subdivision 1. Established. There are hereby established and reestablished as state forests, in accordance with the forest resource management policy and plan, all lands and waters now owned by the state or hereafter acquired by the state, excepting lands acquired for other specific purposes or tax-forfeited lands held in trust for the taxing districts unless incorporated therein as otherwise provided by law. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 1982 c 511 s 9; 1990 c 473 s 3,6 Subd. 1a. Boundaries designated. The commissioner of natural resources may acquire by gift or purchase land or interests in land adjacent to a state forest. The commissioner shall propose legislation to change the boundaries of established state forests for the acquisition of land adjacent to the state forests, provided that the lands meet the definition of forest land as defined in section 89.001, subdivision 4. History: 2011 c 3 s 3 Subd. 2. Badoura State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 1967 c 514 s 1; 1980 c 424; 2018 c 186 s 10 subd 1 Subd. 3. Battleground State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. 4. Bear Island State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 2016 c 154 s 15 subd 1 Subd. 5. Beltrami Island State Forest. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 2000 c 485 s 20 subd 1; 2004 c 262 art 2 s 14 Subd. 6. Big Fork State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. -

Mason's Minnesota Statutes 1927

1940 Supplement To Mason's Minnesota Statutes 1927 (1927 to 1940) (Superseding Mason s 1931, 1934, 1936 and 1938 Supplements) Containing the text of the acts of the 1929, 1931, 1933, 1935, 1937 and 1939 General Sessions, and the 1933-34,1935-36, 1936 and 1937 Special Sessions of the Legislature, both new and amendatory, and notes showing repeals, together with annotations from the various courts, state and federal, and the opinions of the Attorney General, construing the constitution, statutes, charters and court rules of Minnesota together with digest of all common law decisions. Edited by William H. Mason Assisted by The Publisher's Editorial Staff MASON PUBLISHING CO. SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA 1940 §6260-3 CH. 39—BOUNTIES AND REWARDS mal was killed, or, If the animal was killed in unor- killed, and date and place of the killing thereof-. (Act ganized territory, to the nearest town clerk in the Apr. 24, 1931, c. 309, §3; Apr. 14, 1939, c. 258, §3.) same county, and shall make and deliver to the town clerk a written statement of his claim under oath, in 6260-4. Certificate to be presented to county au- duplicate, describing the animal as adult or cub, as ditor.—The claimant shall produce both duplicates the case may be, specifying the time and place of the of the statement and certificate, together with the killing thereof by the claimant, and stating that he hide of each animal described therein, with scalp and did not on that occasion spare the life of any grey or ears intact, to the county auditor. -

Journal of the Senate EIGHTY-THIRD LEGISLATURE ______THIRTY-SIXTH DAY

STATE OF MINNESOTA Journal of the Senate EIGHTY-THIRD LEGISLATURE ________________ THIRTY-SIXTH DAY St. Paul, Minnesota, Thursday, April 10, 2003 The Senate met at 9:00 a.m. and was called to order by the President. CALL OF THE SENATE Senator Betzold imposed a call of the Senate. The Sergeant at Arms was instructed to bring in the absent members. Prayer was offered by the Chaplain, Pastor Scott T. Westphal. The roll was called, and the following Senators answered to their names: Anderson Gaither Larson Ortman Senjem Bachmann Hann LeClair Ourada Skoe Bakk Higgins Limmer Pappas Skoglund Belanger Hottinger Lourey Pariseau Solon Berglin Johnson, D.E. Marko Pogemiller Sparks Betzold Johnson, D.J. Marty Ranum Stumpf Chaudhary Jungbauer McGinn Reiter Tomassoni Cohen Kelley Metzen Rest Vickerman Day Kierlin Michel Robling Wergin Dibble Kiscaden Moua Rosen Wiger Dille Kleis Murphy Ruud Fischbach Knutson Neuville Sams Foley Kubly Nienow Saxhaug Frederickson Langseth Olson Scheid The President declared a quorum present. The reading of the Journal was dispensed with and the Journal, as printed and corrected, was approved. RECESS Senator Hottinger moved that the Senate do now recess subject to the call of the President. The motion prevailed. After a brief recess, the President called the Senate to order. CALL OF THE SENATE Senator Betzold imposed a call of the Senate. The Sergeant at Arms was instructed to bring in the absent members. 916 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE [36TH DAY EXECUTIVE AND OFFICIAL COMMUNICATIONS The following communications were received and referred to the committee indicated. April 4, 2003 The Honorable James P.