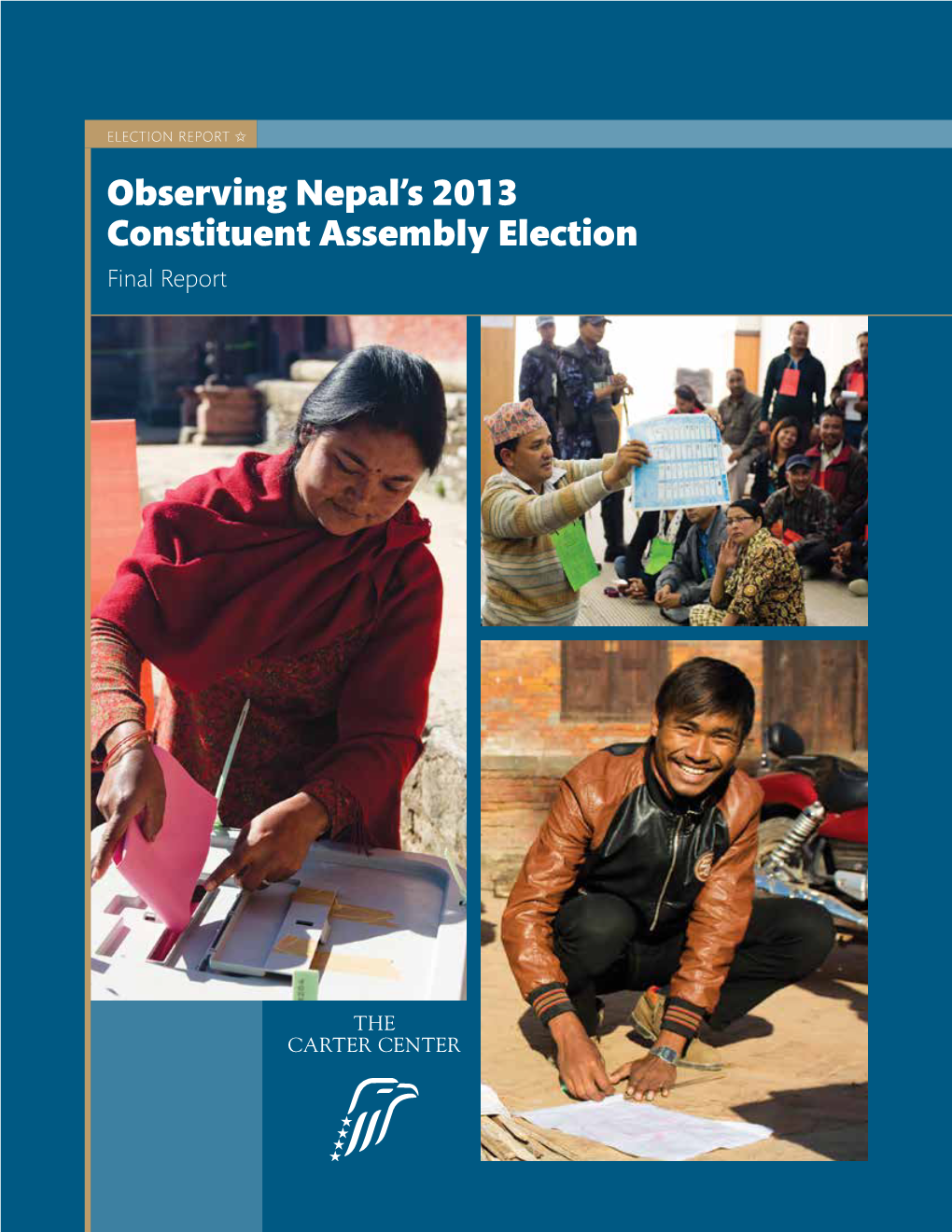

Observing Nepal's 2013 Constituent Assembly Election (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outbreak Situation Report 23 August 2009

Outbreak Situation Report 23 August 2009 Outbreak Situation Report 23 August 2009 This report has been prepared by the health cluster based on information collected from the MoHP, partners on the ground as well as district officials. Situation • As of 23rd August 2009, the cumulative number of treated and deaths since 1st May 2009 can be summarized as follows: Affected No.of Health No. of People District VDC Camp Treated Death No. Jajarkot 30 51 25476 153 Rukum 23 23 12705 48 Dolpa 7 7 501 7 Rolpa 9 6 664 6 Salyan 4 2 526 6 Dailekh 32 18 6842 25 Bajura 4 4 122 6 Dadeldhura 3 2 153 5 Doti 20 6 1344 10 Surkhet 17 9 4492 14 Kanchanpur 3 1 288 1 Pyuthan 3 2 250 2 Makwanpur 1 1 137 0 Dang 1 1 61 0 Achham 22 8 5396 21 Bajhang 2 1 757 7 Baitadi 16 2 443 8 Dhading 1 0 103 0 Kailali 8 3 89 4 Sarlahi 1 1 40 2 Total 206 148 58874 314 • Based on the epidemiological evidences, diarrheal outbreak has affected Jajarkot, Rukum, Dailekh, Surkhet, Accham and Bajhang. Close monitoring of other districts are on going by the EDCD, RHDs and DHOs. • Based on the findings of laboratory results on Antimicrobiological sensitivity test, the treatment protocol has been updated, shared with the EDCD and sent to the affected districts. • Samples are being tested in National Public Health Laboratory and 36% of total samples have shown the growth of Vibrio Cholerae 01 Tor Ogawa and remaining have shown the Enterotoxicogenic E Coli (LT and ST) and Aeromonas species. -

Nepal-India Think Tank Summit 2018 Opening Ceremony Session I

Summit Schedule Nepal-India Think Tank Summit 2018 Registration and Breakfast 8:00 AM- 9:00 AM 9:00 AM-10:00 AM Opening Ceremony Opening Remarks: Mr. Shyam KC, Research and Development Director, AIDIA Chair Remarks: Shri Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) Special Remarks: H.E. Manjeev Singh Puri, Ambassador of India to Nepal Keynote Speech: Shri Ram Madhav, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party and Director, India Foundation Special Guest Remarks: Hon'ble Mr. Matrika Prasad Yadav, Minister for Industry, Commerce & Supplies Special Address: Chief Guest Rt. Hon’ble Former Prime Minister of Nepal, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ Vote of Thanks: Mr. Sunil KC, Founder/CEO, Asian Institute and Diplomacy and International Affairs (AIDIA) Opening Session Brief Think Tank, as a shaper of various policy related questions, acts as a bridge between the world of idea and action. And it recommends best possible policy options to the government to meet the daunting challenges in the domestic and the international affairs. The session aims to locate the major role of the think tank in addressing the emerging foreign policy questions and the importance of cooperation between the think-tank of Nepal and India. 10:00 AM-11:30 AM Session I: Building Innovative Cooperation between Indo-Nepal Think Tank: The Partnership Chair Hon'ble Mr. Gagan Thapa, Member of Parliament, Nepali Congress Panelists: Prof. Dr Shambhu Ram Simkhada, Convener, CNI Think Tank, Former Permanent Representative of Nepal to the United Nations Major General Rajiv Narayanan, AVSM, VSM (Retd) Shri Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) Dr. -

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

The Right to Adequate Food in Nepal

Parallel Information: The Right to Adequate Food in Nepal Article 11, ICESCR FIAN Nepal August 2014, Kathmandu Imprint Published by: FIAN Nepal Kupondole, Lalitpur, P. O. Box: 11363 Nepal email: [email protected] Website: http://www.fiannepal.org FIAN International Willy-Brandt-Platz 5 69115 Heidelberg, Germany Email: [email protected] http://www.fian.org Edited by: Yubraj Koirala, Dip Magar, Basanta Adhikari, Sarba Raj Khadka, Tilak Adhikari, Ana Maria Suarez Franco, Sabine Pabst, Alison Graham Layout: Suman Piya Cover photo: A woman with a baby in her back, assisted by another girl are busy plucking up tender leaves/buds from a stinging nettle plant. People in some parts of Nepal, mainly in the rural areas of hills, depend on these types of neglected plant resources that are grown naturally in and around the agricultural lands, wasted lands, close to water sources and forest areas. Photo by: Rajendra Kumar Basnet Kindly supported by Misereor and Bread for the World Parallel Information The Right to Adequate Food in Nepal (Article 11, ICESCR) FIAN Nepal August 2014, Kathmandu Parallel Information: The right to adequate food in Nepal, (Article 11, ICESCR) ii Abbreviations ADS : Agriculture Development Strategy AVR : Antiretroviral CBS : Central Bureau of Statistics CESCR : Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights CEDAW : Committee on Elimination of Discrimination against Women CSO : Civil Society Organisations DAO : District Administration Office DFID : Department of International Development DANIDA : Danish International Development -

Rakam Land Tenure in Nepal

47 TRENDS OF WOMEN'S CANDIDACY IN NATIONAL ELECTIONS OF NEPAL Amrit Kumar Shrestha Lecturer (Political Science) Mahendra Multiple Campus, Dharan [email protected] Abstract The study area of this article is women's candidacy in national elections of Nepal. It focuses on five national elections held from 1991 to 2013. It is based on secondary source of data. The Election Commission of Nepal publishes a report after every election. Data are extracted from the reports published by the Election Commission and analyzed with the help of the software SPSS. This article analyzes only facts regarding the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system. Such a study is important in order to lead to new affirmative action policies that will enhance gender mainstreaming and effective participation in all leadership and development processes. The findings will also be resourceful to scholars who are working in this field. The findings from this investigation provide evidence that the number of women candidates in national elections seems almost invisible in an overwhelming crowd of men candidates. The number of elected women candidates is very few. Similarly, distribution of women candidates is unequal in geographical regions. Where the human development rate is high the number of women candidates is greater. The roles of political parties of Nepal are not profoundly positive to increase women's candidacy. Likewise, electoral systems are responsible to influence women‟s chances of being elected. FPTP electoral system is not more favorable for women candidates. This article recommends that if a constituency would reserve only for women among three through FPTP then the chances of 33 percent to win the elections by women would be secured. -

Nepal's Peace Agreement: Making It Work

NEPAL’S PEACE AGREEMENT: MAKING IT WORK Asia Report N°126 – 15 December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. APRIL AFTERMATH................................................................................................... 2 A. FROM POPULAR PROTEST TO PARLIAMENTARY SUPREMACY ................................................2 B. A FUNCTIONAL GOVERNMENT?..............................................................................................3 C. CONTESTED COUNTRY ...........................................................................................................5 III. THE TALKS ................................................................................................................... 6 A. A ROCKY START...................................................................................................................6 1. Eight-point agreement.................................................................................................6 2. Engaging the UN ........................................................................................................7 3. Mutual suspicion.........................................................................................................8 B. THE STICKING POINTS............................................................................................................8 1. Arms -

Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State Protection – Local Government – Ward Chairmen

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NPL17502 Country: Nepal Date: 2 September 2005 Keywords: Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State protection – Local government – Ward Chairmen This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? 2. Do the Maoists have an office in Chitwan? Letter head paper or contact address? 3. What is a Ward and a Ward Chairman? 4. Is there evidence of the Maoists targeting members of Municipal councils or Ward Chairmen? RESPONSE 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? Activities A December 2002 Research Response provides information on Maoists in Chitwan suggesting it is a quiet area and they are mainly active in remote villages (RRT Country Research 2002 Research Response NPL17502, 24 December, question 1 – Attachment 1). A recent news item from the al Jazeera website refers to the Maoist-controlled district of Chitwan (‘Nepal blast triggers hunt for Maoists’ 2005, al Jazeera website, source: AFP, 6 June http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/9F7BE0A5-E320-4C5B-BD03- 7151D63A574F.htm - accessed 1 September 2005 - Attachment 2). -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

IBN, GMR Interaction with Locals

IBN DISPATCH Year:1, Issue:3, Chaitra 2071 (March-April 2015) Monthly Newsletter IBN, GMR Interaction with Locals KATHMANDU: Investment Board Nepal (IBN) Speaking on the occasion, Harvindar Manocha, and GMR-ITD, developer of 900MW Upper chief of GMR’s Nepal Office, reiterated the Karnali Hydropower Project (UKHPP), jointly commitment of accelerating construction organized interactions with local stakeholders in activities at the project-affected area soon. He project-affected districts from February 23-28. said the company will soon prepare a detailed The interactions, mainly aimed at sharing benefits package in collaboration with the locals, the major features of Project Development and start implementing it at the earliest. Agreement (PDA), were conducted at Dab Likewise, IBN CEO Pant said the PDA has (project’s dam-site) protected the and Dailekh Bazaar national interests. of Dailekh district, He further said the Birendranagar of project will bring Surkhet district, huge economic and and Bhairabsthan social transformations and Mangalsen of in the districts. He Achham district. also assured the A high level IBN locals that their team, led by its Chief genuine demands, Executive Officer including the issues (CEO) Radhesh of rehabilitation Pant and GMR’s and resettlement, senior officials, compensation for Constituent Assembly (CA) members of Dailekh, the land acquired and other benefits, will be Surkhet, Achham and Sankhuwasabha districts, adequately addressed by the company. In and Kathmandu-based journalists attended regards with the local benefits and rehabilitation the interactions. Local political parties, local and resettlement activities, CEO Pant said the government officials, Project Concern Groups company will follow international standards, and media representatives shared their views at including that of International Finance the events. -

Cultural Beliefs and Traditional Rituals About Child Birth Practice in Rural, Nepal

MOJ Public Health Cultural Beliefs and Traditional Rituals about Child Birth Practice in Rural, Nepal Abstract Research Article Background: Volume 5 Issue 1 - 2016 About 98% of newborn deaths occur in developing countries, where most newborns deaths occur at home [1]. In Nepal, approximately, 90% Action Works Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal of deliveries take place at home [2]. Information about reasons for delivering at home and newborn care practices in rural areas of Nepal is lacking and such *Corresponding author: Sanjaya Bahadur Chand, Health informationObjectives: will be useful for policy makers. Tel: +977 9851202315; Email: The objective of this study is to explore and analyze the cultural Project Officer, Action Works Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal, beliefsMethods: and traditional rituals about child birth practice in rural, Nepal. A cross-sectional survey was carried out in the Kesharpur primary Received: June 06, 2016 | Published: health care centre of Baitadi district, Far western Nepal during April - May, 2013. November 04, 2016 Self administered questionnaire to the reproductive age (15-49) year’s women whoResults: experienced home delivery during the last year and new pregnant. A total of 100 mothers were interviewed. 13% were deliveries at health institute and 87% were at home deliveries. Only 20% of deliveries had a skilled birth attendant present and 80% mothers gave birth from others support and alone. Only 1% women were live in hospital during postpartum period, 60% lived in home and 39% in cow shed. Only 45% had used a clean home delivery kit and only 66% were use boiled string or threat for cord tie. Maximum women were practice wood for cord cut surface 43%. -

Jumla Community Development Project a Project Proposal

Jumla Community Development Project A Project Proposal April 2011 – December 2014 by Govinda Development Aid Association, Aalen, Germany in cooperation with Shangrila Association, Jumla, Nepal Jumla Community Development Project • April 2011 – December 2014 2 Table of contents 1. Background..........................................................................................6 2. Problems, opportunities and development intervention..................7 3. Project Beneficiaries.........................................................................12 4. Project Description............................................................................12 4.1 Project goal .....................................................................................13 4.2 Project purposes/ outcomes..........................................................13 4.3 Project Outputs ...............................................................................14 4.4 Project Activities.............................................................................15 5. Project Methodology .........................................................................24 5.1 Self-help groups and Cooperative organization ..........................25 5.2 Horizontal learning .........................................................................25 5.3 Affirmative action............................................................................25 5.4 Use of different methods in awareness and educative process 25 5.5 Team building and office set up ....................................................26 -

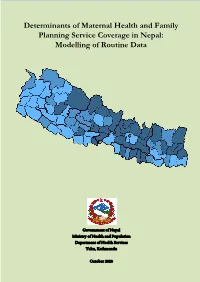

Determinants of Maternal Health and Family Planning Service Coverage in Nepal: Modelling of Routine Data

Determinants of Maternal Health and Family Planning Service Coverage in Nepal: Modelling of Routine Data Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population Department of Health Services Teku, Kathmandu October 2020 Disclaimer: This analysis was carried out under the aegis of Integrated Health Information Management Section (IHIMS), Management Division, Department of Health Services (DoHS), Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP). This analysis is made possible with the UKaid through the Nepal Health Sector Programme 3 (NHSP3), Monitoring, Evaluation and Operational Research (MEOR) project and by the generous support of the American people through United States Agency for International Development (USAID)’s Strengthening Systems for Better Health (SSBH) Activity. The content of this report is produced by IHIMS, Abt Associates Inc., SSBH program and NHSP3, MEOR project. The views expressed in the report are of those who contributed to carry out and complete the analysis and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government and British Embassy Kathmandu or the UK Government. Additional information about the analysis may be obtained from the IHIMS, Management Division, DoHS, MoHP, Teku Kathmandu; Telephone: +977-1-4257765; internet: http://www.mddohs.gov.np; or UKaid/NHSP3/MEOR project, email: [email protected]. Recommended Citation Department of Health Services (DoHS), Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), Nepal; UKaid Nepal Health Sector Programme 3 (NSHP3)/Monitoring, Evaluation and Operational Research