SHIOHARA, Asako, 2013. 'Voice in the Sumbawa Besar Dialect Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report Volume V Supporting Report 3

No. JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY MINISTRY OF SETTLEMENT & REGIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA THE STUDY ON RURAL WATER SUPPLY PROJECT IN NUSA TENGGARA BARAT AND NUSA TENGGARA TIMUR FINAL REPORT VOLUME V SUPPORTING REPORT 3 CONSTRUCTION PLAN AND COST ESTIMATES Appendix 11 CONSTRUCTION PLAN Appendix 12 COST ESTIMATES MAY 2002 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. NIHON SUIDO CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. SSS J R 02-102 Exchange Rate as of the end of October 2001 US$1 = JP¥121.92 = Rp.10,435 LIST OF VOLUMES VOLUME I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VOLUME II MAIN REPORT VOLUME III SUPPORTING REPORT 1 WATER SOURCES Appendix 1 VILLAGE MAPS Appendix 2 HYDROMETEOROLOGICAL DATA Appendix 3 LIST OF EXISTING WELLS AND SPRINGS Appendix 4 ELECTRIC SOUNDING SURVEY / VES-CURVES Appendix 5 WATER QUALITY SURVEY / RESULTS OF WATER QUALITY ANALYSIS Appendix 6 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS AND ANALYSIS METHODS Appendix 7 TEST WELL DRILLING AND PUMPING TESTS VOLUME IV SUPPORTING REPORT 2 WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM Appendix 8 QUESTIONNAIRES ON EXISTING WATER SUPPLY SYSTEMS Appendix 9 SURVEY OF EXISTING VILLAGE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEMS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Appendix 10 PRELIMINARY BASIC DESIGN STUDIES VOLUME V SUPPORTING REPORT 3 CONSTRUCTION PLAN AND COST ESTIMATES Appendix 11 CONSTRUCTION PLAN Appendix 12 COST ESTIMATES VOLUME VI SUPPORTING REPORT 4 ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT Appendix 13 SOCIAL DATA Appendix 14 SUMMARY OF VILLAGE PROFILES Appendix 15 RAPID RURAL APPRAISAL / SUMMARY SHEETS OF RAPID RURAL APPRAISAL (RRA) SURVEY Appendix 16 SKETCHES OF VILLAGES Appendix 17 IMPLEMENTATION PROGRAM -

Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: Effects of Altitude, the 1815 Cataclysmic Volcanic Eruption and Trade

FORKTAIL 18 (2002): 49–61 Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade COLIN R. TRAINOR In June-July 2000, a 10-day avifaunal survey on Gunung Tambora (2,850 m, site of the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history), revealed an extraordinary mountain with a rather ordinary Sumbawan avifauna: low in total species number, with all species except two oriental montane specialists (Sunda Bush Warbler Cettia vulcania and Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophrys) occurring widely elsewhere on Sumbawa. Only 11 of 19 restricted-range bird species known for Sumbawa were recorded, with several exceptional absences speculated to result from the eruption. These included: Flores Green Pigeon Treron floris, Russet-capped Tesia Tesia everetti, Bare-throated Whistler Pachycephala nudigula, Flame-breasted Sunbird Nectarinia solaris, Yellow-browed White- eye Lophozosterops superciliaris and Scaly-crowned Honeyeater Lichmera lombokia. All 11 resticted- range species occurred at 1,200-1,600 m, and ten were found above 1,600 m, highlighting the conservation significance of hill and montane habitat. Populations of the Yellow-crested Cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea, Hill Myna Gracula religiosa, Chestnut-backed Thrush Zoothera dohertyi and Chestnut-capped Thrush Zoothera interpres have been greatly reduced by bird trade and hunting in the Tambora Important Bird Area, as has occurred through much of Nusa Tenggara. ‘in its fury, the eruption spared, of the inhabitants, not a although in other places some vegetation had re- single person, of the fauna, not a worm, of the flora, not a established (Vetter 1820 quoted in de Jong Boers 1995). blade of grass’ Francis (1831) in de Jong Boers (1995), Nine years after the eruption the former kingdoms of referring to the 1815 Tambora eruption. -

Zoologische Verhandelingen

CRUSTACEA LIBRARY SMITHSONIAN INST. RETURN TO W-119 ZOOLOGISCHE VERHANDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) No. 162 A COLLECTION OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEA FROM SUMBA, LESSER SUNDA ISLANDS, INDONESIA by L. B. HOLTHUIS LEIDEN E. J. BRILL 14 September 1978 ZOOLOGISCHE VERHANDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJIC WERK) No. 162 A COLLECTION OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEA FROM SUMBA, LESSER SUNDA ISLANDS, INDONESIA by i L. B. HOLTHUIS LEIDEN E. J. BRILL 14 September 1978 Copyright 1978 by Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this hook may he reproduced or translated in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS A COLLECTION OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEA FROM SUMBA, LESSER SUNDA ISLANDS, INDONESIA by L. B. HOLTHUIS Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historic, Leiden, Netherlands With 14 text-figures and 1 plate The Sumba-Expedition undertaken by Dr. E. Sutter of the Naturhistori- sches Museum of Basle and Dr. A. Biihler of the Museum fur Volkerkunde of the same town, visited the Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia, in 1949. Dr. Sutter, the zoologist, stayed in the islands from 19 May to 26 November; most of the time was spent by him in Sumba (21 May-31 October), and extensive collections were made there, among which a most interesting material of Decapod Crustacea, which forms the subject of the present paper. A few Crustacea were collected on the islands of Sumbawa (on 19 May) and Flores (19 and 21 November). -

A Stigmatised Dialect

A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT Zulfadli Bachelor of Education (Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia) Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) Thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide December 2014 ii iii iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT i TABLE OF CONTENTS v LIST OF FIGURES xi LIST OF TABLES xv ABSTRACT xvii DECLARATION xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xxi CHAPTER 1 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Preliminary Remarks ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Acehnese society: Socioeconomic and cultural considerations .......................... 1 1.2.1 Acehnese society .................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 Population and socioeconomic life in Aceh ......................................... 6 1.2.3 Workforce and population in Aceh ...................................................... 7 1.2.4 Social stratification in Aceh ............................................................... 13 1.3 History of Aceh settlement ................................................................................ 16 1.4 Outside linguistic influences on the Acehnese ................................................. 19 1.4.1 The Arabic language.......................................................................... -

Henri Chambert-Loir

S t a t e , C it y , C o m m e r c e : T h e C a s e o f B im a ' Henri Chambert-Loir On the map of the Lesser Sunda Islands, between Bali and Lombok in the west and Flores, Sumba, and Timor in the east, lies the island of Sumbawa, a compact, homogenous fief of Islam in the midst of a religious mosaic, of which history has not yet finished modi fying the pattern. From west to east the island, which forms part of the Nusa Tenggara province, is divided into three kabupaten : Sumbawa, Dompu, and Bima. Today the latter contains almost 430,000 inhabitants,* 1 of whom probably 70,000 live in the twin agglomera tions of Bima and Raba. The Present Town The Raba quarter developed at the beginning of this century when the kingdom of Bima was integrated into the Netherlands Indies. It contains the main administrative buildings: the offices of the bupati, located in the foimer house of the Assistant-Resident, the regional parliament (DPRD), and the local headquarters of the various administrative services. The urban center remains that of the former capital o f the sultanate, in the vicinity of the bay. In contrast to the governmental pole concentrated in Raba, the agglomeration of Bima contains the main centers of social life, both past and present. The former palace of the Sultans (N° 4 on Fig. 2) is an imposing masonry edifice built at the beginning of this century. Today it is practically deserted and will probably be converted into a museum. -

Pulau Bali Dan Kepulauan Nusa Tenggara

SINKRONISASI PROGRAM DAN PEMBIAYAAN PEMBANGUNAN JANGKA PENDEK 2018 - 2020 KETERPADUAN PENGEMBANGAN KAWASAN DENGAN INFRASTRUKTUR PEKERJAAN UMUM DAN PERUMAHAN RAKYAT PULAU BALI DAN KEPULAUAN NUSA TENGGARA PUSAT PEMROGRAMAN DAN EVALUASI KETERPADUAN INFRASTRUKTUR PUPR BADAN PENGEMBANGAN INFRASTRUKTUR WILAYAH KEMENTERIAN PEKERJAAN UMUM DAN PERUMAHAN RAKYAT JUDUL: Sinkronisasi Program dan Pembiayaan Pembangunan Jangka Pendek 2018-2020 Keterpaduan Pengembangan Kawasan dengan Infrastruktur PUPR Pulau Bali dan Kepulauan Nusa Tenggara PEMBINA: Kepala Badan Pengembangan Infrastruktur Wilayah: Ir. Rido Matari Ichwan, MCP. PENANGGUNG JAWAB: Kepala Pusat Pemrograman dan Evaluasi Keterpaduan Infrastruktur PUPR: Ir. Harris H. Batubara, M.Eng.Sc. PENGARAH: Kepala Bidang Penyusunan Program: Sosilawati, ST., MT. TIM EDITOR: 1. Kepala Sub Bidang Penyusunan Program I: Amelia Handayani, ST., MSc. 2. Kepala Sub Bidang Penyusunan Program II: Dr.(Eng.) Mangapul L. Nababan, ST., MSi. PENULIS: 1. Kepala Bidang Penyusunan Program: Sosilawati, ST., MT. 2. Kepala Sub Bidang Penyusunan Program II: Dr.(Eng.) Mangapul L. Nababan, ST., MSi. 3. Pejabat Fungsional Perencana: Ary Rahman Wahyudi, ST., MUrb&RegPlg. 4. Pejabat Fungsional Perencana: Zhein Adhi Mahendra , SE. 5. Staf Bidang Penyusunan Program: Wibowo Massudi, ST. 6. Staf Bidang Penyusunan Program: Oktaviani Dewi, ST. KONTRIBUTOR DATA: 1. Nina Mulyani, ST. 2. Oktaviani Dewi, ST. 3. Ervan Sjukri, ST. DESAIN SAMPUL DAN TATA LETAK: 1. Wantarista Ade Wardhana, ST. 2. Wibowo Massudi, ST. TAHUN : 2017 ISBN : ISBN 978-602-61190-0-1 PENERBIT : PUSAT PEMROGRAMAN DAN EVALUASI KETERPADUAN INFRASTRUKTUR PUPR, BADAN PENGEMBANGAN INFRASTRUKTUR WILAYAH, KEMENTERIAN PEKERJAAN UMUM DAN PERUMAHAN RAKYAT. i KATA PENGANTAR Kepala Pusat Pemrograman dan Evaluasi Keterpaduan Infrastruktur PUPR Assalamu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh; Salam Sejahtera; Om Swastiastu; Namo Buddhaya. -

'Tense, Aspect, Mood and Polarity in the Sumbawa Besar Dialect Of

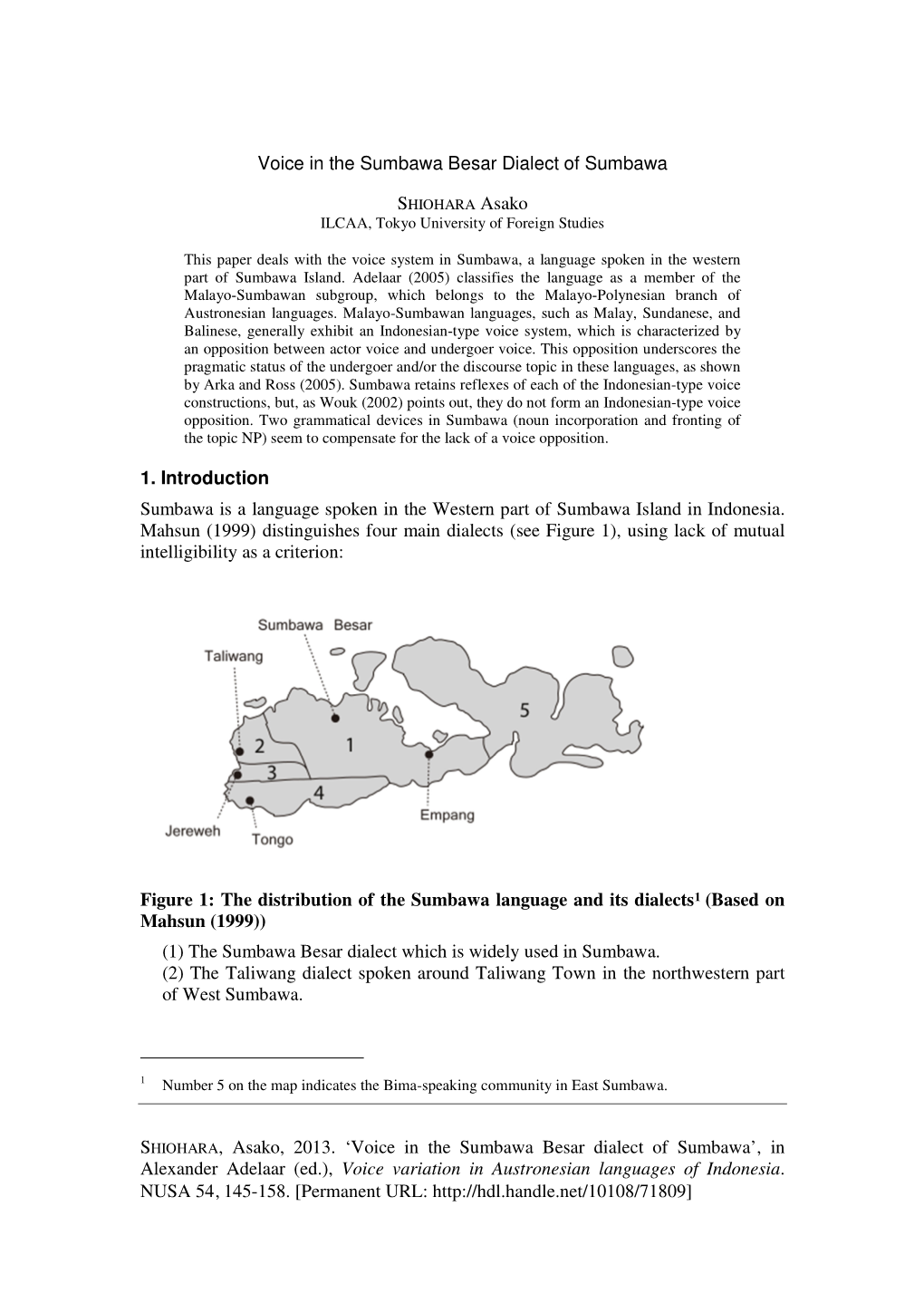

Tense, Aspect, Mood and Polarity in the Sumbawa Besar Dialect of Sumbawa SHIOHARA Asako ILCAA, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Sumbawa is a language spoken in the western part of Sumbawa Island in Indonesia. Sumbawa exhibits three tense distinctions (past /present /future), which is unusual among languages in the Malayo-Sumbawan subgroup. It also has devices to mark inchoative aspect and several modal meanings. These tense, aspectual and modal distinctions are mainly achieved by two morpho-syntactic categories, namely the tense-modal (TM) marker and the aspect-modal (AM) clitic, which are considered to be independently occurring developments; no PAn verbal morphology is retained in this language. The negator nó appears in eight combinations with the tense marker ka ‘past’ and/or the aspect-modal clitics. This, too, is considered to be a local development. 1. Introduction1 Sumbawa is a language spoken in the western part of Sumbawa Island in Indonesia. According to Adelaar (2005), Sumbawa belongs to the Malayo-Sumbawan subgroup, which is a (western) member of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. Within the Sumbawa language, Mahsun (1999) distinguishes four main dialects on the basis of basic vocabulary. The Sumbawa dialects are illustrated in map one. Map 1: Distribution of Sumbawa language and dialects2 (Based on Mahsun (1999)) 1 This study is based on conversational data gathered in Sumbawa Besar and Empang, Sumbawa, NTB between 1996 and 2013. I am very grateful to the Sumbawa speakers who assisted me by sharing their knowledge of their language, especially Dedy Muliyadi (Edot), Papin Agang Patawari (Dea Papin Dea Ringgi), and the late Pin Awak (Siti Hawa). -

Sasak Granary Is As a Clinic of Controlling of Language Used the Tourism Areas in Lombok

Sasak Granary is as a Clinic of Controlling of Language Used the Tourism Areas in Lombok Muh. Jaelani Al-Pansoria, Herman Wijayaa, Roni Amrulloh, M.Hum a a Study Program of Indonesian Language and Literature Education , Hamzanwadi University Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract: Tourism area is an area that has susceptibility in change, interference, and extinct of language and culture. This theoretical study aims to recommend “Lumbung Sasak” language and culture clinic as model to publish language usage in Lombok tourism area. The development of Lumbung Sasak function as language and tourism clinic will bring positive effect in preservation, development, existence of language and culture. Besides tourists will know some languages and cultures by joining sort course and see other works and culture in Lumbung Sasak. Keywords: Lumbung Sasak, bilingual, language and tourim Social interaction that occurs in society does not escape the important role of a person in mastering language. Language as an object of research is never used up to be investigated because in language research, the point of view can create the object of research (Kridalaksana, 2002). That is what makes linguistic research diverse and widespread. It's just that linguistic research in Southeast Asia more focuses on studies about sociolinguistics and psycholinguistics. Zen research results (2017) about "Mapping of bilingual research in 2003- 2016" Research on linguistics in Southeast Asia over the years, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, tends to focus on Sociolinguistic and Psycholinguistic studies. Research on Bilingual in the aspects of language policy and trilingual acquisitions has not been done so much. -

International Seminar “Language Maintenance and Shift” July 2, 2011

International Seminar “Language Maintenance and Shift” July 2, 2011 I International Seminar “Language Maintenance and Shift” July 2, 2011 CONTENTS Editors‟ Note PRESCRIPTIVE VERSUS DESCRIPTIVE LINGUISTICS FOR LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE: WHICH INDONESIAN SHOULD NON-NATIVE SPEAKERS LEARN? 1 - 7 Peter Suwarno PEMBINAAN DAN PENGEMBANGAN BAHASA DAERAH? 8 - 11 Agus Dharma REDISCOVER AND REVITALIZE LANGUAGE DIVERSITY 12 - 21 Stephanus Djawanai IF JAVANESE IS ENDANGERED, HOW SHOULD WE MAINTAIN IT? 22 - 30 Herudjati Purwoko LANGUAGE VITALITY: A CASE ON SUNDANESE LANGUAGE AS A SURVIVING INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE 31 - 35 Lia Maulia Indrayani MAINTAINING VERNACULARS TO PROMOTE PEACE AND TOLERANCE IN MULTILINGUAL COMMUNITY IN INDONESIA 36 - 40 Katharina Rustipa FAMILY VALUES ON THE MAINTENANCE OF LOCAL/HOME LANGUAGE 41 - 45 Layli Hamida LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AND STABLE BILINGUALISM AMONG SASAK- SUMBAWAN ETHNIC GROUP IN LOMBOK 46 - 50 Sudirman Wilian NO WORRIES ABOUT JAVANESE: A STUDY OF PREVELANCE IN THE USE OF JAVANESE IN TRADITIONAL MARKETS 51 - 54 Sugeng Purwanto KEARIFAN LOKAL SEBAGAI BAHAN AJAR BAHASA INDONESIA BAGI PENUTUR ASING 55 - 59 Susi Yuliawati dan Eva Tuckyta Sari Sujatna MANDARIN AS OVERSEAS CHINESE‟S INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE 60 - 64 Swany Chiakrawati BAHASA DAERAH DALAM PERSPEKTIF KEBUDAYAAN DAN SOSIOLINGUISTIK: PERAN DAN PENGARUHNYA DALAM PERGESERAN DAN PEMERTAHANAN BAHASA 65 - 69 Aan Setyawan MENILIK NASIB BAHASA MELAYU PONTIANAK 70 - 74 Evi Novianti II International Seminar “Language Maintenance and Shift” July 2, 2011 PERGESERAN DAN PEMERTAHANAN -

Cover Page BOSS

Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Promoting Rural Income through Support for Markets in Agriculture (AIP-PRISMA) BEEF GROWTH STRATEGY DOCUMENT FOR NUSA TENGGARA BARAT PROVINCE October 2015 1 Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Promoting Rural Income through Support for Markets in Agriculture (AIP-PRISMA) Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 4 2. Background 5 3. Sector Description 5 3.1 Sector profile 5 3.1.1 Overall context 5 3.1.2 Local context 7 3.2 Sector dynamics 8 3.2.1 Market overview 8 3.2.2 Sector map 9 3.2.3 Core value chain 9 Inputs 9 Production 11 Cattle marketing 12 3.2.4 Supporting functions and services 13 4. Analysis 16 4.1 Problems in core functions and their underlying causes 16 4.1.1 Problems faced by farmers and their underlying causes 16 4.1.2 Problems, underlying causes and their impact on farmers faced by other actors 17 4.2 Weaknesses in services, rules and regulations 18 4.3 Cross-cutting issues (gender and environment) 19 5. Strategy for Change 19 5.1 Market potential 19 5.2 Vision of change 20 5.3 Interventions 20 5.4 Sequencing and prioritisation of interventions 21 5.5 Sector vision of change logic 21 Annex 1: Intervention Logic Analysis Framework (ILAF) Annex 2: Identified market actors Annex 3: List of Respondents Annex 6: Investigation team Tables & Figures Figure 1: Global international production and consumption of beef, 2003-2013 ........................ 5 Figure 2: Cattle population by province 2012-2013 ................................................................... 7 Figure 3: Main livestock growing poverty prone districts in NTB .............................................. -

Sosial Humaniora TAMBORA SEBUAH PERJALANAN VISUAL

JURNAL TAMBORA VOL. 4 NO. 1 FEBRUARI 2020 http://jurnal.uts.ac.id Sosial Humaniora TAMBORA SEBUAH PERJALANAN VISUAL Aka Kurnia S F1*, M Syukron Anshori2 1*Fakultas Ilmu Komunikasi Universitas Teknologi Sumbawa 2Fakultas Ilmu Komunikasi Universitas Teknologi Sumbawa *Corresponding Author email: [email protected] Abstrak Diterima Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk merefleksikan kembali 200 tahun letusan Bulan Januari gunung Tambora yang berada di pulau Sumbawa Nusa Tenggara Barat melalui 2020 perjalanan dengan pendekatankajian fotografi,khususnyatravel photography. Sejak awal kehadirannyafotografi telah memainkan peran secara konstitutif dalam membentuk sebuah catatan perjalanan, hal ini juga sebanding dengan Diterbitkan pentingnya peran tersebut sebagai penggambaran identitas sosial (Osborne, Bulan Februari 2000). Selain itu, travel photography juga menjadi cara untuk melihat 2020 pengalaman melalui otentikasi visual (Hilman Wendy, 2007).Gunung Tambora meletus pada April 1815, berdampak pada perubahan iklim dunia dan bencana alam yang memakan korban 84.000 jiwa di pulau Sumbawa, serta mengubur Keyword : kerajaan Tambora dan Pekat.. Berdasarkan hasil penelitian, peneliti melihat Komunikasi, terjadinya rekonstruksi pemaknaan dalam sejarah letusan gunung Tambora yang Travel tidak hanya dilihat sebagai sebuah gunung, namun juga sebagai sebuah identitas Photography, dalam struktur sosial kemasyarakatan dalam bentuk karya fotografi. Seorang Tambora, 1815, fotografer berperandalam menciptakan sebuah realitas sejak pre-travel hingga Sumbawa, post-travel. Climate Change, Semiotika PENDAHULUAN Dampak Letusan Letusan Tambora berdampak pada skala Gunung Tambora meletus pada April 1815, lokal, nasional dan internasional yang berlangsung berdampak pada perubahan iklim dunia dan bencana dari tanggal 5-17 April yang mengubur dua kerajaan alam yang memakan korban 84.000 jiwa di pulau di sekitar Gunung Tambora, yakni kerajaan Sumbawa. -

Case of Great Tambora Eruption 1815

Interpretation of Past Kingdom’s Poems to Reconstruct the Physical Phenomena in the Past: Case of Great Tambora Eruption 1815 Mikrajuddin Abdullah Department of Physics, Bandung Institute of Technology, Jl. Ganesa 10 Bandung 40132, Indonesia and Bandung Innovation Center Jl. Sembrani No 19 Bandung, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract In this paper I reconstruct the distribution of ash released from great Tambora eruption in 1815. The reconstruction was developed by analyzing the meaning of Poem of Bima Kingdom written in 1830. I also compared the effect of Tambora eruption and the Kelud eruption February 13, 2014 to estimate the most logical thickness of ash that has fallen in Bima district. I get a more logical value for ash thickness in Bima district of around 60 cm, not 10 cm as widely reported. I 1 also propose the change of ahs distribution. Until presently, it was accaepted that the ash thickness distributiom satisfied asymmetry cone distribution. However, I propose the ash distributed according to asymmetry Gaussian function. Random simulation and fitting of the thickness data extracted from isopach map showed that the asymmetry Gaussian distribution is more acceptable. I obtained the total volume of ash released in Tambora eruption was around 180 km3, greater of about 20% than the present accepted value of 150 km3. Keywords: Tambora eruption, poem of Bima Kingdom, isopach, ash distribution, asymmetry Gaussian, random simulation. I. INTRODUCTION What the scientists do to explain phenomena in the past during which science was unde developed? What the scientists do to reconstruct phenomena in the past at locations where scientific activities were under established? A most common approach is by excavating the location at which the events have happened and analyzing the collected results using modern science methods.