Nureyev, Rudolf (1938-1993) by Douglas Blair Turnbaugh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Final January 2019 Newsletter 1-2-19

January 2019 Talking Pointes Jane Sheridan, Editor 508.367.4949 [email protected] From the Desk of the President Showcase Luncheon Richard March 941.343.7117 “Our Dancers—The Boys From [email protected] Brazil” Monday, February 11, 2019, Bird I’m excited for you to read about our winter party – Key Yacht Club, 11:30 AM Carnival at Mardi Gras – elsewhere in this newsletter. It will be at the Hyatt Boathouse on Carnival at Mardi Gras February 25th. This is a chance to have fun with other Monday, February 25, 2019, The Boathouse at the Hyatt Regency, Friends and dancers from the Company. It is also an 5:30 PM - 7:30 PM opportunity to help us raise funds for the Ballet. We need help in preparing a number of themed “Spring Fling” baskets that will be auctioned at the event. In the past, Sunday, March 31, 2019, The we’ve had French, Italian, wine, and chocolate Sarasota Garden Club, 4:00 PM – baskets, among others. Those who prepare baskets are 6:30 PM asked to spend no more than $50 in preparing them. However, you can add an unlimited number of gift Showcase Luncheon certificates or donations that will increase the appeal. Margaret Barbieri, Assistant Director, The Sarasota Ballet, If you would like to pitch in to support this effort, "Giselle: Setting An Iconic Work” please contact Phyllis Myers for information at Monday, April 15, 2019, Michael’s [email protected]. And, please come to On East, 11:30 AM the party. I am certain you will have fun! Were you able to see the performance of our dancers Pointe of Fact from the Studio Company and the Margaret Barbieri November was a record-setting Conservatory at the Opera House? Together with the month for the Friends of The Key Chorale, they took part in a program called Sarasota Ballet. -

World Premiere of Angels' Atlas by Crystal Pite

World Premiere of Angels’ Atlas by Crystal Pite Presented with Chroma & Marguerite and Armand Principal Dancer Greta Hodgkinson’s Farewell Performances Casting Announced February 26, 2020… Karen Kain, Artistic Director of The National Ballet of Canada, today announced the casting for Angels’ Atlas by Crystal Pite which makes its world premiere on a programme with Chroma by Wayne McGregor and Marguerite and Armand by Frederick Ashton. The programme is onstage February 29 – March 7, 2020 at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts. #AngelsAtlasNBC #ChromaNBC #MargueriteandArmandNBC The opening night cast of Angels’ Atlas features Principal Dancers Heather Ogden and Harrison James, First Soloist Jordana Daumec, Hannah Fischer and Donald Thom, Second Soloists Spencer Hack and Siphesihle November and Corps de Ballet member Hannah Galway. Principal Dancer Greta Hodgkinson retires from the stage after a career that has spanned over a period of 30 years. She will dance the role of Marguerite opposite Principal Dancer Guillaume Côté in Marguerite and Armand on opening night. The company will honour Ms. Hodgkinson at her final performance on Saturday, March 7 at 7:30 pm. Principal Dancers Sonia Rodriguez, Francesco Gabriele Frola and Harrison James will dance the title roles in subsequent performances. Chroma will feature an ensemble cast including Principal Dancers Skylar Campbell, Svetlana Lunkina, Heather Ogden and Brendan Saye, First Soloists Tina Pereira and Tanya Howard, Second Soloists Christopher Gerty, Siphesihle November and Brent -

An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria

Friday 24 April Sadler’s Wells Digital Stage An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria Natalia Osipova is a major star in the dance world. She started formal ballet training at age 8, joining the Bolshoi Ballet at age 18 and dancing many of the art form’s biggest roles. After leaving the Bolshoi in 2011, she joined American Ballet Theatre as a guest dancer and later the Mikhailovsky Ballet. She joined The Royal Ballet as a principal in 2013 after her guest appearance in Swan Lake. This showcase comprises of three of Natalia’s most captivating appearances on the Sadler’s Wells stage. Featuring Valse Triste, specially created for Natalia and American Ballet Theatre principal David Hallberg by Alexei Ratmansky, and the beautifully emotive Ave Maria by Japanese choreographer Yuka Oishi set to the music of Schubert, both of which premiered in 2018 at Sadler’s Wells’ as part of Pure Dance. The programme will also feature Qutb, a uniquely complex and intimate work by Sadler’s Wells Associate Artist Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, which premiered in 2016 as part of Natalia’s first commission alongside works by Arthur Pita and fellow Associate Artist Russell Maliphant. VALSE TRISTE, PURE DANCE 2018 Natalia Osipova Russian dancer Natalia Osipova is a Principal of The Royal Ballet. She joined the Company as a Principal in autumn 2013, after appearing as a Guest Artist the previous Season as Odette/Odile (Swan Lake) with Carlos Acosta. Her roles with the Company include Giselle, Kitri (Don Quixote), Sugar Plum Fairy (The Nutcracker), Princess Aurora (The Sleeping Beauty), Lise (La Fille mal gardée), Titania (The Dream), Marguerite (Marguerite and Armand), Juliet, Tatiana (Onegin), Manon, Sylvia, Mary Vetsera (Mayerling), Natalia Petrovna (A Month in the Country), Anastasia, Gamzatti and Nikiya (La Bayadère) and roles in Rhapsody, Serenade, Raymonda Act III, DGV: Danse à grande vitesse and Tchaikovsky Pas de deux. -

Premieres on the Cover People

PDL_REGISTRATION_210x297_2017_Mise en page 1 01.06.17 10:52 Page1 Premieres 18 Bertaud, Valastro, Bouché, BE PART OF Paul FRANÇOIS FARGUE weighs up four new THIS UNIQUE ballets by four Paris Opera dancers EXPERIENCE! 22 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas MIKE DIXON considers Daniel de Andrade's take on John Boyne's wartime novel 34 Swan Lake DEBORAH WEISS on Krzysztof Pastor's new production that marries a slice of history with Reece Clarke. Photo: Emma Kauldhar the traditional story P RIX 38 Ballet of Difference On the Cover ALISON KENT appraises Richard Siegal's new 56 venture and catches other highlights at Dance INTERNATIONAL BALLET COMPETITION 2017 in Munich 10 Ashton JAN. 28 TH – FEB. 4TH, 2018 AMANDA JENNINGS reviews The Royal DE Ballet's last programme in London this Whipped Cream 42 season AMANDA JENNINGS savours the New York premiere of ABT's sweet confection People L A U S ANNE 58 Dangerous Liaisons ROBERT PENMAN reviews Cathy Marston's 16 Zenaida's Farewell new ballet in Copenhagen MIKE DIXON catches the live relay from the Royal Opera House 66 Odessa/The Decalogue TRINA MANNINO considers world premieres 28 Reece Clarke by Alexei Ratmansky and Justin Peck EMMA KAULDHAR meets up with The Royal Ballet’s Scottish first artist dancing 70 Preljocaj & Pite principal roles MIKE DIXON appraises Scottish Ballet's bill at Sadler's Wells 49 Bethany Kingsley-Garner GERARD DAVIS catches up with the Consort and Dream in Oakland 84 Scottish Ballet principal dancer CARLA ESCODA catches a world premiere and Graham Lustig’s take on the Bard’s play 69 Obituary Sergei Vikharev remembered 6 ENTRE NOUS Passing on the Flame: 83 AUDITIONS AND JOBS 78 Luca Masala 101 WHAT’S ON AMANDA JENNINGS meets the REGISTRATION DEADLINE contents 106 PEOPLE PAGE director of Academie de Danse Princesse Grace in Monaco Front cover: The Royal Ballet - Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle in Ashton's Marguerite and Armand. -

Ashton Triple Cast Sheet 16 17 ENG.Indd

THE ROYAL BALLET Approximate timings DIRECTOR KEVIN O’HARE Live cinema relay begins at 7.15pm, ballet begins at 7.30pm FOUNDER DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE FOUNDER CHOREOGRAPHER The Dream 55 minutes SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Interval FOUNDER MUSIC DIRECTOR CONSTANT LAMBERT Symphonic Variations 20 minutes PRIMA BALLERINA ASSOLUTA Interval DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE Marguerite and Armand 35 minutes The live relay will end at approximately 10.25pm Tweet your thoughts about tonight’s performance before it starts, THE DREAM during the intervals or afterwards with #ROHashton FREE DIGITAL PROGRAMME SYMPHONIC Royal Opera House Digital Programmes bring together a range of specially selected films, articles, pictures and features to bring you closer to the production. Use promo code ‘FREEDREAM’ to claim yours (RRP £2.99). VARIATIONS roh.org.uk/publications 2016/17 LIVE CINEMA SEASON MARGUERITE OTELLO WEDNESDAY 28 JUNE 2017 AND ARMAND 2017/18 LIVE CINEMA SEASON THE MAGIC FLUTE WEDNESDAY 20 SEPTEMBER 2017 LA BOHÈME TUESDAY 3 OCTOBER 2017 CHOREOGRAPHY FREDERICK ASHTON ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MONDAY 23 OCTOBER 2017 THE NUTCRACKER TUESDAY 5 DECEMBER 2017 CONDUCTOR EMMANUEL PLASSON RIGOLETTO TUESDAY 16 JANUARY 2018 TOSCA WEDNESDAY 7 FEBRUARY 2018 ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE THE WINTER’S TALE WEDNESDAY 28 FEBRUARY 2018 CONCERT MASTER VASKO VASSILEV CARMEN TUESDAY 6 MARCH 2018 NEW MCGREGOR, THE AGE OF ANXIETY, DIRECTED FOR THE SCREEN BY NEW WHEELDON TUESDAY 27 MARCH 2018 ROSS MACGIBBON MACBETH WEDNESDAY 4 APRIL 2018 MANON THURSDAY 3 MAY 2018 LIVE FROM THE SWAN LAKE TUESDAY 12 JUNE 2018 ROYAL OPERA HOUSE WEDNESDAY 7 JUNE 2017, 7.15PM For more information about the Royal Opera House and to explore our work further, visit roh.org.uk/cinema THE DREAM SYMPHONIC VARIATIONS Oberon, King of the Fairies, has quarrelled with his Queen, Titania, who refuses to MUSIC CÉSAR FRANCK hand over the changeling boy. -

ROH Weekly Announcement 27.01.21 V1

27 January 2021 #OurHouseToYourHouse The Royal Opera House announces two new Friday Premieres: Puccini’s Il trittico and Nureyev’s Raymonda Act III The Royal Opera House is delighted to continue its #OurHouseToYourHouse programme, featuring a suite of online broadcasts that can be accessed by audiences around the world for just £3. Join us next Friday 5 February at 7pm GMT as we stream Puccini’s Il trittico, comprising three one- act works. The first of these, the dark and brooding Il tabarro, is set aboard a barge on the Seine and stars Lucio Gallo as Michele, Eva-Maria Westbroek as Giorgetta and Aleksandrs Antonenko as Luigi. This is followed by Suor Angelica, with Ermonela Jaho in the title role of the nun whose familial loss and sacrifice is at the heart of this opera about religious redemption. The final work, Gianni Schicchi, centres around a family dispute over a missing will, with Lucio Gallo as Gianni Schicchi, Francesco Demuro as Rinuccio and Ekaterina Siurina as Lauretta. In this recording from 2011, the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House and the Royal Opera Chorus are conducted by Antonio Pappano. We look forward to streaming Rudolf Nureyev’s magnificent staging of Raymonda Act III by Marius Petipa on Friday 12 February at 7pm GMT. The final act of this grand ballet classic celebrates the wedding of Raymonda and the knight Jean de Brienne, featuring a range of folkdances, ensemble sequences and spectacular solos, with music by Alexander Glazunov. In this recording from 2019, the role of Raymonda is danced by Natalia Osipova, with Vadim Muntagirov as Jean de Brienne. -

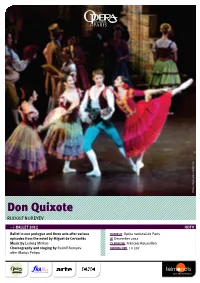

Don Quixote RUDOLF NUREYEV

s i r a P e d l a n o i t a n a r é p O : o t o h P © Don Quixote RUDOLF NUREYEV > BALLET 2012 HDTV Ballet in one prologue and three acts after various FILMED AT Opéra national de Paris episodes from the novel by Miguel de Cervantès IN December 2012 Music by Ludwig Minkus TV DIRECTOR François Roussillon Choreography and staging by Rudolf Nureyev RUNNING TIME 1 x 120’ after Marius Petipa Don Quixote artistic information DESCRIPTION “The Knight of the Sad Face” and his faithful squire, Sancho Panza, are mixed up in the wild love affairs of the stunning Kitri and the seductive Basilio in a richly colourful, humorous and virtuoso ballet. Marius Petipa’s Don Quixote premiered in Moscow in 1869 with music by Ludwig Minkus and met with resounding success from the start. The novelty lay within its break from the supernatural universe of romantic ballet. Written as if it were a play for the theatre, the work had realistic heroes and a solidly structured plot and scenes. The libretto and the choreography were handed down without interruption in Russia, but Petipa’s version remained unknown in the west for a long time. In 1981, Rudolf Nureyev introduced his own version of the work into the Paris Opera’s repertoire. While retaining the great classical pages and the strong, fiery dances, the choreographer gave greater emphasis to the comic dimension contriving a particularly lively and light-hearted production. In 2002, Alexander Beliaev and Elena Rivkina were invited to create new sets and costumes specially for the Opera Bastille. -

Dame Margot Fonteyn

www.FAMOUS PEOPLE LESSONS.com DAME MARGOT FONTEYN http://www.famouspeoplelessons.com/m/margot_fonteyn.html CONTENTS: The Reading / Tapescript 2 Synonym Match and Phrase Match 3 Listening Gap Fill 4 Choose the Correct Word 5 Spelling 6 Put the Text Back Together 7 Scrambled Sentences 8 Discussion 9 Student Survey 10 Writing 11 Homework 12 Answers 13 DAME MARGOT FONTEYN THE READING / TAPESCRIPT Margot Fonteyn was born as Margaret Hookham in England in 1919. Many consider her to be the greatest English ballerina of all time. She received the title of Dame when she was 35 from Britain’s Queen. Fonteyn had a sparkling career and encouraged artists of all kinds to share their ideas to find deeper meaning in their work. The young Margaret signed up for ballet classes when she was very young. She joined Britain’s Royal Ballet while still a teenager. Her exceptional talent was clear to see and by 1939, she was the star of her ballet company. She wowed TV audiences with her role as Aurora in Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty. Her breathtaking grace helped bring ballet to new audiences. In 1949, she toured the United States and became an instant celebrity. Her status as a ballet great arrived at the time most of her peers thought she would retire. In 1961 she danced with the great Rudolf Nureyev. Their partnership lasted until her retirement in 1979 and is still the greatest the ballet world has witnessed. They became lifelong friends. Fonteyn was, incredibly, 59 years old when she retired. She spent her final years living with her diplomat husband in Panama. -

The Late John Lanchbery Was Commissioned by Rudolf Nureyev to Arrange the Score for His Production of Don Quixote

Olivia Bell, 2007 Photography David Kelly MUSIC NOTE The late John Lanchbery was commissioned by Rudolf Nureyev to arrange the score for his production of Don Quixote. Here, Lanchbery explains his approach to the music. Conductor John Lanchbery, 1997 Photography Jim McFarlane In Russia in the second half of the 19th century, unadventurous, and just occasionally uninteresting. Like the scores for all 19th-century ballets that have the growth and popularity of the arts resulted in the His unending fund of melody was at its best in waltz- stayed in the Russian repertoire, Don Quixote has long immigration of a number of non-Russian musicians time, obviously because of his early life in Vienna; ago been tinkered with, added to and subtracted from who served a useful purpose until such time as the when in doubt he wrote in this rhythm, and it is fun to without mercy. When Nureyev commissioned me to do great Russian school of composers came into force. note that in his tragic ballet La Bayadère, a story of a completely new version of it for (coincidentally) the fatal snake-bite, unrequited love and a haunted temple Vienna Opera House in 1966, I therefore suffered no In the ballet of the time the music had above all to be in mythological India, the best musical moment is pangs of conscience in trying to improve the hotch- melodic, easily remembered, and simple in its form when a corps de ballet of beautiful Hindu lady-ghosts potch which has survived as Minkus’ score. I adapted and rhythmic pattern. -

The Australian Ballet 1 2 Swan Lake Melbourne 23 September– 1 October

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 1 2 SWAN LAKE MELBOURNE 23 SEPTEMBER– 1 OCTOBER SYDNEY 2–21 DECEMBER Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Rider Above: Leanne Stojmenov. Photography Branco Gaica Luke Ingham and Miwako Kubota. Photography Branco Gaica 4 COPPÉLIA NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dame Peggy van Praagh’s fingerprints are on everything we do at The Australian Ballet. How lucky we are to have been founded by such a visionary woman, and to live with the bounty of her legacy every day. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in her glorious production of Coppélia, which she created for the company in 1979 with two other magnificent artists: director George Ogilvie and designer Kristian Fredrikson. It was her parting gift to the company and it remains a jewel in the crown of our classical repertoire. Dame Peggy was a renowned Swanilda, and this was her second production of Coppélia. Her first was for the Borovansky Ballet in 1960; it was performed as part of The Australian Ballet’s first season in 1962, and was revived in subsequent years. When Dame Peggy returned to The Australian Ballet from retirement in 1978 she began to prepare this new production, which was to be her last. It is a timeless classic, and I am sure it will be performed well into the company’s future. Dame Peggy and Kristian are no longer with us, but in 2016 we had the great pleasure of welcoming George Ogilvie back to the company to oversee the staging of this production. George and Dame Peggy delved into the original Hoffmann story, layering this production with such depth of character and theatricality. -

91 Nureyev Remembers Margot

Sunday Telegraph February 24 1991 She was the greatest dancer of our epoch Photo Stephen Lock Rudolf Nureyev mourns his partner and lifelong friend, Dame Margot Fonteyn, prima ballerina assoluta, who died on Thursday aged 71. Below Dame Alicia Markova, Dame Ninette de Valois and Sir Kenneth MacMillan add their tributes MY PARTNERSHIP with Margot was without doubt the most important of my life. Performing with her was intoxicating, and it has been my greatest piece of good fortune to have met and become her friend as well as her partner. Margot had a catalystic effect on me. I had been at the Kirov Ballet and danced with 11 ballerinas there; then when I came to the West I partnered Yvette Chauviré and Rosella Hightower. I was about to go the United States, in fact, when Margot invited me to go to her at the Royal Ballet. Somehow I felt a call to change my plans. It was a crucial time. I was 23 and that meeting coloured my whole life. The last time I spoke to her was four days ago, when i rang her to talk about my tour here in America. She was always curious about what I was doing. To cheer her up I told her that I was conducting for the first time. She was delighted, and giggled at that. Then I called her yesterday [Wednesday] because it was my last performance in Salt Lake city and I wanted to brag about it to her. But she was asleep and I couldn’t talk to her - she was under very heavy sedation.