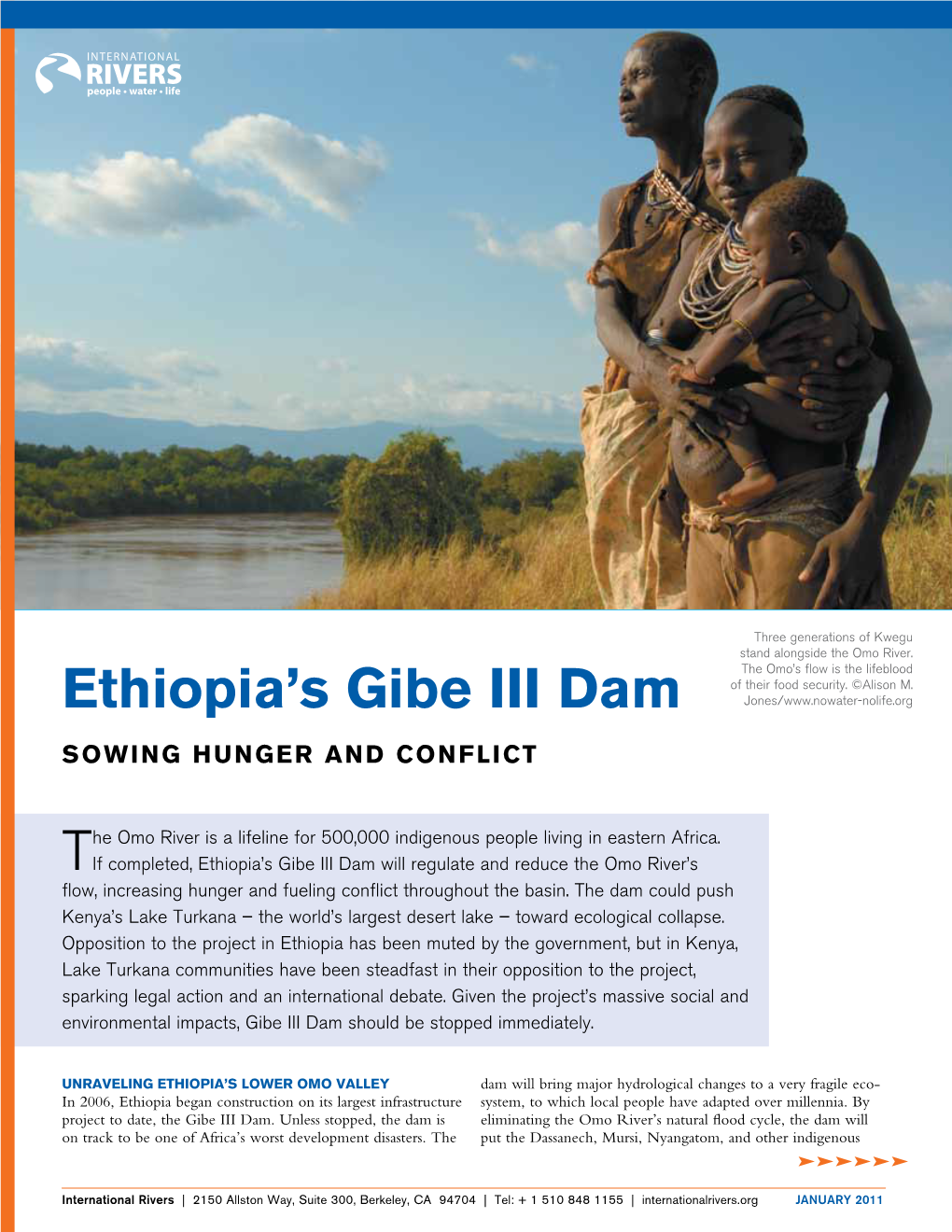

Ethiopials Gibe III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outcomes of the EU Horizon 2020 DAFNE PROJECT the Omo

POLICY BRIEF October 2020 Outcomes of the EU Horizon 2020 DAFNE PROJECT The Omo-Turkana River Basin Progress towards cooperative frameworks KEY POLICY MESSAGES The OTB has reached a stage of pivotal importance for future development; the time to establish a cooperative framework on water governance is now. Transparency and accountability must be improved in order to facilitate the sharing of data and information, increasing trust and reducing the perception of risk. Benefit-sharing which extends beyond energy could enhance regional integration and improve sustainable development within the basin . THE OMO-TURKANA RIVER BASIN potential for hydropower and irrigation schemes that are, if scientifically and equitably managed, crucial to lift millions within and outside the basin out of extreme poverty; this has led to transboundary cooperation in recent years. This policy brief is derived from research conducted under the €5.5M four-year EU Horizon 2020 and Swiss funded ‘DAFNE’ project which concerns the promotion of integrated and adaptive water resources management, explicitly addressing the WEF Nexus and aiming to promote a sustainable economy in regions where new infrastructure and expanding The Omo-Turkana River Basin (OTB) – for the agriculture has to be balanced with social, purposes of the DAFNE Project – comprises of economic and environmental needs. The project two main water bodies: the Omo River in takes a multi- and interdisciplinary approach to Ethiopia and Lake Turkana which it drains into. the formation of a decision analytical While the Omo River lies entirely within Ethiopian territory, Lake Turkana is shared by framework (DAF) for participatory and both Kenya and Ethiopia, with the majority of integrated planning, to allow the evaluation of Lake Turkana residing within Kenya. -

Paranthropus Boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Research Biological Sciences Fall 11-28-2007 Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A. Wood George Washington University Paul J. Constantino Biological Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/bio_sciences_faculty Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Wood B and Constantino P. Paranthropus boisei: Fifty years of evidence and analysis. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 50:106-132. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 50:106–132 (2007) Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard Wood* and Paul Constantino Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 KEY WORDS Paranthropus; boisei; aethiopicus; human evolution; Africa ABSTRACT Paranthropus boisei is a hominin taxon ers can trace the evolution of metric and nonmetric var- with a distinctive cranial and dental morphology. Its iables across hundreds of thousands of years. This pa- hypodigm has been recovered from sites with good per is a detailed1 review of half a century’s worth of fos- stratigraphic and chronological control, and for some sil evidence and analysis of P. boi se i and traces how morphological regions, such as the mandible and the both its evolutionary history and our understanding of mandibular dentition, the samples are not only rela- its evolutionary history have evolved during the past tively well dated, but they are, by paleontological 50 years. -

Taming the Intractable Inter-Ethnic Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-3 Issue-7, July-2018 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE ISSN-2213-1356 www.ijirk.com TAMING THE INTRACTABLE INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICT IN THE ILEMI TRIANGLE PETERLINUS OUMA ODOTE, PHD Abstract This article provides an overview of the historical trends of conflict in the Ilemi triangle, exploring the issues, the nature, context and dynamics of these conflicts. The author endeavours to deepen the understanding of the trends of conflict. A consideration on the discourse on the historical development is given attention. The article’s core is conflict between the five ethnic communities that straddle this disputed triangle namely: the Didinga and Toposa from South Sudan; the Nyangatom, who move around South Sudan and Ethiopia; the Dassenach, who have settled East of the Triangle in Ethiopia; and the Turkana in Kenya. The article delineates different factors that promote conflict in this triangle and how these have impacted on pastoralism as a way of livelihood for the five communities. Lastly, the article discusses the possible ways to deal with the intractable conflict in the Ilemi Triangle. Introduction Ilemi triangle is an arid hilly terrain bordering Kenya, South Sudan and Ethiopia, that has hit the headlines and catapulted onto the international centre stage for the wrong reasons in the recent past. Retrospectively, the three countries have been harshly criticized for failure to contain conflict among ethnic communities that straddle this contested area. Perhaps there is no better place that depicts the opinion that the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must than the Ilemi does. -

Lake Turkana and the Lower Omo the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Account for 50% of Kenya’S Livestock Production (Snyder, 2006)

Lake Turkana & the Lower Omo: Hydrological Impacts of Major Dam & Irrigation Development REPORT African Studies Centre Sean Avery (BSc., PhD., C.Eng., C. Env.) © Antonella865 | Dreamstime © Antonella865 Consultant’s email: [email protected] Web: www.watres.com LAKE TURKANA & THE LOWER OMO: HYDROLOGICAL IMPACTS OF MAJOR DAM & IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENTS CONTENTS – VOLUME I REPORT Chapter Description Page EXECUTIVE(SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................1! 1! INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 12! 1.1! THE(CONTEXT ........................................................................................................................................ 12! 1.2! THE(ASSIGNMENT .................................................................................................................................. 14! 1.3! METHODOLOGY...................................................................................................................................... 15! 2! DEVELOPMENT(PLANNING(IN(THE(OMO(BASIN ......................................................................... 18! 2.1! INTRODUCTION(AND(SUMMARY(OVERVIEW(OF(FINDINGS................................................................... 18! 2.2! OMO?GIBE(BASIN(MASTER(PLAN(STUDY,(DECEMBER(1996..............................................................19! 2.2.1! OMO'GIBE!BASIN!MASTER!PLAN!'!TERMS!OF!REFERENCE...........................................................................19! -

Lieberman 2001E.Pdf

news and views Another face in our family tree Daniel E. Lieberman The evolutionary history of humans is complex and unresolved. It now looks set to be thrown into further confusion by the discovery of another species and genus, dated to 3.5 million years ago. ntil a few years ago, the evolutionary history of our species was thought to be Ureasonably straightforward. Only three diverse groups of hominins — species more closely related to humans than to chim- panzees — were known, namely Australo- pithecus, Paranthropus and Homo, the genus to which humans belong. Of these, Paran- MUSEUMS OF KENYA NATIONAL thropus and Homo were presumed to have evolved between two and three million years ago1,2 from an early species in the genus Australopithecus, most likely A. afarensis, made famous by the fossil Lucy. But lately, confusion has been sown in the human evolutionary tree. The discovery of three new australopithecine species — A. anamensis3, A. garhi 4 and A. bahrelghazali5, in Kenya, Ethiopia and Chad, respectively — showed that genus to be more diverse and Figure 1 Two fossil skulls from early hominin species. Left, KNM-WT 40000. This newly discovered widespread than had been thought. Then fossil is described by Leakey et al.8. It is judged to represent a new species, Kenyanthropus platyops. there was the finding of another, as yet poorly Right, KNM-ER 1470. This skull was formerly attributed to Homo rudolfensis1, but might best be understood, genus of early hominin, Ardi- reassigned to the genus Kenyanthropus — the two skulls share many similarities, such as the flatness pithecus, which is dated to 4.4 million years of the face and the shape of the brow. -

Lake Turkana National Parks - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Lake Turkana National Parks - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2017 (archived) Finalised on 26 October 2017 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Lake Turkana National Parks. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Lake Turkana National Parks عقوملا تامولعم Country: Kenya Inscribed in: 1997 Criteria: (viii) (x) The most saline of Africa's large lakes, Turkana is an outstanding laboratory for the study of plant and animal communities. The three National Parks serve as a stopover for migrant waterfowl and are major breeding grounds for the Nile crocodile, hippopotamus and a variety of venomous snakes. The Koobi Fora deposits, rich in mammalian, molluscan and other fossil remains, have contributed more to the understanding of paleo-environments than any other site on the continent. © UNESCO صخلملا 2017 Conservation Outlook Critical Lake Turkana’s unique qualities as a large lake in a desert environment are under threat as the demands for water for development escalate and the financial capital to build major dams becomes available. Historically, the lake’s level has been subject to natural fluctuations in response to the vicissitudes of climate, with the inflow of water broadly matching the amount lost through evaporation (as the lake basin has no outflow). The lake’s major source of water, Ethiopia’s Omo River is being developed with a series of major hydropower dams and irrigated agricultural schemes, in particular sugar and other crop plantations. -

Diversification of African Tree Frogs (Genus Leptopelis) in the Highlands of Ethiopia

Received: 27 August 2017 | Revised: 25 February 2018 | Accepted: 12 March 2018 DOI: 10.1111/mec.14573 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diversification of African tree frogs (genus Leptopelis) in the highlands of Ethiopia Jacobo Reyes-Velasco1 | Joseph D. Manthey1 | Xenia Freilich2 | Stephane Boissinot1 1New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, UAE Abstract 2Department of Biology, Queens College, The frog genus Leptopelis is composed of ~50 species that occur across sub-Saharan City University of New York, Flushing, NY, Africa. The majority of these frogs are typically arboreal; however, a few species USA have evolved a fossorial lifestyle. Most species inhabit lowland forests, but a few Correspondence species have adapted to high elevations. Five species of Leptopelis occupy the Ethio- Stephane Boissinot, New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, UAE. pian highlands and provide a good opportunity to study the evolutionary transition Email: [email protected] from an arboreal to a fossorial lifestyle, as well as the diversification in this biodiver- sity hot spot. We sequenced 14 nuclear and three mitochondrial genes, and gener- ated thousands of SNPs from ddRAD sequencing to study the evolutionary relationships of Ethiopian Leptopelis. The five species of highland Leptopelis form a monophyletic group, which diversified during the late Miocene and Pliocene. We found strong population structure in the fossorial species L. gramineus, with levels of genetic differentiation between populations similar to those found between arbo- real species. This could indicate that L. gramineus is a complex of cryptic species. We propose that after the original colonization of the Ethiopian highlands by the ancestor of the L. -

Flaked Stones and Old Bones: Biological and Cultural Evolution at the Dawn of Technology

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 47:118–164 (2004) Flaked Stones and Old Bones: Biological and Cultural Evolution at the Dawn of Technology Thomas Plummer* Department of Anthropology, Queens College, CUNY, and New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, Flushing, New York 11367 KEY WORDS Oldowan; Plio-Pleistocene; Africa; early Homo ABSTRACT The appearance of Oldowan sites ca. 2.6 predatory guild may have been moderately high, as they million years ago (Ma) may reflect one of the most impor- probably accessed meaty carcasses through hunting and tant adaptive shifts in human evolution. Stone artifact confrontational scavenging, and hominin-carnivore com- manufacture, large mammal butchery, and novel trans- petition appears minimal at some sites. It is likely that port and discard behaviors led to the accumulation of the both Homo habilis sensu stricto and early African H. first recognized archaeological debris. The appearance of erectus made Oldowan tools. H. habilis sensu stricto was the Oldowan sites coincides with generally cooler, drier, more encephalized than Australopithecus and may fore- and more variable climatic conditions across Africa, prob- shadow H. erectus in lower limb elongation and some ably resulting in a net decrease in woodland foods and an thermoregulatory adaptations to hot, dry climatic condi- increase in large mammal biomass compared to the early tions. H. erectus was large and wide-ranging, had a high and middle Pliocene. Shifts in plant food resource avail- total energy expenditure, and required a high-quality diet. ability may have provided the stimulus for incorporating Reconstruction of H. erectus reproductive energetics and new foods into the diet, including meat from scavenged socioeconomic organization suggests that reproductively carcasses butchered with stone tools. -

Delimitation of the Elastic Ilemi Triangle: Pastoral Conflicts and Official Indifference in the Horn of Africa

Delimitation Of The Elastic Ilemi Triangle: Pastoral Conflicts and Official Indifference in the Horn Of Africa NENE MBURU ABSTRACT This article observes that although scholars have addressed the problem of the inherited colonial boundaries in Africa, there are lacunae in our knowledge of the complexity of demarcating the Kenya-Sudan-Ethiopia tri-junctional point known as the Ilemi Triangle. Apart from being a gateway to an area of Sudan rich in unexplored oil reserves, Ilemi is only significant for its dry season pastures that support communities of different countries. By analyzing why, until recently, the Ilemi has been ‘unwanted’ and hence not economically developed by any regional government, the article aims to historically elucidate differences of perception and significance of the area between the authorities and the local herders. On the one hand, the forage-rich pastures of Ilemi have been the casus belli (cause for war) among transhumant communities of Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya, and an enigma to colonial surveyors who could not determine their ‘ownership’ and extent. On the other hand, failure to administer the region in the last century reflects the lack of attractiveness to the authorities that have not agreed on security and grazing arrangements for the benefit of their respective nomadic populations. This article places the disputed ‘triangle’ of conflict into historical, anthropological, sociological and political context. The closing reflections assess the future of the dispute in view of the current initiative by the USA to end the 19-year-old civil war in Sudan and promote the country’s relationship with her neighbors particularly Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia. -

P0249-P0262.Pdf

THE CONDOR VOLUME 57 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER. 19.55 NUMBER 5 A SYSTEMATIC REVISION AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE SHINING SUNBIRD OF AFRICA By JOHN G. WILLIAMS The ,Shining Sunbird (Cinnyris habessinicus Hemprich and Ehrenberg) has a com- paratively restricted distribution in the northeastern part of the Ethiopian region. It occurs sporadically from the northern districts of Kenya Colony and northeastern Uganda northward to Saudi Arabia, but it apparently is absent from the highlands of Ethiopia (Abyssinia) above 5000 feet. The adult male is one of the most brightly col- ored African sunbirds, the upper parts and throat being brilliant metallic green, often with a golden sheen on the mantle, and the crown violet or blue. Across the breast is a bright red band, varying in width, depth of color, and brilliance in the various races, bordered on each side by yellow pectoral tufts; the abdomen is black. The female is drab gray or brown and exhibits a well-marked color cline, the most southerly birds being pale and those to the northward becoming gradually darker and terminating with the blackish-brown female of the most northerly subspecies. In the present study I am retaining, with some reluctance, the genus Cinnyris for the speciesunder review. I agree in the main with Delacour’s treatment of the group in his paper ( 1944) “A Review of the Family Nectariniidae (Sunbirds) ” and admit that the genus Nectarinia, in its old, restricted sense, based upon the length of the central pair of rectrices in the adult male, is derived from a number of different stocks and is ur+ sound. -

Land and Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle of East Africa

Land and Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle of East Africa By Maurice N. Amutabi Abstract Insecurity among the nations of the Horn of Africa is often concentrated in the nomadic pastoralist areas. Why? Is the pastoralist economy, which revolves around livestock, raiding and counter-raiding to blame for the violence? Why are rebel movements in the Horn, such the Lord‟s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in Ethiopia, several warlords in Somalia, etc, situated in nomadic pastoralist areas? Is the nomadic lifestyle to blame for lack of commitment to the ideals of any one nation? Why have the countries in the Horn failed to absorb and incorporate nomadic pastoralists in their structures and institutions, forty years after independence? Utilizing a political economy approach, this article seeks to answer these questions, and more. This article is both a historical and philosophical interrogation of questions of nationhood and nationalism vis-à-vis the transient or mobile nature that these nomadic pastoralist “nations” apparently represent. It scrutinizes the absence of physical and emotional belonging and attachment that is often displayed by these peoples through their actions, often seen as unpatriotic, such as raiding, banditry, rustling and killing for cattle. The article assesses the place of transient and migratory ethnic groups in the nation-state, especially their lack of fixed abodes in any one nation-state and how this plays out in the countries of the region. I pay special attention to cross-border migratory ethnic groups that inhabit the semi-desert areas of the Sudan- Kenya-Ethiopia-Somalia borderlines as case studies. -

The Turkana Grazing Factor in Kenya-South Sudan Ilemi Triangle Border Dispute

International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) ISSN: 2394-4404 Volume 6 Issue 8, August 2019 The Turkana Grazing Factor In Kenya-South Sudan Ilemi Triangle Border Dispute James Kiprono Kibon PhD Candidate, Department of International Relations, United States International University-Africa , Nairobi, Kenya Abstract: This article examines the place of the customary grazing grounds of the Turkana, which was one of the most salient factors in the making of what is today the Kenya- South Sudan boundary. It is argued in this article that while the making of the Kenya-South Sudan boundary was driven by British colonial interests, the issue of the customary grazing grounds of the Turkana was major consideration in the actual demarcation. The Kenya-South Sudan boundary was the outcome of a deliberate effort to delimit the customary grazing grounds of the Turkana in the Ilemi area between 1914 and 1950. The northward evolution of the Kenya-South Sudan border from the Uganda Line reflected in the series of boundary adjustments gave birth to the disputed Ilemi Triangle border. The boundary changes were majorly driven by the quest to determine the northern extent of the customary grazing grounds of the Turkana, based on the provision of a second alternative boundary option by 1914 Uganda Order in Council. It is argued in this article that unlike other Africa’s colonial boundaries, the Kenya-South Sudan boundary was conceived with the objective of placing all the customary grazing grounds of the Turkana in Uganda and Kenya. This article therefore, argues that just as Turkana grazing grounds was key crucial factor in the emergence of the Kenya-South Sudan boundary, it is also central to the Ilemi Triangle border dispute.