Reptiles.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rubber Boas in Radium Hot Springs: Habitat, Inventory, and Management Strategies

Rubber Boas in Radium Hot Springs: Habitat, Inventory, and Management Strategies ROBERT C. ST. CLAIR1 AND ALAN DIBB2 19809 92 Avenue, Edmonton, AB, T6E 2V4, Canada, email [email protected] 2Parks Canada, Box 220, Radium Hot Springs, BC, V0A 1M0, Canada Abstract: Radium Hot Springs in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia is home to a population of rubber boas (Charina bottae). This population is of ecological and physiological interest because the hot springs seem to be a thermal resource for the boas, which are near the northern limit of their range. This population also presents a dilemma to park management because the site is a major tourist destination and provides habitat for the rubber boa, which is listed as a species of Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). An additional dilemma is that restoration projects, such as prescribed logging and burning, may increase available habitat for the species but kill individual snakes. Successful management of the population depends on monitoring the population, assessing the impacts of restoration strategies, and mapping both summer and winter habitat. Hibernation sites may be discovered only by using radiotelemetry to follow individuals. Key Words: rubber boa, Charina bottae, Radium Hot Springs, hot springs, snakes, habitat, restoration, Kootenay National Park, British Columbia Introduction The presence of rubber boas (Charina bottae) at Radium Hot Springs in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia (B.C.) presents some unusual challenges for wildlife managers because the site is a popular tourist resort and provides habitat for the species, which is listed as a species of Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC 2004). -

Tantilla Hobartsmithi Taylor Smith's Black-Headed Snake

318.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE TANTILLA HOBARTSMITHI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. CHARLESJ. COLEANDLAURENCEM. HARDY. 1983. Tantilla hobartsmithi. Tantilla hobartsmithi Taylor Smith's black-headed snake Tantilla nigriceps (not of Kennicott): Van Denburgh and Slevin, 5MM 1913:423-424. ~ Tantilla planiceps (not of Blainville): Stejneger and Barbour, 1917: 105 (part). FIGURE2. Color pattern of head and neck of Tantilla hobart• Tantilla nigriceps eiseni (not of Stejneger): Woodbury, 1931:107• smithi, American Museum of Natural History 107377 (from Cole 108. and Hardy, 1981:210). Tantllla atriceps (not of Giinther): Taylor, "1936" [1937]:339-340 (part). Tantilla hobartsmithi Taylor, "1936" [1937]:340-342. Type-lo• in 1-3 rows (minimum) approximately encircling spinose midsec• cality, "near La Posa, 10 mi. northwest of Guaymas," So• tion of hemipenis; supralabials 7; infralabials 6; naris in upper nora, Mexico (Taylor, "1936" [1937]:340-341). The holotype, half of nasal; postoculars usually 2; temporals 1 + 1; mental usu• University of Illinois Museum of Natural History 25066, an ally touching anterior pair of genials. Most similar to T. atriceps; adult male (examined by authors), was collected by Edward differing strikingly in hemipenis" (Cole and Hardy, 1981:221). H. Taylor, the night of 3 July 1934. • DESCRIPTIONS. See Cole and Hardy (1981) for a redescrip• Tantilla utahensis Blanchard, 1938:372-373. Type-locality, "St. tion of the holotype (including description of hemipenis); general George, Washington County, Utah" (Blanchard, 1938:372). descriptions of size, coloration, hemipenes, scutellation, maxil• The holotype, California Academy of Sciences 55214, an adult lae, and chromosomes; and analyses of geographic variation. female (examined by authors), was collected by V. -

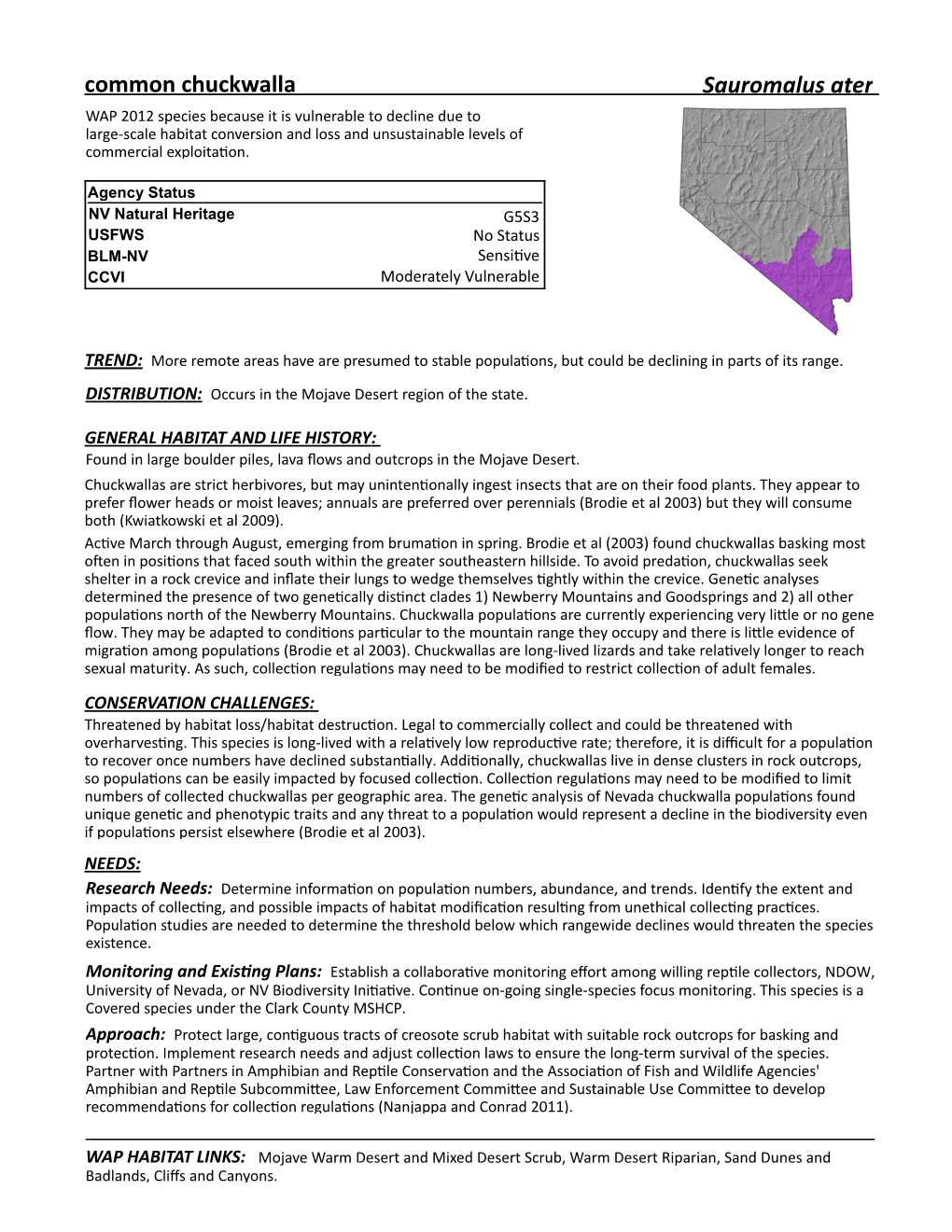

Nevada Department of Wildlife

STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Wildlife Diversity Division 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Ste 120 • Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 688-1500 Fax (775) 688-1697 #18 B MEMORANDUM August 30, 2018 To: Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners, County Advisory Boards to Manage Wildlife, and Interested Publics From: Jennifer Newmark, Administrator, Wildlife Diversity Division Title: Commission General Regulation 479, Rosy Boa Reptile, LCB File No. R152- 18 – Wildlife Diversity Administrator Jennifer Newmark and Wildlife Diversity Biologist Jason Jones – For Possible Action Description: The Commission will consider adopting a regulation relating to amending Chapter 503 of the Nevada Administrative Code (NAC). This amendment would revise the scientific name of the rosy boa, which is classified as a protected reptile, from Lichanura trivirgata to Lichanura orcutti. This name change is needed due to new scientific studies that have split the species into two distinct entities, one that occurs in Nevada and one that occurs outside the state. Current NAC protects the species outside Nevada rather than the species that occurs within Nevada. The Commission held a workshop on Aug. 10, 2018, and the Commission directed the Department to move forward with an adoption hearing. Summary: A genetics study in 2008 by Woods et al. split the rosy boa into two distinct species – the three- lined boa (Lichanura trivirgata) and the rosy boa (Lichanura orcutti). This split was formally recognized in 2017 by the Committee on Standard English and Scientific Names by the Society of the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Three-lined boas, Lichanura trivirgata, occur in Baja California, Southern Arizona and Sonora Mexico, while the rosy boa, Lichanura orcutti occur in Nevada, parts of California and northern Arizona. -

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care Sheets Are Often An

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care sheets are often an excellent starting point for learning more about the biology and husbandry of a given species, including their housing/enclosure requirements, temperament and handling, diet , and other aspects of care. MAHS itself has created many such care sheets for a wide range of reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates we believe to have straightforward care requirements, and thus make suitable family and beginner’s to intermediate level pets. Some species with much more complex, difficult to meet, or impracticable care requirements than what can be adequately explained in a one page care sheet may be multiple pages. We can also provide additional links, resources, and information on these species we feel are reliable and trustworthy if requested. If you would like to request a copy of a care sheet for any of the species listed below, or have a suggestion for an animal you don’t see on our list, contact us to let us know! Unfortunately, for liability reasons, MAHS is unable to create or publish care sheets for medically significant venomous species. This includes species in the families Crotilidae, Viperidae, and Elapidae, as well as the Helodermatidae (the Gila Monsters and Mexican Beaded Lizards) and some medically significant rear fanged Colubridae. Those that are serious about wishing to learn more about venomous reptile husbandry that cannot be adequately covered in one to three page care sheets should take the time to utilize all available resources by reading books and literature, consulting with, and working with an experienced and knowledgeable mentor in order to learn the ropes hands on. -

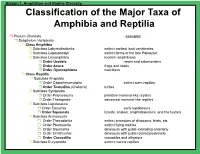

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Wildlife Item 09 CGR-479

#7 C STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Wildlife Diversity Division 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Ste 120 • Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 688-1500 Fax (775) 688-1697 MEMORANDUM July 23, 2018 To: Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners, County Advisory Boards to Manage Wildlife, and Interested Publics From: Jennifer Newmark, Administrator, Wildlife Diversity Division Title: Commission General Regulation 479, Scientific Name Change of the Rosy Boa, a Protected Reptile, LCB File No. 152-18 – For Possible Action/Public Comment Allowed Description: The Commission will consider and may take action to change the scientific name of the rosy boa, protected under Nevada Administrative Code 503.080, from Lichanura trivirgata, to Lichanura orcutti due to recent studies that have updated the taxonomy of the species. Summary: A genetics study in 2008 by Woods et al. split the rosy boa into two distinct species – the three- lined boa (Lichanura trivirgata) and the rosy boa (Lichanura orcutti). This split was formally recognized in 2017 by the Committee on Standard English and Scientific Names by the Society of the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Three-lined boas, Lichanura trivirgata, occur in Baja California, Southern Arizona and Sonora Mexico, while the rosy boa, Lichanura orcutti occur in Nevada, parts of California and northern Arizona. As currently listed, NAC 503.080 protects the three-lined boa, Lichanura trivirgata, a species that does not occur in Nevada. Recognizing the taxonomic change will ensure the species presumed to occur in Nevada, the rosy boa (Lichanura orcutti) will remain protected. The Department is recommending the Commission change the name of the rosy boa listed under NAC 503.080 from Lichanura trivirgata to Lichanura orcutti to protect the correct native species occurring in the state. -

Monitoring Results for Reptiles, Amphibians and Ants in the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC) 2002

Monitoring Results for Reptiles, Amphibians and Ants in the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC) 2002 Summary Report Prepared for: The Nature Reserve of Orange County – Lyn McAfee The Nature Conservancy – Trish Smith U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WESTERN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH CENTER Monitoring Results for Reptiles, Amphibians and Ants in the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC) 2002 By Adam Backlin1, Cindy Hitchcock1, Krista Pease2 and Robert Fisher2 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WESTERN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH CENTER Annual Report Prepared for: The Nature Reserve of Orange County The Nature Conservancy 1San Diego Field Station-Irvine Office USGS Western Ecological Research Center 2883 Irvine Blvd. Irvine, CA 92602 2San Diego Field Station-San Diego Office USGS Western Ecological Research Center 5745 Kearny Villa Road, Suite M San Diego, CA 92123 Sacramento, California 2003 ii U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, SECRETARY U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, or brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information, contact: Center Director Western Ecological Research Center U.S. Geological Survey 7801 Folsom Blvd., Suite 101 Sacramento, CA 95826 iii Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 1 Research Goals .................................................................................................................. -

Life History Account for Smith's Black-Headed Snake

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group SMITH'S BLACK-HEADED SNAKE Tantilla hobartsmithi Family: COLUBRIDAE Order: SQUAMATA Class: REPTILIA R069 Written by: R. Duke Reviewed by: T. Papenfuss Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Staff, February 2008 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE AND SEASONALITY Smith's black-headed snake is an uncommon species found in California in Inyo, San Bernardino, Kings and Tulare cos. Recently redescribed (Cole and Hardy 1981), the species may be more widespread and common but few data are available. May also be present in Kern and Fresno cos., but there are no verified records. Elsewhere, the species ranges patchily throughout the southwest and into Mexico. These secretive, fossorial snakes are found in a variety of arid habitats, including desert riparian, pine-juniper, sagebrush, alkali scrub, Joshua tree and perennial grass. Ranges up to 1440 m (4750 ft) in the Kingston Mts, San Bernardino Co. (Stebbins 1954, Banta 1960, Cole and Hardy 1981, 1983). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: The few records available indicate a preference for invertebrate prey. Beetle larvae, and centipedes have been reported (Minton 1959). Millipedes, spiders and other invertebrates are probably taken as well. Cover: Fossorial. Friable, organic or sandy soil probably required. The species is often found under loose boards, logs, wood, rocks and fallen shrubs. Reproduction: Habitat requirements are unknown. Eggs are probably laid in crevices, rotting logs, or abandoned mammal burrows. Water: No data. More common near water sources. Pattern: Prefers moist niches in otherwise arid or semi-arid habitats, with debris, and friable soil. -

Critter Twitter June 6-10 & July 11-15, 2011

Critter Twitter June 6-10 & July 11-15, 2011 Monday-Visual Communication Time K-1st Grade 2nd-3rd Grade 4th-6th Grade 8:45 Check in Check in Check in Talk about how animals Talk about how animals Talk about how animals 9:00 communicate visually communicate visually communicate visually Keeper talk & feeding-BRC 9:30 Snack aviary Game-Clothespin Tag 10:00 Game-Zookeeper Snack AP-bearded dragon & ferret 10:30 AP-milk snake and opossum Game-Clothespin Tag Snack Craft-trace body on butcher paper, add a visual 11:00 Craft-Nature Notebook Craft-Nature Notebook communication adaptation Draw picture of animal who Draw picture of animal who Zoo tour-look for visual 11:30 communicates visually communicates visually communication signs 11:50 Plaza-1/2 day campers depart Plaza-1/2 day campers depart Plaza-1/2 day campers depart 12:00 Lunch at Treetops Lunch at Treetops Lunch at Treetops 12:45 Clean up/Restroom break Clean up/Restroom break Clean up/Restroom break 1:00 AP-bearded dragon & ferret Game- Game-Clump 1:30 Game-Clump AP-bearded dragon & ferret BTS-Giraffe 2:00 Snack Snack AP-milk snake and opossum Craft-trace body on butcher paper, add a visual 2:30 BTS-Giraffe communication adaptation Snack 3:00 Craft-Giraffe headband BTS-Giraffe Craft-Nature Notebook Draw picture of animal who 3:30 Game-Rainbow Tag Game-Rainbow Tag communicates visually 3:45 Plaza for pick-up Plaza for pick-up Plaza for pick-up 4:00- 5:30 Extended day care Extended day care Extended day care Tuesday-Auditory Communication Time K-1st Grade 2nd-3rd Grade 4th-6th Grade 8:45 -

Rosy Boas Can Be Housed in a 10 Gallon Zilla® Critter Cage® Product

Husbandry Handbook Housing Housing must be sealed and escape proof. Hatchling Rosy Boas can be housed in a 10 gallon Zilla® Critter Cage® product. Adults will require a minimum of a Rosy Boa 20L Zilla® Critter Cage® product. While Rosy Boas can reach a length of 36", they are terrestrial and don’t need a tall tank. Provide Rosy Boas with substrates that enable burrowing such as Zilla® Lizard Litter. Decorate the tank with driftwood, Lichanura trivirgata rocks, logs and other décor for ample basking and hiding opportunities. Geographical Variation Temperature and Humidity Rosy Boas are one of two species of boidae in the United States, the other being It is important to create a thermal gradient (or a warm side) in the cage/ the Rubber Boa. One very unique characteristic of Rosy Boas is that their color enclosure. This can be done with an appropriate sized Zilla® Heat Mat adhered and patterns vary greatly depending on where they live. Most have lateral striping to the bottom of the tank on one side. Ideal temperatures for Rosy Boas range in two different colors but a few have a reticulated granite pattern. Many experts from 65-75°F on the cool side and 80-85°F on the warm side. Provide a basking can tell exactly where the snake came from just based on its coloration and area on the warm side around 90-95°F. Using a Zilla® Mini Heat & UVB Fixture pattern. Around Morongo Valley, CA, they are striped with bright orange and with a Zilla® 50W Mini Halogen bulb and a Zilla® Desert Mini Compact blue/grey but in the Maricopa Mountains of AZ they are striped with deep brown Fluorescent UVB Bulb will provide the correct heat and UV for your Rosy Boa to and cream white. -

Rubber Boa March 2019

Volume 32/Issue 7 Rubber Boa March 2019 RUBBER BOA INSIDE: Reptiles Heads or Tails? Snakes – Sinister or Sacred? © Tony Iwane CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr © Natalie McNear CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr © Natalie McNear CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr © J. Maughn CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr © J. Maughn CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr Rubber Boa o you know that a boa constrictor lives Rubber boas may be found throughout Idaho in Idaho? Many people are surprised from deserts to pine forests. They need water Dto learn that there is a boa constrictor and downed logs or leaf litter nearby. They are found in our state. It is the rubber boa. Its very shy and will burrow in soil and under logs scientific name is Charina bottae (CHA-ree-na and rocks when frightened. They spend most of BOW-tay). Charina means graceful. This is a the day safe in a burrow and come out at dusk fitting name! Rubber boas are graceful as they or during the night. However, they may venture slide and slither over the ground. out of their burrows on a mild, cloudy day to look for food. Sometimes they are seen basking Rubber boas got their name for how they look in the sun, but this is rare. and feel. They have small scales, and the skin is loose on the body. This gives them the look and Rubber boas kill their prey by constriction just feel of rubber. It is sometimes hard to tell which like larger boas. -

Amphibians & Reptiles Birds Canines & Felines Fish & Rodents Elephants

Adopt-An-Animal Any animal at Fresno Chaffee Zoo can be adopted. Animals that are highlighted green always have a plush available. Animals that are highlighted purple temporarily have a plush option. Animals that are black do not have a corresponding plush. *Animals without a plush can be adopted with any other available plush option. *Some of our animals are not exhibit animals Amphibians & Reptiles Birds Canines & Felines Primates Amphibians American flamingo Canines Apes Siamang Aquatic caecilian Andean condor Fennec fox California tiger salamander Bateleur eagle Red wolf Sumatran orangutan Black-necked stilt Lemurs Frogs African bullfrog Black vulture Felines Red ruffed lemur Bicolored poison dart frog Blue-crowned motmot African lion Ring-tailed lemur Blue poison dart frog Blue-faced honeyeater Black-footed cat Monkeys Dyeing poison frog Blue-throated piping-guan Cheetah Black-and-white colobus monkey Giant waxy tree frog Boat-billed heron Malayan tiger Goeldi's monkey Golfodulcean poison frog Cape thick-knee Serval Golden lion tamarin Green-and-black poison dart frog California brown pelican Lesser spot-nosed guenon Mossy frog Cockatoos Panamanian golden frog Goffin's cockatoo Elephants & Ungulates Sambava tomato frog Lesser sulphur-crested cockatoo Elephants Valley Farm Splashback poison dart frog Long-billed corella African elephant Alpaca White's tree frog Moluccan cockatoo Asian elephant Bourbon red turkey Yellow-banded poison dart frog Rose breasted cockatoo Chickens Newts Sulphur-crested cockatoo Ungulates Orpington chicken