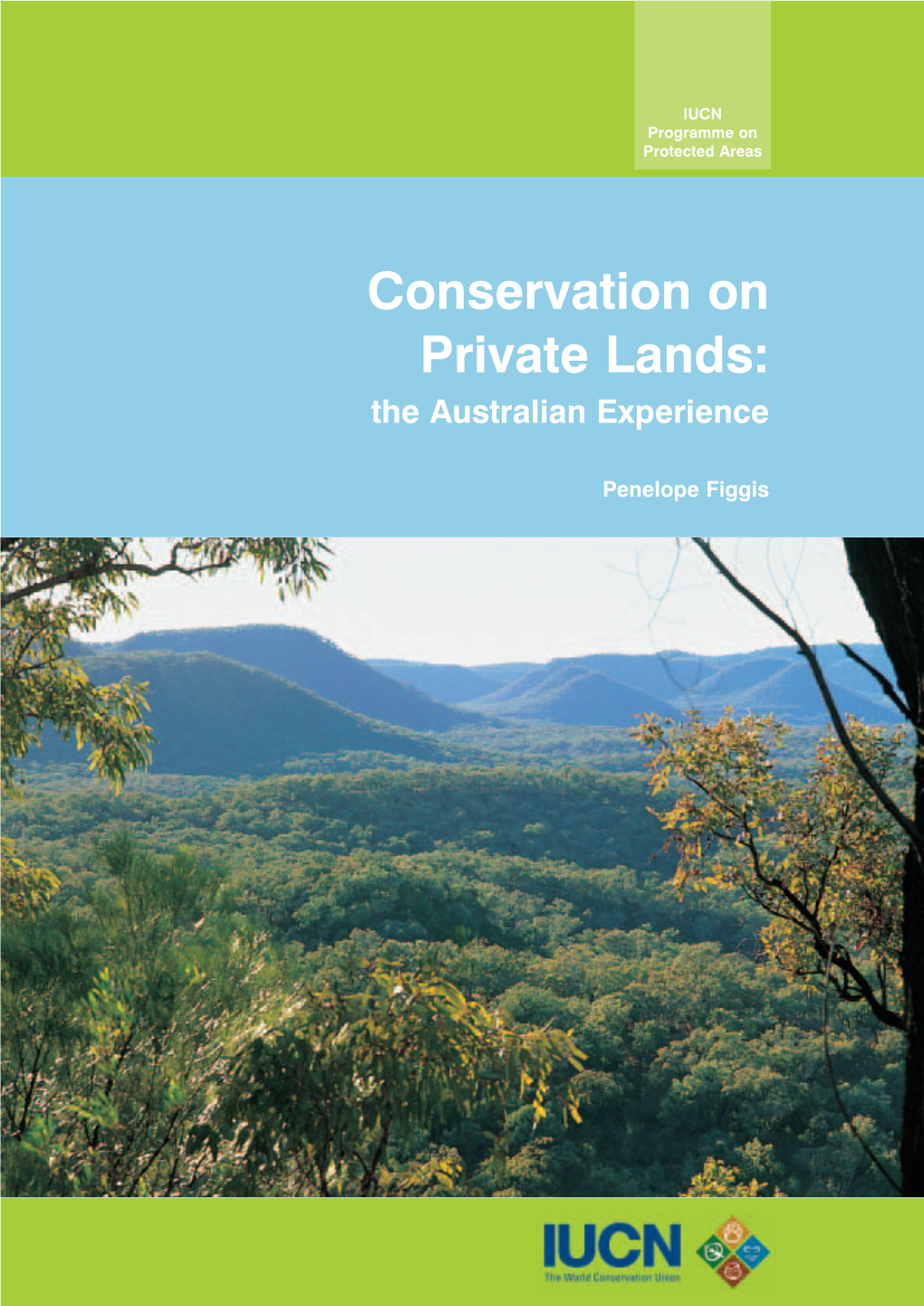

Conservation on Private Lands: the Australian Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019

bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019 Outback extremes Darwin’s legacy Platypus patrol Understanding how climate How a conversation beneath Volunteers brave sub-zero change will impact our western gimlet gums led to the creation temperatures to help shed light Queensland reserves. of Charles Darwin Reserve. on the Platypus of the upper Murrumbidgee River. Bush Heritage acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the places in which we live, work and play. We recognise and respect the enduring relationship they have with their lands and waters, and we pay our respects to elders, past and present. CONTRIBUTORS 1 Ethabuka Reserve, Qld, after rains. Photo by Wayne Lawler/EcoPix Chris Grubb Clare Watson Dr Viki Cramer Bron Willis Amelia Caddy 2 DESIGN Outback extremes Viola Design COVER IMAGE Ethabuka Reserve in far western Queensland. Photo by Lachie Millard / 8 The Courier Mail Platypus control This publication uses 100% post- 10 consumer waste recycled fibre, made Darwin’s legacy with a carbon neutral manufacturing process, using vegetable-based inks. BUSH HERITAGE AUSTRALIA T 1300 628 873 E [email protected] 13 W www.bushheritage.org.au Parting shot Follow Bush Heritage on: few years ago, I embarked on a scientific they describe this work reminds me that we are all expedition through Bush Heritage’s Ethabuka connected by our shared passion for the bush and our Aa Reserve, which is located on the edge of the dedication to seeing healthy country, protected forever. Simpson Desert, in far western Queensland. We were prepared for dry conditions and had packed ten Over the past 27 years, this same passion and days’ worth of water, but as it happened, our visit to dedication has seen Bush Heritage grow from strength- Ethabuka coincided with a rare downpour – the kind to-strength through two evolving eras of leadership of rain that transforms desert landscapes. -

Abhf Summer Nl 05

Bush Heritage News Summer 2005 ABN 78 053 639 115 www.bushheritage.org Lake Eyre.The colours and the In this issue Our latest purchase vastness of the landscape took my Cravens Peak – another bit of the breath away. Rich ochres of every hue and cobalt-blue sky seemed to Anchors in the landscape Outback stretch into infinity. Charles Darwin Reserve weeding bee Bush Heritage’s latest reserve, I was standing on the edge of the Cravens Peak, is ‘just down the Channel Country, that highly metropolitan Melbourne or Sydney) road’ from Ethabuka Reserve in productive region of Queensland and also the most expensive because far-western Queensland but, as famous for fattening cattle, and for of the ‘value’ of the Channel Country. Conservation Programs Manager this reason so far poorly reserved. We still have a great deal of money Paul Foreman points out, this new I contemplated the significance to raise! pastoral lease is very different of Bush Heritage’s buying and protecting some of this valuable Cravens Peak is now our most diverse On my first visit to Cravens Peak ecosystem at Cravens Peak Station, reserve, in both its geomorphology Station in May this year I stood where the Mulligan River plains and biology. It is an exciting acquisition on an outcrop of the Toko Range are still relatively intact. and presents us with an unprecedented and gazed over the source of the management challenge. Mulligan River.This is one of the On 31 October 2005 Cravens Peak headwaters of the immense Cooper became the 21st Bush Heritage Creek system that braids its way reserve. -

Summer 2013 Newsletter

BUSH HERITAGE In this issue 3 Rock‑wallabies unveiled on Yourka 4 Around your reserves 6 Falling for the Fitz‑Stirling NEWS 8 From the CEO Summer 2013 · www.bushheritage.org.au Charting the change Cockatiels bathing at a waterhole on Charles Darwin Reserve, WA. Photograph by Dale Fuller Your Charles Darwin Reserve in Western In a landscape with three times the Under current climate models, the region Australia is situated at the junction of biodiversity of Australia’s tropical rainforests, where the reserve is located is predicted two major bioregions, in a landscape of the animals found in the traps are many and to become rapidly hotter (particularly its extraordinary biodiversity. Its location makes varied, ranging from spiders, to centipedes, summer minimum temperatures) and drier it ideal for a long‑term study into how climate small mammals like dunnarts, geckos and – with an increasing proportion of its rainfall change is impacting native plants and animals. even the occasional brown snake. occurring in the summer months. As the morning sun sheds its first light across Within one of Australia’s only two a subtle landscape of undulating sandplains, internationally recognised biodiversity “It’s at these sort of contact dense mulga scrub and shimmering salt hotspots, Charles Darwin Reserve provides points where you’re going to lakes, Bush Heritage staff and volunteers essential habitat and vital insights into the are already up and on the go on your conservation of thousands of plant and first see the changing ecology Charles Darwin Reserve. animal species. of plants and animals due to At dawn, each of the strategically placed pitfall It’s also ideally located for gathering the effects of climate change.” traps needs to be checked, and the overnight information about the long‑term effects Dr Nic Dunlop, Project Leader, catch recorded and released as quickly of climate change in such a biodiverse area. -

GREAT DESERT SKINK TJAKURA Egernia Kintorei

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory GREAT DESERT SKINK TJAKURA Egernia kintorei Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Vulnerable Photo: Steve McAlpin Description southern sections of the Great Sandy Desert of Western The great desert skink is a large, smooth bodied lizard with an average snout-vent length of 200 mm (maximum of 440 mm) and a body mass of up to 350 g. Males are heavier and have broader heads than females. The tail is slightly longer than the snout-vent length. The upperbody varies in colour between individuals and can be bright orange- brown or dull brown or light grey. The underbody colour ranges from bright lemon- yellow to cream or grey. Adult males often have blue-grey flanks, whereas those of females and juveniles are either plain brown or vertically barred with orange and cream. Known locations of great desert skink. Distribution The great desert skink is endemic to the Australia. Its former range included the Great Australian arid zone. In the Northern Territory Victoria Desert, as far west as Wiluna, and the (NT), most recent records (post 1980) come Northern Great Sandy Desert. from the western deserts region from Uluru- Conservation reserves where reported: Kata Tjuta National Park north to Rabbit Flat in the Tanami Desert. The Tanami Desert and Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Watarrka Uluru populations are both global strongholds National Park and Newhaven Reserve for the species. (managed for conservation by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy). Outside the NT it occurs in North West South Australia and in the Gibson Desert and For more information visit www.denr.nt.gov.au Ecology qualifies as Vulnerable (under criteria C2a(i)) due to: The great desert skink occupies a range of • population <10,000 mature individuals; vegetation types with the major habitat being • continuing decline, observed, projected or sandplain and adjacent swales that support inferred, in numbers; and hummock grassland and scattered shrubs. -

Bush Heritage News Winter 2003

Bush Heritage News Winter 2003 ABN 78 053 639 115 www.bushheritage.org In this issue New land at Liffey Reserve values Carnarvon springs Currumbin Charles Darwin Reserve update Chereninup update the blocks purchased by Bob Brown in receiving the tax deduction now available Another reserve 1990 to become the first Bush Heritage for gifts of this kind, the benefits of reserves. Like these reserves it backs onto which can be spread over five years. at Liffey the Central Plateau World Heritage Area Bush Heritage will manage the property beneath the great dolorite and sandstone along with its neighbouring Liffey In 1992, as Bob Brown was building a escarpment. Majestic trees cling to the reserves.Your valuable donations will fledgling organisation into the Australian walls of the steep-sided valley beneath help cover its modest management costs. Bush Heritage Fund, Dr Judy Henderson the Great Western Tiers.A creek tumbles was buying land. Her motivation, like down over a series of spectacular waterfalls Judy is pleased to have the land protected Bob Brown’s, was to save the magnificent to feed the Liffey River with its platypus for the long term. Bush Heritage is trees on this property in Tasmania from and native fish.This creek gully supports grateful for this generous gift that is a being clear-felled. At the time, Judy a mix of wet sclerophyll and rainforest valuable addition to the land in its care. Henderson was one of the founding species and an abundance of ferns.The directors of Bush Heritage. Bush Heritage is one of the best initiatives area is also home to white goshawks, that I have ever been associated with. -

Hoser, R. T. 2018. New Australian Lizard Taxa Within the Greater Egernia Gray, 1838 Genus Group Of

Australasian Journal of Herpetology 49 Australasian Journal of Herpetology 36:49-64. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) Published 30 March 2018. ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) New Australian lizard taxa within the greater Egernia Gray, 1838 genus group of lizards and the division of Egernia sensu lato into 13 separate genera. RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 1 Jan 2018, Accepted 13 Jan 2018, Published 30 March 2018. ABSTRACT The Genus Egernia Gray, 1838 has been defined and redefined by many authors since the time of original description. Defined at its most conservative is perhaps that diagnosis in Cogger (1975) and reflected in Cogger et al. (1983), with the reverse (splitters) position being that articulated by Wells and Wellington (1985). They resurrected available genus names and added to the list of available names at both genus and species level. Molecular methods have largely confirmed the taxonomic positions of Wells and Wellington (1985) at all relevant levels and their legally available ICZN nomenclature does as a matter of course follow from this. However petty jealousies and hatred among a group of would-be herpetologists called the Wüster gang (as detailed by Hoser 2015a-f and sources cited therein) have forced most other publishing herpetologists since the 1980’s to not use anything Wells and Wellington. Therefore the most commonly “in use” taxonomy and nomenclature by published authors does not reflect the taxonomic reality. This author will not be unlawfully intimidated by Wolfgang Wüster and his gang of law-breaking thugs using unscientific methods to destabilize zoology as encapsulated in the hate rant of Kaiser et al. -

WWF0107 the Web Summer.Indd

THE WEB The national newsletter for the Threatened Species Network WELCOME TO SUMMER 2007 The Threatened Species Network is a community -based program of the Australian Government and WWF-Australia Lord Mayor of Sydney Clover Moore MP, WWF-Australia CEO Greg Bourne and Earth Hour Youth Ambassador Sarah Bishop at the launch of Earth Hour on 15 December 2006. Sarah Bishop will walk from Brisbane to Sydney in early 2007 as a way of voicing young Australians’ concerns about global warming. During the two-month, 1000-kilometre walk, Sarah will exchange ideas and make presentations to communities along the way, illustrating the simple things people can do to make a difference. © WWF/Tanya Lake. COMMUNITY ACTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE By Katherine Howard, TSN Program Officer, WWF-Australia Welcome to the Summer Web! In the last couple of editions we’ve talked about the topic that’s on everyone’s lips – climate change. Here at the TSN we are very excited about an upcoming event called Earth Hour, organised by WWF-Australia and Fairfax Publishing. At 7.30 pm on 31 March, businesses and households all over Sydney will switch off their lights for one hour. Earth Hour is part of a major effort CONTENTS to reduce Sydney’s greenhouse gas pollution by 5% in one year, and will send NATIONAL NEWS a very powerful message that it is possible to take action against global warming. What’s On 2 The threat of climate change needs to be tackled by a two-pronged approach: mitigation and adaptation. We REGIONAL NEWS need to both lower our greenhouse emissions to reduce the extent of climate change (mitigation) and to build SA 3 the resilience of our native species and natural ecosystems to the changed conditions (adaptation).1 The TSN’s Queensland 4 speciality is community-based, on-ground conservation, so we particularly focus on building resilience, but we Arid Rangelands 6 certainly haven’t forgotten how crucial it is to also reduce our emissions of greenhouse gases. -

Environmental Offsets Discussion, (GHD, November 2016)

Appendix 5 Environmental Offsets Discussion, (GHD, November 2016) GHD | Report for Arafura Resources Ltd ‐ Nolans Project Supplement Report, 4322529 Arafura Resources Limited Nolans Project Environmental Offsets Discussion November 2016 GHD | Report for Arafura Resources Limited - Nolans Project, 43/22301 | i Table of contents 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1 2. Environmental offsets under the EPBC Act ...................................................................................2 2.1 What are environmental offsets?.........................................................................................2 2.2 When do EPBC Act offsets apply? ......................................................................................2 2.3 Types of Offsets...................................................................................................................3 2.4 How are EPBC Act offsets determined?..............................................................................4 3. Offset delivery options for the Black-footed Rock-wallaby and Great Desert Skink at the Nolans Project..........................................................................................................................7 4. Future management and monitoring of offsets ..............................................................................9 5. References...................................................................................................................................10 -

World Heritage Papers 7 ; Cultural Landscapes: the Challenges Of

Ferrara 7-couv 12/01/04 17:38 Page 1 7 World Heritage papers7 World Heritage papers Cultural Landscapes: Cultural Landscapes: the Challenges of Conservation of Challenges the Landscapes: Cultural the Challenges of Conservation World Heritage 2002 Shared Legacy, Common Responsibility Associated Workshops 11-12 November 2002 Ferrara - Italy For more information contact: paper; printed on chlorine free Cover paper interior printed on recycled RectoVerso Design by UNESCO World Heritage Centre papers 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Tel : 33 (0)1 45 68 15 71 Fax : 33 (0)1 45 68 55 70 E-mail : [email protected] orld Heritage W http://whc.unesco.org/venice2002 photo:Cover Delta © Studio B&G Po Ferrara 7 12/01/04 17:34 Page 1 Cultural Landscapes: the Challenges of Conservation World Heritage 2002 Shared Legacy, Common Responsibility Associated Workshops 11-12 November 2002 Ferrara - Italy Hosted by the Province of Ferrara and the City of Ferrara Organized by the University of Ferrara and UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre in collaboration with ICCROM, ICOMOS and IUCN With the support of the Nordic World Heritage Foundation (NWHF) and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Sciences (OCenW) Ferrara 7 12/01/04 17:34 Page 2 Disclaimer The authors are responsible for the choice and presentation of the facts contained in this publication and for the opinions therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. The designation employed and the presentation of the material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Great Desert Skink Egernia Kintorei? Fires That Could Escape Into the Bush

Australian ThreatenedGreat desert Species skink Egernia kintorei Aboriginal names: Tjakura (Pitjantjatjara/Ngaanyatjarra), Warrarna (Walpiri), Mulyamiji (Manyjilyjarra) Conservation Status What does it look like? Mature adult pairs share burrow systems with their juvenile offspring, and The Great desert skink is a large the young adult skinks leave their birth burrowing skink which weighs up to burrows in their third summer. The Great 350 grams and is about 440 millimetres desert skink are known to move between from the snout to the tip of the tail when burrow systems into vacated burrows of fully grown. other skinks and also those of Mulgaras— The colour of the upper surface of the a rat-sized carnivorous marsupial. skink commonly ranges from light grey to a bright orange-brown while the What does it eat? Great desert skink. Photo by Ada Nano under-parts range from vivid lemon- yellow to creamy grey. The tail is longer Great desert skink feed on large numbers Commonwealth: Vulnerable than the body, and in good seasons the of termites and supplement this dietary mainstay with cockroaches, beetles, (Environment Protection and base of the tail becomes swollen with stored fat reserves. spiders, ants and the occasional small Biodiversity Conservation lizard or flower. Most of their burrow Act 1999) The Great desert skink is one of two systems are located close to termite pans, skinks found in the rangelands listed and the lizards catch termites when they as threatened under the Environment come to the surface to harvest grasses or Northern Territory: Vulnerable Protection and Biodiversity Conservation during dispersal of winged adults. -

Bush Heritage News | Winter 2012 3 Around Your Reserves in 90 Days Your Support Makes a Difference in So Many Ways, Every Day, All Across Australia

In this issue BUSH 3 A year at Carnarvon 4 Around your reserves 6 Her bush memory HERITAGE 7 Easter on Boolcoomatta NEWS 8 From the CEO Winter 2012 www.bushheritage.org.au Your wombat refuge The woodlands and saltlands of your Bon Bon Station Reserve are home to the southern hairy-nosed wombat. These endearing creatures have presented reserve manager Glen Norris with a tricky challenge. Lucy Ashley reports Glen Norris has worked as reserve manager – and he has to work out how to do this “It’s important we reduce rabbit in charge of protecting over 200,000 without harming the wombats, or their hectares of sprawling desert, saltlands, precious burrows. populations, and soon,” says wetlands and woodlands at Bon Bon The ultimate digging machine Glen. “Thanks to lots of help Station Reserve in South Australia for two-and-a-half years. Smaller than their cousin the common from Bush Heritage supporters wombat, southern hairy-nosed wombats Right now, he has a tricky situation on his have soft, fluffy fur (even on their nose), since we bought Bon Bon and hands. long sticky-up ears and narrow snouts. de-stocked it, much of the land Glen has to remove a large population of With squat, strongly built bodies and short highly destructive feral rabbits from legs ending in large paws with strong is now in great condition.” underground warren systems that they’re blade-like claws, they are the ultimate currently sharing with a population of marsupial digging machine. Photograph by Steve Parish protected southern hairy-nosed wombats How you’ve help created a refuge for Bon Bon’s wombats and other native animals • Purchase of the former sheep station in 2008 • Removal of sheep and repair of boundary fences to keep neighbour’s stock out • Control of recent summer bushfires • Soil conservation works to reduce erosion • Ongoing management of invasive weeds like buffel grass • Control programs for rabbits, foxes and feral cats.