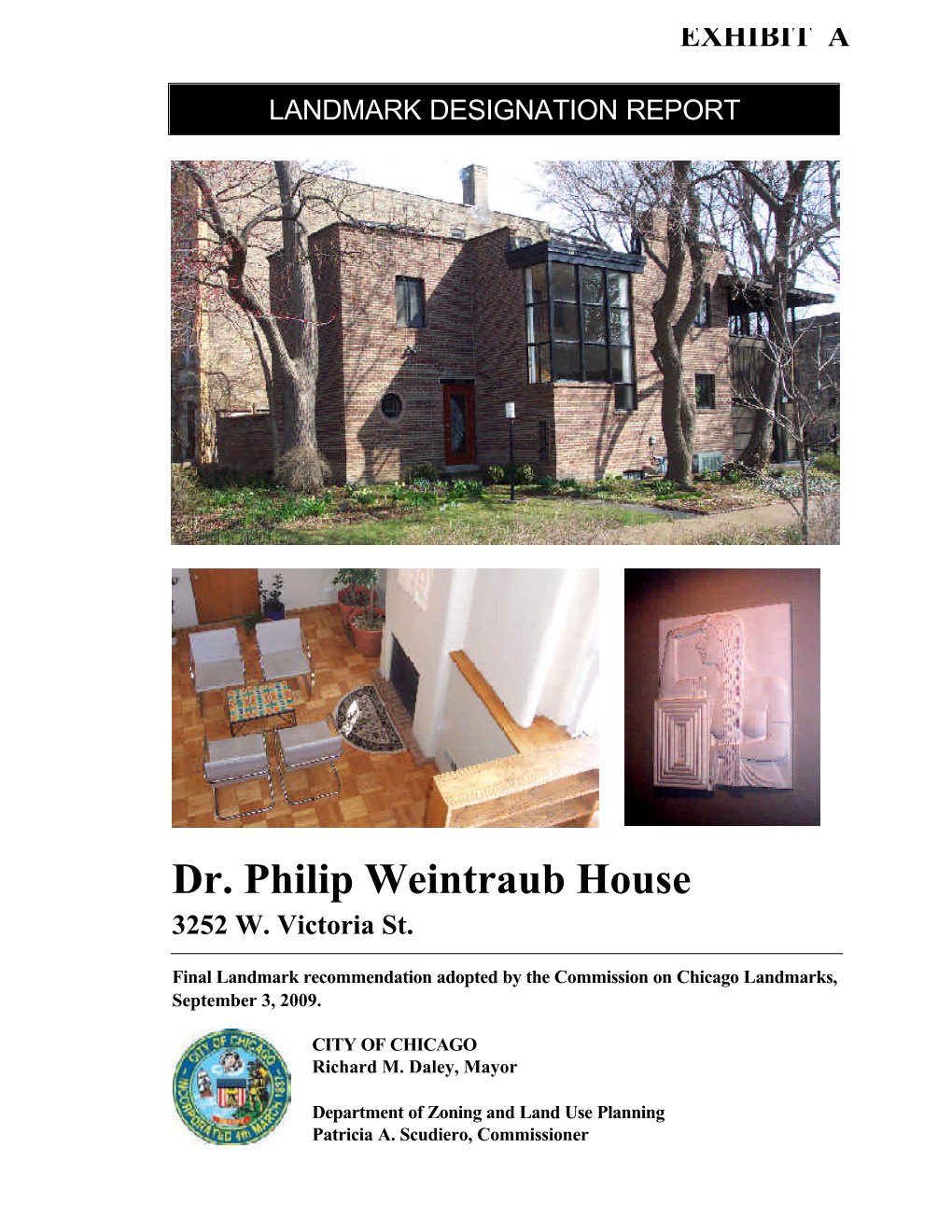

Dr. Philip Weintraub House 3252 W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue in Toronto and Jewelry Deco Pavilion

F A L L 2 0 1 3 Major Art Deco Retrospective Opens in Paris at the Palais de Chaillot… page 11 The Carlu Gatsby’s Fashions Denver 1926 Pittsburgh IN THIS ISSUE in Toronto and Jewelry Deco Pavilion IN THIS ISSUE FALL 2013 FEATURE ARTICLES “Degenerate” Ceramics Revisited By Rolf Achilles . 7 Outside the Museum Doors By Linda Levendusky . 10. Prepare to be Dazzled: Major Art Deco Retrospective Opens in Paris . 11. Art Moderne in Toronto: The Carlu on the Tenth Anniversary of Its Restoration By Scott Weir . .14 Fashions and Jewels of the Jazz Age Sparkle in Gatsby Film By Annette Bochenek . .17 Denver Deco By David Wharton . 20 An Unlikely Art Deco Debut: The Pittsburgh Pavilion at the 1926 Philadelphia Sesquicentennial International Exposition By Dawn R. Reid . 24 A Look Inside… The Art Deco Poster . 27 The Architecture of Barry Byrne: Taking the Prairie School to Europe . 29 REGULAR FEATURES President’s Message . .3 CADS Recap . 4. Deco Preservation . .6 Deco Spotlight . .8 Fall 2013 1 Custom Fine Jewelry and Adaptation of Historic Designs A percentage of all sales will benefit CADS. Mention this ad! Best Friends Elevating Deco Diamonds & Gems Demilune Stacker CADS Member Karla Lewis, GG, AJP, (GIA) Zig Zag Deco By Appointment 29 East Madison, Chicago u [email protected] 312-269-9999 u Mobile: 312-953-1644 bestfriendsdiamonds.com Engagement Rings u Diamond Jewelry u South Sea Cultured Pearl Jewelry and Strands u Custom Designs 2 Chicago Art Deco Society Magazine CADS Board of Directors Joseph Loundy President Amy Keller Vice President PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Susanne Petersson Secretary Mary Miller Treasurer Ruth Dearborn Ann Marie Del Monico Steve Hickson Conrad Miczko Dear CADS Members, Kevin Palmer Since I last wrote to you in April, there have been several important personnel changes at CADS . -

FINAL.Fountain of the Pioneers NR

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Fountain of the Pioneers _______________________________ Other names/site number: Fountain of the Pioneers complex, Iannelli Fountain Name of related multiple property listing: Kalamazoo MRA; reference number 64000327___________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ___________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _in Bronson Park, bounded by Academy, Rose, South and Park Streets_ City or town: _Kalamazoo___ State: _Michigan_ County: _Kalamazoo__ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation -

2001 Wrightiana

7/13/2017 Wrightiana Collection, : Finding Aid - fullfindingaid Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries The Art Institute of Chicago Finding Aid Published: 2001 Wrightiana Collection, c.1897-1997 (bulk 1949-1969) Accession Number: 2001.3 Electronic access to this finding aid was made possible through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. ©Ryerson and Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago. All rights reserved. VIEW ALL DIGITIZED OBJECTS FROM THIS COLLECTION COLLECTION SUMMARY: TITLE: Wrightiana Collection, c.1897-1997 EXTENT: 3.5 linear feet (7 boxes), 4 oversize portfolios and flatfile materials REPOSITORY: Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago 111 S. Michigan Ave., Chica go, IL 60603-6110 (312) 443-7292 phone [email protected] http://www.artic.edu/a ic/libraries/rbarchives/rbarchives.html ABSTRACT: The architecture, furniture, decorative arts, and philosophies of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright are documented through booklets, pamphlets, brochures, letters, transcripts of lectures, published articles, and photographs. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: Printed papers, correspondence, black and white and color photographic prints, architectural reprographic prints, color photomechanical prints, postcards, negatives, printed papers, slides, lantern slides and transparencies, postage stamps, audio media, manuscript and typescript papers, and photocopies. ORIGINATION: Ryerson and Burnham Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago ACQUISITION INFORMATION: This collection is a compilation of material from various sources, including donations from Frank Lloyd Wright, John Lloyd Wright, Bruce Goff, Wilbert Hasbrouck, Carolyn Howlett, William McNeal, Jr. and other unidentified sources. Additional materials were transferred from the D. Coder Taylor and L. Morgan Yost Papers and the Bruce Goff Archive in the Ryerson and Burnham Archives. -

Bronson Park Master Plan

B RONSON PARK MASTER PLAN Cover, back, and chapter title page illustration courtesy of David Jameson, Iannelli Collection. &632732ƫ4%6/ƫ1%78)6ƫ40%2 Prepared for: THE CITY OF KALAMAZOO MICHIGAN Prepared by: 3IJ&3=0)'3;)00&0%03'/ %773'-%8)7-2' Kalamazoo, Michigan Grand Rapids, Michigan and 59-22):%27%6',-8)'87 Madison, Wisconsin Ann Arbor, Michigan September 2015 8,-7ƫ4%+)ƫ-28)28-32%00=ƫ0)*8ƫ&0%2/ 8%&0)ƫ3*ƫ'328)287 ',%48)6-2863(9'8-32 Overview ..................................................................................................................................................................................1.1 Location ..................................................................................................................................................................................1.2 Description of the Project Area ...............................................................................................................................1.2 Project Approach and Objectives ..........................................................................................................................1.2 Cultural Landscape Terminology ...........................................................................................................................1.4 ',%48)60%2(7'%4)',632303+= Overview .................................................................................................................................................................................2.1 Native American Land Use ........................................................................................................................................2.2 -

Bruce Goff Collection Location: Dept

BRUCE GOFF COLLECTION LOCATION: DEPT. OF ARCHITECTURE Architectural Drawings: Projects A—C PROJECT SUMMARY DESCRIPTION OF SHEETS Abbie’s Dress Shop, alterations and additions 2 sheets, Presentation Drawings (built, later demolished) 806 Main Street, Duncan, Oklahoma c. 1955 De Long job number: 55.01 Abraham, Grace and Larry, House (not built) 7 sheets, Presentation Drawings Kansas City, Kansas 4 sheets, Working Drawings 1967 De Long job number: 67.01 Adams, John Quincy (Mr. and Mrs.), House, 3 sheets, Design Drawings number 1 (not built) 6 sheets, Presentation Drawings 310 South Brewer, Vinita, Oklahoma 6 sheets, Working Drawings 1958 De Long job number: 58.01 Delineators: Robert Alan Bowlby and Douglas Harris Adams, John Quincy and Jean, House, number 1 sheet, Design Drawing 3 (built) 2 sheets, Presentation Drawings 310 S. Brewer, Vinita, Oklahoma 2 sheets, Drawings for Publication 1961-62 7 sheets, Working Drawings De Long job number: 61.01 Adams, John Quincy and Jean, House, number 1 sheet, Design Drawing 3 (built) 2 sheets, Presentation Drawings 310 S. Brewer, Vinita, Oklahoma 2 sheets, Drawings for Publication 1961-62 7 sheets, Working Drawings De Long job number: 61.01 Adams, John Quincy, (Mr. and Mrs.), House, 3 sheets, Design Drawings number 2 (not built) 4 sheets, Presentation Drawings Vinita, Oklahoma 5 sheets, Working Drawings 1959 De Long job number: 59.01 Akright, J. R., House alterations and additions 1 sheet, Presentation Drawing (built) 4 sheets, Working Drawings 2412 S. E. Circle Drive, Bartlesville, Oklahoma 1959 De Long job number: 59.02 Allen, Richard, House (not built) 4 sheets, Design Drawings Tulsa, Oklahoma 1954 De Long job number: 54.01 ©Ernest R. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Apprentice Cast His Influence Over Chicago Suburbs

Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice cast his influence over Chicago suburbs Barry Byrne's designs diverged from master but still embraced organic way of building By Blair Kamin October 1, 2013 Architect Barry Byrne gave the interior of St. Thomas an open, column-free space. (Jose M. Osorio, Chicago Tribune) Chicago loves to call itself the cradle of modern architecture, but what exactly is modern architecture? The steel and glass skyscrapers of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe? The Prairie School houses of Frank Lloyd Wright? Maybe those are the wrong questions. To some, modernism isn't — or, rather, shouldn't be — a style. A building's inner workings, especially its floor plan and the activities it organizes, should generate its outer shell. Form ought to follow function, not fashion. The late Chicago architect Barry Byrne, an apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright, believed passionately in this organic way of building. "We know too much about surface things, too little about what lies beyond the surface," he once wrote. Byrne, who died in 1967 at 83, was a devout Catholic who pushed his church in new architectural directions. His thrust-altar churches in Chicago, Tulsa, Okla., and Cork, Ireland, anticipated by decades the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council, which sought to break down traditional barriers between priests and parishioners. Byrne's buildings, including private homes, schools and dormitories, also grace the Chicago suburbs of Wilmette, Lisle and Park Ridge. But like many of Wright's apprentices, he's long been obscured by the master's shadow. He gets his due, though, in a fine new biography, "The Architecture of Barry Byrne: Taking the Prairie School to Europe." The book, by Vincent Michael, executive director of the Global Heritage Fund in Palo Alto, Calif., and a faculty member at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, skillfully reveals how Byrne carved a path separate from Wright's and sheds fresh light on his interactions with Europe's architectural avant-garde. -

John Francis Kenna Apartments 223> East 69Th Street Chicago Cook

John Francis Kenna Apartments HAES No. ILL-109^ 223> East 69th Street Chicago Cook County Illinois HAES ILL, 16-CHIG, 81*- • .-•.; PHOTOGRAPHS->. ^ WEITTEN HISTORICAL Aro;i)SBCRIHTI^ DATA # ■;. ■':.. •;-; Historic-;Airierican^Bmidings".:Suryej;-; Office ':0?/ Archeology and Hi'Stdric". PreServat-ion "''-" ■'• "^"':''/."/:::;IatIdhai Pa#&; B^rmee--;-" '.;'■.'•':.:■-•■_%'••'--■■ .;.: -\:7 :;'■--■; ;:\\D.epar'imeiitko-f;the.Int'erioi*.■.- ■ -.-/,:"':-,.'.:V HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. ILL-1091* HABS JOHN FRANCIS KEHNA APARTMENTS ILL, l6-CHIG,8U- Location: 22lU East 69th Street, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois. Present Owner: Harold. Pates and wife. Present pccupantg_: The premises are rented, Present Use: Apartment House. Statement of A "building of marked simplicity, the Kenna Apart--- Significance: ment Building "by Francis Barry Byrne shows a continuation of the Prairie School idea in a highly individualistic manner which shows assimilation of the contemporary work of the Californian, Irving Gill. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History: 1. Original and subsequent owners: Legal description: in lands, part of Block k of the South Shore Subdivision • number 5 of the eastern half of the southeastern quarter of Section 2k, Township 38, Range ik. Chain of title: from the Chicago Title and Trust Company, tract hook Uoi-3. John Francis Kenna originally "bought the land on which the apartment "building was to stand in two large parcels, falling on both sides of the center line of Block k. The first part to be purchased was the southern 200 feet of the east half of the block, which John F. Kenna purchased from James Stewert, September 26, 1913 (Document 5289^26). The second parcel consisting of the southernmost 80 feet of the west half of the block, Kenna purchased from Frank A. -

Historic Preservation & Cultural Resources Multi

Tulsa Historic Preservation & Cultural Resources Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan - 2011 ENGINEERING SERVICES September 8, 2011 Mr. Bill Penka, State Hazard Mitigation Officer Oklahoma Department of Civil Emergency Management P.O. Box 53365 Oklahoma City, OK 73152 RE: City of Tulsa Historic Preservation and Cultural Resources Annex We are pleased to submit this City of Tulsa Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan- 2009 Update, Historic Preservation and Cultural Resources Annex as fulfillment of the requirements of the Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Grant (PDMC-PJ-06- OK-2007-004). This Historic Preservation and Cultural Resources Annex Pilot Study was prepared in accordance with State and Federal guidance, addresses Districts and Properties Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, Art Deco Buildings, and Cultural Resources, and their vulnerability to Natural and Man- made Hazards. We look forward to implementing this plan to enhance protection of the lives and property of our citizens from natural hazards and hazard materials incidents. If we can answer any questions or be of further assistance, please do not hesitate to contact me at 918-596-9475. CITY OF TULSA, DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS Sincerely, Bill Robison, P.E., CFM Senior Special Projects Engineer Stormwater Planning 2317 S. Jackson Ave., Room S-310 Tulsa, OK 74107 Office 918-596-9475 www.cityoftulsa.org Table of Contents Acknowledgements..................................................................................................... xii Summary.................................................................................................................... -

ADC Study Collection, 1855-2013 0000210

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8bz66m3 No online items Finding Aid for the ADC Study collection, 1855-2013 0000210 Finding aid prepared by Alexandra Adler, Chris Marino and Jocelyne Lopez The processing of this collection was made possible through generous funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, administered through the Council on Library and Information Resources “Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives” Project. Architecture and Design Collection, Art, Design & Architecture Museum Arts Building Room 1434 University of California Santa Barbara, California, 93106-7130 805-893-2724 [email protected] 2012 Finding Aid for the ADC Study 0000210 1 collection, 1855-2013 0000210 Title: ADC Study collection Identifier/Call Number: 0000210 Contributing Institution: Architecture and Design Collection, Art, Design & Architecture Museum Language of Material: English Physical Description: 4.5 Linear feet(9 half record storage boxes) Date (inclusive): 1855-2013 Location note: Boxes 1-9/ADC - regular Access Open for use by qualified researchers. Preferred Citation note ADC Study collection, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara. Biographical/Historical note Collection was formed by the repository from small separate acquisitions, and is added to periodically. Scope and Contents note The ADC Study collection spans 4.5 linear feet and dates from circa 1855 to the present. The collection, compiled by the repository from assorted acquisitions, contains photographs, negatives, ephemera including posters, articles and clippings and a few documents, all organized alphabetically by architect or topic and arranged in three series: Articles and Clippings, Photographic Materials, and Printed Ephemera. Note that the respository has additional material in other collections about architects and topics in this collection. -

Alfonso Ian Nelli

Published by the Hyde Park Historical Society Grace Green, a freshman at St. Ignatim High School, submitted her project on Alfonso Iannelli to the Chicago Metro History Fair. It was judged the best entry in the Fair that was related to Hyde Park. At the History Fair final awards ceremony, Grace was awarded $100 by Priya Shintpi on behalfofthe Hyde Park Historical Society. The project which Grace submitted was a large standing exhibit with many pictures and nmch accompanying text. The following essay was put togethe1' from the textllal part 0/ her display by Jay Mulberry. ALFONSO IAN NELLI Board member Priya Shimpi and prize winner Grace Green By Grace Green First Place Winner in the 2004 Hyde Park Historical 1898, an up-and-coming industrial city overwhelmed Society Neighborhood History Contest in gray smoke. Iannelli went to public school but when his father's business collapsed he was forced at As a native of Italy, Iannelli is a classic example of age 13 to leave school. His father arranged an the American Dream. As early as ten years old he had apprenticeship at a jeweler's shop where Iannelli immense desire to work in the arts and America learned to engrave. A special scholarship to the seemed to be the key to ultimate success. From New Newark Technical School made it possible for him to York to Los Angeles and eventually Chicago, his final study there in the evenings and work in the shop resting place, he made an indelible mark across the during the day. In 1906, he won a scholarship for the American landscape. -

Unbuilt Chicago: Right up My Alley by Barbara Stodola the Exhibition Title Is a Dead Give-Away

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 20, Number 16 Thursday, April 29, 2004 Unbuilt Chicago: Right Up My Alley by Barbara Stodola The exhibition title is a dead give-away. “Unbuilt Chicago” is the stuff of dreams and fantasies, architects’ lofty visions of what might have been. More optimistic than “Lost Chicago.” More entertaining than previews of functional structures that actually go up. This exhib- it, currently at the Art Institute of Chicago, allows us to peek at the drawing boards where the architect’s creativity flourishes, unimpeded by the client’s pocketbook. Little wonder that the exhibition should contain drawings for war memorials and yacht clubs, Magic Mountain and Ziegfield Follies, soaring skyscrapers and buildings that slowly inch their way up. This is the world of dreamland. As long ago as 1892, an architect named Peter Weber proposed a 400-foot-tall structure for the Chicago World’s Fair that resembled the Leaning Tower of Pisa, except that it didn’t lean. In its famous spiral there would have been an electric railway, winding around and upward and taking visitors to the top of the tower. Instead of this attraction, the Columbian Exposition introduced a giant ferris wheel to Chicagoans -- another way of getting to the top. Daniel Burnham, grand-daddy of Chicago architects and author of the 1909 Plan of Chicago, has two grandiose schemes in this exhib- it: a great, multi-storied, hulking Civic Center with an elliptical dome, and a massive pleasure palace for the Chicago Yacht Club, with Palladian windows overlooking the harbor. -

The Prairie School Review Index

THE PRAIRIE SCHOOL REVIEW INDEX Call 312-326-1480 or email [email protected] with your inquiries and to place your order. Quantities of original issues are limited, but high-quality copies can also be provided. Cost $10. VOLUME I, NUMBER 1 (First Quarter, 1964) - J. William Rudd – George W. Maher: Architect of the Prairie School - G. W. Maher - Originality in American Architecture - Measured Drawing: Front elevation of the Administration Building for the J. R. Watkins Medical Co. of Winona, Minn., George W. Maher, architect - The Work of G. W. Maher, a partial list of executed buildings VOLUME I, NUMBER 2 (Second Quarter, 1964) - W. R. Hasbrouck – The Architectural Firm of Guenzel and Drummond - W. E. Drummond – On Things of Common Concern - Carolyn Hedlund – Life in a Prairie School House - Measured Drawing: Fireplace Detail of William E. Drummond Residence - The Work of Guenzel and Drummond, a partial list of executed buildings VOLUME I, NUMBER 3 (Third Quarter, 1964) - Frank Lloyd Wright’s First Independent Commission - A Portfolio of the Winslow House - Measured Drawing: West Elevation of the Winslow House - Leonard K. Eaton – William Herman Winslow and the Winslow House - Richard D. Johnson – From Contractor’s Scrap to Museum Display VOLUME I, NUMBER 4 (Fourth Quarter, 1964) - Donald Kalec – The Prairie School Furniture - Measured Drawing: Robie House Dining Room buffet - Portfolio of Prairie School Furniture - Donald L. Hoffmann – Elmslie’s Topeka Legacy VOLUME II, NUMBER 1 (First Quarter, 1965) - David Gebhard – Purcell and