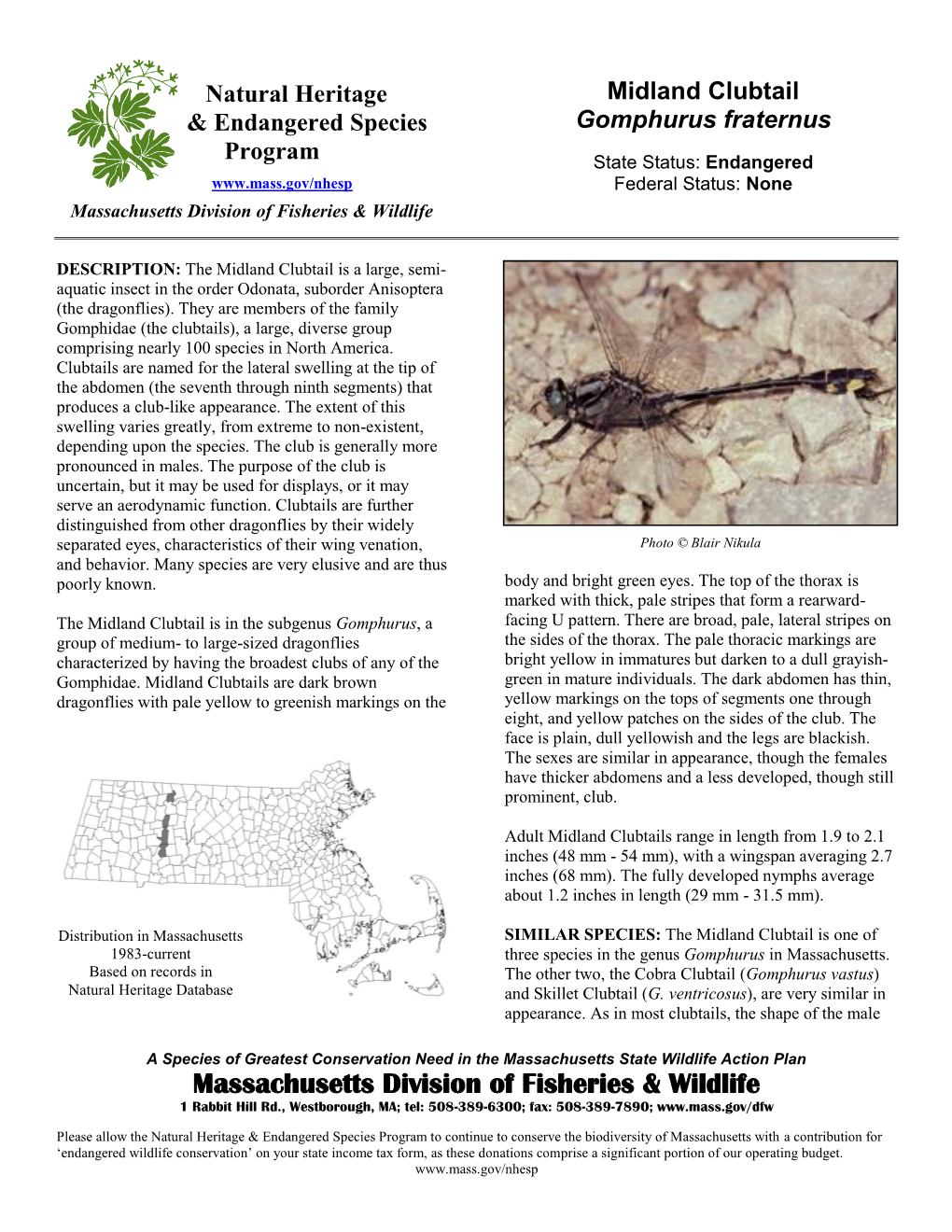

Midland Clubtail, Gomphurus Fraternus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olive Clubtail (Stylurus Olivaceus) in Canada, Prepared Under Contract with Environment Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olive Clubtail Stylurus olivaceus in Canada ENDANGERED 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olive Clubtail Stylurus olivaceus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 58 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Robert A. Cannings, Sydney G. Cannings, Leah R. Ramsay and Richard J. Cannings for writing the status report on Olive Clubtail (Stylurus olivaceus) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Paul Catling, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Arthropods Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le gomphe olive (Stylurus olivaceus) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Olive Clubtail — Photo by Jim Johnson. Permission granted for reproduction. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011. Catalogue No. CW69-14/637-2011E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-18707-5 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2011 Common name Olive Clubtail Scientific name Stylurus olivaceus Status Endangered Reason for designation This highly rare, stream-dwelling dragonfly with striking blue eyes is known from only 5 locations within three separate regions of British Columbia. -

Skillet Clubtail

Species Status Assessment Class: Insecta Family: Gomphidae Scientific Name: Gomphus ventricosus Common Name: Skillet clubtail Species synopsis: The distribution center of G. ventricosus lies along the Lake Erie shoreline in northeast Ohio in the southern Great Lakes forest ecoregion, extending northwest to northern Minnesota, east to Nova Scotia, and south to central Tennessee (Donnelly 2004). G. ventricosus is rare and spottily distributed throughout its range, particularly in the east (Walker 1958). Although extensive searches during the New York State Dragonfly and Damselfly Survey (NYSDDS) failed to detect the species in eastern New York, recent records suggest that it should occur there. These records include occurrences from the Connecticut River in Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well as smaller rivers near the NY border, such as the Housatonic (Massachusetts NHESP 2003). G. ventricosus was formerly known in New York State from two pre-1926 records— one from Pine Island, probably the upper Wallkill River (where the species still occurs in New Jersey), and another from Old Forge (likely on the Moose River). A 2009 survey of the Moose River was not successful in locating any individuals. However, a new population was documented in New York along the Raquette River between Potsdam and Massena on the northeast Lake Ontario/St. Lawrence Plain in both 1997 and 1998 (White et al. 2010). Throughout its range, G. ventricosus prefers small to large turbid rivers with partial mud bottoms, but good water quality. An older locale in Pine Island of Orange County, presumably along the upper Wallkill River, was a slow moving creek with a muddy/muck bottom and stained/turbid water. -

NYSDEC SWAP High Priority SGCN Dragonflies Damselflies

Common Name: Tiger spiketail SGCN – High Priority Scientific Name: Cordulegaster erronea Taxon: Dragonflies and Damselflies Federal Status: Not Listed Natural Heritage Program Rank: New York Status: Not Listed Global: G4 New York: S1 Tracked: Yes Synopsis: The distributional center of the tiger spiketail (Cordulegaster erronea) is in northeastern Kentucky in the mixed mesophytic forest ecoregion, and extends southward to Louisiana and northward to western Michigan and northern New York. New York forms the northeastern range extent and an older, pre-1926 record from Keene Valley in Essex County is the northernmost known record for this species. Southeastern New York is the stronghold for this species within the lower Hudson River watershed in Orange, Rockland, Putnam and Westchester counties and is contiguous with New Jersey populations (Barlow 1995, Bangma and Barlow 2010). These populations were not discovered until the early 1990s and some have remained extant, while additional sites were added during the New York State Dragonfly and Damselfly Survey (NYSDDS). A second occupied area in the Finger Lakes region of central New York has been known since the 1920s and was rediscovered at Excelsior Glen in Schuyler County in the late 1990s. During the NYDDS, a second Schuyler County record was reported in 2005 as well as one along a small tributary stream of Otisco Lake in southwestern Onondaga County in 2008 (White et al. 2010). The habitat in the Finger Lakes varies slightly from that in southeastern New York and lies more in accordance with habitat in Michigan (O’Brien 1998) and Ohio (Glotzhober and Riggs 1996, Glotzhober 2006)—exposed, silty streams flowing from deep wooded ravines into large lakes (White et al. -

A Checklist of North American Odonata

A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009 Edition (updated 14 April 2009) A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution 2009 Edition (updated 14 April 2009) Dennis R. Paulson1 and Sidney W. Dunkle2 Originally published as Occasional Paper No. 56, Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, June 1999; completely revised March 2009. Copyright © 2009 Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009 edition published by Jim Johnson Cover photo: Tramea carolina (Carolina Saddlebags), Cabin Lake, Aiken Co., South Carolina, 13 May 2008, Dennis Paulson. 1 1724 NE 98 Street, Seattle, WA 98115 2 8030 Lakeside Parkway, Apt. 8208, Tucson, AZ 85730 ABSTRACT The checklist includes all 457 species of North American Odonata considered valid at this time. For each species the original citation, English name, type locality, etymology of both scientific and English names, and approxi- mate distribution are given. Literature citations for original descriptions of all species are given in the appended list of references. INTRODUCTION Before the first edition of this checklist there was no re- Table 1. The families of North American Odonata, cent checklist of North American Odonata. Muttkows- with number of species. ki (1910) and Needham and Heywood (1929) are long out of date. The Zygoptera and Anisoptera were cov- Family Genera Species ered by Westfall and May (2006) and Needham, West- fall, and May (2000), respectively, but some changes Calopterygidae 2 8 in nomenclature have been made subsequently. Davies Lestidae 2 19 and Tobin (1984, 1985) listed the world odonate fauna Coenagrionidae 15 103 but did not include type localities or details of distri- Platystictidae 1 1 bution. -

Ocn957287850.Pdf (224.8Kb)

Natural Heritage Cobra Clubtail & Endangered Species Gomphus vastus Program State Status: Special Concern www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION: The Cobra Clubtail is a large, semi- aquatic insect in the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies). They are members of the family Gomphidae (the clubtails), a large, diverse group comprising nearly 100 species in North America. Clubtails are named for the lateral swelling at the tip of the abdomen (the seventh through ninth segments) that produces a club-like appearance. The extent of this swelling varies greatly, from extreme to non-existent, depending upon the species. The club is generally more pronounced in males than females. The purpose of the club is uncertain, but it may be used for displays or it may provide some aerodynamic benefits to the males. Clubtails are further distinguished from other dragonflies by their widely separated eyes, wing venation Photo © Blair Nikula characteristics, and behavior. Many species are very elusive and thus poorly known. thick, pale stripes that form a rearward-facing U pattern. The Cobra Clubtail is in the subgenus Gomphurus, a There are broad, pale, lateral stripes on the sides of the group characterized by having the broadest clubs of any thorax. The pale thoracic markings are bright yellow in of the Gomphidae. Cobra Clubtails are dark brown the young adults, but become a dull, grayish-green as the dragonflies with pale yellow to greenish markings on the insect matures. The dark abdomen has thin, yellow body and bright green eyes. The top of the thorax is markings on the tops of segments one through seven and bright yellow patches on the sides of the club. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2018

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2018 Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus) photo by Clifton Avery Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2018 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

A Checklist of North American Odonata, 2021 1 Each Species Entry in the Checklist Is a Paragraph In- Table 2

A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2021 Edition (updated 12 February 2021) A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution 2021 Edition (updated 12 February 2021) Dennis R. Paulson1 and Sidney W. Dunkle2 Originally published as Occasional Paper No. 56, Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, June 1999; completely revised March 2009; updated February 2011, February 2012, October 2016, November 2018, and February 2021. Copyright © 2021 Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009, 2011, 2012, 2016, 2018, and 2021 editions published by Jim Johnson Cover photo: Male Calopteryx aequabilis, River Jewelwing, from Crab Creek, Grant County, Washington, 27 May 2020. Photo by Netta Smith. 1 1724 NE 98th Street, Seattle, WA 98115 2 8030 Lakeside Parkway, Apt. 8208, Tucson, AZ 85730 ABSTRACT The checklist includes all 471 species of North American Odonata (Canada and the continental United States) considered valid at this time. For each species the original citation, English name, type locality, etymology of both scientific and English names, and approximate distribution are given. Literature citations for original descriptions of all species are given in the appended list of references. INTRODUCTION We publish this as the most comprehensive checklist Table 1. The families of North American Odonata, of all of the North American Odonata. Muttkowski with number of species. (1910) and Needham and Heywood (1929) are long out of date. The Anisoptera and Zygoptera were cov- Family Genera Species ered by Needham, Westfall, and May (2014) and West- fall and May (2006), respectively. -

A Checklist of Oklahoma Odonata

Libellula comanche Calvert, 1907 - Comanche Skimmer Useful regional references: Libellula composita (Hagen, 1873) - Bleached Skimmer A Checklist of Libellula croceipennis Selys, 1868 - Neon Skimmer —Dragonflies and damselflies of the West by Dennis Paulson (2009) Libellula cyanea Fabricius, 1775 - Spangled Skimmer and Dragonflies and damselflies of the East by Dennis Paulson (2011) Oklahoma Odonata Libellula flavida Rambur, 1842 - Yellow-sided Skimmer Princeton University Press. Libellula incesta Hagen, 1861 - Slaty Skimmer —Damselflies of Texas: A Field Guide by John C. Abbott (2011) and (Dragonflies and Damselflies) Libellula luctuosa Burmeister, 1839 - Widow Skimmer Dragonflies of Texas: A Field Guide by John C. Abbott (2015) University of Texas Press. Libellula nodisticta Hagen, 1861 - Hoary Skimmer Libellula pulchella Drury, 1773 - Twelve-spotted Skimmer —Oklahoma Odonata Project: https://biosurvey.ou.edu/smith/Oklahoma_Odonata.html Libellula saturata Uhler, 1857 - Flame Skimmer Compiled by Brenda D. Smith — Smith BD, Patten MA (2020) Dragonflies at a Biogeographical Libellula semifasciata Burmeister, 1839 - Painted Skimmer Crossroads: The Odonata of Oklahoma and Complexities Beyond its & Michael A. Patten Libellula vibrans Fabricius, 1793 - Great Blue Skimmer Borders. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, USA. Macrodiplax balteata (Hagen, 1861) - Marl Pennant Miathyria marcella (Selys, 1856) - Hyacinth Glider Oklahoma Biological Survey, Micrathyria hagenii Kirby, 1890 - Thornbush Dasher Oklahoma -

Dragonflies of A( Nisoptera) Arkansas George L

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 31 Article 17 1977 Dragonflies of A( nisoptera) Arkansas George L. Harp Arkansas State University John D. Rickett University of Arkansas at Little Rock Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Harp, George L. and Rickett, John D. (1977) "Dragonflies of (Anisoptera) Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 31 , Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol31/iss1/17 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 31 [1977], Art. 17 The Dragonflies (Anisoptera) of Arkansas GEORGE L.HARP Division of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University State University, Arkansas 72467 JOHND. RICKETT Department of Biology, University of Arkansas at LittleRock LittleRock, Arkansas 72204 ABSTRACT Previous publications have recorded 69 species of dragonflies for Arkansas. Three of these are deleted, but state records for 21 new species are reported herein, bringing the list to 87 species. -

Geographic Variation in a Restricted-Range Endemic Dragonfly Gomphurus Ozarkensis (Odonata: Gomphidae), with Description of a New Subspecies

J. Insect Biodiversity 013 (2): 015–026 ISSN 2538-1318 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/jib J. Insect Biodiversity Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2147-7612 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.12976/jib/2019.13.2.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1EDFA307-DBE4-4C91-AC62-02845C7AA214 Geographic variation in a restricted-range endemic dragonfly Gomphurus ozarkensis (Odonata: Gomphidae), with description of a new subspecies MICHAEL A. PATTEN1, ALEXANDRA A. BARNARD1,2 & BRENDA D. SMITH1 1Oklahoma Biological Survey, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma 73019, USA 2Current affiliation: Math and Sciences Division, National Park College, Hot Springs, Arkansas 71913, USA *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The geographic distribution of Gomphurus ozarkensis (Westfall, 1975), a species described to science only four decades ago, is confined to a four-state area in the central United States: southeastern Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, western and northern Arkansas, and southern Missouri. Its small range has led some to classify it a species of conservation concern. We examined geographic variation in the species, which despite its small range exists in three distinct subpopulations: one in the Ouachita Mountains of western Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma; one on the Ozark Plateau of northeastern Oklahoma, south- eastern-most Kansas, southern Missouri, and northern Arkansas; and one in the Osage/Flint hills of southeastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma. Clinal variation is evident in the extent of yellow on the terminal abdominal segments and the extent to which certain thoracic stripes are fused. A population in a separate watershed basin in the southern Osage Hills of Okla- homa is taxonomically distinct, with some phenotypic characters tending toward G. -

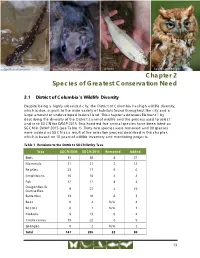

Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Spotted salamander Southern flying squirrel Alewife Eastern screech owl Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1 District of Columbia’s Wildlife Diversity Despite being a highly urbanized city, the District of Columbia has high wildlife diversity, which is due, in part, to the wide variety of habitats found throughout the city and a large amount of undeveloped federal land. This chapter addresses Element 1 by describing the diversity of the District’s animal wildlife and the process used to select and rank SGCN for SWAP 2015. Two hundred five animal species have been listed as SGCN in SWAP 2015 (see Table 1). Thirty-two species were removed and 90 species were added as SGCN as a result of the selection process described in this chapter, which is based on 10 years of wildlife inventory and monitoring projects. Table 1 Revisions to the District’s SGCN list by Taxa Taxa SGCN 2005 SGCN 2015 Removed Added Birds 35 58 4 27 Mammals 11 21 2 12 Reptiles 23 17 6 0 Amphibians 16 18 2 4 Fish 12 12 4 4 Dragonflies & 9 27 2 19 Damselflies Butterflies 13 10 6 3 Bees 0 4 N/A 4 Beetles 0 1 N/A 1 Mollusks 9 13 0 4 Crustaceans 19 22 6 9 Sponges 0 2 N/A 2 Total 147 205 32 90 13 Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1.1 Terrestrial Wildlife Diversity The District has a substantial number of terrestrial animal species, and diverse natural communities provide an extensive variety of habitat settings for wildlife. -

Washburn County

Washburn County Note: Observations of species shown in bold are 50 or more years old, and we are especially interested in updating these records. Checklist last updated: March 19, 2021 Lestidae – Spreadwing Family Lestes disjunctus - Northern Spreadwing (2011) Lestes eurinus - Amber-winged Spreadwing (2011) Lestes rectangularis - Slender Spreadwing (2020) Lestes unguiculatus - Lyre-tipped Spreadwing (2002) Lestes vigilax - Swamp Spreadwing (2020) Calopterygidae – Broad-winged Damsel Family Calopteryx aequabilis - River Jewelwing (2010) Calopteryx maculata - Ebony Jewelwing (2010) Coenagrionidae – Pond Damsel Family Enallagma annexum - Northern Bluet (2011) Enallagma boreale - Boreal Bluet (1989) Enallagma carunculatum - Tule Bluet (2005) Enallagma ebrium - Marsh Bluet (2011) Enallagma exsulans - Stream Bluet (2005) Enallagma geminatum - Skimming Bluet (2016) Enallagma hageni - Hagen's Bluet (2011) Enallagma vesperum - Vesper Bluet (2003) Ischnura verticalis - Eastern Forktail (2020) Nehalennia irene - Sedge Sprite (2011) Aeshnidae – Darner Family Aeshna eremita - Lake Darner (2003) Aeshna tuberculifera - Black-tipped Darner (2003) Aeshna umbrosa - Shadow Darner (2012) Anax junius - Common Green Darner (2020) Basiaeschna janata - Springtime Darner (2010) Boyeria vinosa - Fawn Darner (2012) Nasiaeschna pentacantha - Cyrano Darner (2010) Gomphidae – Clubtail Family Arigomphus furcifer - Lilypad Clubtail (2017) Dromogomphus spinosus - Black-shouldered Spinyleg (2010) Gomphurus fraternus - Midland Clubtail (2009) Gomphurus lineatifrons - Splendid