A Moratorium on Intersex Surgeries?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Webbed Penis

Kathmandu University Medical Journal (2010), Vol. 8, No. 1, Issue 29, 95-96 Case Note Webbed penis: A rare case Agrawal R1, Chaurasia D2, Jain M3 1Resident in Surgery, 2Associate Professor, Department of Urology, 3Assistant Professor, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, MLN Medical College, Allahabad (India) Abstract Webbed penis belongs to a rare and little-known defect of the external genitalia. The term denotes the penis of normal size for age hidden in the adjacent scrotal and pubic tissues. Though rare, it can be treated easily by surgery. A case of webbed penis is presented with brief review of literature. Key words: penis, webbed ebbed penis is a rare anomaly of structure of Wpenis. Though a congenital anomaly, usually the patient presents in late childhood or adolescence. Skin of penis forms the shape of a web, covering whole or part of penis circumferentially; with or without glans, burying the penile tissue inside. The length of shaft is normal with normal stretched length. Phimosis may be present. The penis appears small without any diffi culty in voiding function. Fig 1: Penis showing web Fig 2: Markings for double of skin on anterior Z-plasty on penis Case report aspect Our patient, a 17 year old male, presented to us with congenital webbed penis. On examination, skin webs Discussion were present on both lateral sides from prepuce to lateral Webbed penis is a developmental malformation with aspect of penis.[Fig. 1] On ventral aspect, the skin web less than 60 cases reported in literature. The term was present from prepuce to inferior margin of median denotes the penis of normal size for age hidden in the raphe of scrotum. -

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S. Tekgül (Chair), H.S. Dogan, E. Erdem (Guidelines Associate), P. Hoebeke, R. Ko˘cvara, J.M. Nijman (Vice-chair), C. Radmayr, M.S. Silay (Guidelines Associate), R. Stein, S. Undre (Guidelines Associate) European Society for Paediatric Urology © European Association of Urology 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Aim 7 1.2 Publication history 7 2. METHODS 8 3. THE GUIDELINE 8 3A PHIMOSIS 8 3A.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 8 3A.2 Classification systems 8 3A.3 Diagnostic evaluation 8 3A.4 Disease management 8 3A.5 Follow-up 9 3A.6 Conclusions and recommendations on phimosis 9 3B CRYPTORCHIDISM 9 3B.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 9 3B.2 Classification systems 9 3B.3 Diagnostic evaluation 10 3B.4 Disease management 10 3B.4.1 Medical therapy 10 3B.4.2 Surgery 10 3B.5 Follow-up 11 3B.6 Recommendations for cryptorchidism 11 3C HYDROCELE 12 3C.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 12 3C.2 Diagnostic evaluation 12 3C.3 Disease management 12 3C.4 Recommendations for the management of hydrocele 12 3D ACUTE SCROTUM IN CHILDREN 13 3D.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 13 3D.2 Diagnostic evaluation 13 3D.3 Disease management 14 3D.3.1 Epididymitis 14 3D.3.2 Testicular torsion 14 3D.3.3 Surgical treatment 14 3D.4 Follow-up 14 3D.4.1 Fertility 14 3D.4.2 Subfertility 14 3D.4.3 Androgen levels 15 3D.4.4 Testicular cancer 15 3D.5 Recommendations for the treatment of acute scrotum in children 15 3E HYPOSPADIAS 15 3E.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology -

![Springer MRW: [AU:0, IDX:0]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3905/springer-mrw-au-0-idx-0-323905.webp)

Springer MRW: [AU:0, IDX:0]

Pre-Testicular, Testicular, and Post- Testicular Causes of Male Infertility Fotios Dimitriadis, George Adonakis, Apostolos Kaponis, Charalampos Mamoulakis, Atsushi Takenaka, and Nikolaos Sofikitis Abstract Infertility is both a private and a social health problem that can be observed in 12–15% of all sexually active couples. The male factor can be diagnosed in 50% of these cases either alone or in combination with a female component. The causes of male infertility can be identified as factors acting at pre-testicular, testicular or post-testicular level. However, despite advancements, predominantly in the genetics of fertility, etiological factors of male infertility cannot be identi- fied in approximately 50% of the cases, classified as idiopathic infertility. On the other hand, the majority of the causes leading to male infertility can be treated or prevented. Thus a full understanding of these conditions is crucial in order to allow the clinical andrologist not simply to retrieve sperm for assisted reproduc- tive techniques purposes, but also to optimize the male’s fertility potential in order to offer the couple the possibility of a spontaneous conceivement. This chapter offers the clinical andrologist a wide overview of pre-testicular, testicular, and post-testicular causes of male infertility. F. Dimitriadis Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece e-mail: [email protected] G. Adonakis • A. Kaponis Department of Ob/Gyn, School of Medicine, Patras University, Patras, Greece C. Mamoulakis Department of Urology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Crete, Greece A. Takenaka Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Tottori University, Yonago, Japan N. Sofikitis (*) Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Ioannina University, Ioannina, Greece e-mail: [email protected] # Springer International Publishing AG 2017 1 M. -

Evaluation of Additional Anomalies in Concomitance of Hypospadias And

Türkiye Çocuk Hastalıkları Dergisi 222 Özgün Araştırma Original Article Turkish Journal of Pediatric Disease Evaluation of Additional Anomalies in Concomitance of Hypospadias and Undescended Testes Hipospadias ve İnmemiş Testis Birlikteliğinde Ek Anomali Sıklığının Değerlendirilmesi Ufuk ATES, Gülnur GÖLLÜ, Nil YAŞAM TAŞTEKİN, Anar QURBANOV, Günay EKBERLİ, Meltem BİNGÖL KOLOĞLU, Emin AYDIN YAĞMURLU, Tanju AKTUĞ, Hüseyin DİNDAR, Ahmet Murat ÇAKMAK Ankara University Medical School, Pediatric Surgery Department, Pediatric Urology Division, Ankara, Turkey ABSTRACT Objective: Hypospadias is a common genitourinary system (GUS) anomaly in boys occurring in 1 of 200 to 300 live births. Undescended testes is frequently detected among accompanying anomalies in cases with hypospadias. Especially in proximal hypospadias and bilateral cases, this association may indicate sexual differentiation disorders. The aim of the study was to evaluate the togetherness of additional anomalies in hypospadiac children with undescended testes. Material and Methods: Between 2007 and 2016, data of 392 children who underwent surgery for hypospadias were evaluated retrospectively. Urethral meatus was present at scrotal and penoscrotal in 65 cases (16.6%) and glanular, coronal, subcoronal and midpenile in 327 cases (83.4%). The cases were divided into two groups as those with both testes in the scrotum and those with undescended testes, and the anomalies were recorded. Results: The mean age of the children with proximal hypospadias was 21 months (6-240 months). Of the children with proximal hypospadias, 26 (40%) had undescended testes and 39 (60%) had testes in the scrotum. Undescended testes were detected bilaterally in 17 patients (65.4%) and unilaterally in nine patients (34.6%) in the undescended testes group. -

Penile Anomalies in Adolescence

Review Special Issue: Penile Anomalies in Children TheScientificWorldJOURNAL (2011) 11, 614–623 TSW Urology ISSN 1537-744X; DOI 10.1100/tsw.2011.38 Penile Anomalies in Adolescence Dan Wood* and Christopher Woodhouse Adolescent Urology Department, University College London Hospitals E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received August 13, 2010; Revised January 9, 2011; Accepted January 11, 2011; Published March 7, 2011 This article considers the impact and outcomes of both treatment and underlying condition of penile anomalies in adolescent males. Major congenital anomalies (such as exstrophy/epispadias) are discussed, including the psychological outcomes, common problems (such as corporal asymmetry, chordee, and scarring) in this group, and surgical assessment for potential surgical candidates. The emergence of new surgical techniques continues to improve outcomes and potentially raises patient expectations. The importance of balanced discussion in conditions such as micropenis, including multidisciplinary support for patients, is important in order to achieve appropriate treatment decisions. Topical treatments may be of value, but in extreme cases, phalloplasty is a valuable option for patients to consider. In buried penis, the importance of careful assessment and, for the majority, a delay in surgery until puberty has completed is emphasised. In hypospadias patients, the variety of surgical procedures has complicated assessment of outcomes. It appears that true surgical success may be difficult to measure as many men who have had earlier operations are not reassessed in either puberty or adult life. There is also a brief discussion of acquired penile anomalies, including causation and treatment of lymphoedema, penile fracture/trauma, and priapism. -

Butler-Doing-Justice.Pdf

GLQ 7.4-05 Butler 10/16/01 5:15 PM Page 621 DOING JUSTICE TO SOMEONE Sex Reassignment and Allegories of Transsexuality Judith Butler I would like to take my point of departure from a question of power, the power of regulation, a power that determines, more or less, what we are, what we can be. I am not speaking of power only in a juridical or positive sense, but I am referring to the workings of a certain regulatory regime, one that informs the law, and one that also exceeds the law. When we ask what the conditions of intelligibility are by which the human emerges, by which the human is recognized, by which some sub- ject becomes the subject of human love, we are asking about conditions of intel- ligibility composed of norms, of practices, that have become presuppositional, without which we cannot think the human at all. So I propose to broach the rela- tionship between variable orders of intelligibility and the genesis and knowability of the human. And it is not just that there are laws that govern our intelligibility, but ways of knowing, modes of truth, that forcibly define intelligibility. This is what Foucault describes as the politics of truth, a politics that per- tains to those relations of power that circumscribe in advance what will and will not count as truth, that order the world in certain regular and regulatable ways, and that we come to accept as the given field of knowledge. We can understand the salience of this point when we begin to ask: What counts as a person? What counts as a coherent gender? What qualifies as a citizen? Whose world is legiti- mated as real? Subjectively, we ask: Who can I become in such a world where the meanings and limits of the subject are set out in advance for me? By what norms am I constrained as I begin to ask what I may become? What happens when I begin to become that for which there is no place in the given regime of truth? This is what Foucault describes as “the desubjugation of the subject in the play of . -

Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Incontinence in Childhood

Committee 9 Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Incontinence in Childhood Chairman S. TEKGUL (Turkey) Members R. JM NIJMAN (The Netherlands), P. H OEBEKE (Belgium), D. CANNING (USA), W.BOWER (Hong-Kong), A. VON GONTARD (Germany) 701 CONTENTS E. NEUROGENIC DETRUSOR A. INTRODUCTION SPHINCTER DYSFUNCTION B. EVALUATION IN CHILDREN F. SURGICAL MANAGEMENT WHO WET C. NOCTURNAL ENURESIS G. PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF URINARY INCONTINENCE AND ENURESIS IN CHILDREN D. DAY AND NIGHTTIME INCONTINENCE 702 Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Incontinence in Childhood S. TEKGUL, R. JM NIJMAN, P. HOEBEKE, D. CANNING, W.BOWER, A. VON GONTARD In newborns the bladder has been traditionally described as “uninhibited”, and it has been assumed A. INTRODUCTION that micturition occurs automatically by a simple spinal cord reflex, with little or no mediation by the higher neural centres. However, studies have indicated that In this chapter the diagnostic and treatment modalities even in full-term foetuses and newborns, micturition of urinary incontinence in childhood will be discussed. is modulated by higher centres and the previous notion In order to understand the pathophysiology of the that voiding is spontaneous and mediated by a simple most frequently encountered problems in children the spinal reflex is an oversimplification [3]. Foetal normal development of bladder and sphincter control micturition seems to be a behavioural state-dependent will be discussed. event: intrauterine micturition is not randomly distributed between sleep and arousal, but occurs The underlying pathophysiology will be outlined and almost exclusively while the foetus is awake [3]. the specific investigations for children will be discussed. For general information on epidemiology and During the last trimester the intra-uterine urine urodynamic investigations the respective chapters production is much higher than in the postnatal period are to be consulted. -

In Re Marriage of Simmons: a Case for Transsexual Marriage Recognition Katie D

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 37 Article 4 Issue 3 Spring 2006 2006 In re Marriage of Simmons: A Case for Transsexual Marriage Recognition Katie D. Fletcher Loyola University Chicago, School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Katie D. Fletcher, In re Marriage of Simmons: A Case for Transsexual Marriage Recognition, 37 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 533 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol37/iss3/4 This Mentorship Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In re Marriageof Simmons: A Case for Transsexual Marriage Recognition Katie D. Fletcher* mentored by Judge Lola Maddox** I. INTRODUCTION It's a girl! It's a boy! At birth, every individual is identified as either male or female, usually by visual examination.1 Gender and sex are typically unambiguous and most people consider them the same.2 The * J.D., Loyola University Chicago, expected January 2007. Mom and Carol, thank you for your never-ending love and support, you both inspire and spur me. This Article would not be what it is today without the invaluable assistance from the Loyola University Chicago Law Journal editorial board and members. Additionally, special thanks and gratitude to the Honorable Judge Maddox for providing insight and for encouraging and challenging me throughout the process. Finally, this Article would not have been possible without contributions in many different forms and for that I am grateful to Professor Cynthia Ho and Jody Marksamer. -

EAU-Guidelines-On-Paediatric-Urology-2019.Pdf

EAU Guidelines on Paediatric Urology C. Radmayr (Chair), G. Bogaert, H.S. Dogan, R. Kocvara˘ , J.M. Nijman (Vice-chair), R. Stein, S. Tekgül Guidelines Associates: L.A. ‘t Hoen, J. Quaedackers, M.S. Silay, S. Undre European Society for Paediatric Urology © European Association of Urology 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 8 1.1 Aim 8 1.2 Panel composition 8 1.3 Available publications 8 1.4 Publication history 8 1.5 Summary of changes 8 1.5.1 New and changed recommendations 9 2. METHODS 9 2.1 Introduction 9 2.2 Peer review 9 2.3 Future goals 9 3. THE GUIDELINE 10 3.1 Phimosis 10 3.1.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 10 3.1.2 Classification systems 10 3.1.3 Diagnostic evaluation 10 3.1.4 Management 10 3.1.5 Follow-up 11 3.1.6 Summary of evidence and recommendations for the management of phimosis 11 3.2 Management of undescended testes 11 3.2.1 Background 11 3.2.2 Classification 11 3.2.2.1 Palpable testes 12 3.2.2.2 Non-palpable testes 12 3.2.3 Diagnostic evaluation 13 3.2.3.1 History 13 3.2.3.2 Physical examination 13 3.2.3.3 Imaging studies 13 3.2.4 Management 13 3.2.4.1 Medical therapy 13 3.2.4.1.1 Medical therapy for testicular descent 13 3.2.4.1.2 Medical therapy for fertility potential 14 3.2.4.2 Surgical therapy 14 3.2.4.2.1 Palpable testes 14 3.2.4.2.1.1 Inguinal orchidopexy 14 3.2.4.2.1.2 Scrotal orchidopexy 15 3.2.4.2.2 Non-palpable testes 15 3.2.4.2.3 Complications of surgical therapy 15 3.2.4.2.4 Surgical therapy for undescended testes after puberty 15 3.2.5 Undescended testes and fertility 16 3.2.6 Undescended -

Pediatric Urology Fellowship Program UCSF Goals and Objectives

Revised July 24, 2017 Pediatric Urology Fellowship Program UCSF Goals and Objectives Summary: The Pediatric Urology Felllowship at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital consists of one year of clinical pediatric urology (accredited by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and one year of research (laboratory based or clinical outcomes or a combination). The ACGME-accredited clinical program takes place at mainly at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital’s San Francisco Mission Bay site and Oakland site. The educational goals are the same at each site and follow the ACGME program requirements (Revised Common Program Requirements effective: July 1, 2016) Areas of Education: Specialized training in Pediatric Urology at UCSF covers all aspects of congenital urologic anomalies including prenatal diagnosis, childhood-acquired urologic problems such as urinary tract infection, tumors and trauma and urologic problems of adolescence. The subspecialty training in pediatric urology provides an experience of sufficient level for the trainee to acquire advanced skills in the management of congenital anomalies and pediatric urologic problems. Broadly, the goals and objectives of the UCSF training program in Pediatric Urology are to assure that each of the trainees receives an in depth theoretical and practical education in the various domains of Pediatric Urology. This training is expected to provide the graduate with an excellent background in all aspects of Pediatric Urology such that the individual on graduation is competent to practice independently, pediatric urology. Specific Educational Goals and Objectives: 1. Open Surgery: Experience in all aspects of pediatric surgery in the child with a urological problem. This includes major reconstructive, renal, ureteral, bladder and urethral surgery. -

Experimentally Induced Testicular Dysgenesis Syndrome Originates in the Masculinization Programming Window

Experimentally induced testicular dysgenesis syndrome originates in the masculinization programming window Sander van den Driesche, … , Niels E. Skakkebaek, Richard M. Sharpe JCI Insight. 2017;2(6):e91204. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.91204. Research Article Endocrinology Reproductive biology The testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS) hypothesis, which proposes that common reproductive disorders of newborn and adult human males may have a common fetal origin, is largely untested. We tested this hypothesis using a rat model involving gestational exposure to dibutyl phthalate (DBP), which suppresses testosterone production by the fetal testis. We evaluated if induction of TDS via testosterone suppression is restricted to the “masculinization programming window” (MPW), as indicated by reduction in anogenital distance (AGD). We show that DBP suppresses fetal testosterone equally during and after the MPW, but only DBP exposure in the MPW causes reduced AGD, focal testicular dysgenesis, and TDS disorders (cryptorchidism, hypospadias, reduced adult testis size, and compensated adult Leydig cell failure). Focal testicular dysgenesis, reduced size of adult male reproductive organs, and TDS disorders and their severity were all strongly associated with reduced AGD. We related our findings to human TDS cases by demonstrating similar focal dysgenetic changes in testes of men with preinvasive germ cell neoplasia (GCNIS) and in testes of DBP-MPW animals. If our results are translatable to humans, they suggest that identification of potential causes of human TDS disorders should focus on exposures during a human MPW equivalent, especially if negatively associated with offspring AGD. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/91204/pdf RESEARCH ARTICLE Experimentally induced testicular dysgenesis syndrome originates in the masculinization programming window Sander van den Driesche,1 Karen R. -

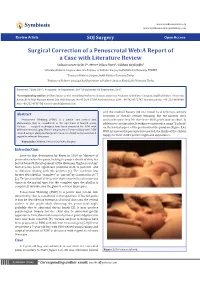

Surgical Correction of a Penoscrotal Web:A Report of a Case With

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Review Article SOJ Surgery Open Access Surgical Correction of a Penoscrotal Web:A Report of a Case with Literature Review Volkan Sarper Erikci1*, Merve Dilara Öney2, Gökhan Köylüoğlu3 1Attending Pediatric Surgeon, Associate Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Sağlık Bilimleri University, TURKEY 2Trainee in Pediatric Surgery, Sağlık Bilimleri University,Turkey 3Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Chief Department of Pediatric Surgery, Katip Çelebi University, Turkey Received: 7 July, 2017; Accepted: 14 September, 2017; Published: 23 September, 2017 *Corresponding author: Volkan Sarper Erikci, Attending Pediatric Surgeon, Associate Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Sağlık Bilimleri University, Kazim Dirik Mah Mustafa Kemal Cad Hakkibey apt. No:45 D.10 35100 Bornova-İzmir. GSM: +90 542 4372747, Business phone: +90 232 4696969, Fax: +90 232 4330756; E-mail: [email protected] and the medical history did not reveal local infection, urinary Abstract retention or chronic urinary dripping. But the parents were Penoscrotal Webbing (PSW) is a penile and scrotal skin anxious because they felt that their child’s penis was too short. In abnormality that is considered in the spectrum of buried penis. Various surgical techniques have been proposed for PSW with on the ventral aspect of the penis solved the problem (Figure 3,4). different terminologies. Herein we present a 7-year-old boy with PSW Withaddition an uneventful to circumcision, postoperative foreskin period,reconstruction the family