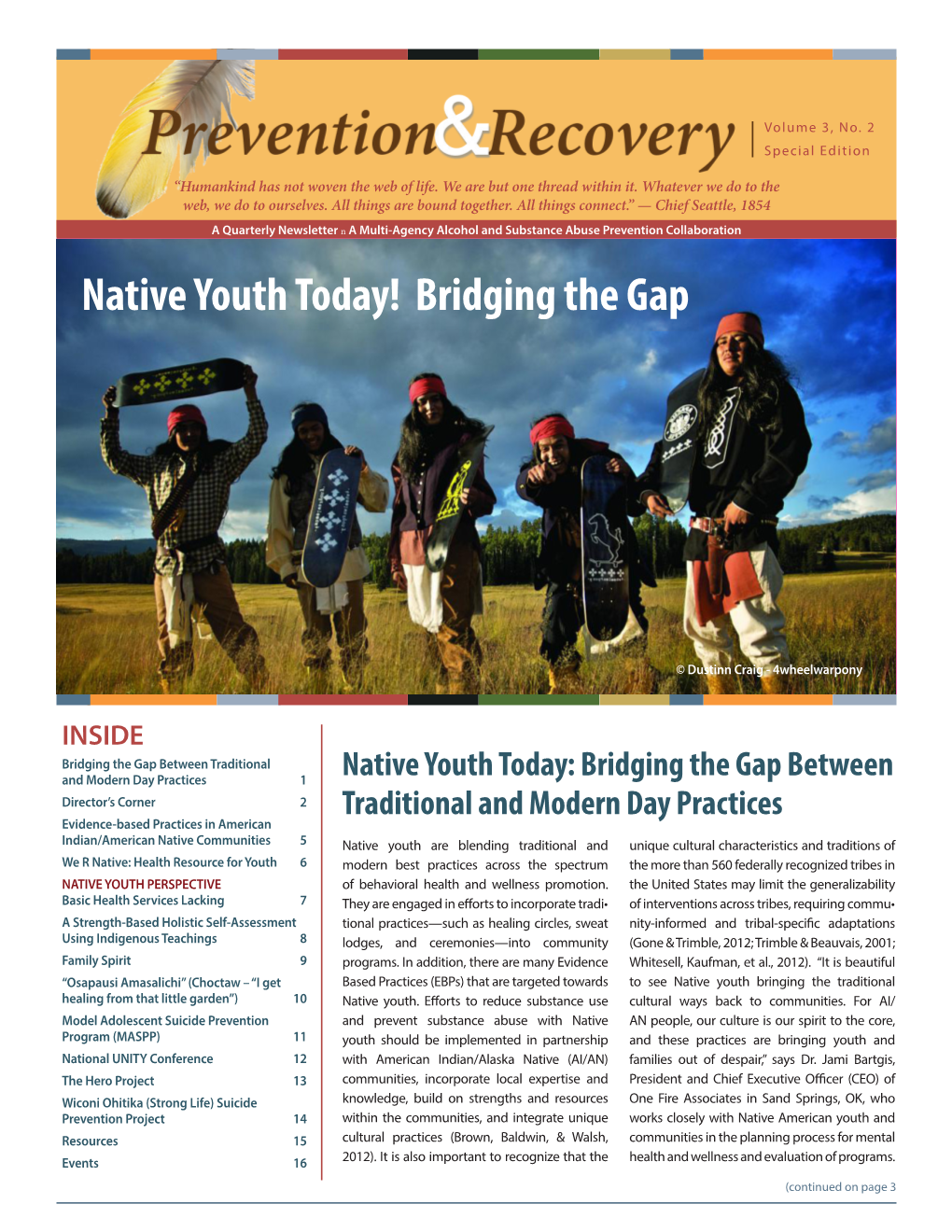

Native Youth Today! Bridging the Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Annual Report

2018 Annual Report Engaging Community Partners to Improve the Lives of Children and Families. Do something to support Community Substance Abuse Awareness P revention 739,454 served Arrive Alive Event Promotes Substance Abuse Prevention and Roadway Safety Prescription One of the best ways to combat impaired driving and roadway Take Back Events crashes is to provide education and awareness to these issues. The Drug Free Community Coalition did just that. Armed with an idea from a one of its members, the Coalition wrote for a small 2,447 lbs. grant through the NW MO Coalition for Roadway Safety and was awarded the grant. On April 25, 2018 the Coalition hosted our first Arrive Alive Event for high school students. Students from Andrew and Buchanan County were invited to enjoy speaker, Reducing Keller Colley from Think First MO. Keller spoke to the students Underage Drinking about substance use and driving while impaired. The students then enjoyed over 20 local vendor booths with hands on activities focusing on substance abuse prevention and roadway safety. The 391 vendors gave the students a wide range of hands on activities compliance checks and demonstrations such as, riding through a construction zone, a driving simulator, what to do when you get pulled over, % breathalyzer demonstrations, share the road with a semi-truck, 90 etc. The Coalition successfully served over 175 students that day success rate from three different schools during this event. Do something to help Crisis Prevention is dedicated to providing services to children and families in an effort to keep them Crisis safe, secure, and thriving. -

The Sound of the Next Generation a Comprehensive Review of Children and Young People’S Relationship with Music

THE SOUND OF THE NEXT GENERATION A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S RELATIONSHIP WITH MUSIC By Youth Music and Ipsos MORI The Sound of the Next Generation THE SOUND OF THE NEXT GENERATION A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S RELATIONSHIP WITH MUSIC By Youth Music and Ipsos MORI Cover Photo: The Roundhouse Trust - Roundhouse Rising Festival of Emerging Music The Sound of the Next Generation The Sound of the Next Generation CONTENTS Foreword – Matt Griffiths, CEO of Youth Music 02 With thanks to 03 Executive summary 04 About the authors 05 A note on terminology 05 The voice of the next generation 06 1) Music is integral to young people’s lives 08 Consumption channels Live music Genres and artists 2) Young people are making music more than ever before 10 Musical engagement Musical learning Music in schools 3) Patterns of engagement differ according to a young person’s background 14 Popular culture and DIY music 4) Music is a powerful contributor to young people’s wellbeing 16 Listening to music and positive emotional states Music to combat loneliness Young people’s view of their future 5) A diverse talent pool of young people supports the future of the music industry 19 Getting a job in the music industry Diversifying the music industry A win-win for education and industry 6) Music has the power to make change for the next generation 21 Appendices 22 Methodology The young musicians The expert interviewees Endnotes 24 01 Photo: The Garage The Sound of the Next Generation The Sound of the Next Generation FOREWORD – MATT GRIFFITHS, So, it’s time to reflect, look back and look forward. -

Why Doesn't Anybody Write Anything About Glam Rock?

WHY DOESN'T ANYBODY WRITE ANYTHING ABOUT GLAM ROCK? Jon Stratton In discussions of post-war British youth cultures glam rock gets very little attention. For example, in their seminal work on British youth cultural forms, Hall et al (1976:54), make only one passing reference to this subculture. In a list of subcultural possessions and objects they refer to: '... the glitter costumes of the Bowrieites ... .' Similarly, Brake (l980:80) in his outlines of British post-war youth cultures gives the culture half a page while skinheads get two pages and rockers one page. Hebdige, (1979) in Subculture: the meaning of style, does spend about two and a half pages looking at glam rock but most of this space is taken up with an analysis of the images of David Bowie. Hebdige writes of Bowie that: Certainly Bowie's position was devoid of any obvious political or counter-cultural significance ... (l979:6l). And Bowie's meta-message was escape — from class, from sex, from obvious commitment — into a fantasy past ... or a science-fiction future (1979:61). What is confusing for Hebdige about glam rock soon becomes clear: In glam-rock, at least amongst those artists placed, like Bowie and Roxy Music, at the more sophisticated end of the glitter spectrum, the subversive emphasis was shifted away from class and youth onto sexuality and gender-typing (1979:61-2). On the one hand, Hebdige can write so much about Bowie because glam rock's presentation of image as image lends itself to Hebdige's dominant semiotic method of analyzing cultural texts. -

Reducing Youth Arrests Keeps Kids Healthy and Successful a Health Analysis of Youth Arrest in Michigan

Reducing Youth Arrests Keeps Kids Healthy and Successful A Health Analysis of Youth Arrest in Michigan June 2017 humanimpact.org Authored By: Kim Gilhuly, MPH Megan Gaydos, MPH Holly Avey, PhD, MPH In partnership with: DeJuan Bland, MOSES Ponsella Hardaway, MOSES Kanzoni Asabigi, Detroit Health Department Jeanette Ball, Michigan Public Health Institute Jason Smith, Michigan Council on Crime and Delinquency Stephen Wade, Washtenaw County Public Health Suggested Citation: Human Impact Partners. June 2017. Reducing Youth Arrests Keeps Kids Healthy and Successful: A Health Analysis of Youth Arrest in Michigan. Human Impact Partners, Oakland, CA. For more information, contact: Kim Gilhuly Human Impact Partners [email protected] www.humanimpact.org 510-452-9442, ext. 114 The work in this report was made possible by the generous funding of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. - 2 - Executive Summary “I just remember thinking oh god I can’t get arrested. I was small when I was a kid and the police looked really big, and I remember thinking I’m not big enough to go where they are trying to take me.” – Former Detroit resident who was arrested as a youth Being arrested as an adolescent can impact a person’s health and life trajectory profoundly. Social policies like zero-tolerance school discipline and neighborhood gang injunctions have led to a proliferation of police surveillance and punishment of common youth misbehaviors. These policies disproportionately impact Black and Latinxi boys and girls living in low-income communities. In the United States, In this report, we evaluate the health and equity impacts of youth 1 in 3 youth have arrest (for kids under the age of 17) in Michigan, with a focus on the been arrested by the city of Detroit, and Wayne and Washtenaw Counties. -

Noise & Capitalism

Cover by Emma (E), Mattin (M) and Sara (S) Noise & Capitalism Noise & Capitalism the interesting part, it’s an you copy another persons E: I was just thinking - you were saying that you Is it possible to try to make than male identified bodies was given at school, she is done this, quite often I have interesting challenge for drawing, where S starts what we’ve been talking weren’t sure if this would something, to capture some- writing in the book. I had studying Graphic Design. S compartmentalised my work our exchange. Now we are and I do a version, and I about, I mean I’ve talked work in relation to the as- thing in design that trans- been involved in an exhibi- sent me the work that she and friendships because I saying that you would do pass it to M, and then that about it with you and with signment you’ve been given, mits the relations produced tion called ‘Her Noise’ at and Brit Pavelson made, it is feel self-conscious or un- the design when maybe you becomes the cover. M, about the projection of because of the time, and the in making this cover? I am the South London Gallery a book that tells in both the generous perhaps. think that we should do the M: Yes it sounds interesting you as the expert and, just amount of time that you & Capitalism Noise struggling with this process in 2005, which in some way text and layout, what are the I started to project that design. -

Music Censorship and the American Culture Wars

Parental Advisory, Explicit Content: Music Censorship and the American Culture Wars Gavin Ratcliffe Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Clayton Koppes Spring Semester 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………….…………….Page II Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….....Page 1 Chapter 1: Censorship and Morality……………………………………………………… Page 10 Chapter 2: Rockin’ and Rollin’ with the PMRC…………………………………………...Page 20 Chapter 3: Killing the Dead Kennedys…………………………………………………….Page 31 Chapter 4: As Legally Nasty as they Wanna Be…………………………………...............Page 40 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….Page 60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..…Page 63 Ratcliffe I Acknowledgements To my grandmother, Jennifer Roff, for 22 years, and counting, of love and support Ratcliffe II Introduction In December, 1984 Tipper Gore bought her 11 year old daughter, Karenna, Prince’s Purple Rain album. Like many other young children, Karenna had heard Prince’s music on the radio and wanted to hear more. Upon listening to the full album Karenna alerted her mother to the provocative nature of some of Prince’s lyrics, such as the track “Darling Nikki,” which contained the lyrics “I knew a girl named Nikki/Guess you could say she was a sex fiend/I met her in a hotel lobby/Masturbating with a magazine.”1 Tipper and Karenna Gore were embarrassed and ashamed that they were listening to such vulgar music, that they were doing so in their home. Deviance and profanity, something that one would expect to find in the street or back alleys had gotten into their home, albeit unwittingly. Tipper Gore soon realized that similar content was being broadcast into their home through other mediums, such as the new, wildly popular Music Television (MTV). -

Youth and Participation Beyond Elections1

Youth and Participation Beyond Elections1 By Russell J. Dalton Sylvia is a senior citizen who lives in Orange County, California. She is deeply interested in politics and votes in every election after studying the candidates and propositions on the ballot. Moreover, she continues her activity between elections. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday she rises at 6AM to call the White House to leave her comments for the president on the issues of the day. On Tuesday and Thursday she either calls her senators from California or the leadership of the House or Senate. Alix lives in northern California. She switched shampoos over animal testing, and will not buy clothes produced by child labor. She yells at people who do not recycle. During her last year in high school she helped organize a protest over the genocide in the Sudan that raised $13,000 for Darfur relief. All this was before she was even eligible to vote. These two individuals show some of the diverse ways in which Americans are politically active. Participation means more than just voting. As previous chapters have argued, a participatory public has been a defining feature of American politics and historically a strength of the political system. Social scientists maintain that political participation “is at the heart of democratic theory and at the heart of the democratic political formula in the United States”.1 Without public involvement in the process, democracy lacks both its legitimacy and its guiding force. In the 1960s and 1970s Americans were actively engaged in voluntary associations, interested in politics, and involved in political discussion. -

Quarter Notes March 2018 • Issue 1

QUARTER NOTES MARCH 2018 • ISSUE 1 Welcome to Quarter Notes, Youth Music Project’s new — and appropriately titled — quarterly newsletter! FEATURES There’s rarely a quiet moment (literally or figuratively) in our bustling musical home, and we’re excited to launch this newsletter to keep you up to date on all STUDENT STORIES the ongoing activities and excitement happening here. 02 Our pilot program, So many folks in the community are making contributions to Youth Music Advanced track, gives Project that are both impactful and inspiring. The In the Spotlight column advanced and teen shines a light on someone who is connected to Youth Music Project and students a new opportunity. helping us grow in new ways. This quarter, I sat down with instructor Ivy Ricci and talked about her timely music video, “Girls Sit Screaming.” We’re also very excited to share Student Stories, where you can learn about 04 IN THE SPOTLIGHT some of the amazing young musicians who are instrumental (pun intended) Instructor Ivy Ricci’s new in making Youth Music Project the unique and special place that it is. It’s music video has a powerful why we’re here, after all. This quarter, we’re highlighting our Advanced Track and inspiring message. Ensemble. This ensemble and our intern band performed to a delighted crowd on the main stage of the Winter Blues Festival earlier this month. This is our second gig at the fest, now in its seventh year, and they generously donated 06 COMMUNITY SUPPORT the event proceeds to Youth Music Project and the Oregon Food Bank. -

Hypnopazuzu Press Release

A transformative union of two idiosyncratic tellers, Hypno- Tibet’s luxurious kosmoi sliding slyly onto peaks of intent and pazūzu sees Current 93 speller David Tibet joining forces with intoxication on the album, and songs such as the Galactic Sexi- the eternal Youth, famed not only for his work as bassist with ness of ‘The Sex Of Stars’ and the Cuneiform Cuteness of ‘The Killing Joke but for production and collaborative work with Auras Are Escaping At The Forest’ show him, backed by the an outlandishly eclectic list of artists from Alien Sex Fiend to emotive and expressive power of Youth’s arrangements, as a Paul McCartney. Together, they’ve created a singular halluci- conduit turning unspelled grammars into grimoires. Nonethe- natory vision that marries symphonic splendour to indignant less, Tibet stresses that his mode of expression here do not gnostic intensity – Create Christ, Sailor Boy draws in, and down, mark a departure from his areas of exploration in Current 93: masks terrestrial and celestial and summons a collection of “There is no difference in terms of the ideas and the dreams songs unlike anything either artist has created previously. and the spheres I used in this album and in this project to anything I have done with any of my other faces. They are all “I first met Youth in the very early ‘80s at a club called the Bat the same face, all 93 of them!” Cave in Soho; I asked Youth to play bass on the first C93 album, Nature Unveiled, which he did,” relates Tibet on this “The group’s name Hypnopazūzu brought together 3 beings, partnership. -

Pig Disease: Similar to Humans, Swine Need to Have Some Basic Living Standards Met in Order to Stay Healthy

ANR Publication 8482 | April 2014 http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu SWINE:From the Animal’s Point of View 4 SUBJECT OVERVIEW AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION There are several factors that can contribute to the deterioration of a pig’s health, but diseases in these animals usually do not occur “out of nowhere.” Illnesses and diseases frequently happen when a pig experiences stress, has a poor diet, is exposed to other pigs that are ill, consumes contaminated food or water, or is housed in an inappropriate environment (i.e., too hot, unsanitary). Some common diseases are pneumonia, pseudo rabies (mad itch), and swine dysentery. Swine can also have external parasites such as lice and mange mites or internal parasites that live inside the pig’s body. Pig Disease: Similar to humans, swine need to have some basic living standards met in order to stay healthy. Having the right diet What You Need to Know is crucial to a pig’s health. A pig that is malnourished is more vulnerable to disease. The immune system of a malnourished animal has a harder time fighting off pathogens (e.g., disease- causing bacteria or viruses) than that of a well-nourished animal, so disease is more likely to take over the underfed pig’s body and bring about still more health problems. A healthy MARTIN H. SMITH, Cooperative Extension Youth Curriculum Development Specialist, University of California, Davis; CHERYL L. diet can prevent myriad diseases. MEEHAN, Staff Research Associate, UC Davis; JUSTINE M. MA, Program Representative, UC Davis; NAO HISAKAWA, Student Assistant, Veterinary Medicine Extension, UC Davis; H. -

Supporting the Needs of Students Involved with the Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice System in the School District of Philadelphia

Supporting the Needs of Students Involved with the Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice System in the School District of Philadelphia JUNE 2014 SOPHIA HWANG, M.S.ED., HEATHER GRIFFIS, PH.D., LIHAI SONG, M.S., DAVID RUBIN, M.D., M.S.C.E. May 30, 2014 In 2006, the Philadelphia Youth Transitions Collaborative Steering Committee commissioned a study on the serious and concerning dropout problem in our schools. The resulting report,Unfulfilled Promise: The Dimensions and Characteristics of Philadelphia’s Dropout Crisis, detailed the educational challenges of students at the highest risk for dropping out of our public schools. The report showed that, although dropping out was a significant issue across all ethnic groups and genders, disconnected and at-risk students, like youth in the juvenile justice system, students in foster care or teens who are pregnant or parenting, were in need of additional educational supports to prevent dropping out. Using the report’s data, a companion policy recommendations report, Turning it Around, was issued. The critical policy outcome was the creation of Project U-Turn, a city-wide initiative aimed at understanding, focusing public attention on, and resolving Philadelphia’s dropout crisis. When I became Mayor in 2008, I set two ambitious, but attainable, educational goals: to double the percentage of Philadelphia residents with a four-year college degree by 2018; and to increase the high school graduation rate to 80% by 2015. Today, our high school graduation rate is 64%, an increase of 11 percentage points over 2007. That change is a step in the right direction, but our Administration knows that there is more work to do, particularly in reducing the dropout rate.