Bringing Robbie Franklin H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maitree Creation

+91-8048371502 Maitree Creation https://www.indiamart.com/maitreecreation/ We “Maitree Creation" is a Sole Proprietorship based firm, engaged as the foremost Manufacturer of Men Brooch, Metal Cufflinks, Pocket Handkerchief & Much More. About Us Established in the year 2016 at Mumbai, Maharashtra. We “Maitree Creation" is a Sole Proprietorship based firm, engaged as the foremost Manufacturer of Men Brooch, Metal Cufflinks, Pocket Handkerchief & Much More. We ensure to timely deliver these products to our clients, through this we have gained a huge clients base in the market. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/maitreecreation/aboutus.html MEN NECKLACE P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Men Stylish Sherwani Men Pearl Necklace Necklace Men Designer Pearl Necklace Men Stylish Pearl Necklace MEN BROOCH P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Men Sherwani Brooch Men Blazer Brooch Men Fancy Coat Brooch Men Stylish Brooch POCKET HANDKERCHIEF P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Blue Check Pocket Designer White Pocket Handkerchief Handkerchief Blue Printed Pocket Fancy White Pocket Handkerchief Handkerchief METAL CUFFLINKS P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Stylish Mild Steel Cufflinks Designer Brass Cufflinks Stylish Stainless Steel Fancy Mild Steel Cufflinks Cufflinks TIE PIN P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Designer Golden Tie Pin Silver Tie Pin Fancy Silver Tie Pin Golden Tie Pin LAPEL PIN P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Designer Lapel Pin Stylish Lapel Pin Fancy Lapel Pin BOW TIE P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Maroon Bow Tie Black Bow Tie Pink Bow Tie P r o OTHER PRODUCTS: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Men Fancy Pearl Necklace Men Designer Coat Brooch Red Printed Pocket Designer Stainless Steel Handkerchief Cufflinks F a c t s h e e t Year of Establishment : 2016 Nature of Business : Manufacturer CONTACT US Maitree Creation Contact Person: Gajendra No. -

Of 36 POLICY 117.1 UNIFORMS, ATTIRE and GROOMING REVISED

POLICY UNIFORMS, ATTIRE AND GROOMING 117.1 REVISED: 1/93, 10/99, 12/99, 07/01, RELATED POLICIES: 405, 101, 101.1 04/02, 1/04, 08/04, 12/05, 03/06, 03/07, 05/10, 02/11, 06/11, 11/11, 07/12, 04/13, 01/14, 08/15, 06/16, 06/17, 03/18, 09/18, 03/19, 03/19, 04/21,07/21,08/21 CFA STANDARDS: REVIEWED: As Needed TABLE OF CONTENTS A. PURPOSE .............................................................................................................................. 1 B. GENERAL ............................................................................................................................. 2 C. UNIFORMS ........................................................................................................................... 2 D. PLAIN CLOTHES/ SWORN PERSONNEL ................................................................... 11 E. INSPECTIONS ................................................................................................................... 11 F. LINE INSPECTIONS OF UNIFORMS ........................................................................... 11 G. FLORIDA DRIVERS LICENSE VERIFICATION PROCEDURES ........................... 11 H. MONTHLY LINE INSPECTIONS REPORT AND ROUTING ................................... 12 I. FOLLOW-UP PROCEDURES FOR DEFICIENCY AND/OR DEFICIENCIES ....... 12 J. POLICY STANDARDS/EXPLANATION OF TERMS ................................................. 12 K. GROOMING ....................................................................................................................... 25 Appendix -

Hammer Prices 21St/22Nd May + Timed Sale - 4Th June 2019

Hammer Prices 21st/22nd May + timed sale - 4th June 2019 Lot No Description 1 An oak canteen containing a 60-piece set of electroplated flatware and cutlery, by Butler of Sheffield. £35.00 2 A canteen of King's pattern epns flatware and cutlery £130.00 3 Two large electroplated candelabra with twin scroll handles, 49 cm high overall (2) £50.00 5 Three silver trophy cups (a/f), 11.7 oz total, to/w a larger electroplated trophy cup, an epns five-piece tea/coffee service, £180.00 rectangular tray, sardine dish with ceramic liner and cover, various epns flatware, etc. 6 A canteen of OEP epns flatware and ivory-handled cutlery (circa 1920), to/w some un-boxed items of flatware and cutlery £40.00 7 A pair of plated on copper candelabra and two pairs of candlesticks, to/w various other electroplated table ware, oval tray, etc. £30.00 A(box) Victorian silver small open salt on hoof feet, a three-piece condiment set, 6.2 oz net weight and a toothpick-pot on weighted 8 foot, to/w a quantity of epns Hanoverian rat-tail flatware in associated canteen, an oblong two-handled tray and six fiddle £110.00 pattern soup spoons 9 A glass pin-dish in the form of a swan with silver head and wings, to/w a four-piece epns tea service, a boxed Ronson 'Milady' £65.00 AVaraflame good quality cigarette Victorian lighter cased with four-piece mother-of-pearl set of mountsparcel gilt (apparently epns servers, unused), to/w a pairset of of dress Georgian buttons, cast etc. -

About Dive Flag Jewelry Let the World Know You're a Diver!

About Dive Flag Jewelry Each item features the classic dive flag inlaid into rhodium-plated brass. Use of rhodium means the jewelry has a very durable finish that will not tarnish. The flag is inlaid into channels in the rings and pendants, making the design extremely durable too, since the flag is not just painted or baked on. Use of simulated inlay in Dive Flag Jewelry protects our reefs! Let the world know you’re a diver! WHOLESALE PRICE LIST Hat/Lapel/Tie Pin Ring $7.50 $20 Sizes: 4.5-14.5 Pendant with Chain Pendant with Leather Cord Pendant with $12.50 $12.50 18” Neck Ring Sizes: 16” & 18” Sizes: 17.5–19” & 20-21.5” $12.50 side attachment In-Line Pendant with Chain $12.50 Sizes: 16” & 18” top attachment Earrings (post) Earrings (French ear wire) O-Ring Bracelet/Anklet Key Ring $15 $22.50 $17.50 $12.50 Surgical steel posts Surgical steel ear wires Sizes: 7”or 8” (side), 9” (top) Horseshoe or Snake Chain Minimum wholesale order: $250 $150 through November 30, 2020 Use COUPON CODE WSALE150 Suggested Wholesale Package: Suggested Wholesale Package: Suggested Wholesale Package Basic (without rings) Standard (without rings) Enhanced Qty Product Each Total Qty Product Each Total Qty Product Each Total 0 Rings $20.00 $0.00 0 Rings $20.00 $0.00 11 Rings $20.00 $220.00 1 Key Ring $12.50 $12.50 2 Key Rings $12.50 $25.00 2 Key Rings $12.50 $25.00 5 Necklaces $12.50 $62.50 8 Necklaces $12.50 $100.00 9 Necklaces $12.50 $112.50 2 Bracelets/Anklets $17.50 $35.00 3 Bracelets/Anklets $17.50 $52.50 3 Bracelets/Anklets $17.50 $52.50 1 Hat/Lapel/Tie Pin $7.50 $7.50 2 Hat/Lapel/Tie Pin $7.50 $15.00 2 Hat/Lapel/Tie Pin $7.50 $15.00 1 pr Earrings (post) $15.00 $15.00 1 pr Earrings (post) $15.00 $15.00 2 pr Earrings (post) $15.00 $30.00 1 pr Earrings. -

Octus Enterprises

+91-8048084137 Octus Enterprises https://www.indiamart.com/octusenterprises/ We are a recognized organization of the industry, involved in manufacturing, trading and wholesaling a commendable array of Trophies and Metal Products. About Us Established in the year 2009, We "Octus Enterprises" established ourselves as a prominent and reliable organization of the industry by manufacturing, trading and wholesaling a wide array of Trophies and Metal Products. Under our quality approved the collection of products we are presenting Metal Badges, Name Plate, Lapel Pin, Brass Letter, Steel Letter, Awards Trophy, Printed T Shirts etc. Offered products are manufactured from top quality components with following industry norms and standards. Our offered products are highly admired by the customers for their long service life, easy to use, high quality and excellent finishing standards. Apart from this, we are offering these products at affordable rates within the assured period of time. We have constructed a highly advanced and well-equipped infrastructure unit. Our manufacturing unit is equipped with all the required machines and tools. Also, we have hired a team of qualified professionals to handle all our business operations. We have hired our team after assessing their previous working experiences and domain knowledge. All our offered products are passed through stringent quality checking procedures to ensure their quality. Apart from this, regular seminars and training programs are conducted to keep our team members updated with the prevailing -

Sukho International

+91-8048372562 Sukho International https://www.indiamart.com/daccessories/ We are engaged in manufacture, trader and wholesaler a complete solution of Bow Ties, Self Bow Ties, Pocket Squares, Floral and Metal Lapel Pin, Designer Neck Ties, TAC Pin Brooches, Tie Pins, Collar Bars, Luxury Brooch and much more. About Us Established in 2001, "DAccessories (Unit of Sukho International)" is one of the reckoned enterprises of the nation readily indulged in manufacture, trader and wholesaler a wide variety of Bow Ties, Self Bow Ties, Pocket Squares, Floral and Metal Lapel Pin, Designer Neck Ties, TAC Pin Brooches, Tie Pins, Collar Bars, Luxury Brooch, Shirt Cufflinks and much more. The products we offer are made in close exactness with the pre-set principles of supremacy using top- notch material and sophisticated techniques. Also, these products are credited among our honored customers for superiority & rugged design and help us to receive a notable standing in this vast competitive market. We have developed and designed products, which fulfill the needs of diverse markets. Our employees are fully aware with the needs & requirements of our clients so they are processing products accordingly & we offer them at cost effective price range. All our products are in complete sync to the quality parameters and made under the supervision of best quality experts of this domain. Also, we make sure that all our products delivered to the clients end in a timely manner. In this task our well connected distribution network helps us a lot. Under the able guidance of our mentor, "Mr. Deepjot S. Rekhi", we have been able to garner the trust and confidence of a large number of patrons. -

9900 Dutch Contents 2

Pool Table, Tools, Wood, Metal, Jewelry, Glass, Antiques, Watches, Currency, Toys, Patio Furniture, and Home Decor Assets BeingOnline Sold To Settle The EstateContent of Betty Dick, Lucas CountyAuction Probate #2021 EST 001177 Bidding Ends: Tuesday, July 20, 2021 at 10:00 am ONLINE BIDDING ENDS: Inventory List TUESDAY, JULY 20, 2021 AT 10:00 AM # Title Description 280 WS- Sterling Silver Women’s Bracelet Marked “Sterling” With A Marking Of A Clover With U N E In Each Of The 3 Leaves, Appears No Damage 300 Out- Metal Scrap Pile #1 North 301 Out- Metal Scrap Pile #2 South 400 WS- Antique Airplane Dornier DO-X Flying Boat - Hubley Metal, Appears Complete, Marked “Do-X”, “Hubley” 401 WS- Hubley Cast Iron Tractor Appears Complete, Red Paint Worn 402 WS- Pair of Antique Metal Toys (2) Wheels Missing On Car, Metal Trailer Wagon With (2) Wheels, No Markings 403 WS- Fordson Cast Iron Tractor Marked “Fordson”, Driver And Steering Wheel Missing 404 WS- Antique - The Old English Razor Chips On Handle, Marked “Frederick Renolds, Sheffield” 405 WS- Antique Camera’s And Equipment (2) Brownie Reflex, Kodak, Flash Holders (Some With Damage), None Tested 406 WS- Antique Camera’s Brownie Reflex, Starflash Camera, Hawkeye, Kodak Instamatic Camera, None Tested 407 WS- Lot of Flatware Silver Plate, Stainless, Spoons, Forks, Knives, Simon L and George H Rogers, Carlton, Racebrook, Hall Elton 408 WS- Lot of Pin-On Botton’s Miscellaneous Size And Vintage Buttons 409 WS- Lot of Collectibles Lighters, Baseball Cards, Car Grenade Advertising, Medals, Paperweights, Mignonnette Molgora Keychain, Gyroscope, Pocket Knife 410 MS- Oliverus H. -

Manual and Computer Aided Jewellery Design Training Module

MAST MARKET ALIGNED SKILLS TRAINING MANUAL AND COMPUTER AIDED JEWELLERY DESIGN TRAINING MODULE In partnership with Supported by: INDIA: 1003-1005,DLF City Court, MG Road, Gurgaon 122002 Tel (91) 124 4551850 Fax (91) 124 4551888 NEW YORK: 216 E.45th Street, 7th Floor, New York, NY 10017 www.aif.org MANUAL AND COMPUTER AIDED JEWELLERY DESIGN TRAINING MODULE About the American India Foundation The American India Foundation is committed to catalyzing social and economic change in India, and building a lasting bridge between the United States and India through high impact interventions ineducation, livelihoods, public health, and leadership development. Working closely with localcommunities, AIF partners with NGOs to develop and test innovative solutions and withgovernments to create and scale sustainable impact. Founded in 2001 at the initiative of PresidentBill Clinton following a suggestion from Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee, AIF has impacted the lives of 4.6million of India’s poor. Learn more at www.AIF.org About the Market Aligned Skills Training (MAST) program Market Aligned Skills Training (MAST) provides unemployed young people with a comprehensive skillstraining that equips them with the knowledge and skills needed to secure employment and succeed on thejob. MAST not only meets the growing demands of the diversifying local industries across the country, itharnesses India’s youth population to become powerful engines of the economy. AIF Team: Hanumant Rawat, Aamir Aijaz & Rowena Kay Mascarenhas American India Foundation 10th Floor, DLF City Court, MG Road, Near Sikanderpur Metro Station, Gurgaon 122002 216 E. 45th Street, 7th Floor New York, NY 10017 530 Lytton Avenue, Palo Alto, CA 9430 This document is created for the use of underprivileged youth under American India Foundation’s Market Aligned Skills Training (MAST) Program. -

My Etsy Catalog

The Tie Chest Etsy Catalogue - Jewelry Edition - July 2018 The Tie Chest specializes in collectible neckties and vintage mens jewelry, including tie clips, tie tacks and cufflinks. FREE SHIPPING when you spend $75 or more. thetiechest.etsy.com [email protected] www.facebook.com/thetiechest Ben name vintage tie clip bar Bill name vintage tie clip bar Nefertiti queen egyptian Vintage 1960s s wank tie clip s wank 1950s s wank 1950s revival vintage tie clip bar clas p s hort 3/4" us coin $24.99 $24.99 clas p revers e painted $24.99 $24.99 Vintage tie clip bar green Vintage tie clip bar s ilver tone Vintage s wank 5oc collar bar Vintage tie clip bar colonial enamel over copper 1.75" s igned pioneer as ian man holder 2" bras s tone mens hors eman hors e rider s ilver $18.99 $34.99 jewelry tone 1.25" $19.99 $29.99 Roman trojan s oldier vintage Vintage 1940s tie bar clip Vintage 1960s s wank letter f Womans vintage tie clip bar tie clip clas p bar blue mos aic letter j initial gold tone pierce initial tie clip bar clas p s ilver clas p cottage s cene s ilver circle 3.5cm 1.25" d look s wank tone 1.5" tone 1.75" $19.99 $34.99 $27.99 $19.99 Vintage key s haped tie clip Theater mas ks vintage tie clip Vintage 1968 tie clip clas p Vintage tie clip bar s emi bar claps 1.5" gold tone curtis bar drama theatre wallace name pers onaliz ed trans port truck international ind m-2 eas tlake $34.99 gold tone 1" brotherhood of teams ters $19.99 $24.99 $24.99 Joe name s wank tie clip bar Stylis h woman cameo tie clip Windmill golf club hickok Naval as s ociation -

Download Lot Listing

JEWELRY ONLINE Tuesday, October 20, 2020 DOYLE.COM Doyle New York 1001 1002 Pair of Gold and Diamond Curb Link Pendant- Andrew Clunn Gold and Amethyst Pendant with Gilt- Earclips and Andrew Clunn Hammered Gold and Metal Omega Necklace Faience Ankh Pendant-Earclips 18 kt., one oval amethyst ap. 33.25 cts., pendant 18 kt., 24 round diamonds ap. .45 ct., curb link signed A. Clunn, on gilt-metal necklace. Inner cir. 15 earclips no. 477, 2 faience ankh ap. 27.0 x 14.1 mm., inches. hammered earclips signed A. Clunn, ankh detachable, $600-800 ap. 18.5 dwts. gross. $800-1,200 1003 1004 Hammered Gold, Platinum, Cabochon Amethyst, Tiffany & Co. Pair of Gold Hoop Earclips and Emerald and Diamond Ring Paloma Picasso 'Scribble' Brooch 18 kt., one oval cabochon amethyst ap. 20.25 cts., one 14 & 18 kt., polished hoops signed Tiffany & Co., round cabochon emerald ap. 1.00 ct., 7 round zig-zag signed Tiffany & Co., Paloma Picasso, ap. diamonds ap. .35 ct., shank added to original David 13.8 dwts. Webb element, unsigned, one diamond missing, ap. $650-750 15.5 dwts. Size 6 1/2. $800-1,200 1005 1006 Verdura Stainless Steel and Gold Wristwatch David Yurman Gold and Lemon Chrysoprase Ring 18 kt., automatic, circular blue dial with gold-tone 18 kt., one square cushion-shaped lemon chrysoprase baton and quarter hour Arabic numerals, sweep ap. 20.0 x 19.3 mm., small round diamonds, signed seconds hand, dia. ap. 32 mm., brown leather strap DY, 7, ap. 22.6 dwts. Size 7. -

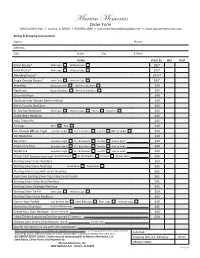

View Order PDF Form

Marian Memories Order Form 1600 Garfield Ave. • Aurora, IL 60506 • 630.896.4986 • [email protected] • www.marianmemories.com Billing & Shipping Information: Name: Phone: Address: City: State: Zip: E-Mail: Items Price Ea. Qty. Total Silver Rosary* With Caps: Without Caps: $85* Gold Rosary* With Caps: Without Caps: $95* Wedding Rosary* $225* Single Decade Rosary* With Caps: Without Caps: $45* Bracelets Rosary Bracelet: Memorial Bracelet: $40 Necklaces Rosary Necklace: Memorial Necklace: $45 Cross Necklace $40 Necklace with Blessed Mother Medal $40 Men’s Crucifix Necklace $40 St. Michael Necklace With Caps: Without Caps: Men’s: Women’s: $50 Single Bead Necklace $40 Holy Trinity Pin $45 Earrings Wire: Post: $40 Car Chaplet OR Car Angel Guardian Angel: St. Christopher: Crucifix: OR: Car Angel: $40 Car Medallion $40 Key Chain Guardian Angel: St. Christopher: Crucifix: Patron Saint: $40 Zippee Key Ring Guardian Angel: St. Christopher: Crucifix: Patron Saint: $40 Bookmark Guardian Angel: St. Christopher: Crucifix: Patron Saint: $40 Prayer Card (Send your prayer card) Guardian Angel: St. Christopher: Crucifix: Patron Saint: $40 Sterling Silver Cross Necklace $50 Sterling Silver Dove Necklace Small Dove: Large Dove: $45 Sterling Silver Cross with Heart Necklace $45 Gold Over Sterling Silver Cross Heart and Crystal $65 Sterling Silver Celtic Knot Necklace $45 Sterling Silver Claddagh Necklace $45 Sterling Silver Tie Pin With Caps: Without Caps: $50 Sterling Silver Heart Necklace $45 Coin in Your Pocket God Be With Me: Celtic Blessings: With Caps: Without Caps: $40 Christmas Ornament Choice of Ornament: $45 Create Your Own Necklace Choice of Charm: $40 *Add $20 for Engraving (Only for starred (*) items): Up to 14 characters. -

Cast Metal Lapel Pins Cast Metal Whatever the Occasion, Your Emblem Beautifully Reproduced in Hand Filled, Coloured … On-Line Enamel Will Be Deeply Appreciated

http://www.torstamp.com/badges/BA-118.pdf Enamel Filled Finishes Cast Metal Lapel Pins Cast Metal Whatever the occasion, your emblem beautifully reproduced in hand filled, coloured … On-Line enamel will be deeply appreciated. Use it as a lapel, sweater, scarf or tie pin. Available Catalogue in gold, silver or antique finishes with soft enamel fill. NO Art Charge … NO Die Charge. Butterfly clutch attached. Individually polybagged. Delivery: 2-3 weeks TAMPEDE Shiny Gold Shiny Silvertone S Lapel Pins. One colour fill. Prices each. FUTURITY Size 100 250 500 1,000 2,500 +Colour 26 1/2" $4.37 $2.74 $2.06 $1.68 $1.38 + $0.15 3/4" 4.88 2.94 2.35 1.89 1.57 + 0.20 1" 5.14 3.21 2.55 2.09 1.78 + 0.20 11/4" 5.74 3.61 2.98 2.53 2.28 + 0.25 Shiny Bronze/ Antique Brass/ Ronald Copper Gold McDonald Pin Attachments House Butterfly Jewellers Clutch Deluxe BRANDY Included Clutch Antique Bronze/ Shiny Black Bar Pin + $1.16 ea Copper Nickel + $0.58 each Corporate Pins Econo Lapel Pins Automated antique finish for low cost and high perceived value. Antique pewter, brass or bronze finishes. Finished in gold or silver with black Econo Lapel Pins. No colour fill. Prices each. background. Single line lettering. Butterfly 3 3 Size 250 500 1,000 2,500 clutch back. Size up to /4" x /8". 1/2" $1.71 $1.28 $1.12 $0.94 Corporate Pins. Brass or silver plated. Prices ea. 3/4" 1.99 1.41 1.15 0.93 Delivery: 2 -3 weeks 100 250 500 1,000 1" 2.28 1.59 1.25 1.05 $4.88 ea.