Dennis Archer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2002 Federal Bar Association - Eastern District of Michigan Chapter - 40 Years of Service to Our Federal Bench and Bar

www.FBAmich.org FBA N ewsletterWinter 2002 Federal Bar Association - Eastern District of Michigan Chapter - 40 years of service to our Federal Bench and Bar Dean Robb to President’s Column Recall Civil Christine Dowhan-Bailey, President Rights History Collegiality and Synergy in the Federal Bar Attorney Dean Robb will be the featured speaker at the Our Chapter was well represented at this year’s Rakow Scholarship Lun- FBA National Convention as Brian Figot, our newly cheon on November 19th at installed (and top vote getter!) Sixth Circuit Vice- the Hotel Pontchartrain in President; Dennis Clark, E.D. Chapter President- Detroit. Robb will discuss his Elect; Geneva Halliday, Appointed Member to the involvement in the Viola National Council; Alan Harnisch, the FBA National Liuzzo civil rights case. delegate to the ABA, and I winged our way to Mrs. Viola Liuzzo Mrs. Liuzzo, a Detroit Dallas at the end of September. This annual business meeting afforded us an resident who participated in opportunity to collaborate with our colleagues from the Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march, was mur- 80-some other chapters. We experienced first- dered on March 25, 1965. The three Ku Klux Klan hand the energy and direction of our FBA leader- members charged with her death were acquitted of mur- ship as the National Council addressed the na- der in state court but were later convicted of civil rights tional issues agenda including the Judicial Pay violations in federal court in Montgomery, Alabama and Initiative and uniform ethical standards for fed- sentenced to 10 years in prison. The Liuzzo family, rep- eral government attorneys. -

Elvin Davenport Papers 1.25 Linear Feet (1 SB, 1MB), 2 OS 1942-1991, Bulk 1942-1977

Elvin Davenport Papers 1.25 linear feet (1 SB, 1MB), 2 OS 1942-1991, bulk 1942-1977 Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Leslie Van Veen on January 16, 2013 Accession Number: UP002362 Creator: Elvin L. Davenport Acquisition: The Elvin L. Davenport Papers were donated to the Walter P. Reuther Library Damon J. Keith Law Collection of African American Legal History by Mildred Davenport Wilson in September and October 2012. Language: Material entirely in English. Access: Collection is open for research. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Restrictions: Researchers may encounter records of a sensitive nature – personnel files, case records and those involving investigations, legal and other private matters. Privacy laws and restrictions imposed by the Library prohibit the use of names and other personal information that might identify an individual, except with written permission from the Director and/or the donor. Notes: Citation style: “Elvin Davenport Papers, Box [#], Folder [#], Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Related Material: Damon J. Keith Papers Oversized items and audiovisual materials (see inventory at end of guide) have been transferred to the Reuther Library’s Audiovisual Department. Originals of signed correspondence from Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Senator Edward Kennedy, and Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court Thurgood Marshall, were placed in the vault. PLEASE NOTE: Folders in this collection are not necessarily arranged in any particular order. The box folder listing provides an inventory based on their original order. Subjects may be dispersed throughout the collection. -

2018 Annual Report

Coleman A. Young Municipal Center Frank Murphy Hall of Justice Lincoln Hall of Justice Mediation Tribunal Penobscot Building Mission of Third Judicial Circuit Court The Court provides accessible and equal justice with timely dispute resolution. Vision of the Future As a national leader in court performance and the administration of justice, the Court is recognized for: • Using innovative and best practices; • Building trust and confidence in the judicial branch; and • Providing exemplary public service, programs, and work environment including professional facilities and effective technology. Core Values • Fair: We are just, impartial, inclusive, and honorable in all we do. • Proactive: We anticipate and prepare in advance for opportunities and challenges. • Responsive: We are flexible and react quickly to changing needs and times. • User-friendly: We are accessible and understandable. • Collaborative: We involve and work well with each other, court users, and partners. THIRD JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OF MICHIGAN ZENELL B. BROWN 711 COLEMAN A. YOUNG MUNIC IPA L CENTER EXECUTIVE COURT ADMINISTRATOR TWO WOODWARD AVENUE (313) 224-5261 DETROIT, MICH IGAN 48226-3413 Dear Chief Judge Kenny: It is my pleasure to present to you Third Circuit Court’s 2018 Annual Report. As you take office as Chief Judge for 2019, I am happy to welcome you with the good news that the Court is on a forward trajectory. I have had an opportunity to review the status of strategic projects and am happy to report that we have completed projects to address courthouse security, ensure professional development, and to pilot statewide eFiling. The work we have completed under Chief Judge Colombo is laudable, and our peers throughout the nation are beginning to take notice. -

For Alumni, Friends and Family of DETROIT COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL

For Alumni, Friends and Family of DETROIT COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL Summer 2004 Remembering Dr. Richard A. Schlegel, DCDS Headmaster Emeritus THE BEEHIVE IS PUBLISHED TWICE ANNUALLY FOR ALUMNI, PARENTS, PAST PARENTS, STUDENTS AND FRIENDS OF DETROIT COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL HEADMASTER GERALD T. HANSEN EDITOR MARY ELLEN ROWE PHOTOGRAPHY SCOTT C. BERTSCHY CLAYTON T. MATTHEWS DEVELOPMENT OFFICE STAFF DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT SCOTT C. BERTSCHY ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT BARBARA A. MOWER AND PARENT RELATIONS DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS KIRA T. MANN ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS JEAN L. CROSSLEY DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS CLAYTON T. MATTHEWS ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS MARY ELLEN ROWE ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT KIMBERLY M. ARNOLD ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT DONNA CRONBERGER ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT JACKIE MARTIN BEEHIVE DESIGN AND PRODUCTION SUSAN BACHMAN ’76, MARKET ARTS Front cover: Dr. Schlegel surrounds himself with Country Day students in 1986. (L-R) Natalie Greenspan ‘86, Bill Passer ‘86, Keith Fenton ‘86, Dr. Schlegel, Dennis Archer ‘86, Kathy Williams ‘87, Carol Gillow Giles ‘86 and David Levine ‘86. Contents BeeHive • Summer 2004 A NOTE FROM THE HEADMASTER 2 16 BEEHIVE CORRECTIONS 3 CAMPUS BRIEFS 3 REMEMBERING DR. SCHLEGEL 6 CLASS OF 2004 COMMENCEMENT 10 2004 HONORS CONVOCATION 12 AS SEEN IN... THE TRAVERSE CITY 13 RECORD EAGLE DCDS NAMED MICROSOFT CENTER 14 23 OF INNOVATION 24 DCDS CELEBRATES THE ARTS 16 BEACH BASH! AUCTION 2004 18 FLAT STANLEY MANIA AT THE 19 LOWER SCHOOL JUNIOR SCHOOL MOOSE 20 REVEALS HIS ROOTS VISITING ARTIST JACK GANTOS WROTE 22 THE BOOK ON STORYTELLING GRADE 7 FLORIDA TRIP 23 A DAY TIMES SPECIAL - HANDS ON 24 DETROIT GIVES BACK TO THE CITY DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS 25 MESSAGE CAREER DAY 2004 26 6 2004 REGIONAL RECEPTIONS 28 THAT’S AMORÉ! FINE DINING WITH 29 ADRIAN TONON ‘91 ALUMNI SPORTS 32 ALUMNI MOTHERS’ LUNCHEON 34 RETIREMENTS 35 CLASS NOTES 37 IN MEMORIAM 45 32 CONTENTS 1 A Note from The Headmaster By Gerald T. -

MS Young, Coleman A. Papers Table of Contents

MS Young, Coleman A. Papers Table of contents Section Page Scope note 2 Biography 3 Research Tool: Chronology 6 Research Tool: City department name changes 9 Research Tool: City departments directors 10 Research Tool: Acronyms and abbreviations key 33 Year: 1973 34 Year: 1974 37 Year: 1975 54 Year: 1976 69 Year: 1977 82 Year: 1978 93 Year: 1979 104 Year: 1980 116 Year: 1981 129 Year: 1982 139 Year: 1983 150 Year: 1984 157 Year: 1985 167 Year: 1986 177 Year: 1987 186 Year: 1988 196 Year: 1989 207 Year: 1990 217 Year: 1991 229 Year: 1992 239 1 MS Young, Coleman A. Papers Finding Aid Bulk 1974-1992 Repository: Detroit Public Library. Burton Historical Collection. Title: Coleman A. Young Mayoral Papers. Dates: 1972-1992 Quantity: 495 linear feet Physical Description: 328 boxes; 1 LMS Collection Number: 5016 Scope and Content: Correspondence and government papers from Coleman A. Young’s four terms as mayor of Detroit. The collection starts with the 1973 election campaign then documents twenty years of government activities as chronicled in memos, reports and letters. The papers are from mayoral staff, directors of city departments, quasi-governmental agencies, businesses, charitable and social welfare groups, citizens and Michigan and the U.S. government. Arrangement: The collection is arranged chronologically, then alphabetically by department or creator. It beings with the 1973 election campaign and ends in 1992, the year before Young left office. Folders titled “Letterhead” contain official stationary not from government entities. This includes businesses, lawyers, charities, associations, organizations and lobbyists. The folders titled “General Correspondence” hold letters from other governments, and some Detroit government responses to citizens letters. -

Proceedings and Index of the 56Th Annual Convention - 1994

Proceedings and Index of the 56th Annual Convention - 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS Monday Morning June 13, 1994 Call to Order—Temporary Chair Dana Christner Invocation—Rabbi Efry G. Spectre Opening Ceremonies Presentation of Colors, National Anthems Introduction of Host Committee Welcome and Greetings Hon. Dennis Archer, Mayor, Detroit, Michigan Frank Garrison, President, Michigan State AFL-CIO Ed Scriboer, President, Metropolitan Detroit AFL-CIO Hon. David E. Bonior, U.S. House of Representatives, 10th Congressional District Bob Johnson, Vice President, District President's Address—International President Morton Bahr Video Presentation—Former President Joseph A. Beirne Use of Microphones Credentials Committee Partial Report Convention Rules Finance Committee Report Recess Monday Afternoon Call to Order Communications Report of the Secretary-Treasurer, Barbara Easterling National Women's Committee National Committee on Equity Annual Journalism Awards Video Presentation—"There's Supposed To Be A Law" Resolutions Committee Report: 56A-94-1—Workers' Rights—Commission on Worker-Management Relations 56A-94-2—The Changing Information Services Industry Constitution Committee Report Organizing Awards President's Annual Award Special Presentation to President Morton Bahr Pediatric AIDS Foundation Awards Announcements Recess Tuesday Morning June 14,1994 Call to Order Invocation—Father Norm Thomas Installation Ceremony John S. Clark, Vice President CWA-NABET Report of Executive Vice President M.E. Nichols Discussion Re: Members' Relief Fund Appeals Committee -

Reginald M. Turner, Jr

STATE OF MICHIGAN STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION RESOLUTION REGINALD M. TURNER, JR. WHEREAS, Reginald “Reggie” M. Turner, the son of Reginald Maurice Turner, Sr., and Annie Laurie Turner moved to Northwest Detroit in 1967; and WHEREAS, Reggie earned his Bachelor of Science degree from Wayne State University in 1982; and his law degree from the University of Michigan Law School in 1987; and WHEREAS, in 1996-97 Reggie completed a White House Fellowship in Washington, D.C. managing a Presidential Task Force and working as an aide to former Housing and Urban Development Secretaries Henry Cisneros and Andrew Cuomo; and WHEREAS, Reggie was appointed to the State Board of Education on September 25, 2003 by Governor Jennifer M. Granholm, filling the unexpired term of Sharon Gire; and WHEREAS, in August 2005, Reggie was elected President of the National Bar Association; and previously served as President of the State Bar of Michigan in 2002-03; and WHEREAS, in November 2006 Reggie was elected to the State Board of Education for an eight year term commencing January 1, 2007 - January 1, 2015; and WHEREAS, during Reggie’s seven year tenure on the State Board of Education, the Board made great improvements in the rigor of the state’s K-12 curriculum, and in the accountability measures that will help to provide quality education to all children across the state; and WHEREAS, Reggie was a compassionate and caring voice for teachers, educational administrators, students, and parents; and WHEREAS, Reggie is active in numerous public service, civic and charitable -

Turning the Neighborhood Inside Out

Turning the Neighborhood Inside Out Imagining a New Detroit in Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project Wendy S. Walters In some senses, the city is like a stage, and the individual is an actor in a drama. By being such an actor, the individual gets a better sense of what the drama is about. —City of Detroit, Planning Department (:) Let the future begin. —Detroit Mayor Dennis Archer (in DeHaven ) it’s just tyree & grandpop out there on Heidelberg Street in the middle of the night turning their neighborhood inside out —John Sinclair (:) Artist Tyree Guyton has said of the rapidly deteriorating houses on Heidel- berg Street: “You’ll think I’m crazy [...] but the houses began speaking to me. [...] Things were going down. You know, we’re taught in school to look at problems and think of solutions. This was my solution” (in Beardsley :). Guyton claims that his painting and decorating of abandoned houses on the block of Heidelberg Street initially began as “protest art” against the de- cline of his eastside Detroit neighborhood. In its controversial years of ex- istence, the Heidelberg Project has also become a performance of history—a didactic representation of past public events and human affairs that makes ma- terial the intricacies of human experience typically not accounted for in con- ventional history or folklore. The Project visually captures the history of a residential community coming undone. Guyton’s houses: literally vomit forth the physical elements of domestic history; furniture, dolls, television sets, signs, toilets, enema bottles, beds, tires, baby buggies come cascading out doors and windows and through holes in the roof, The Drama Review , 4 (T), Winter . -

Detroit's Spruce Goose – City Airport

Mar. 3, 2014 No. 2014-07 ISSN 1093-2240 Available online at mackinac.org/v2014-07 Detroit’s Spruce Goose – City Airport By Michael Farren Summary In 1805, a calamitous fire destroyed the young city of Detroit, giving rise to Detroit’s first task right now should the city’s motto, “Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus” — “We Hope For be recovering from bankruptcy, Better Things; It Shall Rise From the Ashes.” and an important step would be to address the City Airport. After years Today Detroit struggles to recover from a different kind of disaster: of bad policy and mismanagement, Bankruptcy. the airport should either be passed Detroit’s modern downfall came not from natural events, but from adopting to another owner, mothballed, financially ruinous policies, continual mismanagement and failing to change or closed permanently to benefit course, even in the presence of clear signals foretelling a future fiscal collapse. taxpayers most. Main text word count: 657 But one way to move Detroit forward during and after bankruptcy is by unloading municipal assets, especially the assets that have been dragging the city down. By shedding assets, the city can generate or save revenue that might best be used reimbursing creditors — including retirees and pension funds. A good example of such an asset can be found at the city-owned Coleman A. Young International Airport, or City Airport, as it was originally known. The airport has consistently overspent its budget each year for more than two decades, but almost every year the city bailed it out. From 1992 through 2012, Detroit gave the airport subsidies totaling $33.3 million ($42.2 million in 2012 dollars). -

Publius Detroit Guide.CDR

CANDIDATE INTERVIEWS PUBLIUS DETROIT GUIDE 2009 DETROIT PRIMARY CITY COUNCIL This information was compiled as part of theDetroit Open Source Voter Guide Project at no cost to the candidates by volunteers from Publius.org, Citizens for Accountable Council and The Detroit League of Women Voters. More information including updates, video, additional council candidate interviews and charter commissions candidate interviews at: www.publius.org WARNING: THIS DRAFT IS OVER 220 PAGES WHEN PRINTED Questions? Contact Publius.org at (313) 254-4754. Please distribute widely. 2009 Detroit City Council Primary Candidates by ZIP Code Copyright 2009 Publius.org Some Rights Reserved Publius / Detroit League of Women Voters 2009 Detroit Open Source Voter Guide. Please distribute widely. BRENDA GOSS ANDREWS Age: 57 Current Occupation: Retired Detroit Police Deputy Chief; currently licensed Michigan Realtor Education: Howard University, Washington, D.C., Bachelor of Business Administration, minor Economics; Michigan State Univ. E. Lansing, MI, Masters of Science in Criminology; FBI Academy, Quantico, VA; NOrthwestern School of Staff &Command Felony Convictions: None Campaign Website: www.bgossandrews4citycouncil.com Campaign Contact Number: 313‐310‐5194 Why are you running for Detroit City Council? 1 I am running for City Council because I am discouraged by the failed leadership; unprofessional antics; an atmosphere that has been devoid of civility; and the specter of corruption that has swirled around city hall. I am running because the citizens of the city of Detroit deserve better. I am a leader with vision, focus, and fresh ideas. I have a proven track record of accomplishment and have developed and implemented real cost saving and cost cutting strategies. -

The Power's Out: Social Negligence in Detroit, 1973-2003

THE POWER’S OUT: SOCIAL NEGLIGENCE IN DETROIT, 1973-2003 Ryan Arnold A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Nicole Jackson, Advisor Michael Brooks Rebecca Kinney ii ABSTRACT Nicole Jackson, Advisor The Power's Out: Social Negligence in Detroit, 1973-2003 examines the ways in which the city of Detroit has deteriorated in the late twentieth due to the incompetent functionality of the power structure within the city and how they have overlooked the needs of Black inner-city residents. This thesis utilizes a combination of primary sources and secondary sources such as newspaper articles, community organizational records, autobiographies, blog posts, and interviews to contribute a narrative of Detroit that discusses the conditions of Detroit post-1967 into the twenty-first century. Although industrial decline and white flight were major contributors to Detroit’s decline, the negligence of the city administration to provide an inner-city efficient infrastructure, adequate public housing, and proper civic service response and police-community relations. Research about Detroit revealed the city corruption within Coleman A. Young's city administration was vital to the overall decline of Detroit during his twenty-year tenure. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor and mentor, Dr. Nicole Jackson for her outstanding support and belief in my ability to create this thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Rebecca Kinney and Megan Goins-Diouf for additional support, advice and guidance within my research and journey creating this thesis. -

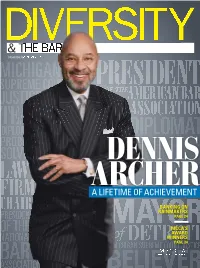

A Lifetime of Achievement

® November/ December 2012 COURT DENNIS ARCHER A LIFETIME OF ACHIEVEMENT DIV E RSITY EXCELLENCE | EDUCATION | EQUITY 0880 MCCA NovDec.indb 1 11/6/12 1:28 PM 11062012133530 DIVERSITY – A KEY INGREDIENT Hunton & Williams LLP congratulates firm partner Fernando Alonso for his selection as a 2 012 Diversity & the Bar Law Firm Rainmaker. At Perkins Coie, diversity is an essential ingredient that helps us create the best solutions for our clients. We value and encourage diverse viewpoints and draw upon them to resolve our clients’ business and legal challenges. Diversity adds perspective and creativity to what we do. It is a key ingredient to our success. “At Hunton & Williams, diversity is one of our greatest assets.” —Wally Martinez, Managing Partner ANCHORAGE · BEIJING · BELLEVUE · BOISE · CHICAGO · DALLAS · DENVER · LOS ANGELES · MADISON · NEW YORK PALO A L T O · PHOENIX · PORTLAND · S A N D I E G O · S A N F R A N C I S C O · S E A T T L E · SHANGHAI · T A I P E I · W A S H I N G T O N , D . C . Contact: 800.586.8441 Perkins Coie LLP ATTORNEY ADVERTISING www.perkinscoie.com Hunton & Williams, 1111 Brickell Avenue, Suite 2500, Miami, FL 33131, 305.810.2500 © 2012 Hunton & Williams LLP www.hunton.com Atlanta Austin Bangkok Beijing Brussels Charlotte Dallas Houston London Los Angeles McLean Miami New York Norfolk Raleigh Richmond San Francisco Tokyo Washington 0880 MCCA NovDec.indb 2 11/6/12 1:28 PM 11062012133530 Hunton & Williams LLP congratulates firm partner Fernando Alonso for his selection as a 2 012 Diversity & the Bar Law Firm Rainmaker.