I “HOW OTHERS HAVE BUILT”: a SKETCH of INDIANAPOLIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial American Freemasonry and Its Development to 1770 Arthur F

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1988 Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development to 1770 Arthur F. Hebbeler III Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hebbeler, Arthur F. III, "Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development to 1770" (1988). Theses and Dissertations. 724. https://commons.und.edu/theses/724 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - ~I lII i I ii !I I I I I J: COLONIAL AMERICAN FREEMASONRY I AND ITS DEVELOPMENT TO 1770 by Arthur F. Hebbeler, III Bachelor of Arts, Butler University, 1982 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 1988 This Thesis submitted by Arthur F. Hebbeler, III in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done, is hereby approved. ~~~ (Chairperson) This thesis meets the standards for appearance and conforms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby approved. -~ 11 Permission Title Colonial American Freemasonry and its Development To 1770 Department History Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the require ments for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the Library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

Demolition and Cleanup

FactSheet Demolition and Cleanup Before starting a demolition, the person or persons in charge must adequately prepare for the task with regard to the health and safety of the workers. These preparatory operations involve the overall planning of the demolition job, includ- ing the methods to be used to bring the structure down, the equipment neces- sary to do the job, and the measures to be taken to perform the work safely. Before doing demolition work, inspect available personal protective equipment (PPE), and select, wear and use the PPE appropriate for the task. Demolition work involves many of the same hazards associated with construc- tion work. However, demolition also poses additional hazards due to unknown factors such as: deviations from the structure's original design, approved or unapproved modifications that altered the original design, materials hidden with- in structural members, and unknown strengths or weaknesses of damaged mate- rials. To counter these unknowns, all personnel involved in a demolition project need to be fully aware of these types of hazards and the safety precautions avail- able to control these hazards. Preliminary Tasks al able to withstand the loads likely to be A written engineering survey must be per- imposed. Debris dropped through holes in formed on each structure being considered for the floor without the use of chutes must be demolition to determine the condition of the completely enclosed with barricades not less framing, floors and walls, and to assess the than 42 inches high and not less than 6 feet possibility of an unplanned collapse of any back from the projected edge of the opening portion of the structure. -

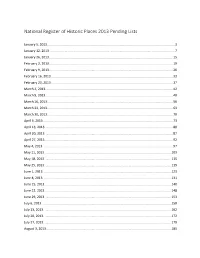

National Register of Historic Places 2013 Pending Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2013 Pending Lists January 5, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 12, 2013. .......................................................................................................................................... 7 January 26, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 February 2, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 February 9, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 26 February 16, 2013. ...................................................................................................................................... 33 February 23, 2013. ...................................................................................................................................... 37 March 2, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 42 March 9, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 48 March 16, 2013. ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Urban Frontier in Pioneer Indiana ROBERT G

The Urban Frontier in Pioneer Indiana ROBERT G. BARROWS AND LEIGH DARBEE ne of the central themes of Richard Wade’s The Urban Frontier— Othat the “growth of urbanism was an important part of the occupa- tion of the West”—has been reflected in Indiana historiography only occasionally. Donald F. Carmony’s examination of the state from 1816 to mid-century is definitive on constitutional, financial, political, and transportation topics, but is much less informative concerning social and urban history; indeed, Wade’s book does not appear in Carmony’s bibliography. In his one-volume history of the state, The Indiana Way, James H. Madison echoes Wade when he writes: “Towns were an essen- tial part of frontier development . providing essential services to the rural and agricultural majority of Indiana’s population.”1 When one con- siders the history of cities and towns in pioneer Indiana in relation to Wade’s classic work, a “generation gap” becomes readily apparent. Developments in Indiana (and, notably, in Indianapolis, the closest comparison to the cities Wade examined) run two or three decades behind his discussion of urbanism in the Ohio Valley. Wade begins his __________________________ Robert G. Barrows is chair of the Department of History at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and co-editor, with David Bodenhamer, of The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). Leigh Darbee is executive assistant at the Indiana Rail Road Company, Indianapolis, and the author of A Guide to Early Imprints at the Indiana Historical Society, 1619- 1840 (2001). 1Richard C. Wade, The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), 2; Donald F. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 1992

United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE P.O. BOX 37127 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20013-7127 IN aEPLy a£F£K TO: The Director of the Natlonal Park service is pleased to Inform you that the fol lowing properties have been entered In the National Register of Historic Places. For further Information cal I 202/343-9542. JAN 3 1992 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/23/91 THROJc:>1 12/27/91 KEY: state. county, ProPerty Name. Address/soundary, City, vicinity, Reference Nuntier N-IL status. Action, Date, MUitipie Name ARIZONA. c.ocoNINO co..NTY. Fjrst Baptist church, 123 s. Beaver St .• Flagstaff. 91001576, IIOMINATION, 12/23/91 ARIZONA, COCONINO COl.NTY. Pendley Homestead Historic District. us 89-A, 7 ml.Nor Sedona. Sedona vicinity, 91001857, NOMINATION, 12/23/91 CALIFORNIA, ALAMEDA COlNTY, The Bellevue-Staten. 492 Staten Ave .. 0akland. 91001896, NOMINATION. 12/27/91 CALIFORNIA, ORANOE CQU,ITY, Casa Romantica. 415 Avenlda cranada, San Clemente. 91001900. NOMINATION, 12/27/91 COLORADO, MONTEZUMA CQU,ITY, Mancos High school, 350 crand AVe., Mancos. 91001740. NOMINATION, 12/23/91 IDAHO. CARIBCX.J cou,rry_ Largllliere, Edgar waiter sr. HOuse. 30 west second south st .• soda Springs. 91001870. NOMINATION. 12/23/91 INDIANA, MARION oou,rTY. St. Clair. 109 w. ~t. Clair St., Indianapolis, 83000085. REMOVAL. 12/04/91 (Apartments and Flats of oowntown Indianapolis TR) IOWA. ALLAMAKEE cou,rry, Lans jng Fisher les Bui !ding. Between co. HWy. X-52 and the Miss lss lppi R.. south uns ing. Lans Ing, 91001832. NOMINATION, 12/23/91 <conservation Movement in 1owa MPS) IOWA. -

Upset City: Ballard's Shock Wave

V14 N14 Wednesday, Nov. 7, 2007 Upset City: Ballard’s shock wave 15 incumbent mayors fall across the state, sending a defiant message to Statehouse By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS - Republican mayor-elect Greg Ballard took the stage at the Murat on Election night and told a frenzied crowd, “Welcome to the biggest upset in Indiana political history! This is a classic, if not the ultimate, example of grassroots politics.” Ballard’s upset of Mayor Bart Peterson was one of at least 15 incum- bents who were defeated Tuesday. This will jolt the Indiana political establishment and send a shudder through the Indiana Republican Greg Ballard forged what he called the “biggest upset” in Hoosier history Statehouse which must come up with a when he deposed Indianapolis Mayor Bart Peterson Tuesday. (HPR Photo by Brian A. property tax solution in 2008 or face a Howey) similar scenario a year from now. Incumbent mayors in Terre Washington, Huntingburg and Frankfort were upset as vot- Haute, Anderson, LaPorte, Delphi, West Lafayette, Tell City, Franklin, Madison, Charlestown, Plymouth, Vincennes, See Page 3 Hoosiers are changing By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS - My competitor at Indiana Legisla- tive Insight likes to propagate the notion that Hoosiers are “resistant to all change.” “Ballard shouldn’t have an Allow me to retort. Since May 2004, Hoosiers have voted out Senate inaugural ball. He should have an Finance Chairman Larry Borst, Gov. Joe Kernan, and Senate President Pro Tempo- amnesty ball.” re Robert D. Garton. The Indiana House has switched hands, meaning we’ve had - Former Indiana two speakers in that time span. -

Counter-Terrorism and the Law

WINTER 2009 IU Indianapolis LAW Alumni Magazine & Dean’s Report Defending the Homeland: Counter-terrorism and the Law INDIANA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW – INDIANAPOLIS Message from the Dean I AM PLEASED TO PRESENT THE WINTER ISSUE of the IU Law–Indianapolis Alumni Magazine and Dean’s Report. The fall semester has been a busy one at the law school, as this magazine attests. In the following pages, you will read about the groundbreaking counter-terrorism simulation that took place at the school in October as part of Professor Shawn Boyne’s Seminar in National Security Law. During the simulation, students played the roles of government officials responding to simulated terrorist attacks across the country and right here in Indianapolis. In January, WFYI, the local PBS affiliate, will air a documentary about this event. The magazine also includes information about the new legal clinic in Eldoret, Kenya, that our school has helped to establish and continues to support. I had the honor of visiting the clinic in October and am in awe of what has been accomplished there in a very short time. You will also read about and see photos of the recent Board of Visitors Reception at the school, hosted by law school alumnus, and former U.S. Vice President, Dan Quayle. We had a packed house for the event that brought many friends back to the school to visit and reminisce. I also want to take a moment to remember our beloved Professor Mary Harter Mitchell, whose sudden and untimely passing in November of this year leaves a tremendous void in our law school family. -

Interior Architectural Design for Adaptive Reuse in Application of Environmental Sustainability Principles

sustainability Concept Paper Interior Architectural Design for Adaptive Reuse in Application of Environmental Sustainability Principles Magdalena Celadyn Faculty of Interior Design, Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, pl. Matejki 13, 31-157 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] Received: 3 June 2019; Accepted: 10 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: The paper discusses an interior architectural design model to enable the accomplishment of sustainable design strategy of efficient resources/waste management. The proposed design concept, referred to as interior architectural design for adaptive reuse, is based on the reintroduction of reclaimed or salvaged building construction materials and products acquired from demolished or refurbished building structural portions, into the structure of interior components. The presented design approach puts circular design methods and techniques in interior design practice at the core of environmentally responsible architectural design. To achieve its objectives, the implementation of resources efficiency strategy into the interior design scheme should remain a decisive interior design quality criterion. Meanwhile, the issues related to the environmental contextualization of interior spaces and their constitutive components, in fulfilment of sustainable design requirements for the conservation of natural resources, are neither sufficiently recognized by interior designers, nor appropriately highlighted in the current design practice. The main purpose of this concept paper is to develop a theoretical scheme for systemic inclusion of interior architectural design for adaptive reuse into the environmentally sustainable interior architectural design framework. This study provides interior designers with the concept of interior components design for the fulfilment of resources efficiency and waste management effectiveness. Keywords: sustainable architectural design; sustainable interior design; interior components; adaptive reuse; environmental contextualization 1. -

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: a Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick 334 N. Senate Avenue, Suite 300 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick March 2015 15-C02 Authors List of Tables .......................................................................................................................... iii Jessica Majors List of Maps ............................................................................................................................ iii Graduate Assistant List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv IU Public Policy Institute Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Key findings ....................................................................................................................... 1 Sue Burow An eye on the future .......................................................................................................... 2 Senior Policy Analyst Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 IU Public Policy Institute Background ....................................................................................................................... 3 Measuring the Use of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene -

50 Properties Listed in Or Determined Eligible for the NRHP Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6

Properties Listed In or Determined Eligible for the NRHP Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 (NR-2410; IHSSI # 098-296-01173), 1801 Nowland Avenue The Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 was listed in the NRHP in 2016 under Criteria A and C in the areas of Architecture and Education for its significance as a Carnegie Library (Figure 4, Sheet 8; Table 20; Photo 43). Constructed in 1911–1912, the building consists of a two-story central block with one-story wings and displays elements of the Italian Renaissance Revival and Craftsman styles. The building retains a high level of integrity, and no change in its NRHP-listed status is recommended. Photo 43. Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 (NR-2410; IHSSI # 098-296-01173), 1801 Nowland Avenue. Prosser House (NR-0090; IHSSI # 098-296-01219), 1454 E. 10th Street The Prosser House was listed in the NRHP in 1975 under Criterion C in the areas of Architecture and Art (Figure 4, Sheet 8; Table 20; Photo 44). The one-and-one-half-story cross- plan house was built in 1886. The original owner was a decorative plaster worker who installed 50 elaborate plaster decoration throughout the interior of the house. The house retains a high level of integrity, and no change to its NRHP-listed status is recommended. Photo 44. Prosser House (NR-0090; IHSSI # 098-296-01219), 1454 E. 10th Street. Wyndham (NR-0616.33; IHSSI # 098-296-01367), 1040 N. Delaware Street The Wyndham apartment building was listed in the NRHP in 1983 as part of the Apartments and Flats of Downtown Indianapolis Thematic Resources nomination under Criteria A and C in the areas of Architecture, Commerce, Engineering, and Community Planning and Development (Figure 4, Sheet 1; Table 20; Photo 45). -

Construction and Demolition Waste Reduction and Recycling Tips

RETHINKING DEBRIS The Industry: Construction and Demolition Waste Reduction and recycling Tips An Opportunity There is money lying virtually ignored on the ground at construction and demolition sites across Wisconsin. Second-hand wood flooring, odd cut lumber, siding scraps, used asphalt shingles, surplus drywall, spent corrugated cardboard and other materials typically labeled waste have value that only a few enterprising companies appreciate. If your business builds, renovates or remodels anything from hospitals to single-family homes, furniture or playground equipment, read on. Find out how to put that money on the ground into your pocket, while helping to conserve natural resources. Wisconsin's Wastestream Precise figures are hard to come by, but industry experts estimate that construction waste and demolition debris (C & D) may account for more than a quarter of our nation's entire wastestream. In some areas of Wisconsin, such as Dane County, analysts estimate that up to 45 percent of all landfilled waste is construction and demolition debris. As disposal costs increase, businesses that divert more of their construction waste and demolition debris from the wastestream by reducing, reusing and recycling can save money and help stimulate markets to handle their wastes. In addition to profits, there is also the law to consider. The Waste Reduction and Recycling Law Wisconsin's Waste Reduction and Recycling Law, signed by Governor Tommy Thompson in 1990, was created to help change the state's throw-away habits. Items banned entirely from state landfills and municipal solid waste incinerators include: major appliances, used motor oil, lead-acid vehicle batteries, yard wastes, corrugated cardboard, office paper, magazines, newspaper, aluminum, steel, bi-metal and glass containers, plastic containers (PETE/#I & HDPE/#2) and waste tires. -

Pence Timeline: Legislature, Then 2016

V20, N8 Thursday Oct. 2, 2014 Pence timeline: Legislature, then 2016 Gov. Pence at a forum at Governor planning reelect, but the Aurora City Hall before taking a selfie with a will weigh all options next May constituent. (HPI Photo by By BRIAN A. HOWEY Brian A. Howey) MADISON, Ind. – The $1 billion question on the minds of Hoosier pundits and voters is whether April 30. Senior Pence political advisers tell HPI that will be Gov. Mike Pence will seek a presidential nomination in the point when Pence sits down with his family and inner 2016. circle and surveys the political landscape both in Indiana and the U.S. The answer, my friends, won’t be blowin’ in the wind until after the Indiana General Assembly sine die next Continued on page 3 Delegation & leadership By BRIAN A. HOWEY WASHINGTON – The two Democrats in the In- diana congressional delegation sounded what could be perceived as alarm. U.S. Rep. André Carson characterized members of Congress as a collection of “nar- “Here’s the issue. Our elections cissists,” a charge sometimes leveled at journalists. A few here in Indiana need to be better, minutes later, delegation dean and they need to work better for U.S. Rep. Pete Visclosky talked of the new routine of funding the people of Indiana.” the government. “Continuing resolutions are a sign of failure,” - Beth White, Democratic Visclosky resolutely stated. secretary of state nomi- These observations, made at a recent Indiana Chamber nee Fly-In event at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center that included both Page 2 is a non-partisan newslet- ter based in Indianapolis and Nashville, Ind.