Geography of British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Vancouver Regional District

Greater Vancouver Regional District The Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) is a partnership of 21 municipalities and one electoral area that make up the metropolitan area of Greater Vancouver.* The first meeting of the GVRD's Board of Directors was held July 12, 1967, at a time when there were 950,000 people living in the Lower Mainland. Today, that number has doubled to more than two million residents, and is expected to grow to 2.7 million by 2021. GVRD's role in the Lower Mainland Amidst this growth, the GVRD's role is to: • deliver essential utility services like drinking water, sewage treatment, recycling and garbage disposal that are most economical and effective to provide on a regional basis • protect and enhance the quality of life in our region by managing and planning growth and development, as well as protecting air quality and green spaces. GVRD structure Because the GVRD serves as a collective voice and a decision-making body on a variety of issues, the system is structured so that each member municipality has a say in how the GVRD is run. The GVRD's Board of directors is comprised of mayors and councillors from the member municipalities, on a Representation by Population basis. GVRD departments are composed of staff and managers who are joined by a shared vision and common goals. Other GVRD entities Under the umbrella of the GVRD, there are four separate legal entities: the Greater Vancouver Water District (GVWD); the Greater Vancouver Sewerage and Drainage District (GVS&DD); the Greater Vancouver Housing Corporation (GVHC), and the Greater Vancouver Regional District. -

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area A collaboration in support of teachers in and around Abbotsford, B.C. in celebration of National Science and Technology Week October 25, 2013 MineralsEd and Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada Led by David Huntley, PhD, GSC and David Thompson, P Geo 1 2 Fraser Valley Geotour Introduction Welcome to the Fraser Valley Geotour! Learning about our Earth, geological processes and features, and the relevance of it all to our lives is really best addressed outside of a classroom. Our entire province is the laboratory for geological studies. The landscape and rocks in the Fraser Valley record many natural Earth processes and reveal a large part of the geologic history of this part of BC – a unique part of the Canadian Cordillera. This professional development field trip for teachers looks at a selection of the bedrock and overlying surficial sediments in the Abbotsford area that evidence these geologic processes over time. The stops highlight key features that are part of the geological story - demonstrating surface processes, recording rock – forming processes, revealing the tectonic history, and evidence of glaciation. The important interplay of these phenomena and later human activity is highlighted along the way. It is designed to build your understanding of Earth Science and its relevance to our lives to support your teaching related topics in your classroom. Acknowledgments We would like to thank our partners, the individuals who led the tour to share their expertise, build interest in the natural history of the area, and inspire your teaching. -

Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices For Families Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides the Lower Mainland into 7 zones. Zone 7 identifies affordable housing in the Fraser Valley, Abbotsford and Chilliwack. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies or Co- operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Family Housing, Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford August 2021 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 604-433-2218 or, from outside the Lower Mainland, 1-800-257-7756. You are also welcome to contact The Housing Registry by mail or in person at 101-4555 Kingsway, Burnaby, BC, V5H 4V8. -

THE EVOLUTION of RAILWAYS in the KOOTENAYS by '.• BON ALB

THE EVOLUTION OF RAILWAYS IN THE KOOTENAYS by '.• BON ALB"; HOWARD MEYER' B.A. , Uhiyersity..of British Columbia, 1967 A THESIS .SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS, FOR THE DEGREE OF -MASTER OF ARTS in the Department , " of Geography We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1970 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial, gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8. Canada ABSTRACT « Traditionally, international boundaries have been re• garded as barriers to the evolution of transportation networks. Numerous examples of the disruptive influence of borders on travel routes have been documented in the literature. Does such a pattern always occur? This thesis is concerned with a railnet which evolved in close proximity to an international boundary, but which for the most part appeared able to develop with little regard for the boundary as a barrier. This railnet is that of the Kootenay district of south• eastern British Columbia and the adjacent United States. An investigation is made of the major elements which best explain the nature of this network's evolution. They are discovered to include a rich natural resource endowment, rivalry between rail• way companies, and private and government decision makers, but not the international boundary. -

BC SUMMER GAMES PARTICPANTS Wecommunicate RESPECTFULL

Y BC SUMMER GAMES PARTICPANTS We communicate RESPECTFULL 2018 Nanaimo ▪ Officials: Lisa Balcombe - EGRITY T Nanaimo, Christina Demiris - Vancouver, Sharon Devana – Lake Cowichan, Robyn Guidon – Crofton, Nicola Iten – Anmore, We act with IN ▪ Jennifer Keith – Burnaby, Trish McKay – Vancouver, Anne-Marie North – Burnaby, Deborah Provencher – Nanaimo, Madeleine Ramsay – Merville, Huriye Sefayi – Surrey, Carol Stewart – Victoria, Annie Smith – Burnaby. VE programs I Kootenays (1) INCLUS Head Coach: Erin Fitchett Assistant Coach: Brooke Madore We offer ▪ Athletes: Jessica Cockburn, Kaitlyn Fitchett, Cadence Hergott, Carley Pattyn-Flander, CE Ashley Sonnichsen, Brooke Sonnichsen, Nicole Sonnichsen, N Thompson-Okanagan (2) Head Coach: Elizabeth Ignace Assistant Coach: Carly Helgason We strive We strive for EXCELLE Athletes: Karina Aujla, Maia Cesario, Kierra Fawcett, Rosina Fraser-Bowden, Madison ▪ Gillman, Kate Liebe, Norah Mallett, Isabelle Paradis. NITY U Fraser Valley (3) Head Coach: Madeleine Leblanc Athletes: Abby Yang connected as a COMM We are Suite 3016 – 3713 Kensington Avenue, Burnaby, BC, V5B 0A7 / Tel: (604) 333-3640 Email: [email protected] / Web: www.bcartisticswimming.ca Fraser River Delta (4) Head Coach: Melinda Markser Assistant Coach: Erin Williams Athletes: Nia Draganova, Madison Le, Naomi Madokoro, Zuleida Rodriguez, Elizabeth Tatarnikov, Daisy Vasquez, Kianna Vasquez, Emma West, Kate Zraly. Vancouver-Coastal (5) Head Coach: Alina Aref’yeva Assistant Coach: Seray, Sefayi Athletes: Sophia Alafriz, Rona Dizayee, Eleanor Lee, Alayna Michieli, Ivy Qin, Nyla Statton, Laura Volkamer, Zhang Yameng (Moe). Vancouver Island-Central Coast (6) Head Coach: Brenda Scott Assistant Coach: Samanth Lankmayr Athletes: Anna Akhurst, Maia Bell-McLenana, Avery Dix, Sydney Girling, Kiana Jepson, Pascha Nemlander, Zala Partlow, Sydney Waldie. Cariboo-North East (8) Head Coach: Nicole Barager & Assistant Coach: Lynn Barager Athletes: Camara Glack, Mya Knudsgaard, Sophia Morrow, Sevy Veeken. -

CYMH Intake Clinic Contact Information

CYMH Intake Clinic Contact Information Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, MCFD is committed to providing services to you wherever possible. We can meet you virtually, or by phone so that we can all follow the Provincial Health Officer's direction to ensure physical distancing. Please call the nearest MCFD office to receive information about the services available to you and your family. Region SDA Walk-In Clinic Name Clinic Address Clinic City Clinic Postal Code Clinic Hours Phone Number 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Castlegar 124-845 Columbia Avenue Castlegar V1N 1H3 Wednesday 9:00 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. 250-365-4470 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday 9:30 a.m. UNIT 201 -- 1212 2nd St N 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Cranbrook Cranbrook V1C 4T6 – 12:00 p.m. 250-426-1514 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Creston 224 10th Ave N Creston V0B 1G0 Tuesday 9:00am - 11:00am 250-428-3229 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Fernie 341 2nd Ave Fernie V0B 1M0 Wednesday 1:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m. 250-423-5311 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Golden 1104 9th St S Golden V0A 1H0 Tuesday 9:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. 250-344-7773 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Grand Forks 486B 72nd Avenue Grand Forks V0H 1H0 Thursday 9:00 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. 250-442-4378 1 - Interior SDA 11 - Kootenays CYMH Invermere 625 4 St Invermere Invermere V0A 1K0 Wednesday 9:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. 250-342-4367 CYMH Nakusp (Service First and Third Tuesday 1:00 p.m. -

TDR Vegetation (Pdf)

Technical Data Report Vegetation ENBRIDGE NORTHERN GATEWAY PROJECT AMEC EARTH & ENVIRONMENTAL A division of AMEC Americas Limited Calgary, Alberta David E. Reid, M.Sc., P. Biol. Carol E. Thompson, B.Sc. Mary Ann Johnson, B.Sc., P. Biol. Laura C. Roberts, M.Sc., P. Biol. 2010 Preface This technical data report (TDR) relies primarily on data collected up to September 2008. These data are used in the vegetation environmental and socio-economic assessment (ESA) for the Enbridge Northern Gateway Project, Volume 6A Part 1, Section 8, which also includes more recent data collected up to June 2009. Some minor discrepancies may occur between this TDR and the ESA because of the different datasets. Vegetation Technical Data Report Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Spatial Boundaries ............................................................................................. 1-1 1.1.1 Project Development Area ............................................................................. 1-1 1.1.2 Project Effects Assessment Area .................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Physiographic Regions ....................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Ecosystem Classification .................................................................................... 1-2 2 Methods .......................................................................................................... -

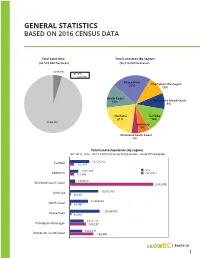

General Statistics Based on 2016 Census Data

GENERAL STATISTICS BASED ON 2016 CENSUS DATA Total Land Area Total Land Area (by region) (92,518,600 hectares) (92,518,600 hectares) 4,615,910 ALR non-ALR Peace River 22% Thompson-Okanagan 10% North Coast 13% Vancouver Island-Coast 9% Nechako Cariboo 21% 14% 87,902,700 Kootenay 6% Mainland-South Coast 4% Total Land & Population (by region) (BC total - Area - 92,518,600 (hectares) & Population - 4,648,055 (people)) Cariboo 13,128,585 156,494 5,772,130 Area Kootenay Population 151,403 3,630,331 Mainland-South Coast 2,832,000 19,202,453 Nechako 38,636 12,424,002 North Coast 55,500 20,249,862 Peace River 68,335 9,419,776 Thompson-Okanagan 546,287 8,423,161 Vancouver Island-Coast 799,400 GROW | bcaitc.ca 1 Total Land in ALR (etare by region) Total Nuber o ar (BC inal Report Number - 4,615,909 hectares) (BC total - 17,528) Cariboo 1,327,423 Cariboo 1,411 Kootenay 381,551 Kootenay 1,157 Mainland-South Coast 161,961 Mainland-South Coast 5,217 Nechako 747 Nechako 373,544 North Coast 116 North Coast 109,187 Peace River 1,335 Peace River 1,333,209 Thompson-Okanagan 4,759 Thompson-Okanagan 808,838 Vancouver Island-Coast 2,786 Vancouver Island-Coast 120,082 As the ALR has inclusions and exclusions throughout the year the total of the regional hectares does not equal the BC total as they were extracted from the ALC database at different times. Total Area o ar (etare) Total Gro ar Reeipt (illion) (BC total - 6,400,549) (BC total - 3,7294) Cariboo 1,160,536 Cariboo 1063 Kootenay 314,142 Kootenay 909 Mainland-South Coast 265,367 Mainland-South Coast 2,4352 -

Late Prehistoric Cultural Horizons on the Canadian Plateau

LATE PREHISTORIC CULTURAL HORIZONS ON THE CANADIAN PLATEAU Department of Archaeology Thomas H. Richards Simon Fraser University Michael K. Rousseau Publication Number 16 1987 Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Roy L. Carlson (Chairman) Knut R. Fladmark Brian Hayden Philip M. Hobler Jack D. Nance Erie Nelson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 0-86491-077-0 PRINTED IN CANADA The Department of Archaeology publishes papers and monographs which relate to its teaching and research interests. Communications concerning publications should be directed to the Chairman of the Publications Committee. © Copyright 1987 Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Late Prehistoric Cultural Horizons on the Canadian Plateau by Thomas H. Richards and Michael K. Rousseau Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Publication Number 16 1987 Burnaby, British Columbia We respectfully dedicate this volume to the memory of CHARLES E. BORDEN (1905-1978) the father of British Columbia archaeology. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................vii List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................iv -

Membership Form

Membership Form HELP US MAKE A DIFFERENCE…. Your membership with CMHA CMHA branches in BC ECOME A EMBER $20 Kootenays includes: B M • Cariboo Chilcotin (Williams Lake) $5 • Cowichan Valley (Duncan) • A voice in the future direction of CMHA • Kamloops $50 Organization* through the opportunity to run for and elect • Kelowna the governing board and attend the Annual • Kootenays (Cranbrook) General Meeting • Mid-Island (Nanaimo) • North and West Vancouver • A subscription to CMHA BC’s free monthly • Port Alberni email newsletter, Mind Matters • Prince George * Memberships expire March 31 2021. • A free subscription to the award-winning • Shuswap-Revelstoke (Salmon Arm) New, non-subsidized memberships that begin quarterly Visions Journal within BC • South Cariboo (100 Mile House) between September 1 and March 31 need • South Okanagan Similkameen (Penticton) only pay half of the regular membership fee. (a $25 value) • Vancouver–Fraser Date • Vernon I would like information on volunteering For contacts and more information, visit our Mr. Ms. Mrs. Dr. I would like information on recognizing website at www.cmha.bc.ca CMHA Kootenays in my will Name In addition to my membership, Address I would like to donate $ City I would like to pay by: Prov. Postal Code _ Cash Cheque Phone ( ) - 100-1000 21st Ave N Cranbrook, BC, V1C 5L9 Mentally healthy people Email Please make cheques payable to phone: 250.426.5222 in a healthy society Canadian Mental Health Association for fax: 250.426.2134 Please do not send mail, including Visions the Kootenays email: [email protected] magazine, unless required by our bylaws www.kootenays.cmha.bc.ca Please do not send e-mail unless required by our bylaws Thank you for your membership as it Charitable registration 13766 1328 RR0001 I am under the age of 19, or an employee will assist in obtaining grants and of the CMHA Kootenays and am a non- additional funding to support our local 2020 voting member programming. -

British Columbia Coast Birdwatch the Newsletter of the BC Coastal Waterbird and Beached Bird Surveys

British Columbia Coast BirdWatch The Newsletter of the BC Coastal Waterbird and Beached Bird Surveys Volume 6 • November 2013 COASTAL WATERBIRD DATA SUPPORTS THE IMPORTANT BIRD AREA NETWORK by Krista Englund and Karen Barry Approximately 60% of British Columbia’s BCCWS data was also recently used to 84 Important Bird Areas (IBA) are located update the English Bay-Burrard Inlet and along the coast. Not surprisingly, many Fraser River Estuary IBA site summaries. BC Coastal Waterbird Survey (BCCWS) Both sites have extensive coastline areas, IN THIS ISSUE sites are located within IBAs. Through the with approximately 40 individual BCCWS • Coastal Waterbird survey, citizen scientists are contributing sites in English Bay Burrard Inlet and 22 Survey Results valuable data to help refine boundaries of in the Fraser River Estuary, although not • Beached Bird IBAs, update online site summaries (www. all sites are surveyed regularly. BCCWS Survey Results ibacanada.ca), and demonstrate that data helped demonstrate the importance • Common Loons these areas continue to support globally of English Bay-Burrard Inlet to Surf • Triangle Island significant numbers of birds. Scoters and Barrow’s Goldeneyes. In the • Forage Fish Fraser River Estuary, BCCWS data was • Tsunami Debris One recent update involved amalgamating particularly useful for demonstrating use • Real Estate three Important Bird Areas near Comox on of this IBA by globally significant numbers Foundation Project Vancouver Island into a single IBA called of Thayer’s Gull, Red-necked Grebe and • Web Resources K’omoks. BCCWS data from up to 52 survey Western Grebe. sites on Vancouver Island, Hornby and Denman Islands helped to identify areas BCCWS surveyors have made great of high bird use and provide rationale contributions to the BC Important Bird for the new boundary, which extends Areas program and we thank all past and from approximately Kitty Coleman Beach present volunteers. -

Agricultural Economy in the Fraser Valley Regional District TABLE of CONTENTS

Image courtesy Chilliwack Economic Partners Corp Regional Snapshot Series: Agriculture Agricultural Economy in the Fraser Valley Regional District TABLE OF CONTENTS A Region Defined by Agriculture Competitive Advantage Economics of Agriculture: A National Perspective Economics of Agriculture: Provincial Context Economics of Agriculture: Regional Context Agricultural Land Reserve Agricultural Diversity Agriculture Challenges Agriculture Opportunities Regional Food Security The Fraser Valley Regional District is comprised of 6 member municipalities and 7 electoral areas. City of Abbotsford, City of Chilliwack, District of Mission, District of Hope, District of Kent, Village of Harrison Hot Springs and Electoral Areas A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Fraser Valley Regional District In partnership with: A NOTE ON CENSUS DATA LIMITATIONS Although every effort has been made in the preparation of the Regional Snapshot Series to present the most up-to-date information, the most recent available Census data is from 2006. The most recent Census of Agriculture took place in May of 2011, however results will not be available until mid-2012. The snapshot will be updated to reflect the 2011 Census of Agriculture results. A REGION DEFINED BY AGRICULTURE CHOICES FOR TODAY AND INTO THE FUTURE OUR FUTURE: Agriculture: A 21st century industry The Fraser Valley Regional District (FVRD) is comprised of six member municipalities our Regional and seven electoral areas and features a variety of diverse communities, from small rural hamlets to the fifth largest city in British Columbia. The FVRD is one of the most Growth Strategy intensively farmed areas in Canada, generating the largest annual farm receipts of any regional district in British Columbia.