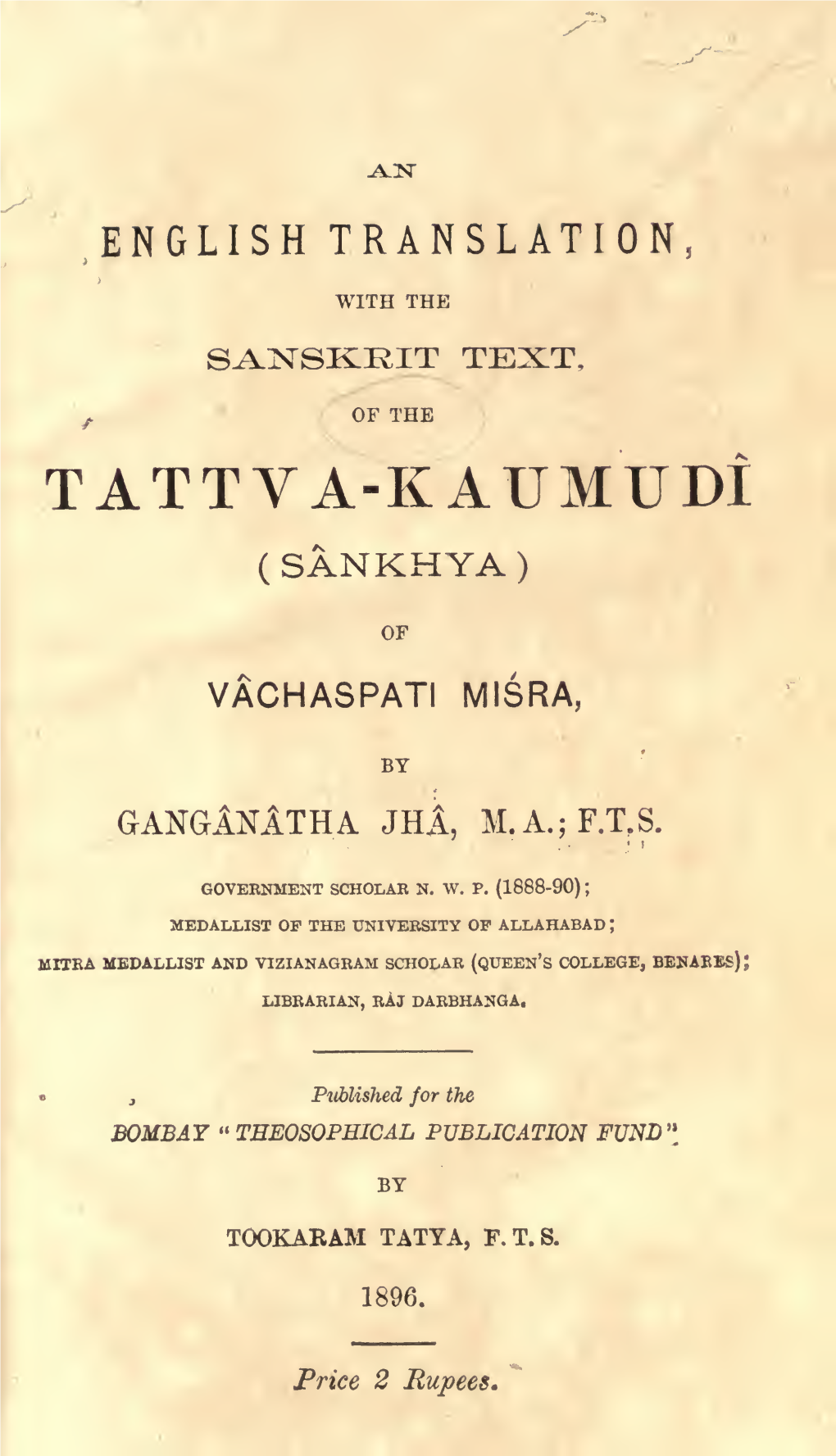

Sankhya Karika Tattuva Kaumudi of Vachaspati Misra Ganganatha Jha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus Asia Subscribe for Free Direct to Your Inbox Every Week Anzbloodstocknews.Com/Asia

FOCUS ASIA SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX EVERY WEEK ANZBLOODSTOCKNEWS.COM/ASIA Wednesday, June 9, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here STEVE MORAN - PAGE 13 FOCUS ASIA - PAGE 11 Valuable mare Tofane Read Tomorrow's Issue For It's In The Blood could still be on the market What's on Winter carnival to determine whether daughter of Ocean Park Metropolitan meetings: Canterbury races on next season (NSW), Belmont (WA) Race Meetings: Sale (VIC), Sunshine Coast (QLD), Strathalbyn (SA), Matamata (NZ) Barrier trials / Jump-outs: Kembla Grange (NSW), Pakenham (VIC), Mornington (VIC), Wangaratta (VIC) International meetings: Happy Valley (HK), Hamilton (UK), Haydock (UK), Kempton (UK), Yarmouth (UK), Cork (IRE), Lyon (FR) Sales: Inglis Digital June (Early) Sale International Sales: OBS June 2YOs and Horses of Racing Age (USA) Toofane RACING PHOTOS Coast auction last month, ran on well to finish BY TIM ROWE | @ANZ_NEWS runner-up to Emerald Kingdom (Bryannbo’s MORNING BRIEFING tradbroke Handicap (Gr 1, 1400m) Gift) in the BRC Sprint (Gr 3, 1350m) on May contender Tofane (Ocean Park), 22, a performance that convinced her owners Oaks winner Personal to whose racetrack career was extended to race her on during the Queensland winter race in the US after connections gave up a gilt- carnival. VRC Oaks (Gr 1, 2500m) winner Personal (Fastnet Sedged opportunity to sell the valuable mare at “There’s no doubt that she was highly sought Rock) is moving to the US to be trained in New the Magic Millions National Broodmare Sale, after. We had a lot of enquiry for her leading into York by Chad Brown. -

Professor Alex Wayman

RESEARC.HES JN Essays in Honour of Professor Alex Wayman Edited by RAM KARAN SHARMA MOTILAL nANARSIDASS PUnLlSHERS PR(VATE LIMITED .DELHI Firsl Edilion: Delhi, 1993 C MOTILAL HANARSIDASS PUBLlSHERS PRIVATE LrMITED AII Rights R.:servcd ISBN: 81-208-0994-7 Also avail"hle at; MOTILAL BANARSIDASS 41 U.A., Bungalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Delhi 110007 120 Royapettah High Road, Mylapore, Madras 600004 16 Sto Mark's Road, Bangalore 560001 Ashok Rajpath, Patna 800 004 Chowk, Varanasi 221001 PRINTFD IN INDIA BY JAINI!NDRA PRAKASH JAIN AT SURI JAINE='OORA PREs.". A-45 NARAlNA NDUSTRIAL ARI!A, PHASI! 1, NEW DELHI 110028 AND PUBLISIIED BY NARI!NDRA PRAKASH JAI:-¡ FOR MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PRIVATI! LIMn"BD, BUNOALOW ROA/), JAWAHAR NAOAR, DELHI 110007 ~ f CONTENTS Pr(fclC(' VII Em('ll('ou'.1" B/c.l"l"ill.I;'.1" XI Biilgrtlphicll/ Skc!ch nl,41I'.\" IVIZI'lllIlI/ xiii Bib/iograph.l' xxiii BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHICAL RESEARCHES A. ~1ISCELLANEOUS l. The List of th\: A.\"U1]lSkrtú-tlharmaAccording to Asaóga A1':DRÉ BAREAU 2. The ~ven PrincipIes of thc Vajjian Republic: Thcir Differl;nt Interpretation:) HAJIME NAKAMURA 7 3. A Difficult Beginning: Comments on an English Translation of C.mdragomin's Desandstava MICHAEL HAHN 31 4. A Study of Aspects of Rága N. H. SAMTANI 61 B. KARMA THEORY 5. PrincipIe of Life According to Bhavya SHINJO KAWASAKI 69 6. TJle Buddhist Doctrine of Karma HARI SHANKAR PRASAD 83 7. A Critical Appraisal of Karmaphalaparik~aof Nagarjuna T. R. SHARMA 97 C. DEPENDENT ORIGINATION 8. Thc Rclationship bctweenPatíccasamllppüda and Dhóttl AKIRA lfIRAKAWA 105 9. -

Shamus Tops the Charts As Duais Lands Stallion a Third Elite Level Winner of Season | 2 | Sunday, June 6, 2021

Sunday, June 6, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here SECOND STAKES WINNER FOR ASTERN - PAGE 10 MORNING BRIEFING - PAGE 7 Shamus tops the charts as What's on Duais lands stallion a third Metropolitan meetings: Devonport (TAS) Race meetings: Murwillumbah (NSW), elite level winner of season Muswellbrook (NSW), Bairnsdale (VIC), Edward becomes the latest Cummings to add Group 1 training Geelong (VIC), Ipswich (QLD), Pinjarra Park (WA), Roebourne (WA), Port Augusta (SA), win from illustrious racing family with Queensland Oaks victory Wingatui (NZ) Barrier trials / Jump-outs: Murwillumbah (NSW) International meetings: Sha Tin (HK), Tokyo (JPN), Chukyo (JPN), Goodwood (UK), Listowel (IRE), Chantilly (FR), Mulheim (GER) International Group races: Tokyo (JPN) - Yasuda Kinen (Gr 1, 1600m). Chantilly (FR) - Prix du Jockey Club (Gr 1, 2100m), Prix de Sandringham (Gr 2, 1600m), Prix du Gros-Chene (Gr 2, 1000m), Grand Prix de Chantilly (Gr 2, 2400m), Prix de Royaumont (Gr 3, 2400m). Mulheim (GER) - Grosser Preis der rp Gruppe (Gr 2, 2200m) Duais MICHAEL MCINALLY Sales: Inglis Digital June (Early) Sale Group 1 winners for the campaign, ahead of a host BY ALEX WILTSHIRE | @ANZ_NEWS of leading sires on two, including Snitzel, Fastnet osemont Stud’s Shamus Award Rock (Danehill), Exceed And Excel (Danehill), (Snitzel) moved to the top of the Frankel (Galileo), All Too Hard (Casino Prince) Group 1-winning sire charts for and Savabeel (Zabeel). the 2020/21 season after siring Duais became Shamus Award’s second Rhis third Group 1 winner this term courtesy of individual Oaks winner for the season, following yesterday’s Queensland Oaks (Gr 1, 2200m) on from Media Award’s win in the Australasian winner Duais (3 f Shamus Award - Meerlust by Oaks (Gr 1, 2000m) last month, a feat only Johannesburg). -

Aesthetic Philosophy of Abhina V Agupt A

AESTHETIC PHILOSOPHY OF ABHINA V AGUPT A Dr. Kailash Pati Mishra Department o f Philosophy & Religion Bañaras Hindu University Varanasi-5 2006 Kala Prakashan Varanasi All Rights Reserved By the Author First Edition 2006 ISBN: 81-87566-91-1 Price : Rs. 400.00 Published by Kala Prakashan B. 33/33-A, New Saket Colony, B.H.U., Varanasi-221005 Composing by M/s. Sarita Computers, D. 56/48-A, Aurangabad, Varanasi. To my teacher Prof. Kamalakar Mishra Preface It can not be said categorically that Abhinavagupta propounded his aesthetic theories to support or to prove his Tantric philosophy but it can be said definitely that he expounded his aesthetic philoso phy in light of his Tantric philosophy. Tantrism is non-dualistic as it holds the existence of one Reality, the Consciousness. This one Reality, the consciousness, is manifesting itself in the various forms of knower and known. According to Tantrism the whole world of manifestation is manifesting out of itself (consciousness) and is mainfesting in itself. The whole process of creation and dissolution occurs within the nature of consciousness. In the same way he has propounded Rasadvaita Darsana, the Non-dualistic Philosophy of Aesthetics. The Rasa, the aesthetic experience, lies in the conscious ness, is experienced by the consciousness and in a way it itself is experiencing state of consciousness: As in Tantric metaphysics, one Tattva, Siva, manifests itself in the forms of other tattvas, so the one Rasa, the Santa rasa, assumes the forms of other rasas and finally dissolves in itself. Tantrism is Absolute idealism in its world-view and epistemology. -

Our Broodmare Report Analyses up to 250 Stallions

SALES NEWS - PAGE 18 ‘CHAIRMAN’S QUALITY’ MARES TO GO UNDER THE HAMMER AT AUSTRALIAN BROODMARE SALE Sunday, May 9, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here EXPLOSIVE JACK CONTINUES DERBY BLITZ AND MAKES HISTORY AT MORPHETTVILLE - PAGE 1 Our Broodmare Report analyses up to 250 Stallions A detailed report identifying the top 40 stallions (out of 250) for your broodmare based on a set of criteria determined by you. Each report includes: • G1 Goldmine Rating • Impact Profile: highlight positive & negative crosses within a pedigree • Aptitude Profile: Visually see past stakes success for Age & Distance • Stallion Match: Duplicate proven pedigrees To order visit www.g1goldmine.com SALES NEWS - PAGE 18 ‘CHAIRMAN’S QUALITY’ MARES TO GO UNDER THE HAMMER AT AUSTRALIAN BROODMARE SALE Sunday, May 9, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here STALLION FEES ROSTER - PAGE 27 FIRST SEASON SIRE RUNNERS - PAGE 55 Explosive Jack continues Read Tomorrow's Issue For The Week Ahead Derby blitz and makes What's on Metropolitan meetings: Devonport (TAS) history at Morphettville Race meetings: Goulburn (NSW), Mudgee (NSW), Ballarat (VIC), Sunshine Coast Maher and Eustace colt adds South Australian Derby to his (QLD), Kalgoorlie (WA), Woodville (NZ) Tasmanian and ATC victories Barrier trials / Jump-outs: Goulburn (NSW), Mudgee (NSW), Kalgoorlie (WA) International meetings: Tokyo (JPN), Chukyo (JPN), Niigata (JPN), Kranji (SGP), Taipa (MAC), Scottsville (SAF), Leopardstown (IRE), Killarney (IRE) International Group races: Tokyo (JPN) - NHK Mile Cup (Gr 1, 1600m). Niigata (JPN) - Niigata Daishoten (Gr 3, 2000m). Scottsville (SAF) - Strelitzia Stakes (Gr 3, 1100m), Barb Stakes (Gr 3, 1100m), Poinsettia Stakes (Gr 3, 1200m). -

This Sheela Looks Smokin'

www.turftalk.co.za / [email protected] Friday 4 June, 2021 This Sheela looks smokin’ hot Visitors to Australia and New Zealand will hear locals using the word “Sheila”. Expressions such as “Just look at that Sheila” and “Blimey, that Sheila is hot” are commonplace. It’s a slang name for a girl or young woman, writes David Mollett. There is a female with a similar name running If there is one worry about Sheela, it’s that the at Hollywoodbets Scottsville on Sunday filly she beat on her second start, Social Media, (rescheduled from Saturday due to heavy rain) failed to boost the form in her next two starts. but with a slightly different spelling — Sheela. Another highveld-trained filly with a 100% Punters are hoping she will prove hot in the record is Sean Tarry’s Sound Of Warning and grade 1 Allan Robertson Memorial and the she’s bred in the purple being out of the Mike and Adam Azzie inmate goes to post with talented race mare Siren Call. two impressive wins to her credit. It’s in her favour that she has won on the She has provided an immediate boost for her Scottsville track which has been the downfall of sire, The United States, a seven-time winning a number of fancied runners in the past. son of Galileo. (to Page 2) 1 This Sheela looks smoking’ hot—from Page 1 She won the Strelitzia Stakes and the boxed Glen Kotzen has his team in good form and exacta with Sheela could prove the best way to Good Traveller bids to make it four wins in a bet. -

Theosophical Review V39 N232 Dec 1906

THE TH EOSOPH ICAL REVIEW Vol. XXXIX DECEMBER, 19o6 No. 232 ON THE WATCH-TOWER " " The article on The Master which appeared in our last number may perhaps have served to remind some of our readers of the nature of one of the fundamental con- " " TS^ddha°f ceptions of the christology of Buddhism according to the Great Vehicle or Mahayana School. Those who are interested in the subject of the Trikaya, or Three Modes of Activity, generally called the Three Bodies, of the Buddha —and what real student of Theosophy can fail to be interested ? —will be glad to learn that an excellent resume of the manifold views of the Buddhist doctors, and of the labours of Occidental scholars on this mysterious tenet has just appeared in The Journal of the - Royal Asiatic Society, from the pen of " M. Louis de la Valine Poussin, entitled : Studies in Buddhist Dogma : The Three Bodies of a Buddha (Trikaya)." This sym pathetic scholar of Buddhism, —who has done so much to restore the balance of Buddhistic studies, by insisting on the importance of the Mahayana tradition in face of the one-sidedness of the Paliists who would find the orthodoxy of Buddhism in the 2g0 THE THEOSOPHICAL REVIEW Hinayana, or School of the Little Vehicle, alone, — says that the Trikaya teaching was at first a "buddhology," or speculative doctrine of the Buddhahood alone, which was subsequently made to cover the whole field of dogmatics and ontology. This may very well be so if we insist on regarding the subject solely from the standpoint of the history of the evolution of dogma; but since, as M. -

Programa Com Retrospecto Da 2.807ª Corrida

ASCOT Sábado -19 de junho de 2021 PROGRAMA COM RETROSPECTO DA 2.807ª CORRIDA 1º Páreo 10:30 - BR CHESHAM STAKES - 2021 Galope 1400 M Bolsa: €75.968 1 GREAT MAX 58,5 JAMES DOYLE 5 MICHAEL BELL 1p 2 MASEKELA 58,5 OISIN MURPHY 1 ANDREW BALDING 1p 3 NEW SCIENCE 58,5 WILLIAM BUICK 4 CHARLIE APPLEBY 1p 4 POINT LONSDALE 58,5 RYAN MOORE 7 AIDAN O'BRIEN 1p 5 REACH FOR THE MOON 58,5 FRANKIE DETTORI2 JOHN & THADY GOSDEN 2p 6 SHARP COMBO 58,5 FRANNY NORTON8 MARK JOHNSTON 1p5p 7 SWEEPING 58,5 HOLLIE DOYLE 6 ARCHIE WATSON 2p 8 WITHERING 58,5 DAVID EGAN 3 JAMIE OSBORNE 2p 9 OUT IN YORKSHIRE 56 BEN CURTIS 9 MARK JOHNSTON 2p1p 10 RADIO CAROLINE 56 CHARLES BISHOP10 MICK CHANNON 1p7p GREAT MAX WOOTTON BASSETT e TEESLEMEE(YOUMZAIN) - MICHAEL BELL - M - - 2 ANOS 1 JAMES DOYLE 58,5 AMO RACING LIMITED 10/06/21 01º(11) 11 JACK MITCHELL 58 1.250 01'19''49 CONDITIONS RACE HARROW(58)/GAIUS(58) NEWBURY 7.591 MASEKELA EL KABEIR e LADY'S PURSE(DOYEN) - ANDREW BALDING - M - - 2 ANOS 2 OISIN MURPHY 58,5 MICK AND JANICE MARISCOTTI 21/05/21 01º(6) 06 OISIN MURPHY 59,5 1.200 01'16''69 CONDITIONS RACE GOLDEN WAR(59,5)/FALL OF ROME(59,5) GOODWOOD 9.902 NEW SCIENCE LOPE DE VEGA e ALTA LILEA(GALILEO) - CHARLIE APPLEBY - M - - 2 ANOS 3 WILLIAM BUICK 58,5 GODOLPHIN 28/05/21 01º(12) 09 WILLIAM BUICK 59,5 1.400 01'29''74 CONDITIONS RACE REACH FOR THE MOON(59,5)/PAPA COCKTAIL(59,5) YARMOUTH 6.381 POINT LONSDALE AUSTRALIA e SWEEPSTAKE(ACCLAMATION) - AIDAN O'BRIEN - M - - 2 ANOS 4 RYAN MOORE 58,5 D.SMITH,MRS J.MAGNIER,M.TABOR,WE 02/06/21 01º(11) J.A. -

The Essence of the Samkhya II Megumu Honda

The Essence of the Samkhya II Megumu Honda (THE THIRD CHAPTER) (The opponent questions;) Now what are the primordial Matter and others, from which the soul should be discriminated? (The author) replies; They are the primordial Matter (prakrti), the Intellect (buddhi), the Ego- tizing organ (ahankara), the subtle Elements (tanmatra), the eleven sense organs (indriya) and the gross Elements (bhuta) in sum just 24." The quality (guna), the action (karman) and the generality (samanya) are included in them because a property and one who has property are iden- tical (dharma-dharmy-abhedena). Here to be the primordial Matter means di- rectly (or) indirectly to be the material cause (upadanatva) of all the mo- dification (vikara), because its chief work (prakrsta krtih) is formed of tra- nsf ormation (parinama), -thus is the etymology (of prakrti). The primordial Matter (prakrti), the Capacity (sakti), the Unborn (aja), the Principal (pra- dhana), the Unevolved (avyakta), the Dark (tamers), the Illusion (maya), the Ignorance (avidya) and so on are the synonyms') of the primordial Matter. For the traditional scripture says; "Brahmi (the Speech) means the science (vidya) and the Ignorace (avidya) means illusion (maya) -said the other. (It is) the primordial Matter and the Highest told the great sages2)." And here the satt va and other three substances are implied (upalaksita) as. the state of equipoise (samyavastha)3). (The mention is) limitted to implication 1) brahma avyakta bahudhatmakam mayeti paryayah (Math. ad SK. 22), prakrtih pradhanam brahma avyaktam bahudhanakammayeti paryayah (Gaudap. ad SK. 22), 自 性 者 或 名 勝 因 或 名 爲 梵 或 名 衆 持(金 七 十 論ad. -

Nottingham Racecourse - 14/10/2020

NOTTINGHAM RACECOURSE - 14/10/2020 Race 1 1.00 1m 75y Race 2 1.30 1m 75y Race 3 2.00 1m 75y THE EBF THE EBF MAIDEN FILLIES’ THE WATCH AND BET AT MAIDEN STAKES STAKES (CLASS 5) MANSIONBET NURSERY (CLASS 5) (PLUS 10/GBB RACE) HANDICAP STAKES (CLASS 5) 1 Adayar (IRE) 2 9-5 (1) 1 Horsefly (IRE) 0 2 9-0 (9) 1 Luxy Lou (IRE) 043 2 9-9 (11) B c Frankel - Anna Salai (USA) (Dubawi (IRE)) B f Camelot - Forthefirstime (Dr Fong (USA)) Ch f The Last Lion (IRE) - Dutch Courage Godolphin Mrs G Rowland-Clark & Partner (Dutch Art) Charlie Appleby William Buick Michael Bell Kieran Shoemark Merriebelle Ltd, Sullivan Bloodstock Ltd Richard Hannon Sean Levey 2 Carpentier (FR) 600 2 9-5 (7) 2 Kalma 00 2 9-0 (5) B g Intello (GER) - Ellary (FR) (Equerry (USA)) B f Mukhadram - Peters Spirit (IRE) 2 Mark of Respect (IRE) 104 2 9-8 (6) Middleham Park Racing XLV (Invincible Spirit (IRE)) B c Markaz (IRE) - Music Pearl (IRE) Sir Mark Prescott Bt Ryan Tate Elysees Partnership (Oratorio (IRE)) Alan King Hector Crouch Berkeley Racing 3 Encounter Order (IRE) 62 2 9-5 (11) Jonathan Portman Ben Curtis B c Siyouni (FR) - Miss Emma May (IRE) 3 Missile 2 9-0 (1) (Hawk Wing (USA)) B f Dubawi (IRE) - Ribbons 3 Mind That Jet (IRE) 056,T 2 9-8 (9) Mr Abdulla Al Mansoori (Manduro (GER)) B g Kodiac - Rate (Galileo (IRE)) Ismail Mohammed Ryan Moore Westerberg Davood Vakilgilani John Gosden Frankie Dettori Mohamed Moubarak Hector Crouch 4 Graystone (IRE) 30 2 9-5 (9) Gr or Ro c Dark Angel (IRE) - Crown of Diamonds (USA) 4 Mrs Fitzherbert (IRE) 2 9-0 (6) 4 Parish Academy (IRE) 023,H 2 9-8 (15) (Distorted Humor (USA)) B f Kingman - Stupendous Miss (USA) B c Parish Hall (IRE) - Royal Bean (USA) Pia and James Summers (Dynaformer (USA)) (Royal Academy (USA)) Lucy Wadham Paul Hanagan Sonia M. -

Acrobat Bounces Back from Life-Threatening Illness to Target Coolmore Stud Stakes | 2 | Thursday, June 10, 2021

ARGENTIA - PAGE 17 Thursday, June 10, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here TBA FAST TRACK STUDENTS GRADUATE - PAGE 16 HONG KONG NEWS - PAGE 19 Acrobat bounces back from Read Tomorrow's Issue For life-threatening illness to Maiden of the Week target Coolmore Stud Stakes What's on Race meetings: Gosford (NSW), Ballarat Exciting Fastnet Rock colt on way to Melbourne to start spring (VIC), Pinjarra (AUS), Rockhampton (QLD), preparation with Maher and Eustace New Plymouth (NZ) International race meetings: Haydock (UK), Newbury (UK), Nottingham (UK), Yarmouth (UK), Leopardstown (IRE), ParisLongchamp (FR), International Sales: OBS June 2YOs and Horses of Racing Age (USA) SALES NEWS Member’s Joy sells for Acrobat SPORTPIX $800,000 to shine bright Inglis Millennium (RL, 1200m) raceday at on Inglis Digital BY TIM ROWE | @ANZ_NEWS Randwick, Acrobat suffered a cut to his left Segenhoe Stud are revelling in an inspired crobat (Fastnet Rock), a one- hock while on the walker at trainers Ciaron decision to have stakes-producing time Golden Slipper Stakes (Gr 1, Maher and David Eustace’s Warwick Farm broodmare Members Joy (Hussonet) act as 1200m) favourite and this season’s stables. the shining protagonist in the June (Early) forgotten juvenile, will be given Initially, the injury was not thought to Inglis Digital Sale, as the mare smashed the Athe chance to make up for lost time as a three- be serious and plans were still being made previous Inglis Digital record, and became year-old after winning a remarkable life-and- for the Inglis Nursery (RL, 1000m) winner to the most expensive mare in foal to sell online death battle with illness. -

TAILORMADE PEDIGREE for HURRICANE LANE (IRE)

TAILORMADE PEDIGREE for HURRICANE LANE (IRE) Galileo (IRE) Sadler's Wells (USA) Sire: (Bay 1998) Urban Sea (USA) FRANKEL (GB) (Bay 2008) Kind (IRE) Danehill (USA) HURRICANE LANE (IRE) (Bay 2001) Rainbow Lake (GB) (Chesnut colt 2018) Shirocco (GER) Monsun (GER) Dam: (Bay 2001) So Sedulous (USA) GALE FORCE (GB) (Bay 2011) Hannda (IRE) Dr Devious (IRE) (Chesnut 2002) Handaza (IRE) 4Sx5Sx5Dx6Dx5D Northern Dancer, 5Sx6Sx6Dx6D Nearctic, 5Sx6Sx6Sx6Dx6D Natalma, 6Sx6S Buckpasser Last 5 starts 26/06/2021 1st DUBAI DUTY FREE IRISH DERBY (Group 1) Curragh 12f £508,929 STAKES 05/06/2021 3rd THE CAZOO DERBY (Class 1) (Group 1) (British Epsom Downs 12f 6y £121,050 Champions Series) 13/05/2021 1st THE AL BASTI EQUIWORLD DUBAI DANTE York 10f 56y £93,572 STAKES (CLASS 1) (Group 2) 16/04/2021 1st THE DUBAI DUTY FREE GOLF WORLD CUP Newbury 10f £8,370 BRITISH EBF CONDITIONS STAKES (CLASS 3) (PLUS 10 RACE) 21/10/2020 1st THE BRITISH EBF FUTURE STAYERS NOVICE Newmarket 8f £10,350 STAKES (CLASS 2) (Sire/Dam-Restricted Race) (PLUS 10 RACE) HURRICANE LANE (IRE), 200,000 gns. yearling Tattersalls October Yearling Sale (Book 1) 2019 - Godolphin, (120), won 4 races (8f.-12f.) at 2 and 3 years, 2021 and £742,271 including Irish Derby, Curragh, Gr.1 and Dante Stakes, York, Gr.2, placed third in Derby Stakes, Epsom Downs, Gr.1, (Charlie Appleby), all his starts; own brother to Frankel's Storm (GB). 1st Dam GALE FORCE (GB) (2011 f. by Shirocco (GER)), 15,000 gns. yearling Tattersalls October Yearlings Sale (Book 2) - Vendor, 270,000 gns.