New Light on the Cahow, Pterodroma Cahow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bermuda Biodiversity Country Study - Iii – ______

Bermuda Biodiversity Country Study - iii – ___________________________________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Island’s principal industries and trends are briefly described. This document provides an overview of the status of • Statistics addressing the socio-economic situation Bermuda’s biota, identifies the most critical issues including income, employment and issues of racial facing the conservation of the Island’s biodiversity and equity are provided along with a description of attempts to place these in the context of the social and Government policies to address these issues and the economic needs of our highly sophisticated and densely Island’s health services. populated island community. It is intended that this document provide the framework for discussion, A major portion of this document describes the current establish a baseline and identify issues requiring status of Bermuda’s biodiversity placing it in the bio- resolution in the creation of a Biodiversity Strategy and geographical context, and describing the Island’s Action Plan for Bermuda. diversity of habitats along with their current status and key threats. Particular focus is given to the Island’s As human use or intrusion into natural habitats drives endemic species. the primary issues relating to biodiversity conservation, societal factors are described to provide context for • The combined effects of Bermuda’s isolation, analysis. climate, geological evolution and proximity to the Gulf Stream on the development of a uniquely • The Island’s human population demographics, Bermudian biological assemblage are reviewed. cultural origin and system of governance are described highlighting the fact that, with 1,145 • The effect of sea level change in shaping the pre- people per km2, Bermuda is one of the most colonial biota of Bermuda along with the impact of densely populated islands in the world. -

Letter from the Desk of David Challinor August 2001 About 1,000

Letter From the Desk of David Challinor August 2001 About 1,000 miles west of the mid-Atlantic Ridge at latitude 32°20' north (roughly Charleston, SC), lies a small, isolated archipelago some 600 miles off the US coast. Bermuda is the only portion of a large, relatively shallow area or bank that reaches the surface. This bank intrudes into the much deeper Northwestern Atlantic Basin, an oceanic depression averaging some 6,000 m deep. A few kilometers off Bermuda's south shore, the depth of the ocean slopes precipitously to several hundred meters. Bermuda's geographic isolation has caused many endemic plants to evolve independently from their close relatives on the US mainland. This month's letter will continue the theme of last month's about Iceland and will illustrate the joys and rewards of longevity that enable us to witness what appears to be the beginnings of landscape changes. In the case of Bermuda, I have watched for more than 40 years a scientist trying to encourage an endemic tree's resistance to an introduced pathogen. My first Bermuda visit was in the spring of 1931. At that time the archipelago was covered with Bermuda cedar ( Juniperus bermudiana ). This endemic species was extraordinarily well adapted to the limestone soil and sank its roots deep into crevices of the atoll's coral rock foundation. The juniper's relatively low height, (it grows only 50' high in sheltered locations), protected it from "blow down," a frequent risk to trees in this hurricane-prone area. Juniper regenerated easily and its wood was used in construction, furniture, and for centuries in local boat building. -

Molecular Ecology of Petrels

M o le c u la r e c o lo g y o f p e tr e ls (P te r o d r o m a sp p .) fr o m th e In d ia n O c e a n a n d N E A tla n tic , a n d im p lic a tio n s fo r th e ir c o n se r v a tio n m a n a g e m e n t. R u th M a rg a re t B ro w n A th e sis p re se n te d fo r th e d e g re e o f D o c to r o f P h ilo so p h y . S c h o o l o f B io lo g ic a l a n d C h e m ic a l S c ie n c e s, Q u e e n M a ry , U n iv e rsity o f L o n d o n . a n d In stitu te o f Z o o lo g y , Z o o lo g ic a l S o c ie ty o f L o n d o n . A u g u st 2 0 0 8 Statement of Originality I certify that this thesis, and the research to which it refers, are the product of my own work, and that any ideas or quotations from the work of other people, published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard referencing practices of the discipline. -

Conservation Action Plan Black-Capped Petrel

January 2012 Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata) Edited by James Goetz, Jessica Hardesty-Norris and Jennifer Wheeler Contact Information for Editors: James Goetz Cornell Lab of Ornithology Cornell University Ithaca, New York, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Jessica Hardesty-Norris American Bird Conservancy The Plains, Virginia, USA E-mail: [email protected] Jennifer Wheeler U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arlington, Virginia, USA E-mail: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Goetz, J.E., J. H. Norris, and J.A. Wheeler. 2011. Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata). International Black-capped Petrel Conservation Group http://www.fws.gov/birds/waterbirds/petrel Funding for the production of this document was provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Table Of Contents Introduction . 1 Status Assessment . 3 Taxonomy ........................................................... 3 Population Size And Distribution .......................................... 3 Physical Description And Natural History ................................... 4 Species Functions And Values ............................................. 5 Conservation And Legal Status ............................................ 6 Threats Assessment ..................................................... 6 Current Management Actions ............................................ 8 Accounts For Range States With Known Or Potential Breeding Populations . 9 Account For At-Sea (Foraging) Range .................................... -

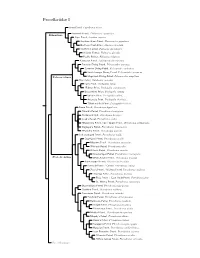

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

A Black-Capped Petrel Specimen from Florida the Black-Capped Petrel (Pterodroma Hasitata) Is a Rare Bird Anywhere in North America (Palmer, 1962)

Florida Field Naturalist Vol. 2 Spring 1974 gulls circled with the downwind passage about 2 t,o 4 meters over our heads. When we tossed a fish into the path of one, it caught the fish easily, often performing int,ricate aerial maneuvers to do so. We counted only 12 misses in 97 tosses in which we judged t,he adult should have caught the fish. The juvenile, on the other hand, hovered out of the mainstream of the flock approximately 10 to 13 meters above and to one side of us. It called frequently, behavior rarely exhibited by the adults, and whenever we t,hrew a fish in its direct,ion, it attempted to avoid rather than catch it. It ap- peared to be curious about the other gulls' activity but seemed unaware of how to become involved and what to do, After several minut,es of hovering nearby, t,he young bird joined the flight pattern of the adults but remained about 4 to 9 meters over our heads. We attempted to direct fish toward this young individual and in circumstances similar t,o those of the adult the juvenile caught only one of 23 fish. In four of these cases an adult stole the fish before t,he young could respond. The one fish the young captured was the last one thrown, approxin~at,elyten minutes after it joined the flock. Wat,ching this bird, it was obvious to us that at first it was attracted to the flock of gulls, and only after a period of time did it realize that food was available. -

Hatteras Black-Capped Petrel Planning Meeting Hatteras, North Carolina June 16 and 17, 2009 – Meeting Days

HATTERAS BLACK-CAPPED PETREL PLANNING MEETING HATTERAS, NORTH CAROLINA JUNE 16 AND 17, 2009 – MEETING DAYS. JUNE 18, 2009 – ON BOAT Attendees, current affiliation Chris Haney, Defenders of Wildlife, [email protected] Kate Sutherland, Seabirding Pelagic Trips, [email protected] Jennifer Wheeler, USFWS, [email protected] Brian Patteson, Seabirding Pelagic Trips, [email protected] Stefani Melvin, USFWS, [email protected] Dave Lee, Tortoise Reserve, [email protected] Ted Simons, North Carolina State University, [email protected] Jessica Hardesty, American Bird Conservancy, [email protected] Marcel Van Tuinen, University of North Carolina, [email protected] Will Mackin, Jadora (and wicbirds.net), [email protected] David Wingate, Cahow Project, retired, [email protected] Elena Babij, USFWS, [email protected] Wayne Irvin, photographer, retired, [email protected] Britta Muiznieks, National Park Service, [email protected] Discussions: David Wingate – Provided a overview of the Cahow (Bermuda Petrel) including the history, lessons learned, and management actions undertaken for the petrel. The importance of working with all stakeholders to conserve a species was stressed. One key item was that there must be more BCPEs than we know as so many seen at sea! Do a rough ratio of Cahow sightings to known population; could also use sightings of BCPE to estimate abundance. Ted Simons: Petrel Background: A number of species have been lost to science. He focused on the Hawaiian/Dark-rumped Petrel (lost and re-discovered). Points covered: • Probably occurred at all elevations • Now scattered, in isolated locations (not really colonial – 30 m to 130 m apart) • Intense research – metabolic, physiologic characteristics of adults, chicks and eggs; pattern of adult tending and feeding, diet and stomach oil • Management: fencing herbivores out (fences are source of mortality) • Estimated life history and stable age distribution; clues on where to focus management • K-selected: Reduce adult mortality! Improve nesting success. -

CAHOW RECOVERY PROGRAM for Bermuda’S Endangered National Bird 2017 – 2018 Breeding Season Report

CAHOW RECOVERY PROGRAM For Bermuda’s Endangered National Bird 2017 – 2018 Breeding Season Report BERMUDA GOVERNMENT Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros, Senior Conservation Officer Terrestrial Conservation Division Department of Environment and Natural Resources “To conserve and restore Bermuda’s natural heritage” 2017 - 2018 Report on Cahow Recovery Program 1 Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer RECOVERY PROGRAM FOR THE CAHOW (Bermuda Petrel) Pterodroma cahow BREEDING SEASON REPORT For the Nesting Season (October 2017 to June 2018) Of Bermuda’s Endangered National Bird Fig. 1: 80-day old Cahow (Bermuda petrel) fledgling with remnants of natal down (photo by David Liittschwager) Cover Photo: drone photo of Green Island (foreground) And Nonsuch Island in the Castle Islands Nature Reserve, The sole breeding location of the Cahow (Patrick Singleton) 2017 - 2018 Report on Cahow Recovery Program 2 Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer CONTENTS: Page No. Section 1: Executive Summary: ............................................................................................... 5 Section 2: (2a) Management actions for 2017-2018 Cahow breeding season: ......................................... 7 (2b) Use of candling to check egg fertility and embryo development: .................................. 10 (2c) Cahow Recovery Program – summary of 2017/2018 breeding season: ......................... 11 (2d) Breakdown of breeding season results by nesting island: ............................................. -

Assessing the Relative Vulnerability of Migratory Bird Species to Offshore Wind Energy Projects on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Purpose of Study

Assessing the Relative Vulnerability of Migratory Bird Species to Offshore Wind Energy Projects on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Purpose of Study Initiated study Offshore wind could provide a significant source of energy to the mid-Atlantic and northeastern United States Sensitivity assessments from UK and Europe Need for a sensitivity index for birds offshore in AOCS Project development • Review and synthesis of previous studies • Development of new suite of metrics of sensitivity • Expert review of our proposed methods • Refinement of methods and extension across 177 species of AOCS Previous Studies from Europe include: • Garthe and Hüppop (2004) • Desholm (2009) • Furness and Wade (2012) • Furness, Wade, and Masden (2013) Data were assessed as to how appropriate they were in context of AOCS geographic scope Geographic scope includes South Florida and the Keys Four Reviewers from BOEM Two Reviewers from USFWS One Reviewer from USGS Mark Rehfisch (APEM, Ltd) Bob Furness (MacArthur Green) Chris Thaxter (British Trust for Ornithology) Julia Robinson Willmott Greg Forcey Adam Kent Three Suites of Metrics: • Population sensitivity o Widespread and common species o More restricted-range species with smaller populations • Collision sensitivity o Direct loss of an individual • Displacement sensitivity o Fitness consequences Population Sensitivity Four Metrics • Global Population Size • Percent of Population in AOCS • Threat Ranking • Adult Survival Population Sensitivity Global Population 1 = >3 million individuals 2 = 1–3 million individuals -

Pterodromarefs V1.15.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2017 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Michael O’Keeffe and Kieran Fahy for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds). 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.1 accessed January 2017]). Version Version 1.15 (March 2017). Cover Main image: Soft-plumaged Petrel. At sea, north of the Falkland Islands. 11th February 2009. Picture by Michael O’Keeffe. Vignette: Soft-plumaged Petrel. At sea, north of the Falkland Islands. 11th February 2009. Picture by Kieran Fahy. Species Page No. Atlantic Petrel [Pterodroma incerta] 10 Barau's Petrel [Pterodroma baraui] 27 Bermuda Petrel [Pterodroma cahow] 19 Black-capped Petrel [Pterodroma hasitata] 20 Black-winged Petrel [Pterodroma nigripennis] 31 Bonin Petrel [Pterodroma hypoleuca] 32 Chatham Islands Petrel [Pterodroma axillaris] 32 Collared Petrel [Pterodroma brevipes] 34 Cook's Petrel [Pterodroma cookii] 34 De Filippi's Petrel [Pterodroma defilippiana] 35 Desertas Petrel [Pterodroma deserta] 18 Fea's Petrel [Pterodroma feae] 16 Galapágos Petrel [Pterodroma phaeopygia] 29 Gould's Petrel -

Workshop on Pterodroma and Other Small Burrowing Petrels Workshop Chair

AC10 Doc 14 Rev 1 Agenda Item 16 Tenth Meeting of the Advisory Committee Wellington, New Zealand, 11 – 15 September 2017 Workshop on Pterodroma and other small burrowing petrels Workshop Chair SUMMARY A workshop was held by ACAP on 10 September 2017 with the objective of advancing understanding about best approaches for international cooperation in the conservation of Pterodroma and other small burrowing petrel species. The workshop supported ACAP increasing its role in international conservation actions for gadfly petrels, and in future perhaps the shearwaters, storm petrels and remainder of the Procellaridae. It was recognised that an increased role was constrained by resources and should be focussed on those species that would gain most from international conservation action. Overall these smaller species (both gadfly petrels and others) are affected predominately by land-based threats as opposed to the sea-based threats faced predominantly by the current ACAP species. ACAP may wish to revisit its prioritisation process to focus more on land-based threats. There is a case for a limited number of additions to ACAP’s Annex, but such additions needed to ensure sufficient resources were available, or a strong commitment to obtain such resources, to avoid dilution of existing conservation actions. The refreshing and possible further branding of relevant conservation guidance would be a comparatively straightforward addition to ACAP’s work programme. The creation of additional guidance on collision/grounding, light attraction, and nest finding was recommended. Improved links with other international initiatives addressing invasive species and other land-based pressures were encouraged. ACAP should consider more formal links to specialist groups, working in relevant fields, in order to stimulate further support and expertise. -

July 2008 Newsletter (Pdf)

July 2008 Pelagic UPDATE www.seabirding.com Spring Blitz! May 17 to June 2 In spring 2008, Seabirding ran an unprecedented 17 trips in a row from May 17-June 2. While the diversity was not as high as during the 15 -day stretch last spring, we encountered the usual suspects in the Gulf Stream plus an unexpected species on June 2. We had excellent views of our Gulf Stream “specialty”, the Black-capped Pet- rel, on each day, though May 26 we had our lowest tally for the spring with only 6 or 7 individuals. This was a day with unexpectedly cooler water due to North winds the previous day, resulting in calm seas and Leach’s Storm-Petrels in amazing numbers & close proximity! For a storm-petrel that is sometimes difficult to observe, it was a treat to find groups of this Oceanodroma flying by and sitting in pure flocks on the water for close approach! European Storm-Petrels were seen on two of these trips with the individual on May 18th proving to be the earliest recorded by nine days! The other, seen on May 20th, was a fleeting encounter in the slick on one of the roughest Clymene Dolphin © Kate Sutherland days we were out. We had three encounters with the elusive Bermuda Petrel, twice from Hatteras on May 21 & 28th, and on the Saturday trip from Oregon Inlet May 24th. (Some birders on that trip saw all three of the rare gadfly petrels that Saturday!) Dolphin Days While Trindade Petrels were in short supply with only a few individuals seen this spring, Fea’s Petrels were in good numbers with the most individuals ever seen in one day May 20 (most likely 4 individuals!).