Re: Domestic Violence Law Reforms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY FILECOPY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 2523a-MOR Public Disclosure Authorized KINGDOM OF MOROCCO STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT OF THE VECETABLE PRODUCTION AND MARKETING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized August 16, 1979 Public Disclosure Authorized Europe, Middle East and North Africa Projects Department Agriculture II Division This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. ! CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Currency Unit - Dirham (DH) US$1 DH4.0 DH 1 = US$0.25 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1 millimeter (mm) - 0.039 inch (in) 1 meter (m) - 39 inches (in) 1 kilometer (km) - 0.62 mile (mi) 1 hectare (ha) - 2.47 acres 1 square meter (m2) - 10.76 square feet (sq ft) 1 cubic meter (m3) - 35.31 cubic feet (cu ft) 1 liter (1) - 0.264 US gallon (gal) 1 hectoliter (hl) - 26.4 US gallons (gal) 1 kilogram (kg) - 2.205 pounds (lb) 1 metric ton (m ton) - 2,205.00 pounds (lb) 1 bar - 14.666 pounds per square inch (psi) 1 kilometer per hour (km/h) - 0.6 mile per hour (mph) GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FISCAL YEAR JANUARY 1 - DECEMBER 31 FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY ABBREVIATIONS CLCA Caisses Locales de Crédit Agricole CNCA Caisse Nationale de Crédit Agricole CRCA Caisses Régionales de Crédit Agricole DE Rural EngineeringDirectorate DMV AgriculturalDevelopment Directorate DRA AgriculturalResearch Directorate BEC European Economic Community FAO/CP Food and Agriculture Organization/CooperativeProgram ICB InternationalCompetitive Bidding MARA Ministry of Agriculture OCE Office de Commercialisationet d'Exportation SASMA Société Agricole de Services au Maroc This document ha a restrictod distribution and may be used by rocipientsonly in the performance of thoir officiai dutbu. -

International Health Programs 1015 Fifteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C

Jim* -J AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION International Health Programs 1015 Fifteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 AN EVALUATION OF THE POPULATION AND FAMILY PLANNING SUPPORT PROJECT IN MOROCCO A Report Prepared By: JEAN LECOMTE, M.D., TEAM LEADER fMIRIAM LABBOK, M.D., M.P.H. JAY FRIEDMAN, M.A. During The Period: NOVEMBER 30, 1981 - DECEMBER 21, 1981 Supported By The: U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (ADSS) AID/DSPE-C-0053 AUTHORIZATION: Ltr. AID/DS/POP: 4/12/82 Assgn. No. 582127 EDITOR'S NOTE Jean LeComte, M.D., an independent consultant, and Miriam Labbok, M.D., M.P.H., Department of Population Dynamics, School of Hygiene and Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, are consultants to the American Public Health Association. Mr. Jay Friedman, M.A., is employed by the Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia. -i CONTE NTS Page EDITOR'S NOTE ....... ... ............................ i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........ .......................... .. v ABBREVIATIONS ....... .. ............................ xv I. HEALTH POLICY AND POPULATION IN MOROCCO ..... ............ 1 Research into Alternative Health Care ..... ............. 3 Health Protection of Mothers ..... ................ 3 Reduction of Infant Mortality .... ................... 3 II. FAMILY PLANNING WITHIN HEALTH POLICY .. ............ 5 Family Planning as Part of Basic Health ..... ............ 5 Sterilization ....... .. ......................... 6 Abortion ............... ................. 7 Commercial Sale of Subsidized Contraceptives . ....... 7 Acceptability of -

Morocco and United States Combined Government Procurement Annexes

Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 MOROCCO AND UNITED STATES COMBINED GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ANNEXES ANNEX 9-A-1 CENTRAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES This Chapter applies to procurement by the Central Level Government Entities listed in this Annex where the value of procurement is estimated, in accordance with Article 1:4 - Valuation, to equal or exceed the following relevant threshold. Unless otherwise specified within this Annex, all agencies subordinate to those listed are covered by this Chapter. Thresholds: (To be adjusted according to the formula in Annex 9-E) For procurement of goods and services: $175,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] For procurement of construction services: $ 6,725,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] Schedule of Morocco 1. PRIME MINISTER (1) 2. NATIONAL DEFENSE ADMINISTRATION (2) 3. GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE GOVERNMENT 4. MINISTRY OF JUSTICE 5. MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND COOPERATION 6. MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR (3) 7. MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATION 8. MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION, EXECUTIVE TRAINING AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 9. MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION AND YOUTH 10. MINISTRYOF HEALTH 11. MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PRIVATIZATION 12. MINISTRY OF TOURISM 13. MINISTRY OF MARITIME FISHERIES 14. MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORTATION 15. MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (4) 16. MINISTRY OF SPORT 17. MINISTRY REPORTING TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND CHARGED WITH ECONOMIC AND GENERAL AFFAIRS AND WITH RAISING THE STATUS 1 Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 OF THE ECONOMY 18. MINISTRY OF HANDICRAFTS AND SOCIAL ECONOMY 19. MINISTRY OF ENERGY AND MINING (5) 20. -

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Rabies in El Jadida Region, Morocco

veterinary sciences Article Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Rabies in El Jadida Region, Morocco Khadija Bouaddi 1,2,*, Abdelali Bitar 2, Mohammed Bouslikhane 3, Abdesslam Ferssiwi 2, Aziz Fitani 4 and Philip Paul Mshelbwala 5 1 Provincial Veterinary Service of El Jadida, National Food Safety Office, ONSSA, El Jadida 24000, Morocco 2 Nutritional Physiopathology and Toxicology Team, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Chouaib Doukkali University, El Jadida 24000, Morocco; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (A.F.) 3 Department of Pathology and Veterinary Public Health, Institute of Agronomy and Veterinary Medicine Hassan II, BP 6202, Rabat-Instituts, Rabat 10000, Morocco; [email protected] 4 Private Veterinarian, El Jadida 24000, Morocco; azizfi[email protected] 5 Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Abuja, Abuja 900001, Nigeria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 December 2019; Accepted: 6 February 2020; Published: 1 March 2020 Abstract: The aim of this study was to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding rabies in the El Jadida region, Morocco. We conducted a cross-sectional survey using a structured questionnaire among randomly selected residents across 24 study sites. In total, 407 respondents took part in the survey. The majority (367, 92%) were male and had no formal education (270, 66%). Some (118, 29%) believed that rabies does not affect humans. Most respondents (320, 79%) were aware that vaccination could prevent rabies, but nevertheless did not vaccinate their dogs (264, 64.9%) and allowed their dogs to roam freely in search of food. Some (52.8%) would visit traditional healers for treatment in the event of a dog bite incident. -

Inventory of Medicinal Plants Prescribed by Traditional Healers in El Jadida City and Suburbs

[Downloaded free from http://www.greenpharmacy.info on Thursday, October 16, 2014, IP: 223.30.225.254] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Inventory of medicinal plants prescribed by traditional healers in El Jadida city and suburbs TICLE R (Morocco) A Pr Ahmed El Abbouyi, Najoie Filali‑Ansari, Pr Said EL Khyari, Halima Loukili L Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Laboratory of Biochemistry, Nutrition and Valorization of Natural Resources, El Jadida, Morocco A Background: Traditional medicine is still popular in Morocco since it is an important form of health care of many people. Aims: The present ethnobotanical survey aims to make an inventory of plants and their medicinal uses by the population of El Jadida city and IGIN suburbs (Morocco). Settings and Design: Given the nature of the project, it was decided that a qualitative approach would provide R the most effective tool for data collection. For that a semi-structured interview was used with a set of pre-determined questions. Materials and Methods: The study was conducted from October 2010 to April 2011. Forty-five interviews were conducted, each one O involving more than one visit and sometimes with the participation of more than one informant. Statistical Analysis: All values are expressed in percentage. Results: A total of 102 species are inventoried belonging to 88 genera and 42 families of which 3 dominate: Apiaceae (13.7%), Lamiaceae (10.8%) and Asteraceae (8.8%). The most remedies are administered orally (88.2%) and prepared with an aqueous base, preferentially as decoction (42.2%), infusion (36.3%) or maceration (4.9%). -

KINGDOM of Morocco Minstry of Economy and Finance Department of Studies and Financial Forecasts

KINGDOM of Morocco Minstry of Economy and Finance Department of Studies and Financial Forecasts AA CCoommppaarraattiivvee SSttuuddyy ooff RReeggiioonnaall CCoonnttrriibbuuttiioonnss ttoo tthhee CCrreeaattiioonn oof NNaattiioonnaall WWeeaalltthh Ordering and Reconfiguration of Local Productive Systems in Support of Mapping Proposed by Advisory Commission for Regionalisation, June 2011 PIB régional : contribution sectorielle à la création de la richesse nationale 2 Table of content Table of Content‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 2 List of Figures‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 3 Introduction‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 5 1. Regional Economic Cartography : Comparison between the Existing and the Proposed Mapping‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 5 2. Regional GDP Concentration in Four Regions‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Erreur ! Signet non défini. 3. Sector-based Configuration of Regional Added Value ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 13 3.1. Regionalised Added Value in the Primary Sector ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 13 3.1.1. Regionalised Added Value in Agriculture ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 16 3.1.2. Regionalised Added Value in the Fishing Industry ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 17 3.2. Regioalized Added Value -

1984 7 ,887000 January

. .. ..- .. j .-.. .. f 4 ; .gI." • -?O.k1ATION/..MILYPL.NNING SUPPORT PROJECT, PHASE . USAID/MOROCCO 608-0133 -' ___ , The project aims to establish and demonsE-ra-e-w'ithin'_ oth 'e bt i a- . private saccors a capability to plan, implement, and evaluate cost-effective family planning programs. The project contains a variety of subactivities (12 separate activities) designed to promote the use of modern contraceptives among the target popuiation; raise the levels of awareness of population problems and commitment to _.$ugus-23...._ ,887,0001787S 608-84-04 January 17, 1984 7 at-ar (Somc1t/) 3 .1797 ,887,- "i 'ut- . I Ursula Nadolny 1Robert C. Chase i ission Director TrTinal _-gvauation _ _ Officer_ _ _ _ _ ___ ___ I_____ IE+C programs and increased availability of services. The subactivities include education, referral services, informational materials design, training, commodity support, and some data gathering/analysis/dissemination. This was the final evaluation of this project and its 12 inter-related sub-activities, prior to the commencement of "Phase III" activities. The general objectives of the evaluation were to determine the progress of the project and of the 12 component sub activities; review the status of the family planning/health/nutrition services provided; I and suggest future directions for family planning activities and funding within the GOM, and potential spheres of cooperation with other ministries and agencies and with individuals outside the formal public health system. Family planning activities in Morocco have progressed substantially during the past 5 years of project activity. Contraceptive Prevalence (CP) estimates indicate that the nationwide CP has more than dbubled from 12% (1978) to 27% (1983). -

Appels D'offre Ouverts : Collectivités Locales (Classés Par Date Limite De Remise Des Plis)

Appels d'Offre ouverts : Collectivités Locales (classés par date limite de remise des plis) Référence| Date limite Publié Lieu Catégorie Contexte/ Objet de remise le d'éxecution Programme des plis 18/01/2017 Fournitures 01/2017/CTSA/ PROJET DE LA REALISATION DES DEUX LIGNES DE Elfida Derb 04/07/2017 F - TRAMWAY T3 & T4 DE LA VILLE DE CASABLANCA Soltane 10:00 FOURNITURE DU MATERIEL ROULANT 10/02/2017 Fournitures 12/2017/CNSS Acquisition de mobilier de bureau pour l’encadrement du siège Aïn Sebaa 03/07/2017 - de la CNSS en deux lots distincts : . Lot 1 : Bureaux et table 10:00 de réunion . Lot 2 : Mobilier de rangements 18/04/2017 Travaux 05/2017/R.C.S. Travaux de creusement de deux forages d’eau potables Sidi Bennour 01/06/2017 P.C.T - respectivement au centre de la Commune de Tamda et au 11:00 Douar El GUANTOUR à la Commune de Tamda Province de Sidi Bennour. 15/04/2017 Services 08/2017/ONO la gestion du service de restauration au profit des étudiants de Casablanca 01/06/2017 USC - la cité universitaire Casablanca 11:00 09/04/2017 Fournitures PM494191/201 Fourniture de jeux de paniers pour réchauffeurs d’air Mohammadia 01/06/2017 7/DXM - Ljunstrom en service à la Direction Exploitation Mohammedia. 09:00 09/04/2017 Fournitures PM494613/201 Fourniture des groupes motopompes lavage grille filtrante Mohammadia 01/06/2017 7/DXM - pour la Direction Exploitation Mohammedia. 09:00 19/04/2017 Travaux 07/DRPJL/2017 Travaux d’approfondissement du chenal d’accès du port de El jadida 31/05/2017 - Jorf Lasfar. -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: AB5044 Morocco Urban and Rural Water Systems Project Name Public Disclosure Authorized Region MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Sector Water supply (100%) Project ID P100397 Borrower(s) Office National de l’Eau Potable (ONEP), Morocco with a guarantee by the Government of Morocco Implementing Agency Office National de l’Eau Potable (ONEP) Station de Traitement Akrach Route des Zaers,-Akrach Rabat Morocco Public Disclosure Authorized Tel: (212-537) 650-695 Fax: (212-537) 726-707 Environment Category [ ] A [X] B [ ] C [ ] FI [ ] TBD (to be determined) Date PID Prepared September 9, 2009 Date of Appraisal March 15, 2010 Authorization Date of Board Approval May 27, 2010, 2009 1. Country and Sector Background Morocco stands out in the region for its political opening and structural reform ambition. Since 1999, King Mohamed VI has led the country to broader political participation while Public Disclosure Authorized ensuring security and stability. Morocco’s civil society is flourishing, thousands of NGOs are active today, and a dynamic press corps is at work. Comprehensive pro-growth structural reforms have been launched in the last decade in areas of decentralization, trade, customs, transport deregulation, privatization of telecoms, housing sector reform, financial sector reform, public administration modernization, agriculture reform, etc. Along with sustained investment and targeted social development and protection reforms, these initiatives set the stage for economic growth and social development. Despite undeniable gains, growth remains unsteady, still vulnerable to droughts, and unemployment rates high especially among the youth. Social protection, poverty reduction and human development are Government priorities. -

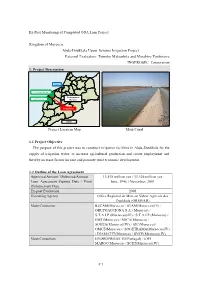

Kingdom of Morocco Abda-Doukkala Upper Scheme Irrigation Project External Evaluators: Tomoko Matsushita and Masahiro Yoshizawa INGEROSEC Corporation 1

Ex-Post Monitoring of Completed ODA Loan Project Kingdom of Morocco Abda-Doukkala Upper Scheme Irrigation Project External Evaluators: Tomoko Matsushita and Masahiro Yoshizawa INGEROSEC Corporation 1. Project Description Rabat El Jadida Province The Kingdom of Safi Province Morocco Project Site Algeria Project Location Map Main Canal 1.1 Project Objective The purpose of this project was to construct irrigation facilities in Abda-Doukkala for the supply of irrigation water, to increase agricultural production and create employment and thereby increase farmer income and promote rural economic development. 1.2 Outline of the Loan Agreement Approved Amount/ Disbursed Amount 13,548 million yen / 13,426 million yen Loan Agreement Signing Date / Final June, 1996 / November, 2001 Disbursement Date Ex-post Evaluation 2005 Executing Agency Office Regional de Mise en Valeur Agricole des Doukkala (ORMVAD) Main Contractor BECAM(Morocco) / STAM(Morocco)(JV) / GRUPOACCIONA.S.A.( Morocco) / S.T.A.I.P.(Morocco)(JV) / S.T.A.I.P.(Morocco) / EMT(Morocco) / SOCA(Morocco) / SOGEA(Morocco)(JV) / AIC(Morocco)/ OMCE(Morocco) / SOGETRAMA(Morocco)(JV) / DIAMATIT(Morocco) / SNCE(Morocco)(JV) Main Consultant HYDROPROJECTO(Portugal) / EWI MAROC(Morocco) / SCET(Morocco)(JV) 3-1 1.3 Background of Ex-post Monitoring Moroccan agriculture consumes over 90% of the usable water resources. Considering the increase in demand for industrial-use water and water supply as the country’s industry develops and its cities grow, there is a strong possibility that in the future the proportion of irrigation water could be limited. Therefore the efficient use of water through the construction of irrigation facilities has been an urgent issue. -

Nouveau Découpage Régional Au Maroc.Pdf

01/03/13 Nouveau découpage régional au Maroc - collectivités au Maroc Rechercher dans ce site Accueil Actualités Nouveau découpage régional au Maroc Régions Chiffres Clès Documentations Régions Populations en 2008 Provinces et Préfectures Etudes Réglementations Effectif Part du Part de Nombre Liste Total Rural l’urbain Fonds de Soutien RendezVous Région 1 : TangerTétouan 2830101 41.72% 58.28% 7 Tanger‑Assilah Avis d'Appel d'Offres (Préfecture) Contact Us M'Diq ‑ Fnidq Affiliations (Préfecture) Chefchaouen (Province) Fahs‑Anjra (Province) Larache (Province) Tétouan (Province) Ouezzane (Province) Région 2 : Oriental et Rif 2434870 42,92% 57,08% 8 Oujda Angad (Préfecture) Al Hoceima (Province) Berkane (Province) Jrada (Province) Nador (Province) Taourirt (Province) Driouch (Province) Guercif (Province) Région 3 : Fès‑Meknès 4022128 43,51% 56,49% 9 Meknès (Préfecture) Fès (Préfecture) Boulemane (Province) El Hajeb (Province) Ifrane (Province) Sefrou (Province) Taounate (Province) Taza (Province) Moulay Yacoub (Province) Région 4 : Rabat‑Salé‑ 4272901 32,31% 67,69% 7 Rabat (Préfecture) Kénitra (Sale (Préfecture ﺗﺭﺟﻣﺔ Skhirate‑Temara (Préfecture) Template tips Learn more about working with Kenitra (Province) templates. Khemisset (Province) How to change this sidebar. Sidi Kacem (Province) Sidi Slimane (Province) https://sites.google.com/site/collectivitesaumaroc/nouveau-dcoupage-rgional 1/3 01/03/13 Nouveau découpage régional au Maroc - collectivités au Maroc Région 5 : Béni Mellal‑ -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FILECOPY FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.1156-MOR Public Disclosure Authorized STAFF PROJECT REPORT THE SIDI CHEHO-AL MASSIRA HYDRO PROJECT MOROCCO Public Disclosure Authorized June 11, 1976 Public Disclosure Authorized Europe, Middle East and North Africa Regional Office This documentbas a restrieteddistribution and may be used by recipients only ln the performanceof their officiaiduties. Its contents may not otherwisebe disclsed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (April 1976) Currency Unit Dirham (DH) DH1 = Centimes (ctm) 100 DH1 = US$0.23 DH4.38 = US$1.00 DH 1,000 = US$228.31 DH 1,000,000 (MDH1) = US$228,310 (MUS$ 0.228) WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1 meter (m) 3.281 feet (h) 2 1 hectare (ha; 10,000 m ) = 2.471 acres (ac) 1 square kilometyr (km2 ) 0.386 square mile (mi2 ) 1 cubic meter (m ) = 35.315 cubic feet (ft3 ) = 264.2 gallon (gal) = 6.289 barrels (bbl) = 220.0 Imperial gallons (Igal) 1 kilogram (kg) = 2.206 pounds (lb) 1 ton (t; metric; 1,000 kg) 1.100 short tons (sh tons) 1 kilowatt (kW) = 1,000 Watts (103 W) 1 Megawatt (MW) = 1,000 kW (10 W = 103 kW) 1 kilowatthour (kWh) = 1,000 Watthours (103 Wh) = 860.4 kilocalories (kcal) 1 Megawatthour (MWh) = 1,000 kilowatthours 1 kilovolt (kV) = 1,000 Volts (V) 1 kilovolt ampere (kVA) = 1,000 Volt amperes (103 VA) 1 Megavolt ampere (MVA) 1,000 kilovolt amperes 1 kilocalory (kcal) = 3.968 British thermal units (Btu) 1 ton coal equivalent (tce) = 7.106 kcal 1 Hertz (Hz) = 1 cycle/second per second; per hour; per day; per