Whitechapel High Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues I — Ii — Iii — Iv the — Unlimited — Edition

THE — UNLIMITED EDITION ISSUES I — II III IV Many thanks to all our contributors This issue of The Unlimited Edition has for their hard work been printed locally by Aldgate Press, with recycled paper by local Published by supplier Paperback We Made That www.wemadethat.co.uk www.aldgatepress.co.uk www.paperback.coop Designed by Andrew Osman & Stephen Osman www.andrewosman.co.uk www.stephenosman.co.uk THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 2 THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 3 is to record and explore the familiar, the transitory nature of the area for the High Street 2012 Historic Buildings Officer and to celebrate and speculate on the present day commuter. for Tower Hamlets Council, also gives possibilities that lie in its future. Expanding outwards from this critical us his personal perspective on some of In our first issue, ‘Survey’, we focus on highway, articles from Ruth Beale and the restoration works that form part the existing nature of the High Street. Clare Cumberlidge reveal the tight mesh of the wider heritage remit of the High Olympic Park Our contributors have been invited from of social, cultural, ethnic and economic Street 2012 initiative. Whitechapel Market a wide range of disciplines: they have fabric that surrounds the High Street in may hold new delights for you once you Holly Lewis, We Made That watched, read, analysed, photographed Aldgate and Wentworth Street. Such have imagined the stallholders as part of and illustrated the High Street to bring to hidden links and ties are further elaborated a life-sized ‘Happy Families’ card game, Stratford Welcome to Issue I of The Unlimited you a collection of articles as varied, by Esme Fieldhouse and Stephen Mackie, as Hattie Haseler has done, or considered Ω Ω Edition. -

PDU Case Report XXXX/YY Date

planning report D&P/3147/01 5 March 2014 100 Whitechapel Road Land and Building Fronting Fieldgate Street & Vine Court, London, E1 1JG in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets planning application no. PA/13/03049 Strategic planning application stage 1 referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 The proposal Demolition of existing vehicle workshop and erection of extension to the prayer hall at the East London Mosque, residential development comprising 241 open market and affordable housing units including studio, one, two, three and four bedroom apartments in buildings up to 18 storeys, basement parking, public realm improvements, pedestrian link from Fieldgate Street to Whitechapel Road. The applicant The applicant is Alyjiso and Fieldgate Ltd. and the architect is Webb Gray. Strategic issues The development of this mixed-use scheme accommodates both the extension of the East London Mosque and residential uses on a constrained site within the City Fringe Opportunity Area. The proposal is broadly in accordance with strategic planning policy, and is supported. However, further discussion is required regarding housing quality, children’s play space provision, inclusive design, sustainability and transport. Recommendation That Tower Hamlets Council be advised that while the application is generally acceptable in strategic planning terms the application does not comply with the London Plan, for the reasons set out in paragraph 86 of this report; but that the possible remedies set out in this paragraph could address these deficiencies. Context 1 On the 20 January 2014 the Mayor of London received documents from Tower Hamlets Council notifying him of a planning application of potential strategic importance to develop the above site for the above uses. -

Stepney Consultation: Salmon Lane Area

Stepney Consultation: Salmon Lane Area Tower Hamlets is committed to making the borough a safer place which people can take pride in. We are looking to deliver a range of improvements to our streets for everyone’s benefit, whether you walk, cycle, use public transport or drive. The first area to be reviewed is Stepney as we have received funding through Transport for London and development contributions to improve the area. “This is an exciting opportunity to improve the streets of Stepney. There are lots of small changes we could make which would really improve the streets in this area and discourage dangerous driving. We want to know your ideas – where do you think a small change would make a big improvement? We’ve put forward some of our ideas but we know it is local residents who know their streets best. So share your ideas and together we can Transform Stepney and make it an even better place to live. We’re rolling out improvements in the Stepney area first of all, but other areas throughout the borough will follow soon.” - the Mayor The Transforming Stepney’s Streets improvement area is framed by the A13, Sidney Street, A11, and Mile End Park and has approximately 9,500 residential homes. We are planning to make a range of improvements to the area, to help create better connected walking and cycling routes (including to the many schools in the area), making our roads safer and reducing the volume of traffic using these roads as a ‘rat run’. We also want to improve the look and feel of the area, making it an even more enjoyable, and safer, place to live, work and visit. -

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

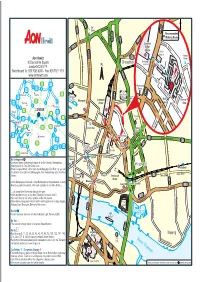

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Queen Mary, University of London Audio Walking Tour Exploring East London

Queen Mary, University of London Audio walking tour exploring east London www.qmul.ac.uk/eastendtour 01 Liverpool Street Station 07 Brick Lane Mosque Exit Liverpool Street Station via Bishopsgate West exit (near WH Go up Wilkes Street. Turn right down Princelet Street. Then turn right Smith). You will come out opposite Bishopsgate Police Station. Press on to Brick Lane. The Mosque is 30m up on the right-hand side. Press play on your device here. Then cross Bishopsgate. Walk to Artillery play on your device. Lane, which is the first turn on the right after the Woodin’s Shade Pub. 08 Altab Ali Park 02 Artillery Passage Follow Brick Lane (right past Mosque) for 250m (at the end Brick Lane Follow Artillery Lane round to the right (approximately 130m). Artillery becomes Osborn Street) to Whitechapel Road. Altab Ali Park on the Passage is at the bottom on the right (Alexander Boyd Tailoring shop is opposite side of Whitechapel Road, between White Church Lane and on the corner). Press play on your device. Adler Street. Press play on your device. 03 Petticoat Lane Market 09 Fulbourne Street Walk up Artillery Passage. Continue to the top of Widegate Street (past At the East London Mosque cross over Whitechapel Road at the traffic the King’s Store Pub). Turn left onto Middlesex Street (opposite the lights, turn right and walk 100m up to the junction of Fulbourne Street Shooting Star Pub). Continue to the junction with Wentworth Street (on (on the left). Press play on your device. the left). Press play on your device. -

Davenant Foundation School Foundation School

DAVENANT DAVENANT FOUNDATION SCHOOL FOUNDATION SCHOOL Chester Road, Loughton, Essex IG10 2LD. Telephone: 020 8508 0404 Facsimile: 020 8508 9301 E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @DavenantFS @Davenant6thform “a community based firmly on Christian principles” Ofsted “parental commitment and support are significant factors in the school’s success” Ofsted “the school’s extra curricular provision is particularly strong” Ofsted www.davenantschool.co.uk Nurturing Mind, Body and Spirit Produced by: The School Brochure Specialist, FM Litho Design and Print. Tel: 01787 479479 • [email protected] • www.fmlitho.co.uk DAVENANT “a Christian school valuing the past with a vision of the future” It has been over fifty years since Davenant moved from Whitechapel to our present site, here in Loughton. The school has grown to be a highly regarded, Christian ecumenical school achieving excellent results for students of all abilities. Students, staff and the wider community work very hard to make Davenant a successful school. We see ourselves as a community that promotes individual excellence and nurtures the God given potential within each of us. Our ethos is based firmly on the commitment to “nurture mind, body and spirit” and, therefore, we work hard to ensure each student not only achieves their academic potential but also has a range of opportunities to be enriched and to enjoy new experiences away from the classroom. Also, Davenant is highly regarded for the work done in training and developing teachers so that our students receive the high quality teaching they deserve. Our expectations of each other are high. We demand a great deal of our students-hard work, the desire to learn, a determination to succeed and a willingness to contribute fully to the life of the school. -

SAVED by the BELL ! the RESURRECTION of the WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a Proposal by Factum Foundation & the United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust

SAVED BY THE BELL ! THE RESURRECTION OF THE WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a proposal by Factum Foundation & The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust Prepared by Skene Catling de la Peña June 2018 Robeson House, 10a Newton Road, London W2 5LS Plaques on the wall above the old blacksmith’s shop, honouring the lives of foundry workers over the centuries. Their bells still ring out through London. A final board now reads, “Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 1570-2017”. Memorial plaques in the Bell Foundry workshop honouring former workers. Cover: Whitechapel Bell Foundry Courtyard, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. Back Cover: Chains in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. CONTENTS Overview – Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 1 A Brief History of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel 9 2 The Whitechapel Bell Foundry – Summary of the Situation 11 3 The Partners: UKHBPT and Factum Foundation 12 3 . 1 The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust (UKHBPT) 12 3 . 2 Factum Foundation 13 4 A 21st Century Bell Foundry 15 4 .1 Scanning and Input Methods 19 4 . 2 Output Methods 19 4 . 3 Statements by Participating Foundrymen 21 4 . 3 . 1 Nigel Taylor of WBF – The Future of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 21 4 . 3 . 2 . Andrew Lacey – Centre for the Study of Historical Casting Techniques 23 4 . 4 Digital Restoration 25 4 . 5 Archive for Campanology 25 4 . 6 Projects for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 27 5 Architectural Approach 28 5 .1 Architectural Approach to the Resurrection of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel – Introduction 28 5 . 2 Architects – Practice Profiles: 29 Skene Catling de la Peña 29 Purcell Architects 30 5 . -

Leamouth Leam

ROADS CLOSED SATURDAY 05:00 - 21:00 ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00TO WER 4 2- 12:30 ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 14:00 3 3 ROUTE MAP ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 18:00 A1 LEA A1 LEA THE GHERR KI NATCLIFF RATCLIFF RATCLIFF CANNING MOUTH R SATURDAY 4th AUGUST 05:00 – 21:00 MOUTH R SUNDAY 5th AUGUST 05:00 – 14:00 LIMEHOUSE WEST BECKTON AD AD BANK OF WHITECHAPEL BECKTON DOCK RO SUNDAY 5th AUGUST 14:00 – 18:00 TOWN OREGANO DRIVE OREGANO DRIVE CANNING LLOYDS BUILDING SOUTH ST PAUL S ENGL AND Limehouse DLR SEE MAP CUSTOM HOUSE EAST INDIA O EAST INDIA DOCK RO O ROYAL OPER A AD AD CATHED R AL LEAMOUTH DLR PARK OHO LIMEHOUSE LIMEHOUSBecktonE Park Y Y HOUSE Cannon Street Custom House DLR Prince Regent DLR Cyprus DLR Gallions Reach DLR BROMLEY RIGHT A A ROADS CLOSED SUNDAY 05:00 - 18:00 Royal Victoria DLR W W Mansion House COVENT Temple Blackfriars POPLAR DLR DLR Tower Gateway LE A MOUTH OCEA OCEA Monument COMMERC COMMERC V V GARDEN IAL ROAD East India RO UNDABOU T IAL ROAD ExCEL UNIVERSI T Y ROYAL ALBERT SIL SIL ITETIONAL CHASOPMERSETEL Tower Hill Blackwall DLR OF EAST LONDON SEE MAP BELOW RT R AIT HOUSE MILLENIUM ROUNDABOUT DLR Poplar E TOWN GALLE RY BRIDGE A13 VENU A13 VENUE SAFFRON A SAFFRON A SOUTHWARK THE TO WER Westferry DLR DLR BLACKWALL Embankment ROTHERHITH E THE MUSEUM AD AD CLEOPATRA’S BRIDGE OF LONDON EAST INDIA DOCK RO EAST INDIA DOCK RO LONDON WAPPING T UNNEL OF LONDON West India A13 A13 LEAMOUTH NEED LE SHADWELL LONDON CI T Y BRIDGE DOCK L A NDS Quay BILLINGSGATE AIRPOR T A13 K WEST INDIA DOCK RD K WEST INDIA DOCK RD LEA IN M ARKET IN LEAM RATCLIFF L L SE SE MOUT WAY TATE MODERN HMS BELFAST U U SPEN O O AD A N H H A AY A N W E TOWER E E 1 ASPEN 1 H R W E G IM IM 2 2 L L OREGANO DRIVE 0 W 0 OWER LEA CROSSING L CANNING P LOWER LEA CROSSIN BRIDGE 6 O 6 O EAST INDIA DOCK RO POR AD R THE O2 BL ACK WAL L Y T LIMEHOUSE PR ESTO NS A T A A C C HORSE SOUTHWARK W V RO AD T UNNEL O O E V T T . -

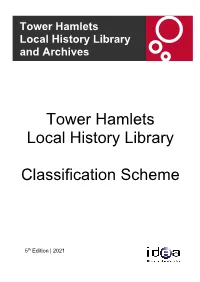

Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme – 5Th Edition 2021

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme 5th Edition | 2021 Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme – 5th Edition 2021 Contents 000 Geography and general works ............................................................... 5 Local places, notable passing events, royalty and the borough, world wars 100 Biography ................................................................................................ 7 Local people, collected biographies, lists of names 200 Religion, philosophy and ethics ............................................................ 7 Religious and ethical organisations, places of worship, religious life and education 300 Social sciences ..................................................................................... 11 Racism, women, LGBTQ+ people, politics, housing, employment, crime, customs 400 Ethnic groups, migrants, race relations ............................................. 19 Migration, ethnic groups and communities 500 Science .................................................................................................. 19 Physical geography, archaeology, environment, biology 600 Applied sciences ................................................................................... 19 Public health, medicine, business, shops, inns, markets, industries, manufactures 700 Arts and recreation ............................................................................... 24 Planning, parks, land and estates, fine arts, -

13-20 Settles Street

13-20 SETTLES STREET WHITECHAPEL, LONDON E1 Freehold refurbishment opportunity 1 13–20 SETTLES STREET PROVIDES AN OPPORTUNITY TO ACQUIRE A RARE FREEHOLD PROPERTY IN AN AREA EXPERIENCING EXTRAORDINARY GROWTH. TO THE WEST ALDGATE IS BEING TRANSFORMED, TO THE NORTH THE TECH SECTOR EXPANDS FROM SHOREDITCH, AND TO THE EAST WHITECHAPEL WILL RECEIVE CROSSRAIL – JUST TWO MINUTES JOURNEY TIME FROM BOTH CANARY WHARF AND LIVERPOOL STREET. 2 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Freehold • A distinctive 1930s neo-Georgian property within the Whitechapel vision area • Excellent transport connectivity being approximately 500m from Whitechapel and Aldgate East Underground stations • The existing building comprises a net internal area of 17,107 sq ft (1,589 sq m) of office and ancillary accommodation arranged over lower ground, ground and one upper floor • Single let on an FRI lease to Trillium for Department of Work and Pensions at a rent of £150,000 per annum, expiring 1st April 2018 • The building has planning consent for a comprehensive refurbishment and addition of 3 further floors, with a proposed net internal area of 22,682 sq ft (2,107 sq m), and a change of planning use from A2 to B1 (offices) • Offers are invited in excess of £7,000,000, subject to contract and exclusive of VAT • A purchase at the level reflects a low capital value of £409 per sq ft on the existing accommodation and £308 per sq ft on the consented scheme 1 2 THE SHARD THE CITY OF LONDON TOWER OF LONDON ALDGATE ST KATHARINE DOCKS STATION BRICK LANE GOODMAN’S FIELDS SPITALFIELDS MARKET TOWER HILL STATION ALDGATE EAST STATION WHITECHAPEL STATION ROYAL LONDON HOSPITAL 3 4 LOCAL AREA Aldgate and Whitechapel are evolving to become an integral part of London’s Tech Belt. -

Capital Grant Release from the Whitechapel High Street Fund To

Commissioner Decision Report 24 May 2016 Report of: Classification: Aman Dalvi Unrestricted Corporate Director, Development and Renewal Report Title: Whitechapel High Street Fund as grant to London Small Business Centre to deliver capital refurbishment and accessible workspace at 206 Whitechapel Road (SITE 2) Originating Officer(s) Duncan Brown, Strategic Project Manager, Whitechapel Delivery Team Wards affected Whitechapel, Stepney Green, Spitalfields-and-Banglatown, Bethnal Green Key Decision? Yes Community Plan Theme A great place to live; A fair and prosperous community; A safe and cohesive community EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In July 2015, the Council entered into a jointly sponsored funding agreement known as the Whitechapel High Street Fund (WHSF) with the Greater London Authority (GLA) valued at £1.123 million to be spent in the geographical boundary of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan SPD area by April 2017. The agreement consists of £520,000 awarded by the GLA matched by a £603,000 contribution from the Council (LBTH). Of this funding, £725,000 is allocated as capital funding for the refurbishment and reuse of vacant and underused spaces in order to contribute towards the delivery of workspace within the Whitechapel area. Of the £725,000 amount, the Council has until 30th September 2016 to allocate approximately £400,000 of unspent GLA match funding towards capital projects, or it must return these monies back to the GLA. Therefore timescales are critical to project spend being delivered within this timeframe. Following a six month pre-qualified site selection process (Call for Spaces) that commenced in September 2015 and bid selection process (Call for Bids) thereafter, this report recommends funding be released against SITE 2 (Royal Mail Group owned vacant unit at 206 Whitechapel Road) from the Whitechapel High Street Fund as grant directly towards the London Small Business Centre, to procure and deliver refurbishment works to enable new accessible workspace provision. -

FOI 9311 Parks in LB Tower Hamlets and List of Parks by Size Since 1938

FOI 9311 Parks created since 1938 Could you please supply a list of all open spaces created from January 1938 to December 2012. Please supply the area of each new open space when created History of parks and open spaces in Tower Hamlets, and their heritage significance The History of Parks and Open Space in Tower Hamlets The parks and open spaces of Tower Hamlets have come about through a variety of processes. Some public open spaces were the result of deliberate design or policy, while others are the result of historic accident or expedience. There were broadly three periods during which public open space was created in Tower Hamlets. These moves were primarily to benefit people, rather than improve land or rental values. The first was the deliberate creation of Victoria Park in the mid 19 th century, the late 19 th century saw the conversion of churchyards to public gardens and the most recent was in the mid 20 th century after World War 2. Various open spaces are the result of late 18 th and 19 th century urban design, being planned formal gardens set in London Squares. As such they are protected by the London Squares Preservation Act, 1931. These sites include Trinity Square Gardens , Arbour Square , Albert Gardens and the little known Oval in Bethnal Green. See full list of protected London Squares below. Many churchyards, particularly in the west of borough became public open spaces managed by the local authority. Having been closed to further burial use because they were overflowing, they were converted in the second half of the 19 th century into public gardens.