Janet K. Ruffing a Path to God Today Mediated Through Visionary Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

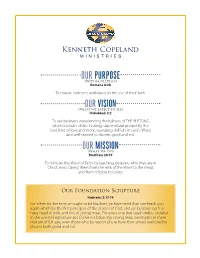

2018 KCM Purpose Vision Mission Statement.Indd

OUR PURPOSE (Why KCM Exists) Romans 8:28 To mature believers worldwide in the use of their faith. OUR VISION (What We Expect to See) Habakkuk 2:2 To see believers experiencing the fullness of THE BLESSING which includes divine healing, supernatural prosperity, the God kind of love and more; operating skillfully in God’s Word; and well-trained to discern good and evil. OUR MISSION (What We Do) Matthew 28:19 To minister the Word of Faith, by teaching believers who they are in Christ Jesus; taking them from the milk of the Word to the meat, and from religion to reality. Our Foundation Scripture Hebrews 5:12-14 For when for the time ye ought to be teachers, ye have need that one teach you again which be the first principles of the oracles of God; and are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat. For every one that useth milk is unskilful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil. STATEMENT OF FAITH • We believe in one God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Creator of all things. • We believe that the Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, was conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, was crucified, died and was buried; He was resurrected, ascended into heaven and is now seated at the right hand of God the Father and is true God and true man. -

Speaking in Tongues

SPEAKING IN TONGUES “He who speaks in a tongue edifies himself” 1 Corinthians 14:4a Grace Christian Center 200 Olympic Place Pastor Kevin Hunter Port Ludlow, WA 8365 360 821 9680 mailing | 290 Olympus Boulevard Pastor Sherri Barden Port Ludlow, WA 98365 360 821 9684 Pastor Karl Barden www.GraceChristianCenter.us 360 821 9667 Our Special Thanks for the Contributions of Living Faith Fellowship Pastor Duane J. Fister Pastor Karl A. Barden Pastor Kevin O. Hunter For further information and study, one of the best resources for answering questions and dealing with controversies about the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the gift of speaking in tongues is You Shall Receive Power by Dr. Graham Truscott. This book is available for purchase in Shiloh Bookstore or for check-out in our library. © 1996 Living Faith Publications. All rights reserved. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Unless otherwise identified, scripture quotations are from The New King James Version of the Bible, © 1982, Thomas Nelson Inc., Publishers. IS SPEAKING IN TONGUES A MODERN PHENOMENON? No, though in the early 1900s there indeed began a spiritual movement of speaking in tongues that is now global in proportion. Speaking in tongues is definitely a gift for today. However, until the twentieth century, speaking in tongues was a commonly occurring but relatively unpublicized inclusion of New Testament Christianity. Many great Christians including Justin Martyr, Iranaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Augustine, Chrysostom, Luther, Wesley, Finney, Moody, etc., either experienced the gift themselves or attested to it. Prior to 1800, speaking in tongues had been witnessed among the Huguenots, the Camisards, the Quakers, the Shakers, and early Methodists. -

To Serve God... Religious Recognitions Created by the Faith Communities for Their Members Who Are Girl Scouts

TO SERVE GOD... RELIGIOUS RECOGNITIONS CREATED BY THE FAITH COMMUNITIES FOR THEIR MEMBERS WHO ARE GIRL SCOUTS African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Anglican Church in North America Baha’i God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life St. George Cross Unity of Mankind Unity of Mankind Unity of Mankind Service to Humanity Baptist Buddhist Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life Good Shepherd Padma Padma God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service Christian Methodist Episcopal (C.M.E.) Christian Science Churches of Christ God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service God and Country God and Country Loving Servant Joyful Servant Good Servant Giving Servant Faithful Servant Church of the Nazarene Community of Christ Eastern Orthodox God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service Light of Path of Exploring Community World Community St. George Chi-Rho Alpha Omega Prophet Elias the World the Disciple Together International Youth Service Episcopal Hindu Islamic God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life St. George Dharma Karma Bismillah In the Name of Allah Quratula’in Muslimeen Jewish Lutheran (Mormon) Church of Jesus Polish National Catholic Church Lehavah Bat Or Menorah Or Emunah Ora God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life Lamb Christ of Latter-day Saints Love of God God and Community Bishop Thaddeus F. -

Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, B. (2005). Daniels, B. (2005). Nondualism and the divine domain. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24(1), 1–15.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2005.24.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels This paper claims that the ultimate issue confronting transpersonal theory is that of nondual- ism. The revelation of this spiritual reality has a long history in the spiritual traditions, which has been perhaps most prolifically advocated by Ken Wilber (1995, 2000a), and fully explicat- ed by David Loy (1998). Nonetheless, these scholarly accounts of nondual reality, and the spir- itual traditions upon which they are based, either do not include or else misrepresent the reve- lation of a contemporary spiritual master crucial to the understanding of nondualism. Avatar Adi Da not only offers a greater differentiation of nondual reality than can be found in contem- porary scholarly texts, but also a dimension of nondualism not found in any previous spiritual revelation. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

Symbolism of Surface and Depth in Edvard

MARJA LAHELMA want life and its terrible depths, its bottomless abyss. to hold on to the ideal, and the other that is at the same Lure of the Abyss: – Stanisław Przybyszewski1 time ripping it apart. This article reflects on this more general issue through Symbolist artists sought unity in the Romantic spirit analysis and discussion of a specific work of art, the paint- Symbolism of Ibut at the same time they were often painfully aware of the ing Vision (1892) by Edvard Munch. This unconventional impossibility of attaining it by means of a material work of self-portrait represents a distorted human head floating in art. Their aesthetic thinking has typically been associated water. Peacefully gliding above it is a white swan – a motif Surface and with an idealistic perspective that separates existence into that is laden with symbolism alluding to the mysteries of two levels: the world of appearances and the truly existing life and death, beauty, grace, truth, divinity, and poetry. The Depth in Edvard realm that is either beyond the visible world or completely swan clearly embodies something that is pure and beautiful separated from it. The most important aim of Symbolist art as opposed to the hideousness of the disintegrating head. would then be to establish a direct contact with the immate- The head separated from the body may be seen as a refer- Munch’s Vision rial and immutable realm of the spirit. However, in addition ence to a dualistic vision of man, and an attempt to separate to this idealistic tendency, the culture of the fin-de-siècle the immaterial part, the soul or the spirit, from the material (1892) also contained a disintegrating penchant which found body. -

Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms?

Quaker Religious Thought Volume 118 Article 2 1-1-2012 Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms? Paul Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Paul (2012) "Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms?," Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 118 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol118/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Religious Thought by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS “NONTHEIST QUAKERISM” A CONTRADICTION OF TERMS? Paul anderson s the term “Nontheist Friends” a contradiction of terms? On one Ihand, Friends have been free-thinking and open theologically, so liberal Friends have tended to welcome almost any nonconventional trend among their members. As a result, atheists and nontheists have felt a welcome among them, and some Friends in Britain and Friends General Conference have recently explored alternatives to theism. On the other hand, what does it mean to be a “Quaker”—even among liberal Friends? Can an atheist claim with integrity to be a “birthright Friend” if one has abandoned faith in the God, when the historic heart and soul of the Quaker movement has diminished all else in service to a dynamic relationship with the Living God? And, can a true nontheist claim to be a “convinced Friend” if one declares being unconvinced of God’s truth? On the surface it appears that one cannot have it both ways. -

The Philosophy of Religion Contents

The Philosophy of Religion Course notes by Richard Baron This document is available at www.rbphilo.com/coursenotes Contents Page Introduction to the philosophy of religion 2 Can we show that God exists? 3 Can we show that God does not exist? 6 If there is a God, why do bad things happen to good people? 8 Should we approach religious claims like other factual claims? 10 Is being religious a matter of believing certain factual claims? 13 Is religion a good basis for ethics? 14 1 Introduction to the philosophy of religion Why study the philosophy of religion? If you are religious: to deepen your understanding of your religion; to help you to apply your religion to real-life problems. Whether or not you are religious: to understand important strands in our cultural history; to understand one of the foundations of modern ethical debate; to see the origins of types of philosophical argument that get used elsewhere. The scope of the subject We shall focus on the philosophy of religions like Christianity, Islam and Judaism. Other religions can be quite different in nature, and can raise different questions. The questions in the contents list indicate the scope of the subject. Reading You do not need to do extra reading, but if you would like to do so, you could try either one of these two books: Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford University Press, third edition, 2003. Chad Meister, Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Routledge, 2009. 2 Can we show that God exists? What sorts of demonstration are there? Proofs in the strict sense: logical and mathematical proof Demonstrations based on external evidence Demonstrations based on inner experience How strong are these different sorts of demonstration? Which ones could other people reject, and on what grounds? What sort of thing could have its existence shown in each of these ways? What might we want to show? That God exists That it is reasonable to believe that God exists The ontological argument Greek onta, things that exist. -

The Story of God, the Story of Us: Study Guide for Group Discussion

Study Guide for Group Discussion to Sean Gladding’s The Story of God, The Story of Us Written by Michele Arndt An imprint of InterVarsity Press Downers Grove, Illinois Copyright ©2014 by InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA. All rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted to reproduce this work electronically or in print for purposes of individual study or group discussion of Sean Gladding’s The Story of God, The Story of Us. Any other use of this work requires written permission from InterVarsity Press by writing [email protected] or: Permissions InterVarsity Press P.O. Box 1400 Downers Grove, IL 60515 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – Creation 2 Chapter 2 – Catastrophe 4 Chapter 3 – Covenant 5 Chapter 4 – Community 7 Chapter 5 – Community Part II 9 Chapter 6 – Conquest 13 Chapter 7 – Crown 15 Chapter 8– Conceit 17 Chapter 9– Christ 19 Chapter 10– Cross 23 Chapter 11– Church 25 Chapter 12– Consummation 28 Table of Themes 30 About Michele Arndt Michele Arndt is a campus staff member for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA at the University of Wisconsin—River Falls. She studied broadcast journalism at the University of Northwestern in St. Paul, Minnesota. The Story of God, Story of Us – by Sean Gladding A Study Guide Welcome to “The Story of God, The Story of Us” This study guide has been created to help you connect the narrative from the story, one chapter at a time, to the entire bible cover to cover. It will be best used if the chapter to be discussed is read in conjunction with the scripture passages which correspond. -

Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art and Spirituality

AM 9:31 2 12/10/14 2 224926_Covers_DEC10.indd INNER VISIONS: SACRED PLANTS, ART AND SPIRITUALITY Brauer Museum of Art • Valparaiso University Vision 12: Three Types of Sorcerers Gouache on paper, 12 x 16 inches. 1989 Pablo Amaringo 224926_Covers_DEC10.indd 3 12/10/14 9:31 AM 3 224926_Text_Dec12.indd 3 12/12/14 11:42 AM Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art and Spirituality • An Exhibition of Art Presented by the Brauer Museum • Curated by Luis Eduardo Luna 4 224926_Text.indd 4 12/9/14 10:00 PM Contents 6 From the Director Gregg Hertzlieb 9 Introduction Robert Sirko 13 Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art and Spirituality Luis Eduardo Luna 29 Encountering Other Worlds, Amazonian and Biblical Richard E. DeMaris 35 The Artist and the Shaman: Seen and Unseen Worlds Robert Sirko 73 Exhibition Listing 5 224926_Text.indd 5 12/9/14 10:00 PM From the Director In this Brauer Museum of Art exhibition and accompanying other than earthly existence. Additionally, while some objects publication, expertly curated by the noted scholar Luis Eduardo may be culture specific in their references and nature, they are Luna, we explore the complex and enigmatic topic of the also broadly influential on many levels to, say, contemporary ritual use of sacred plants to achieve visionary states of mind. American and European subcultures, as well as to contemporary Working as a team, Luna, Valparaiso University Associate artistic practices in general. Professor of Art Robert Sirko, Valparaiso University Professor We at the Brauer Museum of Art wish to thank the Richard E. DeMaris and the Brauer Museum staff present following individuals and agencies for making this exhibition our efforts of examining visual products arising from the possible: the Brauer Museum of Art’s Brauer Endowment, ingestion of these sacred plants and brews such as ayahuasca. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 80:3–4 July/October 2016 Table of Contents Forty Years after Seminex: Reflections on Social and Theological Factors Leading to the Walkout Lawrence R. Rast Jr. ......................................................................... 195 Satis est: AC VII as the Hermeneutical Key to the Augsburg Confession Albert B. Collver ............................................................................... 217 Slaves to God, Slaves to One Another: Testing an Idea Biblically John G. Nordling .............................................................................. 231 Waiting and Waiters: Isaiah 30:18 in Light of the Motif of Human Waiting in Isaiah 8 and 25 Ryan M. Tietz .................................................................................... 251 Michael as Christ in the Lutheran Exegetical Tradition: An Analysis Christian A. Preus ............................................................................ 257 Justification: Set Up Where It Ought Not to Be David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 269 Culture and the Vocation of the Theologian Roland Ziegler .................................................................................. 287 American Lutherans and the Problem of Pre-World War II Germany John P. Hellwege, Jr. .......................................................................... 309 Research Notes ............................................................................................... 333 The Gospel -

All About Speaking in Tongues Fernand Legrand “Le Signal” CH-1326 – Juriens Switzerland Phone: 024.453.14.47 Source

All About Speaking in Tongues Fernand Legrand “Le Signal” CH-1326 – Juriens Switzerland Phone: 024.453.14.47 Source: http://www.seefrance.net/tongues.html Contents PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1 – ANALYSIS OF THE CHARISMATIC RENEWAL .................................................... 5 CHAPTER 2 – A MESSAGE TO MEN? ............................................................................................. 9 Scriptural Pattern? ......................................................................................................................... 9 Prevented from Seeing ................................................................................................................. 10 Scriptural Verification ................................................................................................................. 12 Papering over the cracks .............................................................................................................. 14 CHAPTER 3 – A SIGN FOR BELIEVERS? ..................................................................................... 15 The Unbelievers’ Identity ............................................................................................................ 16 The Analogy of Faith .................................................................................................................... 18 Superiority Complex ...................................................................................................................