Master Document Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illt3/F£ ( /*- Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Uhu I I I996 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NAT. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Bullard, Casiville House___________________________________ other names/site number N/A. 2. Location street & number 1282 Folsom Street D not for publication N/A city or town __ St. Paul, _ D vicinity N/A state Minnesota code MN county Ramsey code _ zip code 55117 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this EsD nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Histpric' Places and me(£ts-*he-piocedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property Bmeets C Sdoes notVmeeytfe National Registe , criteria. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Minnesota in Profile

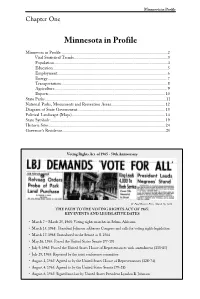

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

The Minnesota State Capitol a 1905 Masterpiece Restored to Its Original Grandeur

The Minnesota State Capitol A 1905 masterpiece restored to its original grandeur Denis Gardner onstruction of the Minnesota State Capitol in St. capitol—including actual festoons—paying overt def- Paul began early in 1896. The immense under- erence to the Renaissance palazzo. Fluted columns with taking was completed nine years later. This was ornate capitals are adjacent to immense Roman arches notC the state’s first capitol building. The initial attempt, at accented with scrolled keystones. Six sculpted figures Tenth and Cedar Streets, was completed in 1853 as the ter- symbolic of humankind’s better qualities adorned the ritorial capitol, and it continued as the seat of Minnesota’s entablature over the portico, upon which gleamed the government with statehood in 1858. After two expan- quadriga of golden horses—The Progress of the State sculp- sions, in 1874 and 1878, the pedestrian Greek revival–style ture created by Daniel Chester French and Edward C. statehouse was consumed by fire. It was replaced with a Potter. Paired columns encircled the richly ornamented new building on the same site in 1882. While also featur- dome, supporting a cornice bearing raptors, while window ing classical architectural elements, the second capitol openings featured pediments and scrolled hoods framed building had a Victorian air. Almost from the time it was within recessed panels parceled by the dome’s vertical erected, it was thought too small for the state’s business. ribbing. The final garnish on this architectural confection With the third building, Minnesota finally got it right. was a lantern with shining, globed finial. A marvelous Renaissance monument in the Beaux-Arts The capitol’s interior was even more classically exu- tradition, the elegant design was the handiwork of St. -

2013 MNHS Legacy Report (PDF)

Minnesota History: Building A Legacy JAnuAry 2013 | Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director and CEO . 1 Introduction . 2 Feature Stories on FY12–13 History Programs, Partnerships, Grants and Initiatives Then Now Wow Exhibit . 7 Civil War Commemoration . 9 U .S .-Dakota War of 1862 Commemoration . 10 Statewide History Programs . 12 Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants Highlights . 14 Archaeological Surveys . 16 Minnesota Digital Library . 17 FY12–13 ACHF History Appropriations Language . Grants tab FY12–13 Report of Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 19 FY12–13 Report of Statewide History Programs . 57 FY12–13 Report of Statewide History Partnerships . 73 FY12–13 Report of Other Statewide Initiatives Surveys of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 85 Minnesota Digital Library . 86 Civil War Commemoration . 87 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $6,413 Upon request this report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of this report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2012 report is available at the Society’s website: legacy.mnhs.org. COVER IMAGE: Kids try plowing at the Oliver H. Kelley Farm in Elk River, June 2012 Letter from the Director and CEO January 15, 2013 As we near the close of the second biennium since the passage of the Legacy Amendment in November 2008, Minnesotans are preserving our past, sharing our state’s stories and connecting to history like never before. -

Business Directory

Business Directory 7 Steakhouse & Sushi 700 Hennepin Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55403 Phone: 612.238.7777 Fax: 612-746.1607 Website: http://7mpls.net/ We will provide a truly memorable dining experience through serving fresh, innovative, healthy foods using only the finest ingredients paired with professional and friendly service. Seven Steakhouse embodies the classic American steakhouse with a renewed elegance. Guests delight in our careful selection of choice steak, fresh seafood, and the near intimidating selection of wine from our two-story cellar. Seven Sushi is well known for imaginative creations as well as classic favorites, contemporary sushi with new wave Asian inspired dishes. With a modern warm atmosphere, Seven is perfect for special occasions, business affairs, or just a night out. 8th Street Grill 800 Marquette Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55402 Phone: 612.349.5717 Fax: 612.349.5727 Website: www.8thstreetgrillmn.com Lunch and dinner served daily. Full bar, patio seating and free Wi-Fi available to guests. Kitchen open until 1:00am Monday through Saturday and 10:00pm Sundays. Breakfast served Saturday and Sunday mornings. AC Hotel by Marriott 401 Hennepin Ave. Minneapolis , MN 55402 Phone: 303-405-8391 Fax: Website: AccessAbility 360 Hoover Street NE Minneapolis, MN 55413 Phone: 612-331-5958 Fax: 612-331-2448 Website: www.accessability.org ACE Catering 275 Market Street Minneapolis, MN 55405 Phone: 612-238-4016 Fax: 612-238-4040 Website: http://www.damicocatering.com/ace/ Atrium Culinary Express (ACE) provides drop-off service of D'Amico quality lunches, salads, desserts and hor d'oeuvres. Orders must be received 24-72 hours in advance. -

BB2019 Ind Book.Indb

Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Maps ............................................................................................................14 -

Minnesota Historical Excursion

Minnesota Historical Excursion DAY 1 Enjoy breakfast at your Bloomington hotel, and then begin your day in Saint Paul to experience some of the Minnesota Historical Society’s historic sites and museums in the city. Begin your historical adventure at the Minnesota State Capitol. Open in 1905, the Minnesota State Capitol building is hailed as one of America’s grandest and most beautiful public buildings. While in the building, see the Minnesota Senate, House & Supreme Court chambers, Civil War & Spanish‐American War flags and arts and memorial monuments throughout the Capitol Mall. Guided tours are available hourly and are FREE. See if there are any special events taking place during your visit at www.mnhs.org/statecapitol. In very close proximity to the State Capitol building visitors will find the Minnesota History Center. This interactive museum hosts both permanent and changing exhibits, plus special programs. Signature exhibits include Minnesota's Greatest Generation, Weather Permitting and Grainland. Along with these displays, visitors will find history learning stations and history performers and two gift shops full of Minnesota treasures to remember your visit to Saint Paul. See the museum at www.mnhs.org/historyceter. Grab a bite to eat at one of Saint Paul’s great diners, cafes or taverns. From lunch, head over to the James J. Hill House. A 36,000‐square‐foot Gilded Age mansion built by a railroad entrepreneur, the house features original stained glass, woodwork and chandeliers throughout the home. A guided tour of all four floors is available. See the home in all its grandeur at www.mnhs.org/hillhouse. -

About Historic Saint Paul

About Historic Saint Paul Historic Saint Paul is a nonprofit working tostrengthen Saint Paul neighborhoods by preserving and promoting their cultural heritage and character. We have been around more than twenty years. We work in partnership with private property owners, community organizations, and public agencies to leverage Saint Paul’s cultural and historic resources as assets in economic development and community building initiatives. Round 1 1. Where did Theodore Roosevelt make his famous “speak softly and carry a big stick” speech, in 1901? A. University of Minnesota B. Minnesota State Fair C. Macalester College D. Minnesota State Capitol 2. When did attendance for the Great Minnesota Get-Together top one million visitors for the first time? A. 2011 B. 1955 C. 1990 D. 1930 3. The State Fair was originally a traveling show, finally settling in its current location in 1885. What was the name of this area? A. Saint Paul B. Falcon Heights C. Hamline D. Lauderdale 4. What is the oldest food concession on the fairgrounds? A. Tom Thumb Donuts B. Sweet Martha’s Cookie Jar C. Minnesota Dairy D. Hamline Church Dining Hall Bonus point: Name the oldest amusement! 5. In 1995, the state’s largest naturalization ceremony took place at the State Fair bandstand. How many citizens were sworn in? A. 800 B. 1,001 C. 294 D. 478 6. The Rondo neighborhood ran roughly between University Avenue to the north, Selby Avenue to the south, Rice Street to the east, and Lexington Avenue to the west. From the beginning (as early as the 1850’s), Rondo was a haven for people of color and immigrants. -

Phase Ii Architectural History Investigation for the Proposed Central Transit Corridor, Hennepin and Ramsey Counties, Minnesota

PHASE II ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY INVESTIGATION FOR THE PROPOSED CENTRAL TRANSIT CORRIDOR, HENNEPIN AND RAMSEY COUNTIES, MINNESOTA Submitted to: Ramsey County Regional Railroad Authority Submitted by: The 106 Group Ltd. September 2004 PHASE II ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY INVESTIGATION FOR THE PROPOSED CENTRAL TRANSIT CORRIDOR, HENNEPIN AND RAMSEY COUNTIES, MINNESOTA SHPO File No. 96-0059PA The 106 Group Project No. 02-34 Submitted to: Ramsey County Regional Railroad Authority 665 Ramsey County Government Center West 50 West Kellogg Boulevard St. Paul, MN 55102 Submitted by: The 106 Group Ltd. The Dacotah Building 370 Selby Avenue St. Paul, MN 55102 Project Manager: Anne Ketz, M.A., RPA Principal Investigator Betsy H. Bradley, Ph.D. Report Authors Betsy H. Bradley, Ph.D. Jennifer L. Bring, B.A. Andrea Vermeer, M.A., RPA September 2004 Central Transit Corridor Phase II Architectural History Investigation Page i MANAGEMENT SUMMARY From May to August of 2004, The 106 Group Ltd. (The 106 Group) conducted a Phase II architectural history investigation for the Central Transit Corridor (Central Corridor) project in Minneapolis, Hennepin County, and St. Paul, Ramsey County, Minnesota. The proposed project is a multi-agency undertaking being led by the Ramsey County Regional Railroad Authority (RCRRA). The Phase II investigation was conducted under contract with the RCRRA. The proposed action is a Light Rail Transit (LRT) or Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) facility for the Central Corridor, a transportation corridor that extends approximately 11 miles between downtown Minneapolis and downtown St. Paul, Minnesota. The project will be receiving federal permitting and funding, along with state funding, and, therefore, must comply with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, and with applicable state laws. -

Chapter 138 Minnesota Statutes 1978

MINNESOTA STATUTES 1978 2219 HISTORICAL SOCIETIES; HISTORIC SITES 138.02 CHAPTER 138 HISTORICAL SOCIETIES; HISTORIC SITES; ARCHIVES; FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY Sec. HISTORICAL SOCIETIES 13M1 Penalties. 138.01 Minnesota state historical society 138.42 Title. agency of state government. HISTORIC SITES ACT OF 1965 138.02 Minnesota war records commission dis 138.51 Policy. continued. 138.52 Definitions. 138.025 Transfer of control of certain historic 138.53 State historic sites, registry. sites. 138.55 State historic sites; registry, state 138.03 Custodian of records. owned lands administered by the de 138.035 State historical society authorized to partment of natural resources. support the science museum of Minne 138.56 State historic sites; registry, lands sota. owned by the cities and counties of 138.051 County historical societies. Minnesota. 138.052 Tax levy. 138.57 State historic sites; registry, federally 138.053 County historical society; tax levy; cit owned lands. ies or towns. 138.58 State historic sites; registry, privately 138.054 Minnesota history and government owned lands. learning center. 138.585 State monuments. HISTORIC SITES 138.59 Notice to Minnesota Historical Society 138.081 Executive council as agency to accept of land acquisition. federal funds. 138.60 Duties of the state and governmental 138.09 County boards may acquire historic subdivisions in regard to state historic sites. sites; prohibitions. ARCHIVES 138.61 Cooperation. 138.161 Abolition of state archives commission; 138.62 Minnesota historic sites, changes. transfer of duties. 138.63 Citation, the Minnesota historic sites 138.163 Preservation and disposal of public rec act of 1965. ords. 138.64 Contracts authorized.