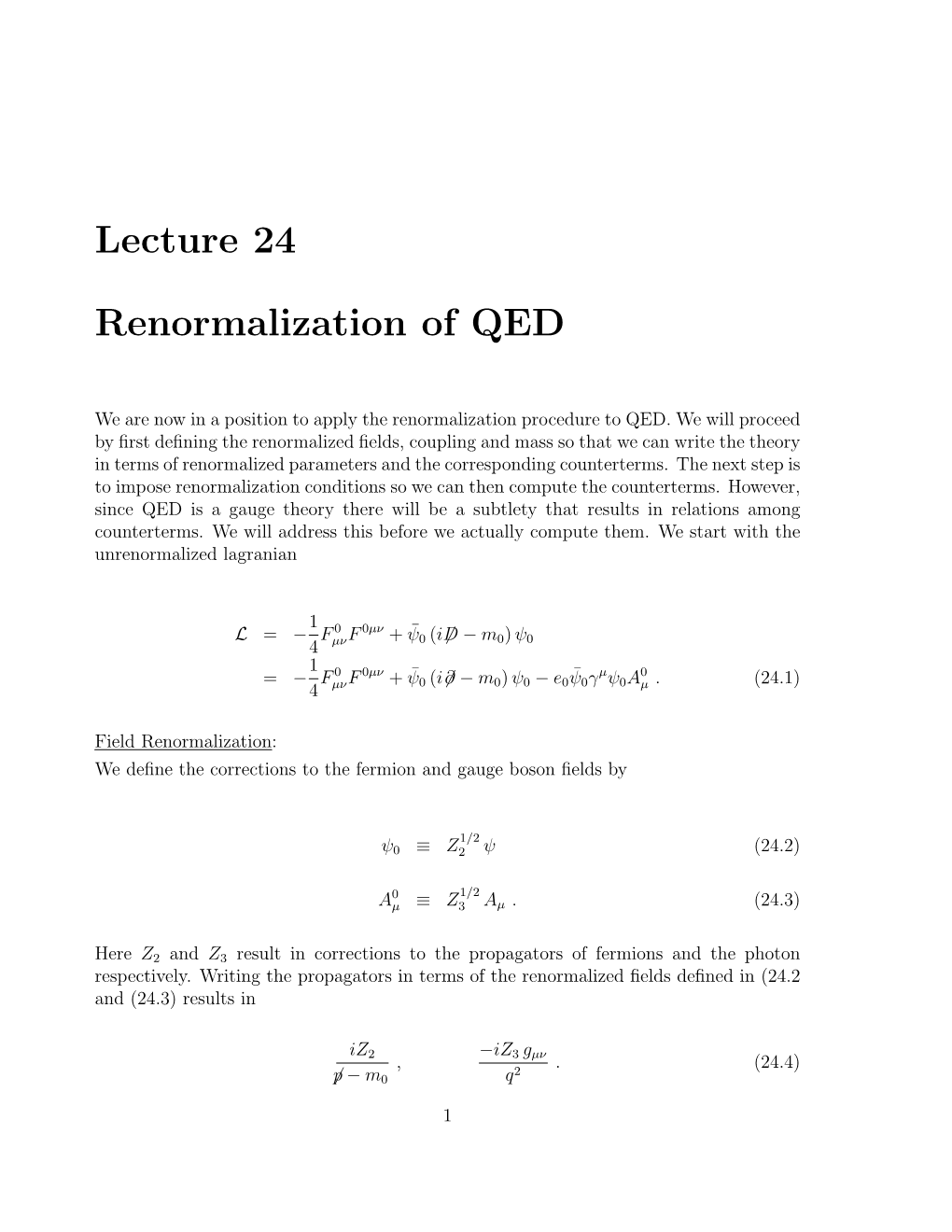

Lecture 24 Renormalization Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics

Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics Dennis V. Perepelitsa MIT Department of Physics 70 Amherst Ave. Cambridge, MA 02142 Abstract We present the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics and demon- strate its equivalence to the Schr¨odinger picture. We apply the method to the free particle and quantum harmonic oscillator, investigate the Euclidean path integral, and discuss other applications. 1 Introduction A fundamental question in quantum mechanics is how does the state of a particle evolve with time? That is, the determination the time-evolution ψ(t) of some initial | i state ψ(t ) . Quantum mechanics is fully predictive [3] in the sense that initial | 0 i conditions and knowledge of the potential occupied by the particle is enough to fully specify the state of the particle for all future times.1 In the early twentieth century, Erwin Schr¨odinger derived an equation specifies how the instantaneous change in the wavefunction d ψ(t) depends on the system dt | i inhabited by the state in the form of the Hamiltonian. In this formulation, the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian play an important role, since their time-evolution is easy to calculate (i.e. they are stationary). A well-established method of solution, after the entire eigenspectrum of Hˆ is known, is to decompose the initial state into this eigenbasis, apply time evolution to each and then reassemble the eigenstates. That is, 1In the analysis below, we consider only the position of a particle, and not any other quantum property such as spin. 2 D.V. Perepelitsa n=∞ ψ(t) = exp [ iE t/~] n ψ(t ) n (1) | i − n h | 0 i| i n=0 X This (Hamiltonian) formulation works in many cases. -

Effective Quantum Field Theories Thomas Mannel Theoretical Physics I (Particle Physics) University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany

Generating Functionals Functional Integration Renormalization Introduction to Effective Quantum Field Theories Thomas Mannel Theoretical Physics I (Particle Physics) University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany 2nd Autumn School on High Energy Physics and Quantum Field Theory Yerevan, Armenia, 6-10 October, 2014 T. Mannel, Siegen University Effective Quantum Field Theories: Lecture 1 Generating Functionals Functional Integration Renormalization Overview Lecture 1: Basics of Quantum Field Theory Generating Functionals Functional Integration Perturbation Theory Renormalization Lecture 2: Effective Field Thoeries Effective Actions Effective Lagrangians Identifying relevant degrees of freedom Renormalization and Renormalization Group T. Mannel, Siegen University Effective Quantum Field Theories: Lecture 1 Generating Functionals Functional Integration Renormalization Lecture 3: Examples @ work From Standard Model to Fermi Theory From QCD to Heavy Quark Effective Theory From QCD to Chiral Perturbation Theory From New Physics to the Standard Model Lecture 4: Limitations: When Effective Field Theories become ineffective Dispersion theory and effective field theory Bound Systems of Quarks and anomalous thresholds When quarks are needed in QCD É. T. Mannel, Siegen University Effective Quantum Field Theories: Lecture 1 Generating Functionals Functional Integration Renormalization Lecture 1: Basics of Quantum Field Theory Thomas Mannel Theoretische Physik I, Universität Siegen f q f et Yerevan, October 2014 T. Mannel, Siegen University Effective Quantum -

5 the Dirac Equation and Spinors

5 The Dirac Equation and Spinors In this section we develop the appropriate wavefunctions for fundamental fermions and bosons. 5.1 Notation Review The three dimension differential operator is : ∂ ∂ ∂ = , , (5.1) ∂x ∂y ∂z We can generalise this to four dimensions ∂µ: 1 ∂ ∂ ∂ ∂ ∂ = , , , (5.2) µ c ∂t ∂x ∂y ∂z 5.2 The Schr¨odinger Equation First consider a classical non-relativistic particle of mass m in a potential U. The energy-momentum relationship is: p2 E = + U (5.3) 2m we can substitute the differential operators: ∂ Eˆ i pˆ i (5.4) → ∂t →− to obtain the non-relativistic Schr¨odinger Equation (with = 1): ∂ψ 1 i = 2 + U ψ (5.5) ∂t −2m For U = 0, the free particle solutions are: iEt ψ(x, t) e− ψ(x) (5.6) ∝ and the probability density ρ and current j are given by: 2 i ρ = ψ(x) j = ψ∗ ψ ψ ψ∗ (5.7) | | −2m − with conservation of probability giving the continuity equation: ∂ρ + j =0, (5.8) ∂t · Or in Covariant notation: µ µ ∂µj = 0 with j =(ρ,j) (5.9) The Schr¨odinger equation is 1st order in ∂/∂t but second order in ∂/∂x. However, as we are going to be dealing with relativistic particles, space and time should be treated equally. 25 5.3 The Klein-Gordon Equation For a relativistic particle the energy-momentum relationship is: p p = p pµ = E2 p 2 = m2 (5.10) · µ − | | Substituting the equation (5.4), leads to the relativistic Klein-Gordon equation: ∂2 + 2 ψ = m2ψ (5.11) −∂t2 The free particle solutions are plane waves: ip x i(Et p x) ψ e− · = e− − · (5.12) ∝ The Klein-Gordon equation successfully describes spin 0 particles in relativistic quan- tum field theory. -

TASI 2008 Lectures: Introduction to Supersymmetry And

TASI 2008 Lectures: Introduction to Supersymmetry and Supersymmetry Breaking Yuri Shirman Department of Physics and Astronomy University of California, Irvine, CA 92697. [email protected] Abstract These lectures, presented at TASI 08 school, provide an introduction to supersymmetry and supersymmetry breaking. We present basic formalism of supersymmetry, super- symmetric non-renormalization theorems, and summarize non-perturbative dynamics of supersymmetric QCD. We then turn to discussion of tree level, non-perturbative, and metastable supersymmetry breaking. We introduce Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model and discuss soft parameters in the Lagrangian. Finally we discuss several mech- anisms for communicating the supersymmetry breaking between the hidden and visible sectors. arXiv:0907.0039v1 [hep-ph] 1 Jul 2009 Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Motivation..................................... 2 1.2 Weylfermions................................... 4 1.3 Afirstlookatsupersymmetry . .. 5 2 Constructing supersymmetric Lagrangians 6 2.1 Wess-ZuminoModel ............................... 6 2.2 Superfieldformalism .............................. 8 2.3 VectorSuperfield ................................. 12 2.4 Supersymmetric U(1)gaugetheory ....................... 13 2.5 Non-abeliangaugetheory . .. 15 3 Non-renormalization theorems 16 3.1 R-symmetry.................................... 17 3.2 Superpotentialterms . .. .. .. 17 3.3 Gaugecouplingrenormalization . ..... 19 3.4 D-termrenormalization. ... 20 4 Non-perturbative dynamics in SUSY QCD 20 4.1 Affleck-Dine-Seiberg -

Renormalization and Effective Field Theory

Mathematical Surveys and Monographs Volume 170 Renormalization and Effective Field Theory Kevin Costello American Mathematical Society surv-170-costello-cov.indd 1 1/28/11 8:15 AM http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/surv/170 Renormalization and Effective Field Theory Mathematical Surveys and Monographs Volume 170 Renormalization and Effective Field Theory Kevin Costello American Mathematical Society Providence, Rhode Island EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Ralph L. Cohen, Chair MichaelA.Singer Eric M. Friedlander Benjamin Sudakov MichaelI.Weinstein 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 81T13, 81T15, 81T17, 81T18, 81T20, 81T70. The author was partially supported by NSF grant 0706954 and an Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/surv-170 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Costello, Kevin. Renormalization and effective fieldtheory/KevinCostello. p. cm. — (Mathematical surveys and monographs ; v. 170) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8218-5288-0 (alk. paper) 1. Renormalization (Physics) 2. Quantum field theory. I. Title. QC174.17.R46C67 2011 530.143—dc22 2010047463 Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy a chapter for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in reviews, provided the customary acknowledgment of the source is given. Republication, systematic copying, or multiple reproduction of any material in this publication is permitted only under license from the American Mathematical Society. Requests for such permission should be addressed to the Acquisitions Department, American Mathematical Society, 201 Charles Street, Providence, Rhode Island 02904-2294 USA. -

Regularization and Renormalization of Non-Perturbative Quantum Electrodynamics Via the Dyson-Schwinger Equations

University of Adelaide School of Chemistry and Physics Doctor of Philosophy Regularization and Renormalization of Non-Perturbative Quantum Electrodynamics via the Dyson-Schwinger Equations by Tom Sizer Supervisors: Professor A. G. Williams and Dr A. Kızılers¨u March 2014 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction................................... 1 1.2 Dyson-SchwingerEquations . .. .. 2 1.3 Renormalization................................. 4 1.4 Dynamical Chiral Symmetry Breaking . 5 1.5 ChapterOutline................................. 5 1.6 Notation..................................... 7 2 Canonical QED 9 2.1 Canonically Quantized QED . 9 2.2 FeynmanRules ................................. 12 2.3 Analysis of Divergences & Weinberg’s Theorem . 14 2.4 ElectronPropagatorandSelf-Energy . 17 2.5 PhotonPropagatorandPolarizationTensor . 18 2.6 ProperVertex.................................. 20 2.7 Ward-TakahashiIdentity . 21 2.8 Skeleton Expansion and Dyson-Schwinger Equations . 22 2.9 Renormalization................................. 25 2.10 RenormalizedPerturbationTheory . 27 2.11 Outline Proof of Renormalizability of QED . 28 3 Functional QED 31 3.1 FullGreen’sFunctions ............................. 31 3.2 GeneratingFunctionals............................. 33 3.3 AbstractDyson-SchwingerEquations . 34 3.4 Connected and One-Particle Irreducible Green’s Functions . 35 3.5 Euclidean Field Theory . 39 3.6 QEDviaFunctionalIntegrals . 40 3.7 Regularization.................................. 42 3.7.1 Cutoff Regularization . 42 3.7.2 Pauli-Villars Regularization . 42 i 3.7.3 Lattice Regularization . 43 3.7.4 Dimensional Regularization . 44 3.8 RenormalizationoftheDSEs ......................... 45 3.9 RenormalizationGroup............................. 49 3.10BrokenScaleInvariance ............................ 53 4 The Choice of Vertex 55 4.1 Unrenormalized Quenched Formalism . 55 4.2 RainbowQED.................................. 57 4.2.1 Self-Energy Derivations . 58 4.2.2 Analytic Approximations . 60 4.2.3 Numerical Solutions . 62 4.3 Rainbow QED with a 4-Fermion Interaction . -

On Topological Vertex Formalism for 5-Brane Webs with O5-Plane

DIAS-STP-20-10 More on topological vertex formalism for 5-brane webs with O5-plane Hirotaka Hayashi,a Rui-Dong Zhub;c aDepartment of Physics, School of Science, Tokai University, 4-1-1 Kitakaname, Hiratsuka-shi, Kanagawa 259-1292, Japan bInstitute for Advanced Study & School of Physical Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215006, China cSchool of Theoretical Physics, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies 10 Burlington Road, Dublin, Ireland E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: We propose a concrete form of a vertex function, which we call O-vertex, for the intersection between an O5-plane and a 5-brane in the topological vertex formalism, as an extension of the work of [1]. Using the O-vertex it is possible to compute the Nekrasov partition functions of 5d theories realized on any 5-brane web diagrams with O5-planes. We apply our proposal to 5-brane webs with an O5-plane and compute the partition functions of pure SO(N) gauge theories and the pure G2 gauge theory. The obtained results agree with the results known in the literature. We also compute the partition function of the pure SU(3) gauge theory with the Chern-Simons level 9. At the end we rewrite the O-vertex in a form of a vertex operator. arXiv:2012.13303v2 [hep-th] 12 May 2021 Contents 1 Introduction1 2 O-vertex 3 2.1 Topological vertex formalism with an O5-plane3 2.2 Proposal for O-vertex6 2.3 Higgsing and O-planee 9 3 Examples 11 3.1 SO(2N) gauge theories 11 3.1.1 Pure SO(4) gauge theory 12 3.1.2 Pure SO(6) and SO(8) Theories 15 3.2 SO(2N -

Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics

Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics Emma Wikberg Project work, 4p Department of Physics Stockholm University 23rd March 2006 Abstract The method of Path Integrals (PI’s) was developed by Richard Feynman in the 1940’s. It offers an alternate way to look at quantum mechanics (QM), which is equivalent to the Schrödinger formulation. As will be seen in this project work, many "elementary" problems are much more difficult to solve using path integrals than ordinary quantum mechanics. The benefits of path integrals tend to appear more clearly while using quantum field theory (QFT) and perturbation theory. However, one big advantage of Feynman’s formulation is a more intuitive way to interpret the basic equations than in ordinary quantum mechanics. Here we give a basic introduction to the path integral formulation, start- ing from the well known quantum mechanics as formulated by Schrödinger. We show that the two formulations are equivalent and discuss the quantum mechanical interpretations of the theory, as well as the classical limit. We also perform some explicit calculations by solving the free particle and the harmonic oscillator problems using path integrals. The energy eigenvalues of the harmonic oscillator is found by exploiting the connection between path integrals, statistical mechanics and imaginary time. Contents 1 Introduction and Outline 2 1.1 Introduction . 2 1.2 Outline . 2 2 Path Integrals from ordinary Quantum Mechanics 4 2.1 The Schrödinger equation and time evolution . 4 2.2 The propagator . 6 3 Equivalence to the Schrödinger Equation 8 3.1 From the Schrödinger equation to PI’s . 8 3.2 From PI’s to the Schrödinger equation . -

Quantum Electrodynamics in Strong Magnetic Fields. 111* Electron-Photon Interactions

Aust. J. Phys., 1983, 36, 799-824 Quantum Electrodynamics in Strong Magnetic Fields. 111* Electron-Photon Interactions D. B. Melrose and A. J. Parle School of Physics, University of Sydney. Sydney, N.S.W. 2006. Abstract A version of QED is developed which allows one to treat electron-photon interactions in the magnetized vacuum exactly and which allows one to calculate the responses of a relativistic quantum electron gas and include these responses in QED. Gyromagnetic emission and related crossed processes, and Compton scattering and related processes are discussed in some detail. Existing results are corrected or generalized for nonrelativistic (quantum) gyroemission, one-photon pair creation, Compton scattering by electrons in the ground state and two-photon excitation to the first Landau level from the ground state. We also comment on maser action in one-photon pair annihilation. 1. Introduction A full synthesis of quantum electrodynamics (QED) and the classical theory of plasmas requires that the responses of the medium (plasma + vacuum) be included in the photon properties and interactions in QED and that QED be used to calculate the responses of the medium. It was shown by Melrose (1974) how this synthesis could be achieved in the unmagnetized case. In the present paper we extend the synthesized theory to include the magnetized case. Such a synthesized theory is desirable even when the effects of a material medium are negligible. The magnetized vacuum is birefringent with a full hierarchy of nonlinear response tensors, and for many purposes it is convenient to treat the magnetized vacuum as though it were a material medium. -

'Diagramology' Types of Feynman Diagram

`Diagramology' Types of Feynman Diagram Tim Evans (2nd January 2018) 1. Pieces of Diagrams Feynman diagrams1 have four types of element:- • Internal Vertices represented by a dot with some legs coming out. Each type of vertex represents one term in Hint. • Internal Edges (or legs) represented by lines between two internal vertices. Each line represents a non-zero contraction of two fields, a Feynman propagator. • External Vertices. An external vertex represents a coordinate/momentum variable which is not integrated out. Whatever the diagram represents (matrix element M, Green function G or sometimes some other mathematical object) the diagram is a function of the values linked to external vertices. Sometimes external vertices are represented by a dot or a cross. However often no explicit notation is used for an external vertex so an edge ending in space and not at a vertex with one or more other legs will normally represent an external vertex. • External Legs are ones which have at least one end at an external vertex. Note that external vertices may not have an explicit symbol so these are then legs which just end in the middle of no where. Still represents a Feynman propagator. 2. Subdiagrams A subdiagram is a subset of vertices V and all the edges between them. You may also want to include the edges connected at one end to a vertex in our chosen subset, V, but at the other end connected to another vertex or an external leg. Sometimes these edges connecting the subdiagram to the rest of the diagram are not included, in which case we have \amputated the legs" and we are working with a \truncated diagram". -

7 Quantized Free Dirac Fields

7 Quantized Free Dirac Fields 7.1 The Dirac Equation and Quantum Field Theory The Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation which describes the quantum dynamics of spinors. We will see in this section that a consistent description of this theory cannot be done outside the framework of (local) relativistic Quantum Field Theory. The Dirac Equation (i∂/ m)ψ =0 ψ¯(i∂/ + m) = 0 (1) − can be regarded as the equations of motion of a complex field ψ. Much as in the case of the scalar field, and also in close analogy to the theory of non-relativistic many particle systems discussed in the last chapter, the Dirac field is an operator which acts on a Fock space. We have already discussed that the Dirac equation also follows from a least-action-principle. Indeed the Lagrangian i µ = [ψ¯∂ψ/ (∂µψ¯)γ ψ] mψψ¯ ψ¯(i∂/ m)ψ (2) L 2 − − ≡ − has the Dirac equation for its equation of motion. Also, the momentum Πα(x) canonically conjugate to ψα(x) is ψ δ † Πα(x)= L = iψα (3) δ∂0ψα(x) Thus, they obey the equal-time Poisson Brackets ψ 3 ψα(~x), Π (~y) P B = iδαβδ (~x ~y) (4) { β } − Thus † 3 ψα(~x), ψ (~y) P B = δαβδ (~x ~y) (5) { β } − † In other words the field ψα and its adjoint ψα are a canonical pair. This result follows from the fact that the Dirac Lagrangian is first order in time derivatives. Notice that the field theory of non-relativistic many-particle systems (for both fermions on bosons) also has a Lagrangian which is first order in time derivatives. -

A Supersymmetry Primer

hep-ph/9709356 version 7, January 2016 A Supersymmetry Primer Stephen P. Martin Department of Physics, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb IL 60115 I provide a pedagogical introduction to supersymmetry. The level of discussion is aimed at readers who are familiar with the Standard Model and quantum field theory, but who have had little or no prior exposure to supersymmetry. Topics covered include: motiva- tions for supersymmetry, the construction of supersymmetric Lagrangians, superspace and superfields, soft supersymmetry-breaking interactions, the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM), R-parity and its consequences, the origins of supersymmetry breaking, the mass spectrum of the MSSM, decays of supersymmetric particles, experi- mental signals for supersymmetry, and some extensions of the minimal framework. Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Interlude: Notations and Conventions 13 3 Supersymmetric Lagrangians 17 3.1 The simplest supersymmetric model: a free chiral supermultiplet ............. 18 3.2 Interactions of chiral supermultiplets . ................ 22 3.3 Lagrangians for gauge supermultiplets . .............. 25 3.4 Supersymmetric gauge interactions . ............. 26 3.5 Summary: How to build a supersymmetricmodel . ............ 28 4 Superspace and superfields 30 4.1 Supercoordinates, general superfields, and superspace differentiation and integration . 31 4.2 Supersymmetry transformations the superspace way . ................ 33 4.3 Chiral covariant derivatives . ............ 35 4.4 Chiralsuperfields................................ ........ 37 arXiv:hep-ph/9709356v7 27 Jan 2016 4.5 Vectorsuperfields................................ ........ 38 4.6 How to make a Lagrangian in superspace . .......... 40 4.7 Superspace Lagrangians for chiral supermultiplets . ................... 41 4.8 Superspace Lagrangians for Abelian gauge theory . ................ 43 4.9 Superspace Lagrangians for general gauge theories . ................. 46 4.10 Non-renormalizable supersymmetric Lagrangians . .................. 49 4.11 R symmetries........................................