Walgreens: Strategic Evolution1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TC-017 Butterfield, Dawn (National Community Pharmacy Association)

Peter Mucchetti, Chief Healthcare and Consumer Products Section, Antitrust Division Department of Justice 450 Fifth Street NW, Suite 4100 Washington, DC 20530 December 13, 2018 Dear Judge Leon: Thank you so much for inviting or allowing comments on the proposed CVS/Aetna merger. We (pharmacy owners/pharmacists) were not happy when our own organization - NCPA - National Community Pharmacy Association was referenced in the Congressional Hearing on this merger earlier in the year that "we were fine" with the merger as expressed by Tom Moriarty - CVS General Counsel to the Congressional Committee. This most assuredly is NOT the case I can assure you. However that was communicated - and not clarified by our association is an issue we are all still highly upset about as I believe that was the time to publicly state our vehement opposition to this merger. In other words, a major ball was dropped and a bell was rung that couldn't be unrung. That being said - we, as business owners and professionals don't know how we can state our issues - which are numerous and we were being told by virtually everyone that the merger is a "done deal" as the FTC and DOJ didn't have an issue with it. I hope you receive communication from people who took the time to do so. Some people are frozen and/or feel defeated as they believe there's nothing to stop this train and have given up. I can say with certainty that for every letter from a pharmacist/pharmacy owner/pharmacy professor - there were 1000 that went along with it! I'm enclosing some material you may already have, but the infographic on the states shows to the extent of what can happen when your competition sets YOUR price. -

CVS Pharmacy Network

Participating Retail Pharmacies The following list shows the major chain pharmacies and affiliated groups of independent community pharmacies that accept your prescription benefit ID card. In addition to these, most independent pharmacies nationwide also take part in your prescription program. To find out if a pharmacy not listed here accepts your card, call the pharmacy directly. A C (continued) G (continued) A & P Pharmacy CVS Caremark Specialty Pharmacy Giant Eagle Pharmacy AAP / United Drugs CVS/Longs Giant Pharmacy Accredo Health Group, Inc. CVS/pharmacy Good Neighbor Pharmacy ACME Pharmacy Albertson’s Pharmacy American Pharmacy Cooperative / D H American Pharmacy Network Solutions Dahl’s Pharmacy Haggen Pharmacy American Home Patient Dierbergs Pharmacy Hannaford Food & Drug American Pharmacy Dillon Pharmacy Happy Harry’s Ameridrug Pharmacy Discount Drug Mart Harmons Pharmacy Apria Healthcare, Inc. Doc’s Drugs Harps Pharmacy Doctor’s Choice Pharmacy Aurora Pharmacy Harris Teeter Pharmacy Dominick’s Pharmacy Harvard Drug Drug Town Pharmacy Harvard Vanguard Medical Association B Drug Warehouse Harveys Supermarket Pharmacy Baker’s Pharmacy Drug World H-E-B Pharmacy Bartell Drugs Drugs for Less Health Mart Basha’s United Drug Duane Reade HealthPartners Bel Air Pharmacy Duluth Clinic Hen House Pharmacy Bi-Lo Pharmacy Henry Ford Pharmacy Bi-Mart Pharmacy Hi-School Pharmacies Biggs Pharmacy E Hilander Pharmacy Bioscrip Pharmacy EPIC Homeland Pharmacy Bloom Pharmacy Eaton Apothecary Horton & Converse Brookshire Brothers Pharmacy Econofoods -

Pharmacies Located in North Carolina

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Limited Network: Pharmacies Located in North Carolina Pharmacy Name Address City State Zip Phone Number 1ST RX PHARMACY 837 N CENTER ST STATESVILLE NC 28677 7048720880 1ST RX PHARMACY INC- GREENBRIAR 308-A MOCKSVILLE HWY STATESVILLE NC 28625 7048786225 A1 PHARMACY AND SURGICAL SUPPLY LLC 124 FOREST HILL RD LEXINGTON NC 27295 3362246500 A2Z HEALTHMART PHARMACY 1408 ARCHDALE DR CHARLOTTE NC 28210 9803550906 ABERDEEN PRESCRIPTION SHOPPE 1389 N SANDHILLS BLVD ABERDEEN NC 28315 9109441313 ADDICTION RECOVERY MEDICAL SERVICES 536 SIGNAL HILL DRIVE EXT STATESVILLE NC 28625 7048181117 ADULT CLINIC AND GERIATRIC CENTER A 25 OFFICE PARK DRIVE JACKSONVILLE NC 28546 9103534878 ADVANCED HOME CARE 4001 PIEDMONT PKWY GREENSBORO NC 27265 3368788950 AKERS PHARMACY INC 1595 E GARRISON BLVD GASTONIA NC 28054 7048653411 ALBEMARLE COMPNDN N PRESCRIPT CNT 944 N FIRST ST ALBEMARLE NC 28001 7049836176 ALBEMARLE PHARMACY 105 YADKIN ST ALBEMARLE NC 28001 7049838222 ALLCARE PHARMACY SERVICES, LLC 5176 NC HIGHWAY 42 W STE H GARNER NC 27529 9199267371 ALLEN DRUG 220 S MAIN ST STANLEY NC 28164 7042634876 ALLEN DRUGS INC 9026 HIGHWAY 17 POLLOCKSVILLE NC 28573 2522245591 ALMANDS DRUG STORE 3621 SUNSET AVE ROCKY MOUNT NC 27804 2524433138 ANDERSON CREEK PHARMACY, INC 6779 OVERHILLS RD SPRING LAKE NC 28390 9104976337 ANGIER DISCOUNT DRUG 253 N RALIEGH STREET ANGIER NC 27501 9196399623 ANSON PHARMACY INC 806 CAMDEN RD WADESBORO NC 28170 7046949358 APEX PHARMACY 904 W WILLIAMS ST APEX NC 27502 9196297146 ARCHDALE DRUG AT CORNERSTONE -

Joint Proxy Statement of CVS Corporation and Caremark Rx, Inc

MERGER PROPOSED YOUR VOTE IS VERY IMPORTANT The boards of directors of CVS Corporation and Caremark Rx, Inc. have each approved a merger agreement which provides for the combination of the two companies in a transaction structured as a merger of equals. The boards of directors of CVS and Caremark believe that the combination of the two companies will be able to create substantially more long-term stockholder value than either company could individually achieve. Following the completion of the merger, Caremark will be a wholly owned subsidiary of CVS and Caremark stockholders will own approximately 45.5% of the outstanding common stock of the combined company and CVS stockholders will own approximately 54.5% of the outstanding common stock of the combined company, in each case, on a fully diluted basis. CVS Corporation is referred to as CVS and Caremark Rx, Inc. is referred to as Caremark. The combined company will be named CVS/Caremark Corporation and the shares of the combined company will be traded on the New York Stock Exchange, or the NYSE, under the symbol CVS . If the merger is completed, Caremark s stockholders will receive 1.670 shares of common stock of CVS/Caremark, for each share of Caremark common stock that they own immediately before the effective time of the merger. Caremark stockholders will receive cash for any fractional shares which they would otherwise receive in the merger. Caremark stockholders will also receive a one-time special cash dividend in the amount of $2.00 per share of Caremark common stock held by each such holder on a record date to be set by the Caremark board of directors, which dividend will be conditioned on the completion of the merger and will be paid at or immediately following the effective time of the merger. -

Statesman.Org News3

the stony brook *Ramadan, pg. 2 * Something complet Stts"a ! 11"Casiid History of Stony ,Brook pg. 3 I VOLUME XLIX, ISSUE 11 MONDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2005. PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY Tuition Hike Draws tron minSuor J BY JOSEPH WEN due to her presence at another meeting Senator LaValle responded to Mc- summer programs and specialized flight Staff Writer concerning the Brookhaven National Lab- Grath's testimony by stating that "an and security service training programs, oratory, and was represented by Provost increase in tuition is not that beneficial combine to merit more funding. Asserting Last Thursday, State Senator Kenneth Robert McGrath. McGrath asserted that to University Centers...increase in tu- that "we never recovered from... [2004's] P. LaValle, the chairman of the Senate certain aspects of Stony Brook's present ition benefits the four-year colleges." He extreme cut in state support," President Higher Education Committee, held the situation necessitate more funds, such as remarked that "on differential tuition, it Gibraltar unambiguously stated that "we first of four hearings "to investigate the the need to efficiently operate the new has been the policy of this committee simply cannot continue to educate our future of higher education in the public Humanities building and the desire to not to support that." He then pointed students with our budget." Overall, he sector" in conjunction with various other bring the University "up to par" with the out that "what is beneficial is state sup- painted a bleak picture of his campus' state senators and assembly members,. other universities participating in AAU port." According to Senator LaValle, the situation, expounding upon buildings in and Ron Canestrari, the chairman of the (Association of American Universities). -

Health Options Program

Pennsylvania Public School Participating Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS) Pharmacy Directory Health FOR THE BASIC AND ENHANCED MEDICARE Rx OPTIONS This booklet provides a list of the Options HOP Basic and Enhanced Medicare Rx Plan participating network Program pharmacies. This directory is current as of January 1, 2009. Pharmacies may have been added or removed GEORGIA 2009 from the list after this directory was printed. Therefore, all network pharmacies may not be listed in this directory and the fact that the pharmacy is listed in the directory does not guarantee that the pharmacy is still in the network. To get current information about participating network pharmacies in your area, please visit the HOP Web site at www.HOPbenefits.com or contact Prescription Solutions Customer Service at (888) 239-1301, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. (TTY/TDD users should call (800) 498-5428.) Introduction pharmacy or through our mail-order pharmacy This booklet provides a list of participating HOP service. Once you go to a particular pharmacy, Basic and Enhanced Medicare Rx Plan network you are not required to continue going to the pharmacies and includes some basic information same pharmacy to fill future prescriptions; you about how to best utilize the pharmacy network can go to any of our network pharmacies. to have your prescriptions filled. A complete We will reimburse beneficiaries for covered description of your prescription drug coverage, prescriptions filled at non-network pharmacies including how to have your prescriptions under certain circumstances as described later. filled, is included in the 2009 Annual Notice of Change and Evidence of Coverage document. -

Committee Counsel Employment Application

Case 20-33900 Document 533 Filed in TXSB on 09/04/20 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION ---------------------------------------------------------------x : In re : Chapter 11 : TAILORED BRANDS, INC., et al.,1 : Case No. 20-33900 (MI) : : Jointly Administered Debtors. : ---------------------------------------------------------------x APPLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL COMMITTEE OF UNSECURED CREDITORS PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 327, 330, AND 1103 OF THE BANKRUPTCY CODE, FEDERAL RULES OF BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURE 2014(a) AND 2016, AND LOCAL RULES 2014-1 AND 2016-1 FOR AUTHORIZATION TO RETAIN AND EMPLOY PACHULSKI STANG ZIEHL & JONES LLP AS LEAD COUNSEL EFFECTIVE AS OF AUGUST 12, 2020 THIS APPLICATION SEEKS AN ORDER THAT MAY ADVERSELY AFFECT YOU. IF YOU OPPOSE THE APPLICATION, YOU SHOULD IMMEDIATELY CONTACT THE MOVING PARTY TO RESOLVE THE DISPUTE. IF YOU AND THE MOVING PARTY CANNOT AGREE, YOU MUST FILE A RESPONSE AND SEND A COPY TO THE MOVING PARTY. YOU MUST FILE AND SERVE YOUR RESPONSE WITHIN 21 DAYS OF THE DATE THIS WAS SERVED ON YOU. YOUR RESPONSE MUST STATE WHY THE APPLICATION SHOULD NOT BE GRANTED. IF YOU DO NOT FILE A TIMELY RESPONSE, THE RELIEF MAY BE GRANTED WITHOUT FURTHER NOTICE TO YOU. IF YOU OPPOSE THE APPLICATION AND HAVE NOT REACHED AN AGREEMENT, YOU MUST ATTEND THE HEARING. UNLESS THE PARTIES AGREE OTHERWISE, THE COURT MAY CONSIDER EVIDENCE AT THE HEARING AND MAY DECIDE THE MOTION AT THE HEARING. REPRESENTED PARTIES SHOULD ACT THROUGH THEIR ATTORNEY. The Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors (the “Committee”) of Tailored Brands, Inc. and its affiliated debtors (collectively, the “Debtors”) hereby submits its application (the “Application”) for the entry of an order, pursuant to sections 328(a) and 1103(a) of Title 11 of 1 A complete list of each of the Debtors in these chapter 11 cases may be obtained on the website of the Debtors’ claims and noticing agent at http://cases.primeclerk.com/TailoredBrands. -

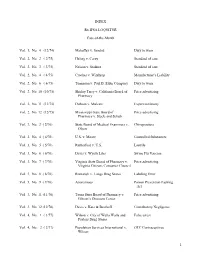

INDEX Rx IPSA LOQUITUR Case-Of-The-Month Vol. 1, No. 4

INDEX Rx IPSA LOQUITUR Case-of-the-Month Vol. 1, No. 4 (12/74) Mahaffey v. Sandoz Duty to warn Vol. 2, No. 2 ( 2/75) Heling v. Carey Standard of care Vol. 2, No. 3 ( 3/75) Nelson v. Stadner Standard of care Vol. 2, No. 4 ( 4/75) Crocker v. Winthrop Manufacturer’s Liability Vol. 2, No. 6 ( 6/75) Tonneson v. Paul B. Elder Company Duty to warn Vol. 2, No. 10 (10/75) Shirley Terry v. California Board of Price advertising Pharmacy Vol. 2, No. 11 (11/75) Dobson v. Mulcare Expert testimony Vol. 2, No. 12 (12/75) Mississippi State Board of Price advertising Pharmacy v. Steele and Schub Vol. 3, No. 2 ( 2/76) State Board of Medical Examiners v. Chiropractors Olson Vol. 3, No. 4 ( 4/76) U.S. v. Moore Controlled Substances Vol. 3, No. 5 ( 5/76) Rutherford v. U.S. Laetrile Vol. 3, No. 6 ( 6/76) Davis v. Wyeth Labs Swine Flu Vaccine Vol. 3, No. 7 ( 7/76) Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Price advertising Virginia Citizens Consumer Council Vol. 3, No. 8 ( 8/76) Romanyk v. Longs Drug Stores Labeling Error Vol. 3, No. 9 ( 9/76) Anonymous Poison Prevention Packing Act Vol. 3, No. 11 (11/76) Texas State Board of Pharmacy v. Price advertising Gibson’s Discount Center Vol. 3, No. 12 (12/76) Davis v. Katz & Besthoff Contributory Negligence Vol. 4, No. 1 ( 1/77) Wilson v. City of Walla Walla and False arrest Payless Drug Stores Vol. 4, No. 2 ( 2/77) Population Services International v. -

CVS Digital Capabilities

Digital Capabilities Connecting members, patients and customers to our services anytime, anywhere. Table of Contents Our Digital Strategy ............... 4 Helping people save CVS Caremark® ...................... 6 time, save money CVS Specialty® ....................... 8 Omnicare® and and stay healthy. Medicare Part D ................... 10 CVS Pharmacy® and Here at CVS Health, we’re reinventing pharmacy to help people on their CVS MinuteClinic™ ............... 12 path to better health. Our commitment to digital innovation is one way we’re putting our purpose into action. Front Store ............................ 14 Throughout all of our service brands, we offer members, patients and customers a suite of digital tools that make managing their health more accessible, more intuitive and more integrated across all our channels. Moving forward, we’ll continue to transform the future of health care by redefi ning convenience and improving the health outcomes of millions of people. 2 3 Build Develop the ultra-convenient, fully integrated pharmacy Our experience only CVS Health can provide across our service brands (CVS Pharmacy, Digital CVS MinuteClinic, CVS Caremark, Strategy CVS Specialty and Omnicare). Digital tools are Personalize transforming the way Provide individualized customer consumers shop and interactions, leveraging data across manage their health care. all touch points to help members, patients and customers on their We’re responding to path to better health. these changing needs by differentiating the customer experience through three Innovate strategic pillars. Harness critical digital trends through rapid testing/learning/ iteration and third-party collaboration at the CVS Health Digital Innovation Lab. 4 5 Member Set Up Print Rx History Easy Refill Makes budgeting and tax prep Offers members a simple way Early Registration easier by allowing members to to refill by scanning the barcode Allows members to register and print a list of prescription costs. -

Robert J. Desalvo Papers Business Combinations in the Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries 1944

Robert J. DeSalvo Papers Business Combinations in the Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries 1944 - 1990 Collection #107 Abstract Robert J. DeSalvo’s research focused on business combinations (acquisitions, mergers, and joint ventures in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. This topic was the basis for his master’s thesis in pharmacy administration at the University of Pittsburgh and continued as a life-long interest. This collection consists of two series of notebooks that Dr. DeSalvo developed to record relevant business combinations. The first series records acquisitions, proposed acquisitions, mergers, and joint ventures for the period of 1944 –1990 in an alphabetical arrangement. The information on these entries is cumulative so that the history of an organization is collected in one place. The second series of notebooks is arranged in chronological blocks. The information is arranged alphabetically by the name of the acquirer. The name of the acquired (merged), type of combination (acquisition, proposed acquisition, joint venture) and the date is also provided. The information is cross-referenced between the two series so that the researcher can approach the information by the name of the parent company or chronologically. Dr. DeSalvo used this resource for many of his publications as well as his master’s thesis. A copy of these publications and his thesis make up the remainder of the collection. Donor Gift of Barbara DeSalvo, 2000 Biography Robert James DeSalvo was born on July 20, 1933 in Toledo, OH. He died on January 23, 1993 in Cincinnati, OH. DeSalvo graduated from high school in Toledo and attended pharmacy school at the University of Toledo where he received his B.S. -

Your Benefits Card Merchant List

Your Benefits Card Merchant List ¾ Use your benefits card at these stores that can identify FSA/HRA eligible expenses. ¾ Check the list to find your store before you order prescriptions or shop for over-the- counter (OTC) items. ¾ Swipe your benefits card first and only your FSA/HRA eligible purchases will be deducted from your account. ¾ You won’t have to submit receipts to verify purchases from these stores, but you should still save your receipts for easy reference. ¾ Merchants have the option of accepting MasterCard and/or Visa for payment. Before making a purchase with your benefits card, please make sure you know which cards are accepted. Ist America Prescription Drugs* Albertville Discount Pharmacy* AmiCare Pharmacy Inc* 3C Healthcare Inc, dba Medicap Alden Pharmacy* Anderson and Haile Drug Store* Pharmacy* Alert Pharmacy Services-Mt Anderson County Discount 50 Plus Pharmacy* Holly* Pharmacy* A & P* Alexandria Drugs Inc* Anderson Drug-Athens TX* Aasen Drug* Alfor’s Pharmacy* Anderson Pharmacy-Denver PA Abeldt’s Gaslight Pharmacy* Allcare Pharmacy* Anderson Pharmacy/John M* ACME * Allen Drug* Anderson’s Pharmacy* Acres Market (UT) * Allen’s Discount Pharmacy* Andrews Pharmacy* Acton Pharmacy Allen Family Drug* Anthony Brown Pharmacy Inc* Adams Pharmacy* Allen’s Foodmart* Antwerp Pharmacy* Adams Pharmacy Inc* Allen’s of Hastings, Inc.* Apotek Inc. Adams Pharmacy and Home Allen's Super Save #1 Provo Apotek Pharmacy* Care* UT* Apoteka Compounding LLC* Adamsville Pharmacy* Allen's Super Save #2 Orem UT* Apothecare Pharmacy* Adrien Pharmacy* -

Three Village Hamlet Stuoly 1997 a Citizens' Blueprint for Our Future

Three Village Hamlet Stuoly 1997 A Citizens' Blueprint for Our Future • }- . ~. I I Three Village Hamlet Study 1997 A Citizens' Blueprint for our Future ) On Long Island's North Shore, midway between the Brooklyn Bridge and Montauk Point, hidden from the main roads and parkways, lie the villages ,!f Setauket, Stony Brook, and Old Field. Nestled snugly beside their beautiful bays and harbors, the villages present to the visitor a vision of a modern, thriving, well~cared~f(}r ('ommunity. But there is more. At every turn an aura of history pervades the land. The ghosts '!f a mighty past stalk the broad fields and the quiet, tree-bordered streets and lanes. Old England and New England are there, in the family names, in the viliage greens, in the architecture of the houses, in the manners and customs of the people. Colonial America and mOl/ern America are there. Perhaps it is this blending of the old and the new that lends these Brookhaven villages their air of enchantment. Setauket, the oldest of the three, is the site of the first settlement in Brookhaven Town . ... Edwin P. Adkins, Setauket, 1655 - 1955: The First Three Hundred Years (New York, 1955) p.l The Three Village Hamlet Study Task Force Acknowledgements This Study is the product of prolonged effort by a dedicated band of citizens. the members of the Three Village Hamlet Study Task Force: Cynthia Barnes· Chair. Land Use Committee Lou Bluestein Malcolm Bowman Jean and Robert Caire· Jim Coughlan· Alice D'Amico Robert deZafra· Katherine Downs· Lou ise Harrison o 1effHom* Berhane Ghebrehiwet Homer Goldberg Camille 10hnson Richard Kew Mike Kaufman JP Leiz Barbara Levy ) David Madigan Stephen Mathews Louis Medina Stephen and Luci Nash Brian Newman· Chair.