The Slits, Lora Logic, and the Raincoats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibitionein Film Von Joanna Hogg Mit Viv Albertine, Liam Gillick & Tom Hiddleston

EXHIBITION ein Film von Joanna Hogg mit Viv Albertine, Liam Gillick & Tom Hiddleston | UK 2013 | 104 Minuten | englische Originalfassung mit deutschen Untertiteln | Fugu Filmverleih | Deutscher Kinostart: 11. Dezember 2014 “It’s in the Walls!” D in EXHIBITION SYNOPSIS Zwei Künstler, ein Haus, eine unkonventionelle Ehe. H und D leben in einem extravaganten Bau im Londoner Stadtteil Kensington. Sie arbeiten parallel an ihren Projekten, geben Telefoninterviews, lassen die Außenwelt nur gedämpft herein und verabreden sich über die Haussprechanlage zu Sex oder Abendessen. H. hat das Gefühl, schon zu lange an einem Ort zu leben. Er überzeugt D, das Haus zu verkaufen. Im Prozess der Ablösung gerät die Beziehung in eine Krise. Plötzlich erhält D, die Angst vor Veränderungen hat, das Angebot einer großen Einzelausstellung. Wird die Ehe zerbrechen oder ein Neuanfang gelingen? Stellt sich heraus, dass ihr Traumhaus die ganze Zeit schon ein Gefängnis war? PRESSENOTIZ EXHIBITION, der dritte Film der „einzigartig begabten Filmemacherin“ (Martin Scorsese) Joanna Hogg, ist ein großstädtisches Kammerspiel mit drei Darstellern: der Ex-Slits-Gitarristin Viv Albertine, dem Maler und Objektkünstler Liam Gillick und dem „H-House“ des Architekten James Melvin. PRODUKTIONSNOTIZEN EXHIBITION ist der dritte Spielfilm von Joanna Hogg, einer vor allem von der britischen Filmkritik umjubelten Filmregisseurin und –autorin, die 2007 mit UNRELATED auf sich aufmerksam machte und deren zweiter Spielfilm ARCHIPELAGO (2010) auch in Deutschland ins Kino kam. Beide Filme zeigten Hoggs Talent für Ensemblechoreografien, für einen analytisch- beobachtenden Stil und einen scharfen Blick auf die englische Mittelklasse – deren Verhaltensweisen, Ängste, Tabus und Verletzlichkeiten sie sehr genau kennt. UNRELATED und ARCHIPELAGO sind raue emotionale Dramen und spröde Sozialkomödien gleichermaßen, die ihre Autorin als originelle neue Stimme im britischen Kino ausweisen. -

The Forgotten Revolution of Female Punk Musicians in the 1970S

Peace Review 16:4, December (2004), 439-444 The Forgotten Revolution of Female Punk Musicians in the 1970s Helen Reddington Perhaps it was naive of us to expect a revolution from our subculture, but it's rare for a young person to possess knowledge before the fact. The thing about youth subcultures is that regardless how many of their elders claim that the young person's subculture is "just like the hippies" or "just like the mods," to the committed subculturee nothing before could possibly have had the same inten- sity, importance, or all-absorbing life commitment as the subculture they belong to. Punk in the late 1970s captured the essence of unemployed, bored youth; the older generation had no comprehension of our lack of job prospects and lack of hope. We were a restless generation, and the young women among us had been led to believe that a wonderful Land of Equality lay before us (the 1975 Equal Opportunities Act had raised our expectations), only to find that if we did enter the workplace, it was often to a deep-seated resentment that we were taking men's jobs and depriving them of their birthright as the family breadwinner. Few young people were unaware of the angry sound of the Sex Pistols at this time—by 1977, a rash of punk bands was spreading across the U.K., whose aspirations covered every shade of the spectrum, from commercial success to political activism. The sheer volume of bands caused a skills shortage, which led to the cooption of young women as instrumentalists into punk rock bands, even in the absence of playing experience. -

OZ 17 Richard Neville Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online OZ magazine, London Historical & Cultural Collections 12-1968 OZ 17 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1968), OZ 17, OZ Publications Ink Limited, London, 48p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon/17 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] OZ 17 Description Editor: Richard Neville. Design: Jon Goodchild. Writers: Andrew Fisher, Ray Durgnat, David Widgery, Angelo Quattrocchi, Ian Stocks. Artists: Martin Sharp, John Hurford, Phillipe von Mora. Photography: Keith Morris Advertising: Felix Dennis, REN 1330. Typesetting: Jacky Ephgrave, courtesy Thom Keyes. Pushers: Louise Ferrier, Felix Dennis, Anou. This issue produced by Andrew Fisher. Content: Louise Ferrier colour back issue/subscription page. Anti-war montage. ‘Counter-Authority’ by Peter Buckman. ‘The alH f Remarkable Question’ - Incredible String Band lyric and 2p illustration by Johnny Hurford. Martin Sharp graphics. Flypower. Poverty Cooking by Felix and Anson. ‘The eY ar of the Frog’ by Jule Sachon. ‘Guru to the World’ - John Wilcock in India. ‘We do everything for them…’ - Rupert Anderson on homelessness. Dr Hipocrates (including ‘inflation’ letter featured in Playpower). Homosexuality & the law. David Ramsay Steele on the abolition of Money. ‘Over and Under’ by David Widgery – meditations on cultural politics and Jeff uttN all’s Bomb Culture. A Black bill of rights – LONG LIVE THE EAGLES! ‘Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Mall’ - the ethos of the ICA. Graphic from Nottingham University. Greek Gaols. Ads for Time Out and John & Yoko’s Two Virgins. -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

A Film by Joanna Hogg

presents EXHIBITION A FILM BY JOANNA HOGG UK / COLOUR / 104 MINUTES / 2013 A Kino Lorber Release from Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 West 39 St., Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contacts: Rodrigo Brandão – [email protected] Matt Barry – [email protected] SHORT SYNOPSIS When D and H decide to sell the home they have loved and lived in for two decades, they begin a process of saying goodbye to their shared history under the same roof. The upheaval causes anxieties to surface, and wife and performance artist D, struggles to control the personal and creative aspects of her life with H. Dreams, memories, fears, have all imprinted themselves on their home, which exists as a container for their lives and has played such an important role in their relationship. LONG SYNOPSIS Artists D (Viv Albertine) and H (Liam Gillick) are a married couple who have lived together in a West London house for nearly 20 years. It is a modernist house - all verticals, reflecting windows and sliding partitions – and seemingly the ideal residence for two artists who each work independently at home in their separate spaces, occasionally communicating briefly by intercom. Throughout EXHIBITION we see D and H living together, working separately, communicating or failing to communicate – in a series of moments depicting a long-term relationship that sometimes seems to be in meltdown, at other times extremely strong. It’s autumn. H suggests to D that she’s unwilling to discuss her work with him; she says she’s reluctant to expose herself to his criticism. -

Life Itself’: a Socio-Historic Examination of FINRRAGE

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by White Rose E-theses Online From ‘Death of the Female’ to ‘Life Itself’: A Socio-Historic Examination of FINRRAGE Stevienna Marie de Saille Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2012 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2012, The University of Leeds and Stevienna Marie de Saille The right of Stevienna Marie de Saille to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number of people who made this thesis possible in a number of different, fantastically important ways. My deepest thanks to: - My supervisors, Prof. Anne Kerr and Dr. Paul Bagguley, for their patience, advice, editorial comments, and the occasional kickstart when the project seemed just a little(!) overwhelming, and my examiners, Prof. Maureen McNeil and Dr. Angharad Beckett for their insight and suggestions. - The School of Sociology and Social Policy, for awarding me the teaching bursary which made this possible, and all the wonderful faculty and support staff who made it an excellent experience. - The archivists in Special Collections at the University of Leeds, and to the volunteers at the Feminist Archive North for giving me an all-access pass. -

DISCO! an Interdisciplinary Conference

DISCO! An Interdisciplinary Conference 21-23 June 2018 Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts University of Sussex WELCOME TO DISCO! This programme provides a full schedule for the conference. For further information about the presentations and the contributors, please refer to the abstracts section on the conference website: https://discosussex2018.wordpress.com If you would like to use wifi, the venue password is: upliftingly scoff their raven If you would like to tweet our conference, please do! @disco_conf We would love to hear from you about your experience at Disco! There is a comments book at the registration desk and a feedback section on the conference website. Recommendations of local eats and drinks in Brighton can also be found on the website. If you have an emergency and need to speak to a conference organiser, please call Arabella (07747 797 254), Michael (07973 317876) or Mimi (07492 771318) or email [email protected] The conference organisers would like to thank the Drama Public Programme, the School of English, the School of Media, Film and Music, everyone at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts, and especially, Greg Mickelborough, Laura McDermott, Matt Knight, Nicola Jeffs, Melissa Cox, and Jodie Grey, and our colleagues Patrick Reed, Sarah Maddox, Danielle Salvage, Lizzie Thynne, Jason Price, Carol Watts, Wayne Spicer, and Alison O’Gorman. A special thanks to our student stewards: Zoë Bothwell, Tom Chown, Neve Mclennon, and Jemima Harney. Catering: spacewithus A big thank you to everyone who is sharing their work at Disco! Enjoy the conference! The DISCO! Team Mimi Haddon Michael Lawrence Arabella Stanger Thursday 21 June 1.30 – 2.00 Gardner Tower Registration and Refreshments 2.00 – 2.15 ACCA Auditorium Welcome! 2.15 – 3.30 ACCA Auditorium Keynote Presentation Melissa Blanco Borelli (Royal Holloway, University of London) "Put Your Body In It": Disco, Divas, and Dance Studies Stephanie Mills’ disco classic, “Put Your Body In It” invites us to get up, free ourselves and just dance. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

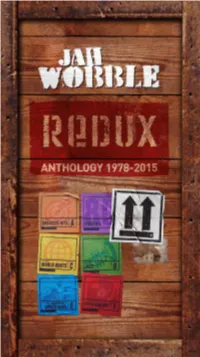

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

How to Organise a Reclaim the Night March

How to organise a Reclaim the Night march First of all, it’s good to point out what Reclaim the Night (RTN) is. It’s traditionally a women’s march to reclaim the streets after dark, a show of resistance and strength against sexual harassment and assault. It is to make the point that women do not have the right to use public space alone, or with female friends, especially at night, without being seen as ‘fair game’ for harassment and the threat or reality of sexual violence. We should not need chaperones (though that whole Mr Darcy scene is arguably a bit cool, as is Victorian clothing, but not the values). We should not need to have a man with us at all times to protect us from other men. This is also the reason why the marches are traditionally women-only; having men there dilutes our visi- ble point. Our message has much more symbolism if we are women together. How many marches do you see through your town centre that are made up of just women? Exactly. So do think before ruling out your biggest unique selling point. Anyway, the RTN marches first started in several cities in Britain in November 1977, when the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) was last at its height, a period called the Second Wave. The idea for the marches was copied from co-ordinated midnight marches across West German cities earlier that same year in April 1977. The marches came to stand for women’s protest against all forms of male violence against women, but particularly sexual vio- lence. -

A Quienes Los Dioses Enloquecen

A quienes los dioses enloquecen Rafael Toriz Por vivir en tiempos donde la intimidad de cualquier hijo de vecino obedece —aunque sobre todo simula— a la lógica del espectáculo, olvidamos que el género de la biografía —tan envilecido en el presente por la autoficción, los libros en primera per- sona y la sobre exposición del yo en diversas plataformas— solía tener una impronta única porque contaba la historia de personajes que por alguna razón particular mere- cían ser destacados del olvido de la historia o al menos de la banalidad constitutiva de la mayor parte de la especie. Hoy por hoy Instagram es el realismo social de nuestro tiempo, imágenes donde una mayoría enajenada cree encarnar la imagen de la felici- dad y sobre todo cree en la necesidad de compartirlo. Si bien toda vida encierra misterios y ensenñanzas (no todos dignos de ser con- tados), hay existencias que han dado forma y contenido inigualable a la cultura popu- lar, de ahí su merecida o inflada celebridad. Por ello, resulta neurálgico señalar que el libro de memorias Ropa música chicos, de Viv Albertine, es un testimonio desde las en- trañas —contado por una mujer, cosa que siempre se agradece— del nacimiento de una de las sensibilidades más auténticas y potentes del siglo xx: el punk rock en Inglaterra. Contada en primera persona por un testigo protagonista de un momento irrepe- tible, la efervescencia que describe la ubica no como una groupie, sino como una de las pocas personas que sobrevivió a una época de descubrimientos y tumultos que dio lugar a una música nueva y a una sensibilidad que, aun pese al estado del necrocapita- lismo en el que vivimos, impacta y permance en el presente por auténtica y desgarrada, por decirlo con Henry Rollins.