The Southeastern Alaska Tourism Industry: Historical Overview and Current Status

Total Page:16

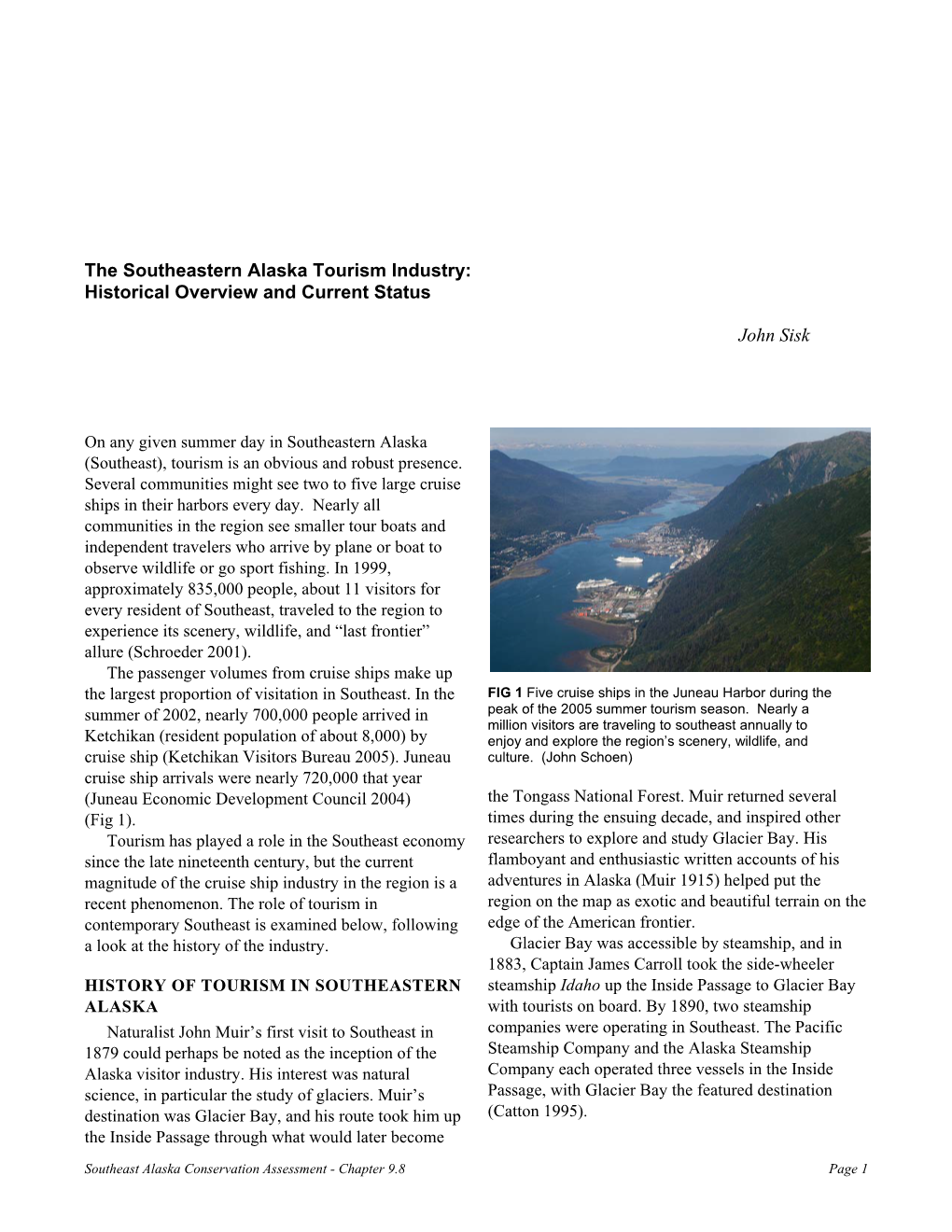

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska's Glaciers S Glaciers Inside Passage

AALASKALASKA’S GGLACIERSLACIERS AANDND TTHH E IINSIDENSIDE PPASSAGEASSAGE J UUNEAUN E A U ♦ S IITKAT K A ♦ K EETCHIKANT C H I K A N ♦ T RRACYA C Y A RRMM A LLASKAA S KA ' S M AAGNIFICENTG N I F I C E N T C OOASTALA S TA L G LLACIERSA C I E R S M IISTYS T Y F JJORDSO R D S ♦ P EETERSBURGT E R S B U R G ♦ V AANCOUVERN C O U V E R A voyage aboard the Exclusively Chartered Small Ship Five-Star M.S. LL’A’AUUSTRALSTRAL July 18 to 25, 2015 ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dear Villanova Traveler, Arctic-blue glaciers, rarely observed marine life, pristine waters, towering mountains, untouched coastlines and abundant wildlife. These are the wondrous sights that will unfold around you on this comprehensive and exceptional Five-Star small ship cruise of Alaska’s glaciers and the Inside Passage, last of the great American frontiers. Enjoy this one-of-a-kind pairing of Five-Star accommodations with exploration-style travel as you cruise the Inside Passage from Juneau, Alaska, to Vancouver, British Columbia, during the divine long days of summer. Exclusively chartered for this voyage, the Five-Star small ship M.S. L’AUSTRAL, specially designed to navigate the isolated inlets and coves of the Inside Passage inaccessible to larger vessels, brings you up close to the most spectacular scenery of southeastern Alaska and Canada, offering you a superior wildlife-viewing experience—from sheltered observation decks, during Zodiac expeditions led by seasoned naturalists and from the comfort of 100% ocean-view Suites and Staterooms, most with a private balcony. -

The Heart of Ontario Regional Tourism Strategy

Hamilton Halton Brant Regional Tourism Association (RTO 3) Regional Tourism Strategy Update 2015-2018 November 2014 1 Millier Dickinson Blais: RTO 3 Regional Tourism Strategy Review Final Report Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 4 2 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 HHBRTA ORGANIZATION 7 2.1.1 DESTINATION VISITOR EXPERIENCE BRANDING 8 2.1.2 PREVIOUS WORK 9 3 SECTOR ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................ 20 3.1 TOURISM – A GLOBAL DRIVER 20 3.1.1 GLOBAL TOURISM TRENDS TO WATCH 21 3.2 THE CANADIAN TOURISM CONTEXT 23 3.2.1 CANADIAN TOURISM MARKETS 24 3.2.2 ABORIGINAL TOURISM IN CANADA 25 3.3 TOURISM IN THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO 26 3.3.1 PROVINCIAL VISITOR TRENDS 27 3.3.2 ONTARIO TOURISM CHALLENGES 28 3.3.3 ARTS AND CULTURE 28 3.4 RTO 3 REGION VISITOR TRENDS 29 3.4.1 TOURISM METRICS BY CENSUS DIVISION 33 3.4.2 NEIGHBOURING RTO COMPARATIVE STATISTICS 36 3.4.3 VISITOR FAMILIARITY AND INTEREST IN ONTARIO’S RTO’S 39 3.5 ACCOMMODATIONS SECTOR REVIEW 41 4 CONSULTATIONS ................................................................................................................ 47 4.1 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATIONS 47 4.1.1 BRANT 47 4.1.2 HALTON 48 4.1.3 HAMILTON 49 4.1.4 SIX NATIONS 50 4.1.5 ACCOMMODATION SECTOR ONLINE SURVEY 51 4.1.6 DESTINATIONS MARKETING ORGANIZATIONS -

The Use of Souvenir Purchase As an Important Medium for Sustainable Development in Rural Tourism: the Case Study in Dahu, Mioli County, Taiwan

2009 National Extension Tourism (NET) Conference The use of souvenir purchase as an important medium for sustainable development in rural tourism: The case study in Dahu, Mioli county, Taiwan Tzuhui A. Tseng, Ph. D. Assistant Professor, Department of Regional Studies in Humanity and Social Sciences, National Hsinchu University of Education, Taiwan David Y. Chang, Ph. D. Associate Professor, School of Hotel & Restaurant Management, University of South Florida Ching-Cheng Shen, Ph. D. Associate Professor, The Graduate School of Travel Management, National Kaohsiung Hospitality College Outline • Introduction • Literature review • RhdiResearch design • Result • Conclusion and suggestion Graburn (1977) stated that very few visitors would not bring back anything to showoff their trip after coming back from a vacation. Int r oduction Introduction • Souvenir becomes destination or attraction – Tourists not only come visit for its special local scenery or cultural activity, but sometimes for its spppecial local product as well. – It is a very common custom for Taiwanese tourists to purchase local souvenirs as gifts to bring back to friends and family. • Souvenir bring big economy – Turner and Reisinger (2000) indicated that tourists spent 2/3 of their total cost on shopp in g when t ra ve ling dom esti call y, an d 1/5 o f t he tota l cost w en t in to sh oppin g when traveling internationally. – Shopping is a main or secondary factor for traveling, and is very important to tourists. it often is an important factor for whether a trip is successful. • Niche tourism or Special interest tourism – There are not many related studies on souvenir purchasing in recent years. -

Lewiston, Idaho

and brother, respectively, of Mrs. ■ w Crtp Sears. Mr. Sears and Mr. K night were To Cure a Cold in One Day T w o Day«. discharged from the hospital several days ago, as they both gave up only Lewiston Furniture and Under T)& Laxative Brom o Quinine t m a . on «vary about one half as much skin as did MBBon k a m u M h ^ a t 13 5«v«n Tins i Mr. Isivejov, and the recovery was in (S.Cfcdfr box. 25c. consequence much more rapid. The Operation, which was perform taking Company ed by Dr. C. P. Thomas was more suc oooooooooooooooooo "on and only heir. Property is an oooooc.ooooooooooo cessful than the surgeon expected. SO acre farm in Nez Perce county, Every portion of the skin grafted onto 0 h e r e a n d THERE O o o J. C. Harding Dessie E. Harding some lots in Lewiston, and a lot of O PERSONAL MENTION O the woman's body adhered and has 0 0 mining shares—say about 135,000—in grown fast, and in consequence she is JOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO O O the Gold Syndicate and the Jerrico oooooooooooooooooo greatly improved and suffers compara The Tuesday evening Card club will mines. tively little pain. The skin was burned Funeral D irectors and ine,.. with Mrs. F. D. Culver tonight. I. J. Taylor, of Orofino, is in the city. off her body from the small of the U H Kennedy, many years chief W. Wellman, of Orofino, is in the back to the feet, through a fire in her jL g. -

Sitka Area Fishing Guide

THE SITKA AREA ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ROADSIDE FISHING .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 ROADSIDE FISHING IN FRESH WATERS .................................................................................................................................... 4 Blue Lake ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Beaver Lake ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sawmill Creek .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Thimbleberry and Heart Lakes .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Indian River ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Swan Lake ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Sea Kayaking on the Petersburg

SeaSea KayakingKayaking onon thethe PetersburgPetersburg RangerRanger DistrictDistrict Routes Included in Handout Petersburg to Kake via north shore of Kupreanof Island Petersburg to Kake via south shore of Kupreanof Island LeConte Bay Loop Thomas Bay Loop Northwest Kuiu Island Loop Duncan Canal Loop Leave No Trace (LNT) information Tongass National Forest Petersburg Ranger District P.O. Box 1328 Petersburg AK. 99833 Sea Kayaking in the Petersburg Area The Petersburg area offers outstanding paddling opportunities. From an iceberg filled fjord in LeConte Bay to the Keku Islands this remote area has hundreds of miles of shoreline to explore. But Alaska is not a forgiving place, being remote, having cold water, large tides and rug- ged terrain means help is not just around the corner. One needs to be experienced in both paddling and wilderness camping. There are not established campsites and we are trying to keep them from forming. To help ensure these wild areas retain their naturalness it’s best to camp on the durable surfaces of the beach and not damage the fragile uplands vegetation. This booklet will begin to help you plan an enjoyable and safe pad- dling tour. The first part contains information on what paddlers should expect in this area and some safety guidelines. The second part will help in planning a tour. The principles of Leave No Trace Camping are presented. These are suggestions on how a person can enjoy an area without damaging it and leave it pristine for years to come. Listed are over 30 Leave No Trace campsites and several possible paddling routes in this area. -

Alaska's Glaciers and the Inside Passage

ALASKA’s GlaCIERS AND THE INSIDE PASSAGE E S TABLISHED 1984 Point FIVE-STAR ALL-SUITE SMALL SHIP Inian Islands Adolphus JUNEAU ALASKA Elfin Icy Strait Sawyer FAIRBANKS U.S. 4 Cove Glacier Denali CANADA National ANCHORAGE EXCLUSIVELY CHARTERED Tracy Arm Park JUNEAU Inside Endicott Arm Passage M.V. STAR LEGEND Peril Misty Fjords Dawes Glacier KETCHIKAN Strait Gulf of Alaska Frederick VANCOUVER Sound SITKA C h a WRANGELL t Cruise Itinerary h a The Narrows Air Routing m Train Routing S t r Land Routing a i Inside Passage t KETCHIKAN JULY 5 TO 12, 2018 ◆◆ Only 106 Five-Star Suites ITINERARY* ◆◆ Walk-in closet and large sitting area Juneau, Tracy Arm, Sitka, Wrangell, Ketchikan, Alaska’s Magnificent Glaciers and ◆◆ 100% ocean-view, all-Suite accommodations Inside Passage, Vancouver ◆◆ Small ship cruises into ports inaccessible 1 Depart home city/Arrive Juneau, Alaska, U.S./ to larger vessels Embark M.V. STAR LEGEND ◆◆ Unique, custom-designed itinerary 2 Tracy Arm Fjord/Sawyer Glacier/ Endicott Arm/Dawes Glacier ◆◆ A shore excursion included in each port 3 Point Adolphus/Inian Islands/Elfin Cove ◆◆ Complimentary alcoholic and nonalcoholic 4 Sitka beverages available throughout the cruise 5 Wrangell ◆◆ 6 Ketchikan Once-in-a-lifetime offering! 7 Cruising the Inside Passage ◆◆ Certified “green” clean ship 8 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada/ Disembark ship/Return to home city oin this one-of-a-kind, exploration-style cruise through Jthe Inside Passage from Juneau to Vancouver during the long days of summer aboard the exclusively chartered Five-Star, all-Suite, small ship M.V. STAR LEGEND. Navigate isolated inlets inaccessible to larger vessels for superior views of Alaska’s spectacular scenery. -

Transportation Whitepaper SAWC 2020

Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary 3 Background on Selling Commercial Products on the Salt and Soil Marketplace 4 Challenges with Regional Shipping Options 5 Ferry: Alaska Marine Highway System 5 Air cargo 6 Barge 6 Innovative use of existing transportation networks 7 Recommendations to overcome transportation barriers for a regional food economy 8 Recommendations for farmers and other rural producers 8 Recommendations for local and regional food advocacy organizations 9 SEAK Transportation Case Study: Farragut Farm 10 Conclusion 11 List of Tables 11 Table 1: Measure of Producer Return on Investment 11 Executive Summary Southeast Alaska is a region of around 70,000 people spread out over a geographic area of about 35,000 square miles, which is almost the size of the state of Indiana. The majority of communities are dependent on air and water to transport people, vehicles, and goods, including food and basic supplies. The current Southeast Alaska food system is highly vulnerable because it is dependent on a lengthy supply chain that imports foods from producers and distribution centers in the lower 48 states. Threats to this food supply chain include natural disasters (wildfires, earthquakes, tsunami, drought, flooding), food safety recalls, transport interruptions due to weather or mechanical failures, political upheaval, and/or terrorism. More recently, the Covid-19 pandemic led to shelter-in-place precautionary measures at the national, state, and community levels in March 2020. Continued uncertainty around the long-term health and safety of food workers in the lower 48 may lead to even more supply shortages and interruptions in the future. -

Leaders Discuss Activism, Apathy

The Monthly Newsmagazine of Boise State University Vol. X, No. 4 Boise Idaho March 1985 Legislators work on budgets for education After already rejecting one appro· priation bill for higher education, state legislators, at FOCUS press time, were searching for funds to add to the budgets of higher education and public schools for fiscal 1986. Earlier in the session, the House of Representatives voted 55·29 against a bill that would have allocated S84.8 million for the Jour state·supported schools. an increase of 7 percent over last year. That bill was criticized by some legislators as inadequate to meet the needs of higher ed.ucation. Proponents of the $84.8 mtllion conference amount, on the other and, said the Gov. John Evans, former Sen. Edmund Muskle and former Gov. Cecil Andrus at reception for Muskle during Church . state could not afford to allocate more if the Legislature is going to Leaders discuss activism, apathy stay within the S575 million revenue projection approved earlier in the "A/}(lthy does no/ confonn to such as why some Americans partici· the U.S. vice president from 1973· 74 session. Americans. either hy tradition or her· pate in the political process and oth· and became president after Richard But the defeat of the initial appro· it age ... Aclit'ism seems to fit our ers don't; what the causes of citizen Nixon's resignation in 1974. priations bill for higher education in understanding of Americanism activism and apathy are; and what Ford said while he encourages the House, coupled with the defeat /()(/(�}'. -

Historic Property Old Capitol Inventory Report for 600 Washington Street SE Olympia, Thurston, 98501

Historic Property Old Capitol Inventory Report for 600 Washington Street SE Olympia, Thurston, 98501 LOCATION SECTION Historic Name: Old Capitol Field Site No.: 901 Common Name: (#34-901) OAHP No.: Property Address: 600 Washington Street SE Olympia, Thurston, 98501 Comments: OLYMPIA/OLYWOMEN County Township/Range/EW Section 1/4 Sec 1/4 1/4 Sec Quadrangle Thurston T18R02W 14 SW TUMWATER UTM Reference Zone: 10 Spatial Type: Point Acquisition Code: TopoZone.com Sequence: 0 Easting: 507740 Northing: 5209735 Tax No./Parcel No. Plat/Block/Lot 78502600000 Sylvester's Blk 26 Supplemental Map(s) Acreage City of Olympia Planning Department 1.43 IDENTIFICATION SECTION Field Recorder: Shanna Stevenson Date Recorded: 7/1/1997 Survey Name: OLYMPIA Owner's Name: Owner Address: City/State/Zip: Washington General PO Box 41019 Olympia, WA 98504 Administration Classification: Building Resource Status Comments Within a District? Yes Survey/Inventory National Register Contributing? State Register Local Register National Register Nomination: OLD CAPITOL BUILDING Local District: National Register District/Thematic Nomination Name: OLYMPIA DOWNTOWN HISTORIC DISTRICT DESCRIPTION SECTION Historic Use: Government - Capitol Current Use: Government - Government Office Plan: H-Shape No. of Stories: Structural System: Stone - Uncut Changes to plan: Moderate Changes to interior: Extensive Changes to original cladding: Intact Changes to other: Changes to windows: Slight Other (specify): Cladding Stone Foundation Stone Style Queen Anne - Richardsonian Romanesque Form/Type -

This City of Ours

THIS CITY OF OURS By J. WILLIS SAYRE For the illustrations used in this book the author expresses grateful acknowledgment to Mrs. Vivian M. Carkeek, Charles A. Thorndike and R. M. Kinnear. Copyright, 1936 by J. W. SAYRE rot &?+ *$$&&*? *• I^JJMJWW' 1 - *- \£*- ; * M: . * *>. f* j*^* */ ^ *** - • CHIEF SEATTLE Leader of his people both in peace and war, always a friend to the whites; as an orator, the Daniel Webster of his race. Note this excerpt, seldom surpassed in beauty of thought and diction, from his address to Governor Stevens: Why should I mourn at the untimely fate of my people? Tribe follows tribe, and nation follows nation, like the waves of the sea. It is the order of nature and regret is useless. Your time of decay may be distant — but it will surely come, for even the White Man whose God walked and talked with him as friend with friend cannot be exempt from the common destiny. We may be brothers after all. Let the White Man be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead — I say? There is no death. Only a change of worlds. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1. BELIEVE IT OR NOT! 1 2. THE ROMANCE OF THE WATERFRONT . 5 3. HOW OUR RAILROADS GREW 11 4. FROM HORSE CARS TO MOTOR BUSES . 16 5. HOW SEATTLE USED TO SEE—AND KEEP WARM 21 6. INDOOR ENTERTAINMENTS 26 7. PLAYING FOOTBALL IN PIONEER PLACE . 29 8. STRANGE "IFS" IN SEATTLE'S HISTORY . 34 9. HISTORICAL POINTS IN FIRST AVENUE . 41 10. -

Haines Highway Byway Corridor Partnership Plan

HAINES HIGHWAY CORRIDOR PARTNERSHIP PLAN 1 Prepared For: The Haines Borough, as well as the village of Klukwan, and the many agencies, organizations, businesses, and citizens served by the Haines Highway. This document was prepared for local byway planning purposes and as part of the submission materials required for the National Scenic Byway designation under the National Scenic Byway Program of the Federal Highway Administration. Prepared By: Jensen Yorba Lott, Inc. Juneau, Alaska August 2007 With: Whiteman Consulting, Ltd Boulder, Colorado Cover: Haines, Alaska and the snow peaked Takhinska Mountains that rise over 6,000’ above the community 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................5-9 2. BACKGROUND ON Byways....................................11-14 3. INSTRINSIC QUALITY REVIEW..............................15-27 4. ROAD & TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM...................29-45 5. ToURISM & Byway VISITATION...........................47-57 6. INTERPRETATION......................................................59-67 7. PURPOSE, VISION, GOALS & OBJECTIVES.......69-101 8. APPENDIX..................................................................103-105 3 4 INTRODUCTION 1 Chilkat River Valley “Valley of the Eagles” 5 The Haines Highway runs from the community byway. Obtaining national designation for the of Haines, Alaska to the Canadian-U.S. border American portion of the Haines highway should station at Dalton Cache, Alaska. At the half way be seen as the first step in the development of an point the highway passes the Indian Village of international byway. Despite the lack of a byway Klukwan. The total highway distance within Alaska program in Canada this should not prevent the is approximately 44 miles, however the Haines celebration and marketing of the entire Haines Highway continues another 106 miles through Highway as an international byway.