Nature's Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2019 Turtle Talk

Spring 2019 Upcoming Events: pg. 1 Conservation Education: pg. 2 Post Season Recap: pg. 3 Donor Spotlight: pg. 4 Photo of the Season! Jared, Educator To be considered for Visitor Photo of the Season, please send photos to [email protected] UPCOMING EVENTS Spring Early Childhood Classes Spring Break Mini-Camp Starts March 2019 Monday, April 15 to Friday, April 19 Early Childhood classes continue through Spring 9am to 4pm daily for our families with preschool aged children. Join Spring into the season with Turtle Back us for this seasonally-themed series of programs Zoo’s Mini-Camp! Tour the zoo, meet our that will introduce your children to the world of animal ambassadors, and learn about your animals! Programs are in March, April, and favorite animals with Turtle Back Zoo’s camp May. Check bit.ly/2UWjC9i for current listings. counselors. Mini-Camp is the perfect way for children ages 5-7 and 8-10 to explore the Summer Camp Open House world in your backyard. Stay tuned for the Saturday, March 9; 11am – 2pm announcement of our theme at bit.ly/2BBMbS3. Free Event Admission, Advanced Registration Recommended. Get ready for summertime at Party for the Planet TBZ’s Summer Camp Open House! Try out Saturday, April 20 and Sunday, April 21 some of our camp activities and meet Included with zoo admission. Association of Zoos some of our animal ambassadors with and Aquariums accredited zoos, like Turtle Back Turtle Back Zoo’s Camp Counselors! Zoo, are taking Party for the Planet to a new Visit bit.ly/2BBMbS3 for more information. -

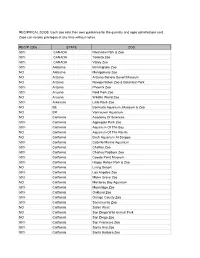

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Henson Robinson

MASTER PLAN Adopted by the Park Board December 15, 2011 Contents Executi ve Summary 1 Springfi eld 2 History of the HRZ 6 Tour of the Zoo 7 Comparisons 15 Process 17 Constructi ng Project Purpose 19 Henson Robinson Zoo Strategic Plan 20 Data Collecti on and Design 27 Data Collecti on and Report Out 28 Data Analysis 32 The Future of HRZ Faciliti es Plan 38 Marketi ng and Branding Plan 49 Educati onal Program Plan 55 Economic Development Plan 59 Budget 64 Implementati on 66 Conclusion Analysis 67 References 68 Professional Services rendered toward the development of the Master Plan Facilitators Architectural Designs and Services Dalitso S. Sulamoyo, Ph.D Bruce Ferry President Ferry and Associates Architects DSS Organizati onal Consulti ng Graphic Design and Content Layout Tiff any Yates, Ph.D Sara Ratcliff e President Dacite, LLC Zoo Photographic Credits Robert Pinkston Jackie Peeler Shelley Lutes Kim Alexander Master Plan Executive Summary The Henson Robinson Zoo began as just a dream of a prominent Springfield citizen by the name of Henson C. Robinson. In 1967, a tract of land was donated to the Springfield Park District by the city of Springfield to fulfill his dream. Construction of the zoo began in 1968 and on August 29, 1970, the Henson Robinson Zoo was officially opened. Over the years, the zoo has grown and expanded with the addition of several new animals as well as exhibits. The zoo is now home to more than 300 animals native to Australia, Africa, Asia and North and South America. Over 90 species of native and exotic animals are housed here among naturalistic exhibits. -

South Mountain Reservation, Essex County, NJ 06.01.2020

Statement of the National Association for Olmsted Parks Opposing Plans for Development in South Mountain Reservation Essex County is the home of the first county-wide park system designed by the Olmsted firm. This jewel of Olmsted design – celebrating its 125th anniversary in 2020 – provides restorative green and open space across diverse communities in a densely populated area. In these challenging times, open green space has never been more important to the health and beauty of the entire community. Rather than focusing on a new pavilion to accommodate large crowds at the Turtle Back Zoo, the National Association for Olmsted Parks urges the County to prioritize the long-term health of the South Mountain Reservation through maintenance, conservation and preservation of its native flora and fauna and natural lands. ***** Background John Charles Olmsted supplied Essex County with the first South Mountain designs in June 1900. In addition to parks of various sizes to meet neighborhood needs, the firm planned several large reservations in the Essex County System to protect their unique natural scenery for the benefit and health of all county residents. Olmsted presented planting notes, detailing woodland improvements and plans for minimally intrusive roads and paths in South Mountain. The extensive collection of designs, photographs and correspondence in the Olmsted Archives and at the Library of Congress reveal comprehensive long-term plans for a healthy wooded reservation, largely free of development. In 1920, the Essex County Park Commission even issued bonds, valued at $500,000, to allow for the purchase of additional parcels. The property, writes local historian Jeanne Kolva, was needed “to prevent the erection of structures which would appear to the casual observer to be within the reservation itself, and thus greatly detract from its sylvan beauty.” (Olmsted Parks in New Jersey, 2011) In the original Olmsted plans, there was no Turtle Back Zoo. -

Summer 2019 Photo of the Season!

Summer 2019 Upcoming Events: pg. 1 Conservation Education: pg. 2 Donor Spotlight: pg. 4 Zoo News: pg. 5 Photo of the Season! Docent Randy Keenan To be considered for Visitor Photo of the Season, please send photos to [email protected] UPCOMING EVENTS Behind-the-Scenes Sea Lion Tours Saturdays and Sundays in May Something’s fishy! Behind-the-Scenes sea lion Nature Adventurers tours return on Saturdays and Sunday in May! For June 9 @1pm ages 6+. Register here: http://bit.ly/2GzTz35. Rain or shine, join our Nature Play Leader for an outdoor adventure! Stay Family Fun Nights tuned to register: http://bit.ly/2XDVpWB. Wednesdays and Thursdays in July and August Family Fun Nights return this summer! Admission Brew at the Zoo required to enter the zoo. Visit our zoo after Saturday, June 29 @6pm hours and then catch a “Zoo-vie” on Wednesday Essex County Turtle Back Zoo and the Zoological nights! Stay tuned here: http://bit.ly/2vmMAEd. Society of New Jersey will celebrate the park’s 56th Birthday by hosting the 7th Annual Brew Night Moves at the Zoo on June 29, 2019 from 6:00PM - 9:00 May 16 @7:30pm, more dates coming soon. PM. The festival will feature live entertainment, Evening guided tour of zoo. Learn about animal an abundance of brewers and vendors, and senses and adaptations. Register here: bit.ly/ a selection of over 100 craft beers For more nightmoves2019. information, please visit https://bit.ly/2UAaHtv. TBZ Summer Camp July through August Each camp is one week, ages 5-14. -

Custom Stainless Steel and Aluminum Fabrication for the Animal Industry

CONNECT October 2013 FEATURES 8 INTEGRATING COOPERATIVE BUYING INTO YOUR PURCHASING STRATEGY TOM ROGERS 12 CREATIVITY CREATES ADDITIONAL REVENUE ANNE SHIMERDLA 16 CHANGING TO A FISCAL YEAR Festival Lights the Way RAYMOND ULRICH 20 HARPY EAGLE PROJECT - PANAMA RON MAGILL 24 JAVAN WARTY PIG Conservation & Recovery JEFF HOLLAND 53 CEF UPDATE 2013 Conservation Endowment Fund Awards IN EVERY ISSUE 3 A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO 6 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH 29 MEMBER NEWS 33 CONSERVATION SPOTLIGHT 36 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD 37 BIRTHS & HATCHINGS 45 GREEN TALES 46 EXHIBITS ON THE COVER A young eagle, hatched at Zoo Miami, is now in a huge free flight aviary in Panama, 49 ANNOUNCEMENTS surrounded by pristine tropical forests where she is often visited by wild sloths, 54 MEMBER UPDATES monkeys, agoutis, parrots and toucans. She has become the face of her species for an entire country and hopefully will be paired up one day with a mate representing a new 57 INDEX OF ADVERTISERS bloodline where she can successfully reproduce and make invaluable contributions to 58 CALENDAR the Harpy Eagle Species Survival Plan® (SSP). HARPY EAGLE © RON MAGILL, ZOO MIAMI Designs for Life From concept through completion, to troubleshooting and retrotting existing systems, public zoos and aquariums worldwide have trusted Pentair’s WaterLife Design Group. Contact us today to nd out how we can help you. Web: WaterLifeDesign.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 407-472-0525 • Fax: 407-886-1304 2395 Apopka Blvd., Apopka, FL 32703 Find us on WaterLife Design Group is now a proud member of the Pentair family. -

2021 Spring Break Activities Copy

2021 Spring Break Family Guide Jointly produced by Woodbridge Township Recreation Department and Woodbridge Township Board of Education, the following list of activities and resources is for your family’s consideration during this year’s COVID-impacted Spring Break. All of these family-friendly activities are right here in New Jersey and many are low-cost or free. We hope you enjoy your well-deserved break. Woodbridge: Woodbridge Township Youth Services The Woodbridge Community Center will be holding School’s Out Camp from Monday April 5th through Friday April 9th. Campers will have access to the facility’s amenities such as the gym, indoor swimming pool, mini golf, and video game lounges. The camp day runs from 7:00 am – 6:30 pm and registration is $45 dollars per day. Registration forms can be found on the WCC Camp’s website at http://njwcc.com/737/Summer-Camp . For any further information, please contact D’Aisha Smith at 732-596-4181. Woodbridge Community Center The following facilities are open: Skyline Mini Golf & Batting Cages • Easter Special - Saturday, April 3rd • Open Friday, April 2 thru April 9th (Closed Easter Sunday, April 4) • Daily hours are Noon to 9:00 PM; Weekends open until 10:00 AM • See attached flyer for more details. • $3.00 children under 18 • $5.00 adults Roller Skating • Saturday, April 3 – Noon - 5:00 PM • $9.00 Child • $10.00 Adult • $5.00 skate rental Woodbridge Public Library Virtual Children, Teen and Adult programs. Learn more at www.Woodbridgelibrary.org. Browsing and borrowing in person are limited to the Main Library location. -

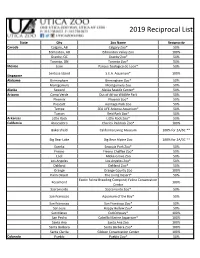

Utica Zoo Reciprocal List 2019

ZOO NAME ZOO ADDRESS RECIPROCITY Canada Calgary Zoo 210 St. George's Drive NE, Calgary, AB T2E 7V6, Canada 50% Granby Zoo 1050 Boulevard David-Bouchard N, Granby, QC J2H 0Y6, Canada 50% Toronto Zoo 2000 Meadowvale Road, Toronto, ON M1B 5K7, Canada 50% Edmonton Valley Zoo 13315 Buena Vista Road & 87th Avenue, Edmonton, AB T5J 2R7, Canada 100% Alabama Birmingham Zoo 2630 Cahaba Road, Birmingham, AL 35223 50% Montgomery Zoo 2301 Coliseum Pkwy, Montgomery, AL 36110 50% Alaska Alaska SeaLife Center 301 Railway Avenue, Seward, AK 99664 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 455 N Galvin Parkway, Phoenix, AZ 85008 50% SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 5000 S Arizona Mills Cir #145, Tempe, AZ 85285 50% Reid Park Zoo 3400 E Zoo Ct, Tucson, AZ 85716 50% Heritage Park Zoo 1403 Heritage Park Rd, Prescott, AZ 86301 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo 1 Zoo Drive, Little Rock, AR 72205 50% California Gibbon Conservation Center 19100 Esguerra Rd, Santa Clarita, CA 91390 100% Charles Paddock Zoo 9305 Pismo Avenue, Atascadero, CA 93422 100% Sequoia Park Zoo 3414 W Street, Eureka, CA 95503 50% Fresno Chaffee Zoo 894 W Belmont Avenue, Fresno, CA 93728 50% Los Angeles Zoo 5333 Zoo Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90027 50% Oakland Zoo 9777 Golf Links Road, Oakland, CA 94605 50% The Living Desert 47900 Portola Avenue, Palm Desert, CA 92260 50% Sacramento Zoo 3930 W Land Park Drive, Sacramento, CA 95822 50% Aquarium of the Bay Pier 39 The Embarcadero & Beach Street, San Francisco, CA 94133 50% San Fransisco Zoo Sloat Blvd & Great Highway, San Fransisco, CA 94132 50% Happy Hollow Zoo 748 Story Road, -

City of Roanoke, Virginia

City of Roanoke, Virginia Adopted Budget Fiscal Year 2016-2017 INTRODUCTION GFOA Award 1 VA Senator Mark Warner's Acknowledgement 2 City Council 3 Organizational Chart 4 Budget Committee 5 CITY MANAGER'S MESSAGE Letter of Transmittal 7 Budget Overview 12 Fee Adjustments 19 CITIZEN'S GUIDE Budget Process 21 Budget Preparation Calendar 24 Operating Funds Structure 25 Financial Guidelines & Policies 30 ABOUT OUR CITY General Information 43 City of Roanoke Quick Glance 55 Roanoke Metropolitan Area Quick Glance 56 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Overview 58 Roanoke in 2020 61 FINANCIAL SUMMARY Revenue & Expenditure Summary 67 Revenue Detail 68 Expenditure Detail 69 Fund Balance Comparison Revenue & Expenditure Comparisons General Fund 83 Enterprise Fund 88 Internal Service Fund 90 HUD Entitlement Grant 92 Fund Balance Analysis 93 PERSONNEL SUMMARY Overview 95 Staffing History 96 2016-2017 Pay Plan 99 Historical Trends 100 HUD CONSOLIDATION Overview 105 2016-2017 Recommended Projects 107 2016-2017 Funding Recommendations 111 PRIORITY SUMMARIES Priorities At-A-Glance 113 EDUCATION Strategy Map 115 Statement of Request for Results 116 Performance Indicators 126 Offer Ranking Sheet 131 Offer Executive Summary 132 SAFETY Strategy Map 137 Statement of Request for Results 138 Performance Indicators 144 Offer Ranking Sheet 148 Offer Executive Summary 150 HUMAN SERVICES Strategy Map 165 Statement of Request for Results 166 Performance Indicators 171 Offer Ranking Sheet 174 Offer Executive Summary 175 INFRASTRUCTURE Strategy Map 185 Statement of Request for Results -

2019 Utica Zoo Reciprocal List

2019 Reciprocal List State City Zoo Name Reciprocity Canada Calgary, AB Calgary Zoo* 50% Edmonton, AB Edmonton Valley Zoo 100% Granby, QC Granby Zoo* 50% Toronto, ON Toronto Zoo* 50% Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon* 50% Sentosa Island S.E.A. Aquarium* 100% Singapore Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo* 50% Montgomery Montgomery Zoo 50% Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center* 50% Arizona Camp Verde Out of Africa Wildlife Park 50% Phoenix Phoenix Zoo* 50% Prescott Heritage Park Zoo 50% Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium* 50% Tuscon Reid Park Zoo* 50% Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo* 50% California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo* 100% Bakersfield California Living Museum 100% for 2A/6C ** Big Bear Lake Big Bear Alpine Zoo 100% for 2A/3C ** Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo* 50% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo* 50% Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 50% Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo* 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo* 50% Orange Orange County Zoo 100% Palm Desert The Living Desert* 50% Exotic Feline Breeding Compund; Feline Conservation Rosamond 100% Center Sacramento Sacramento Zoo* 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay* 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo* 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo* 50% San Mateo CuriOdyssey* 100% San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium* 100% Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo 100% Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo* 100% Santa Clarita Gibbon Conservation Center 100% Colorado Pueblo Pueblo Zoo* 50% Connecticut Bridgeport Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo* 100% Delaware Wilmington Brandywine Zoo* 100% FREE- 10% discount in Washington DC Smithsonian National Zoological Park* gift shop -

For the Record Zoological Registrars Association Newsletter

FOR THE RECORD ZOOLOGICAL REGISTRARS ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER 2020 Issue 1 Feb – Mar 2020 In this issue BOARD OF DIRECTORS UPDATE What a whirlwind 2019 has been! I hope you’re all jumping in to 2020 with as much enthusiasm as you can muster after the holidays. Here’s to permit renewals and annual reports!! Board of Directors Update ............ 1 COMMITTEE UPDATES .................. 2 Over the last three months, the Board has reviewed, considered, Annual Conference 2019 Recap..... 2 edited and approved all the following: Bylaws Committee ........................... 3 Donations on behalf of ZRA in memory and support: History Committee ........................... 3 For Andrea Martin to Indianapolis Zoo Membership Services ...................... 3 For Alan Rost to the Endangered Primate Foundation Nominations and Elections For African Safari Wildlife Park to the Giraffe Conservation Committee ........................................ 3 Foundation Professional Development Committee Liaison confirmations: Committee ........................................ 3 Heather Terrell – Governance Committees Standards Committee ...................... 4 Joann Watson – Training, Standards, & Professional Development FARE THEE WELL, ALAN ............... 5 Jenn Wilson – Membership Services MEMBER NEWS ............................ 6 A first outside of Australia ............... 6 Committee Appointments Strategic Planning Priorities and Timelines Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo and IRK Scholarship was able to be awarded because of your votes! Aquarium Announces -

Groundhog Day History at Turtle Back Zoo E S D SE X E

THE SPIRIT OF EssexWINTER 2018 AM E F O H U S T Groundhog Day History at Turtle Back Zoo E S D SE X E R EDEFINING A GREAT PAGE 84 PAGE 105 PAGE 1520 PAGE 22EX17P ERIENC E Arts Joseph N. DiVincenzo, Jr. Essex County Executive AARON and the Board of NEVILLE Chosen Freeholders DUO SAT, JAN 12 AT 8PM Tickets: $58-$78 The unmistakable sound of Daniel K. Salvante Aaron Neville heard in legendary hits “Tell It Like It Is,” Director of Parks, Recreation “Don’t Know Much” and “Everybody Plays the Fool” and Cultural Affairs secure his spot as one of the great vocal stylists of all time. CHERISH GARLAND JOHN OATES INDEPENDENT THE LITTLE PUTTINGPUTTING ESSEX ESSEX COUNTY COUNTYTHE LADIES: JEFFREYS FIRST WIFIRSTTH THE VOICES: MERMEN CELTIC TRIO IN GOOD ROAD ALI SOUFAN A DISNEY COMPLIMENTARY ISSUE CHRISTMAS THE LOFT BAND THU, FEB 7 COVER BAND! COMPLIMENTARY ISSUE THU, DEC 20 FRI, DEC 28 FRI, JAN 4 AT 7:30PM SAT, FEB 23 AT 7:30PM AT 8PM AT 8PM Tickets: $30-$40 AT 8PM Tickets: $30-$40 Tickets: $25 Tickets: $40-$55 Former FBI investigator Tickets: $20 Beautiful vocals, Urban poet and Rock and Roll Hall of and anti-terrorism A live music show that captivating songster Garland Famer Oates turns to expert, leading national covers (in costume!) arrangements of Jeffreys mixes the sounds of the security expert Ali your favorite Disney traditional Celtic New Wave, Soul, heartland in his new Soufan will be tunes for a fun night of tunes and stunning Reggae, Garage release Arkansas.