Response to the Itamar Killings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 28N FebruaryS – 6 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 28 February – 6 March 2007 Of note this week The IDF imposed a total closure on the West Bank during the Jewish holiday of Purim between 2 – 5 March. The closure prevented Palestinians, including workers, with valid permits, from accessing East Jerusalem and Israel during the four days. It is a year – the start of the 2006 Purim holiday – since Palestinian workers from the Gaza Strip have been prevented from accessing jobs in Israel. West Bank: − On 28 February, the IDF re-entered Nablus for one day to continue its largest scale operation for three years, codenamed ‘Hot Winter’. This second phase of the operation again saw a curfew imposed on the Old City, the occupation of schools and homes and house-to-house searches. The IDF also surrounded the three major hospitals in the area and checked all Palestinians entering and leaving. According to the Nablus Municipality 284 shops were damaged during the course of the operation. − Israeli Security Forces were on high alert in and around the Old city of Jerusalem in anticipation of further demonstrations and clashes following Friday Prayers at Al Aqsa mosque. Due to the Jewish holiday of Purim over the weekend, the Israeli authorities declared a blanket closure from Friday 2 March until the morning of Tuesday 6 March and all major roads leading to the Old City were blocked. -

Yitzhar – a Case Study Settler Violence As a Vehicle for Taking Over Palestinian Land with State and Military Backing

Yitzhar – A Case Study Settler violence as a vehicle for taking over Palestinian land with state and military backing August 2018 Yitzhar – A Case Study Settler violence as a vehicle for taking over Palestinian land with state and military backing Position paper, August 2018 Research and writing: Yonatan Kanonich Editing: Ziv Stahl Additional Editing: Lior Amihai, Miryam Wijler Legal advice: Atty. Michael Sfard, Atty. Ishai Shneidor Graphic design: Yuda Dery Studio English translation: Maya Johnston English editing: Shani Ganiel Yesh Din Public council: Adv. Abeer Baker, Hanna Barag, Dan Bavly, Prof. Naomi Chazan, Ruth Cheshin, Akiva Eldar, Prof. Rachel Elior, Dani Karavan, Adv. Yehudit Karp, Paul Kedar, Dr. Roy Peled, Prof. Uzy Smilansky, Joshua Sobol, Prof. Zeev Sternhell, Yair Rotlevy. Yesh Din Volunteers: Rachel Afek, Dahlia Amit, Maya Bailey, Hanna Barag, Michal Barak, Atty. Dr. Assnat Bartor, Osnat Ben-Shachar, Rochale Chayut, Beli Deutch, Dr. Yehudit Elkana, Rony Gilboa, Hana Gottlieb, Tami Gross, Chen Haklai, Dina Hecht, Niva Inbar, Daniel A. Kahn, Edna Kaldor, Nurit Karlin, Ruth Kedar, Lilach Klein Dolev, Dr. Joel Klemes, Bentzi Laor, Yoram Lehmann RIP, Judy Lots, Aryeh Magal, Sarah Marliss, Shmuel Nachmully RIP, Amir Pansky, Talia Pecker Berio, Nava Polak, Dr. Nura Resh, Yael Rokni, Maya Rothschild, Eddie Saar, Idit Schlesinger, Ilana Meki Shapira, Dr. Tzvia Shapira, Dr. Hadas Shintel, Ayala Sussmann, Sara Toledano. Yesh Din Staff: Firas Alami, Lior Amihai, Yudit Avidor, Maysoon Badawi, Hagai Benziman, Atty. Sophia Brodsky, Mourad Jadallah, Moneer Kadus, Yonatan Kanonich, Atty. Michal Pasovsky, Atty. Michael Sfard, Atty. Muhammed Shuqier, Ziv Stahl, Alex Vinokorov, Sharona Weiss, Miryam Wijler, Atty. Shlomy Zachary, Atty. -

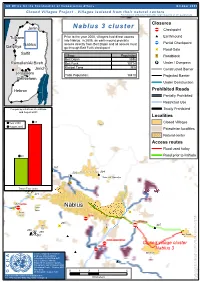

Nablus 3 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) Nablus 3 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm Prior to the year 2000, villagers had direct access Earthmound into Nablus. In 2005, an earthmound prohibits ¬Ç Nablus access directly from Beit Dajan and all access must Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya go through Beit Furik checkpoint D Road Gate Salfit Village Population /" Roadblock Beit Dajan 3696 Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Furik 10714 º¹P Under / Overpass Jericho Khirbet Tana N/A Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 14410 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Under Construction Hebron Prohibited Roads Partially ProhibitedTubas Restricted Use Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited ## and August 2005 Tubas Burqa Localities 45 Closed Villages Year 2000 Yasid August 2005 Beit Imrin Palestinian localities Natural center Nisf Jubeil Access routes Sabastiya Ijnisinya Road used today 290 # 358#20Shave Shomeron Road prior to Intifada ¬Ç An Naqura 287 ## 389 'Asira ash Shamaliya 294 # 293 # ## ## 288¬Ç beit iba 'Asira ash Shamaliya /" Qusin Travel Time (min) 271 D 270Ç SARRA Nablus D ¬ Sarra Sarra Sarra D Sarra ¬Ç At Tur 279 beit furik cp the of part the 265 D ÇÇ 297 Tell ¬¬ delimitation the concerning # Tell # 269 ## ## 296## 268 ## # Beit Dajan 266#267 ## awarta commercial cp ¬Ç Closed village cluster ¬Ç huwwara Nablus 3 ## Closure mapping is a work in Beit Furik progress. Closure data is collected by OCHA field staff and is subject to change. ## Maps will be updated regularly. Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian Information Centre - October 2005 Base data: 03612 O C H A O C H OCHA update August 2005 For comments contact <[email protected]> Tel. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Nablus City Profile

Nablus City Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 4102 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in the Nablus Governorate, and aim to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the programs and activities needed to mitigate the impact of the current insecure political, economic and social conditions in the Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Nablus Governorate. -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Palestine Divided

Update Briefing Middle East Briefing N°25 Ramallah/Gaza/Brussels, 17 December 2008 Palestine Divided I. OVERVIEW Hamas, by contrast, is looking to gain recognition and legitimacy, pry open the PLO and lessen pressure against the movement in the West Bank. Loath to con- The current reconciliation process between the Islamic cede control of Gaza, it is resolutely opposed to doing Resistance Movement (Hamas) and Palestinian National so without a guaranteed strategic quid pro quo. Liberation Movement (Fatah) is a continuation of their struggle through other means. The goals pursued by the The gap between the two movements has increased over two movements are domestic and regional legitimacy, time. What was possible two years or even one year together with consolidation of territorial control – not ago has become far more difficult today. In January national unity. This is understandable. At this stage, both 2006 President Abbas evinced some flexibility. That parties see greater cost than reward in a compromise quality is now in significantly shorter supply. Fatah’s that would entail loss of Gaza for one and an uncom- humiliating defeat in Gaza and Hamas’s bloody tac- fortable partnership coupled with an Islamist foothold tics have hardened the president’s and Fatah’s stance; in the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) for the moreover, despite slower than hoped for progress in other. Regionally, Syria – still under pressure from the West Bank and inconclusive political negotiations Washington and others in the Arab world – has little with Israel, the president and his colleagues believe incentive today to press Hamas to compromise, while their situation is improving. -

Zawata Village Profile

Zawata Village Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2014 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came about as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in the Nablus Governorate, and aim to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and present developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the programs and activities needed to mitigate the impact of the current insecure political, economic and social conditions in the Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Nablus Governorate. -

Palestinian Olive Agony 2018 ( a Statistical Report on Israeli Violations)

Palestinian Olive Agony 2018 ( A Statistical Report on Israeli Violations) Prepared by: Monitoring Israeli Violations Team Land Research Center Arab Studies Society - Jerusalem March 2019 ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY – Land Research Center (LRC) – Jerusalem 1 Halhul – Main Road, Tel: 02-2217239 , Fax: 02 -2290918 , P.O.Box: 35, E-mail: [email protected], URL: www.lrcj.org The olive tree have always been a thorn on the Israeli occupation’s side Deep rooted in the history of this land.. its oil is still sacred enlightening its temples Its branches play with farmers’ children.. and suffer from agonizing pain when touched by a settler’s saw That is, the Palestinian olive tree.. standing still on the face of the Israeli occupation’s sadism Burnt.. but reborn from its dust like a phoenix Cut.. but grows anew from its roots Stolen.. and when planted in their settlements. .becomes darkened and cloudy The Israeli occupiers tried to contain the olive tree , but it refused.. so they decided to uproot it from the land of Palestine , but failed and will fail The olive trees are a constant tar get by the occupation but they are still steadfast and refuses to surrender .. The olive tree stands for Palestinians' very existence, and their cultural identity and civilization, it is a testimony from history on the Palestinian land’s Arabism. Jamal Talab Al -Amleh LRC general manager Jerusalem – Palestine ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY – Land Research Center (LRC) – Jerusalem 2 Halhul – Main Road, Tel: 02-2217239 , Fax: 02-2290918 , P.O.Box: 35, E-mail: [email protected], URL: www.lrcj.org In 201 8, Land Research Center documented attacks that targeted olive trees, though daily monitoring: • 117 attacks took place , 90 of them were perpet rated by settlers from settlements nearby olive groves, while 27 were perpetrated by the occupation forces. -

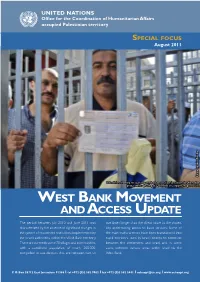

West Bank Movement Andaccess Update

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory SPECIAL FOCUS August 2011 Photo by John Torday John Photo by Palestinian showing his special permit to access East Jerusalem for Ramadan prayer, while queuing at Qalandiya checkpoint, August 2010. WEST BANK MOVEMENT AND ACCESS UPDATE The period between July 2010 and June 2011 was five times longer than the direct route to the closest characterized by the absence of significant changes in city, undermining access to basic services. Some of the system of movement restrictions implemented by the main traffic arteries have been transformed into the Israeli authorities within the West Bank territory. rapid ‘corridors’ used by Israeli citizens to commute There are currently some 70 villages and communities, between the settlements and Israel, and, in some with a combined population of nearly 200,000, cases, between various areas within Israel via the compelled to use detours that are between two to West Bank. P. O. Box 38712 East Jerusalem 91386 l tel +972 (0)2 582 9962 l fax +972 (0)2 582 5841 l [email protected] l www.ochaopt.org AUGUST 2011 1 UN OCHA oPt EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The period between July 2010 and June 2011 Jerusalem. Those who obtained an entry permit, was characterized by the absence of significant were limited to using four of the 16 checkpoints along changes in the system of movement restrictions the Barrier. Overcrowding, along with the multiple implemented by the Israeli authorities within the layers of checks and security procedures at these West Bank territory to address security concerns. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Palestinian Villages Affected by Violence from Yitzhar Settlement

¹º» United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory JANUARY 2012 JANUARY MONITOR HUMANITARIAN THE MONTHLY Palestinian Villages Affected by Violence SamaritanP! Village PALESTINIAN VILLAGES AFFECTED BY VIOLENCE FROM from Yitzhar Settlement and Outposts 'Iraq Burin YITZHAR SETTLEMENT AND OUTPOSTS P! ¥ TellP! February 2012 ?57 Gilad Farm P! •Population: 2,505 Bracha (Har Bracha) Khalet Alatot •Area: 6,440 dunums* (including 1,435 dunums in Area C) Bracha A RujeibP! •Village area inaccessible by Palestinians: 120 dunums KafrP! Qalil •Incidents in 2011: 8 incidents including two Palestinian casualties, damage to 67 olive trees and damage to Water well pipeline. •Population: 1,903 ?60 Legend •Area: 12,349 dunums* (including 9,811 dunums in Area C, Settlements Outpost Hill 778 almost 80% of the village) Madama Burin •Village area inaccessible?57 by Palestinian: 231 dunums Settlements Builtup Area P! P! •Main Incidents in 2011: 27 incidents, 36 Palestinian casualties, damage to 1850 olive trees, 100 almond trees Settlements Outerlimit Areas Affected by Settler Attack Settlement Municipal Boundary Israeli Military Base Sneh Ya'akov Palestinian Community Palestinian Local Authority Boundary 'Asira alP! Qibliya AREA A and B Beit Hanotzrim AREA (C) •Population: 900 Israeli settlers Shalhevet Estate, Yitzhar West •Established in 1983 on 18 dunums of land taken from Main Road ?57 Asira Al Qibliya village. Yitzhar •Today, the settlement outer limit covers 1800 dunums. Regional Road •Over 7500 dunums are mostly inaccessible to Local Road Palestinians due to settler violence. •In 2011, OCHA recorded 70 attacks by Yizhar settlers, the largest figure recorded from a single settlement this year.