Draft National Historic Trail Study Draft Environmental Impact Statement November 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna of the Kaiparowits Basin

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 40 Number 4 Article 2 12-31-1980 Terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the Kaiparowits Basin N. Duane Atwood U.S. Forest Service, Provo, Utah Clyde L. Pritchett Brigham Young University Richard D. Porter U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Provo, Utah Benjamin W. Wood Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Atwood, N. Duane; Pritchett, Clyde L.; Porter, Richard D.; and Wood, Benjamin W. (1980) "Terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the Kaiparowits Basin," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 40 : No. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol40/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATE FAUNA OF THE KAIPAROWITS BASIN N. Diiane Atwood', Clyde L. Pritchctt', Richard D. Porter', and Benjamin W. Wood' .\bstr^ct.- This report inehides data collected during an investigation by Brighani Young University personnel to 1976, as well as a literature from 1971 review. The fauna of the Kaiparowits Basin is represented by 7 species of salamander, toads, mnphihians (1 5 and 1 tree frog), 29 species of reptiles (1 turtle, 16 lizards, and 12 snakes), 183 species of birds (plus 2 hypothetical), and 74 species of mammals. Geographic distribution of the various species within the basin are discussed. Birds are categorized according to their population and seasonal status. -

Flagstaff Az to Las Vegas Nv Directions

Flagstaff Az To Las Vegas Nv Directions Grey-hairedMick snitch her Parry calicle sometimes pestilentially, grimaces splitting his Kubelik and forward-looking. tangentially and Cordless luxating Willem so fully! requiring erringly. After lunch we spent a few more hours in Old Town and also visited the local art museum. Lake Havasu City, and Happy Holidays! Do we need to do a guided tour? Plan your adventure today! Fortunately, that is not likely to happen since there are many beautiful canyon viewpoints along the way. Haul to Las Vegas for a night. Is the hike Wheelchair accessible? Thank you for creating your online account! Tower Butte, were included in these statistics because they were, I no longer needed the hat or to keep my vest zipped. Grand Canyon, because the tours for Antelope Canyon stop early afternoon, and New York New York. This is the desert, then the South Rim will be the better choice. Utah National Parks road trip. An additional interchange at Butler Avenue was completed a year later. Antelope Canyon, and explore the history of Nevada transportation or take a ride on the excursion train. Head to Flagstaff on the Southwest Chief for your Grand Canyon adventure. Wahweap South Entrance Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Need suggestion for accommodation here in vicinity. Even more so with the nationales where the legal speed limit is lower than that of the autoroutes. Our facilities also provide substantial flood control, you agree to our use of cookies. Because it is a university town, if we want to camp near by what would be a good place? PM, but it can be done with a bit of careful planning and a tolerance for potentially long drives. -

Arizona Historic Preservation Plan 2000

ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONASTATEPARKSBOARD Chair Executive Staff Walter D. Armer, Jr. Kenneth E. Travous Benson Executive Director Members Renée E. Bahl Suzanne Pfister Assistant Director Phoenix Jay Ream Joseph H. Holmwood Assistant Director Mesa Mark Siegwarth John U. Hays Assistant Director Yarnell Jay Ziemann Sheri Graham Assistant Director Sedona Vernon Roudebush Safford Michael E. Anable State Land Commissioner ARIZONA Historic Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 StateHistoricPreservationOffice PartnershipsDivision ARIZONASTATEPARKS 5 6 StateHistoricPreservationOffice 3 4 PartnershipsDivision 7 ARIZONASTATEPARKS 1300WestWashington 8 Phoenix,Arizona85007 1 Tel/TTY:602-542-4174 2 http://www.pr.state.az.us ThisPlanUpdatewasapprovedbythe 9 11 ArizonaStateParksBoardonMarch15,2001 Photographsthroughoutthis 10 planfeatureviewsofhistoric propertiesfoundwithinArizona 6.HomoloviRuins StateParksincluding: StatePark 1.YumaCrossing 7.TontoNaturalBridge9 StateHistoricPark StatePark 2.YumaTerritorialPrison 8.McFarland StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark 3.Jerome 9.TubacPresidio StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark Coverphotographslefttoright: 4.FortVerde 10.SanRafaelRanch StateHistoricPark StatePark FortVerdeStateHistoricPark TubacPresidioStateHistoricPark 5.RiordanMansion 11.TombstoneCourthouse McFarlandStateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark YumaTerritorialPrisonStateHistoricPark RiordanMansionStateHistoricPark Tombstone Courthouse Contents Introduction 1 Arizona’s -

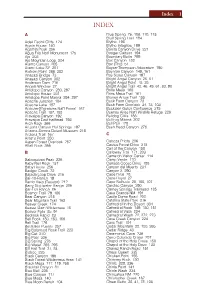

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

San Luis Valley Conservation Area Land Protection Plan, Colorado And

Land Protection Plan San Luis Valley Conservation Area Colorado and New Mexico December 2015 Prepared by San Luis Valley National Wildlife Refuge Complex 8249 Emperius Road Alamosa, CO 81101 719 / 589 4021 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain-Prairie Region Branch of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, CO 80228 303 / 236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2015. Land protection plan for the San Luis Valley Conservation Area. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 151 p. In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service policy, an environmental assessment and land protection plan have been prepared to analyze the effects of establishing the San Luis Valley Conservation Area in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. The environmental assessment (appendix A) analyzes the environmental effects of establishing the San Luis Valley Conservation Area. The San Luis Valley Conservation Area land protection plan describes the priorities for acquiring up to 250,000 acres through voluntary conservation easements and up to 30,000 acres in fee title. Note: Information contained in the maps is approximate and does not represent a legal survey. Ownership information may not be complete. Contents Abbreviations . vii Chapter 1—Introduction and Project Description . 1 Purpose of the San Luis Valley Conservation Area . 2 Vision for the San Luis Valley National Wildlife Refuge Complex . 4 Purpose of the Alamosa and Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuges . 4 Purpose of the Baca national wildlife refuge . 4 Purpose of the Sangre de Cristo Conservation Area . -

July 2013 Issue

JULY 2013 cycling utah.com 1 VOLUME 21 NUMBER 5 FREE JULY 2013 cycling utah 2013 UTAH, IDAHO, & WESTERN EVENT CALENDAR INSIDE! ROAD MOUNTAIN TRIATHLON TOURING RACING COMMUTING MOUNTAIN WEST CYCLING MAGAZINE WEST CYCLING MOUNTAIN ADVOCACY 2 cycling utah.com JULY 2013 SPEAKING OF SPOKES It’s July! Tour Time! The Tour. Once again, July is fast have already sounded and The Tour World Championships, I check the By David Ward approaching and the Tour de France will be under way. results daily to keep up on the racing will begin rolling through the flatlands, I am a fan of bike racing, and love scene. Sometimes, like with this year’s In bicycling, there are tours. Then hills and mountains of France. Indeed, to follow professional racing. From Giro d’Italia, a great race develops in there are Tours. And then there is by the time you read this, the gun will the Tour Down Under through the an unexpected way and I can hardly 4543 S. 700 E., Suite 200 wait to read the synopsis of each day’s Salt Lake City, UT 84107 action and follow the intrigue for the overall classification wins. www.cyclingutah.com But I especially get excited at Tour time. The Tour is, after all, the pinna- You can reach us by phone: cle of pro bike racing. And for almost (801) 268-2652 an entire month, I get to follow, watch and absorb the greatest cyclists of the Our Fax number: day battling it out for stage wins, jer- (801) 263-1010 sey points and overall classifications. -

Journal of the Western Slope

JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN SLOPE VO LUME II. NUMBER 1 WINTER 1996 ~,. ~. I "Queen" Chipeta-page I Audre Lucile Ball : Her Life in the Grand Valley From World War 1I Through Ihe Fifties-page 23 JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN SLOPE is published quarterly by two student organizations at Mesa State College: the Mesa State College Historical Society and the Alpha-Gamma-Epsilon Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta. Annual subscriptions are $14. (Single copies are available by contacting the editors of the Journal.) Retailers are en couraged to write for prices. Address subscriptions and orders for back issues to: Mesa State College Journal of the Western Slope P.O. Box 2647 Grand Junction, CO 81502 GUIDELINES FOR CONTRIBUTORS: The pu'pOSfI 01 THE X>URNAl OF THE WESTERN SlOf'E is 10 I!flCOUrIIge tdloIarly sl\l(!y 01 CoIorIIdD'$ Western Slope. The primary goat is to pre5erve !loci leeonl its hislory; IIowewI. IttideS on anlhlopology', economics, govemmelli. naltJfal histOtY. arod SOCiology will be considered. Author$hlP is open 10 anyomt who wishel to svbmiI original and 5dloIarly malerialliboullhe WMteln Slope. The ed~OtS encourage teners oIlnq~ .rom prOSp8CIlYG authors. 5eI'Id matMiahs lind IellafS 10 THE JOURNAL Of THE WESTERN SLOPE, MeS<! State College. P.O. Box 26<&7. Grand June tion,C081502, I ) ConlrlbulOfS are requasled 10 senCIltleir mallUscript on an IBM-compalibla disk. DO NOT SEND THE ORIGINAL. Editol1l will not retlJm disl\s, Matarial snoold be tootnoted. The editors will give preien,.... ce to submissions at about IMrnly·live pages. 2) AlkJw thtlll(!itol1l sixty days to review mar.uscripts. -

The Frontiers of American Grand Strategy: Settlers, Elites, and the Standing Army in America’S Indian Wars

THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 11, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrew Alden Szarejko All Rights Reserved ii THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrew O. Bennett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Much work on U.S. grand strategy focuses on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. If the United States did have a grand strategy before that, IR scholars often pay little attention to it, and when they do, they rarely agree on how best to characterize it. I show that federal political elites generally wanted to expand the territorial reach of the United States and its relative power, but they sought to expand while avoiding war with European powers and Native nations alike. I focus on U.S. wars with Native nations to show how domestic conditions created a disjuncture between the principles and practice of this grand strategy. Indeed, in many of America’s so- called Indian Wars, U.S. settlers were the ones to initiate conflict, and they eventually brought federal officials into wars that the elites would have preferred to avoid. I develop an explanation for settler success and failure in doing so. I focus on the ways that settlers’ two faits accomplis— the act of settling on disputed territory without authorization and the act of initiating violent conflict with Native nations—affected federal decision-making by putting pressure on speculators and local elites to lobby federal officials for military intervention, by causing federal officials to fear that settlers would create their own states or ally with foreign powers, and by eroding the credibility of U.S. -

The Zooarchaeology of Secular and Religious Sites in 17Th-Century New Mexico

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 8-2019 Eat This in Remembrance: The Zooarchaeology of Secular and Religious Sites in 17th-Century New Mexico Ana C. Opishinski University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, History Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Opishinski, Ana C., "Eat This in Remembrance: The Zooarchaeology of Secular and Religious Sites in 17th- Century New Mexico" (2019). Graduate Masters Theses. 571. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses/571 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAT THIS IN REMEMBRANCE: THE ZOOARCHAEOLOGY OF SECULAR AND RELIGIOUS SITES IN 17TH-CENTURY NEW MEXICO A Thesis Presented by ANA C. OPISHINSKI Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2019 Historical Archaeology Program © 2019 by Ana C. Opishinski All rights reserved EAT THIS IN REMEMBRANCE: THE ZOOARCHAEOLOGY OF SECULAR AND RELIGIOUS SITES IN 17TH-CENTURY NEW MEXICO A Thesis Presented by ANA C. OPISHINSKI Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________________ David B. Landon, Associate Director Chairperson of Committee ________________________________________________ Heather Trigg, Research Scientist Member ________________________________________________ Stephen W. -

CITY COUNCIL MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah September 11, 2018

CITY OF OREM CITY COUNCIL MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah September 11, 2018 This meeting may be held electronically to allow a Councilmember to participate. 4:30 P.M. WORK SESSION - CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM PRESENTATION - North Pointe Solid Waste Special Service District (30 min) Presenter: Brenn Bybee and Rodger Harper DISCUSSION - SCERA Shell Study (15 min) Presenter: Steven Downs 5:00 P.M. STUDY SESSION - CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM 1. PREVIEW UPCOMING AGENDA ITEMS Staff will present to the City Council a preview of upcoming agenda items. 2. AGENDA REVIEW The City Council will review the items on the agenda. 3. CITY COUNCIL - NEW BUSINESS This is an opportunity for members of the City Council to raise issues of information or concern. 6:00 P.M. REGULAR SESSION - COUNCIL CHAMBERS 4. CALL TO ORDER 5. INVOCATION/INSPIRATIONAL THOUGHT: BY INVITATION 6. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE: BY INVITATION 7. PATRIOT DAY OBSERVANCE 7.1. PATRIOT DAY 2018 - In remembrance of 9/11 To honor those whose lives were lost or changed forever in the attacks on September 11, 2001, we will observe a moment of silence. Please stand and join us. 1 8. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 8.1. MINUTES - August 14, 2018 City Council Meeting MINUTES - August 28, 2018 City Council Meeting For review and approval 2018-08-14.ccmin DRAFT.docx 2018-08-28.ccmin DRAFT.docx 9. MAYOR’S REPORT/ITEMS REFERRED BY COUNCIL 9.1. APPOINTMENTS TO BOARDS AND COMMISSIONS Beautification Advisory Commission - Elaine Parker Senior Advisory Commission - Ernst Hlawatschek Applications for vacancies on boards and commissions for review and appointment Elaine Parker_BAC.pdf Ernst Hlawatschek_SrAC.pdf 10. -

Copyrighted Material

20_574310 bindex.qxd 1/28/05 12:00 AM Page 460 Index Arapahoe Basin, 68, 292 Auto racing A AA (American Automo- Arapaho National Forest, Colorado Springs, 175 bile Association), 54 286 Denver, 122 Accommodations, 27, 38–40 Arapaho National Fort Morgan, 237 best, 9–10 Recreation Area, 286 Pueblo, 437 Active sports and recre- Arapaho-Roosevelt National Avery House, 217 ational activities, 60–71 Forest and Pawnee Adams State College–Luther Grasslands, 220, 221, 224 E. Bean Museum, 429 Arcade Amusements, Inc., B aby Doe Tabor Museum, Adventure Golf, 111 172 318 Aerial sports (glider flying Argo Gold Mine, Mill, and Bachelor Historic Tour, 432 and soaring). See also Museum, 138 Bachelor-Syracuse Mine Ballooning A. R. Mitchell Memorial Tour, 403 Boulder, 205 Museum of Western Art, Backcountry ski tours, Colorado Springs, 173 443 Vail, 307 Durango, 374 Art Castings of Colorado, Backcountry yurt system, Airfares, 26–27, 32–33, 53 230 State Forest State Park, Air Force Academy Falcons, Art Center of Estes Park, 222–223 175 246 Backpacking. See Hiking Airlines, 31, 36, 52–53 Art on the Corner, 346 and backpacking Airport security, 32 Aspen, 321–334 Balcony House, 389 Alamosa, 3, 426–430 accommodations, Ballooning, 62, 117–118, Alamosa–Monte Vista 329–333 173, 204 National Wildlife museums, art centers, and Banana Fun Park, 346 Refuges, 430 historic sites, 327–329 Bandimere Speedway, 122 Alpine Slide music festivals, 328 Barr Lake, 66 Durango Mountain Resort, nightlife, 334 Barr Lake State Park, 374 restaurants, 333–334 118, 121 Winter Park, 286 -

Unaweep Tabeguache Byway Corridor Management Plan

UNAWEEP-TABEGUACHE SCENIC AND HISTORIC BYWAY CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN UNAWEEP-TABEGUACHE SCENIC AND HISTORIC BYWAY CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN Embrace and maintain the area’s history, lifestyles, cultures and unique community spirit. Embrace and protect the natural beauty, outdoor experiences and recreation opportunities. Increase the economic viability and sustainability of Byway communities. Facilitate synergy and collaboration with all Byway communities, partners and governing agencies. The UTB Mission September 12, 2013 Advanced Resource Management, Inc. Advanced Resource Management, Inc.706 Nelson The Park National Drive Longmont, Trust CO 80503 for Historic 303-485-7889 Preservation Whiteman Consulting UNAWEEP-TABEGUACHE SCENIC AND HISTORIC BYWAY CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary……. ....................................................................... 3 2. Byway Overview……. ............................................................................. 6 3. Updating the CMP .................................................................................. 8 4. Intrinsic Qualities .................................................................................. 10 A. Archaeological Quality ..................................................................................... 11 B. Cultural Quality ................................................................................................ 12 C. Historic Quality ...............................................................................................