Hutt Valley Activity Centre, Which Is a Special Unit for Disruptive Secondary School Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 CSW Basketball Handbook

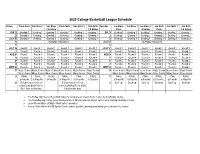

2020 College Basketball League Schedule Friday Prem Boys Sen Boys 1 Sen Boys Prem Girls Sen Girls 1 Sen Girls Tuesday Jun Boys Jun Boys 1 Jun Boys 2 Jun Girls Jun Girls 1 Jun Girls 2 & below 2 & below Prem & below Prem 2 & below JUN 19 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 JUN 16 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 Grading 1 26 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 23 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 Grading 2 JULY 03 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 30 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 Grading 3 10 SCHOOL HOLIDAYS JULY 07 SCHOOL HOLIDAYS 17 14 JULY 24 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 JULY 21 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 Round 1 31 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 28 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 Round 2 AUG 07 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 AUG 04 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 Round 3 14 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 11 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 Round 4 21 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 18 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 Round 5 28 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 25 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 Round 6 SEPT 04 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 SEPT 01 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 Round 7 11 Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis 08 Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis Major Semis -

2020 Futsal College Regionals | Senior Draw

COLLEGE SPORT WELLINGTON & CAPITAL FOOTBALL | 2020 FUTSAL COLLEGE REGIONALS | SENIOR DRAW Court 5/6 Court 7/8 Court 9/10 Court 11/12 Home Away Home Away Home Away Home Away 9:00 Wellington College Tawa College Aotea College Onslow College St Patrick's Town Naenae College Heretaunga College Hutt International 9:25 Rongotai College Wainuiomata High Hutt Valley High Kapiti College Scots College St Bernard's Upper Hutt St Pat's Silverstream 9:50 Wellington East Girls' Onslow College Queen Margaret HVHS Black Wellington Girls' HVHS White St Catherine's Sacred Heart 10:15 Onslow College Wellington College Tawa College Aotea College Hutt International St Patrick's Town Naenae College Heretaunga College 10:40 Kapiti College Rongotai College Wainuiomata High Hutt Valley High St Pat's Silverstream Scots College St Bernard's Upper Hutt 11:05 Queen Margaret Wellington East Girls' HVHS Black Onslow College St Catherine's Wellington Girls' Sacred Heart HVHS White 11:30 Tawa College Onslow College Wellington College Aotea College Naenae College Hutt International St Patrick's Town Heretaunga College 11:55 Wainuiomata High Kapiti College Rongotai College Hutt Valley High St Bernard's St Pat's Silverstream Scots College Upper Hutt 12:20 Onslow College Queen Margaret Wellington East Girls' HVHS Black HVHS White St Catherine's Wellington Girls' Sacred Heart 13:10 Boys Cup Quarter Final 1 (1st PA v 2nd PD) Boys Cup Quarter Final 2 (1st PB v 2nd PC) Boys Cup Quarter Final 3 (1st PC v 2nd PB) Boys Cup Quarter Final 4 (1st PD v 2nd PA) 13:35 Boys Plate Quarter -

Ministry of Health Contracted Adolescent Dental Providers

Ministry of Health Contracted Adolescent Dental Providers Wellington Capital Dental Whai Oranga Newtown 125-129 Riddiford Street Dental - Cuc Dang 7 The Strand, Wainuiomata Angela McKeefry Level 3, The Dominion 389 8880 564 6966 473 7802 Bldg, 78 Victoria Street Newtown Newtown Dental Jaideep Ben Catherwood Surgery Vijayasenan 1st Level 90 The Terrace 100 Riddiford Street 11 Queen Street, 472 3510 **(existing patients 389 3808 Wainuiomata Capital Dental The only) Ground Floor, Montreaux Adrian Tong Raine Street Dental, 4 Wellington CityWellington Terrace 939 9917 Building, 164 The Terrace 476 7295 Raine Street 499 9360 Karori Lumino Dental 180 Stokes Valley Road, Karori Dental 939 1818 Stokes Valley Dental Awareness Level 1, 9 Marion Street Centre 146 Karori Road 385 4386 Ashwin Magan 476 6451 Level 3, 84-90 Main Street Earle Kirton Harbour City Tower, 29 527 7914 Singleton Dental 473 7632 Brandon Street 294A Karori Road Christopher Allan 476 6252 U UUUU 22 Royal Street Irina Kvatch Central Dental Surgery, 139 Upper Hutt 528 5302 CODE Dental 220 Main Road 472 6306 Featherston Street Art of Dentistry 10 Royal Street 232 8001 Tawa 527 9437 Joanna Ora Toa Medical Hodgkinson Level 1, 90 The Terrace Michael Walton Centre 178 Bedford Street 22 Royal Street 472 3510 528 5302 237 5152 Navin Vithal Tennyson Dental Centre, Porirua Lumino Silverstream Village Shop The Dental Centre 801 6228 32 Lorne Street, Te Aro Silverstream 14/Cnr Whitemans Rd & Porirua 4 Lydney Place Peter Scott 528 3984 Kiln St 29 Brandon Street 237 6148 473 7632 Walter Szeto -

School Boy Vandalism in the Hutt Valley

SCHOOL BOY VANDALISM IN THE HUTT VALLEY PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS Occasional Papers in Criminology No. 8 ISSN 0110-1773 Michael Stace Institute of Criminology Victoria University of Wellington ' CON'l':t:N'l'8 Page Foreword L The Research Project Planning 1 Summary R 2. Preliminary Analysis A. Introduction 10 B. The Most Frequently Admitted Acts 12 C. Seriousness 18 D. Police Youth Aid Statistics 20 E • Summary 2 2 References 24 Appendix A 25 Appendix B 28 .FOREWORD An earlier Occasional Paper, namely Noc 6, February 1978, was written by Mr Michael Stace of this Institute on the subject of Vandalism and Self RepoEt Studies : A Review of the Literature. ':rhe present paper by Mr Stace gives some of the results from a questionnaire administered in four New Zealand post-primary schools, namely, the Hutt Valley High School, the Hutt Valley Memorial Technical College, Naenae College, and Taita College. We are 1m'.!eLted to Mr W. RAnwick, Director-General of Education tor the help and encouragement he and his senior officers 1;:rave to the launching of the project. We thank Mr E. Flaws, the Principal of Tawa College and Mr A. McLean, School Counsellor, for their helpful reception and adoption of the proposal that a pilot scheme be administered at Tawa College. We are also appreciative of the reception and support later given by the following principals of the four post-primary schools in the Hutt Valley and also the school counsellors as set out below;- School Principal Guidance Counsellor Hutt Valley High School M.r I. R. McLean Mr B.C. -

Hutt/Girls Zone Athletics

Newtown Park Stadium - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 6:14 AM 12/03/2021 Page 1 Hutt & Girls Zone Combined Athletics 2021 - 11/03/2021 Newtown Park Stadium, Wellimgton Results Event 114 Boys 100 Meter Run Junior Hutt Record: 11.28 2006 J Smith, Hutt International Name Age Team Finals Wind H# Finals 1 Austin-Aschebrock, Kaan Hutt Valley High School 12.91 -0.2 2 2 Foley, Lynkon Taita College 13.05 -0.2 2 3 Montgomery, Teina St Bernard's College 13.08 -0.2 2 4 Toluono, Lawrence St Bernard's College 13.44 -0.9 1 5 Reddy, Dishab Hutt Valley High School 13.47 -0.9 1 6 Zaballa, Inaki Hutt Valley High School 13.50 -0.9 1 7 Gonzalez Delgado, Jerson Naenae College 13.85 -0.2 2 8 Maligi-Masoe, Leo Naenae College 13.88 -0.9 1 9 West, Noah Hutt International Boys' 14.05 -0.2 2 10 Sheterline, Hamish Upper Hutt College 14.11 -0.2 2 11 Jacobs, James Hutt Valley High School 14.12 -0.9 1 12 Hickson, Oliver Hutt International Boys' 14.74 -0.9 1 Event 116 Boys 100 Meter Run Intermediate Hutt Record: 11.13 1991 R Morrell, Upper Hutt Name Age Team Finals Wind H# Finals 1 Moody, Tyrus Naenae College 12.14 1.1 3 2 Maluschnig, Ben St Bernard's College 12.16 1.1 2 3 Ranginui, Tamihana St Bernard's College 12.36 -0.9 1 4 Samuelu, Sam Naenae College 12.44 1.1 2 5 Urwin, Eli Heretaunga College 12.55 1.1 2 6 Foaese, Petonio Taita College 12.60 1.1 2 7 Haines, Rhone Heretaunga College 12.65 1.1 3 8 Baker, Matenga Naenae College 12.66 -0.9 1 9 Holden, Monty Hutt International Boys' 12.72 1.1 2 10 Bissielo, Eden Upper Hutt College 12.80 1.1 3 11 Armstrong, Luke Hutt -

Hutt Zone Athletics 2017 - 10/03/2017 Newtown Stadium Results

Newtown Park, Wellington - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 4:44 PM 10/03/2017 Page 1 Hutt Zone Athletics 2017 - 10/03/2017 Newtown Stadium Results Girls 100 Metre Run Junior Record: 12.50 R S Garden, Parkway Name Age Team Seed Finals Wind H# Points Finals 1 Foley, Stani Taita College 14.30 -0.7 3 5 2 Masson, Naomi Heretaunga College 14.34 -0.7 3 4 3 Vole, Ebony-Shavaugh Wainuiomata High School 14.78 -0.7 3 3 4 De Silva, Imali Hutt Valley High School 14.94 -1.6 1 2 5 McPartlin, Mikayla Heretaunga College 15.06 -2.1 2 1 6 Morresey, Camryn Hutt Valley High School 15.09 -0.7 3 7 McKean, Brooklyn Naenae College 15.39 -2.1 2 8 McQueen, Zoe Hutt Valley High School 15.44 -2.1 2 9 Jeffries-Rua, Jamiee Upper Hutt College 15.50 -2.1 2 10 Carter, Shanti Hutt Valley High School 15.66 -1.6 1 11 Pepere, Tiari Upper Hutt College 15.69 -0.7 3 12 Holland, Naomi Wa Ora Montessori School 15.98 -0.7 3 13 Leuila, Teila Taita College 16.07 -1.6 1 14 Arunkumar, Neha Wa Ora Montessori School 16.48 -2.1 2 15 Strickland, Una Wa Ora Montessori School 16.65 -1.6 1 Girls 200 Metre Run Junior Record: 26.50 R 1990 T Ioata, Naenae Name Age Team Seed Finals Wind H# Points Finals 1 Toa, Tamzin Wainuiomata High School 30.42 0.3 2 5 2 De Silva, Imali Hutt Valley High School 30.82 0.2 1 4 3 Keating, Hannah Hutt Valley High School 30.83 0.2 1 3 4 Vole, Ebony-Shavaugh Wainuiomata High School 30.94 1.0 3 2 5 Greville, Iona Heretaunga College 31.49 1.0 3 1 6 Morresey, Camryn Hutt Valley High School 31.78 1.0 3 7 Ioata, Destiny Naenae College 31.97 1.0 3 8 Esbach, Shaa-iqah -

Education Region (Total Allocation) Cluster Name School Name School

Additional Contribution to Base LSC FTTE Whole Remaining FTTE Total LSC for Education Region Resource (Travel Cluster Name School Name School Roll cluster FTTE based generated by FTTE by to be allocated the Cluster (A (Total Allocation) Time/Rural etc) on school roll cluster (A) school across cluster + B) (B) Coley Street School 227 0.45 Foxton Beach School 182 0.36 Foxton School 67 0.13 Kerekere Community of Learning 2 2 0 2 Manawatu College 309 0.62 Shannon School 73 0.15 St Mary's School (Foxton) 33 0.07 Chanel College 198 0.40 Douglas Park School 329 0.66 Fernridge School 189 0.38 Hadlow Preparatory School 186 0.37 Lakeview School 382 0.76 Makoura College 293 0.59 Masterton Intermediate 545 1.09 1 Mauriceville School 33 0.07 Opaki School 193 0.39 Masterton (Whakaoriori) Kāhui Ako 10 7 0 10 Rathkeale College 317 0.63 Solway College 154 0.31 Solway School 213 0.43 St Matthew's Collegiate (Masterton) 311 0.62 St Patrick's School (Masterton) 233 0.47 Tinui School 33 0.07 Wainuioru School 82 0.16 Wellington Wairarapa College 1,080 2.16 2 Whareama School 50 0.10 Avalon School 221 0.44 Belmont School (Lower Hutt) 366 0.73 Dyer Street School 176 0.35 Epuni School 93 0.19 Kimi Ora School 71 0.14 Naenae Community of Learning 5 4 0 5 Naenae College 705 1.41 1 Naenae Intermediate 336 0.67 Naenae School 249 0.50 Rata Street School 348 0.70 St Bernadette's School (Naenae) 113 0.23 Bellevue School (Newlands) 308 0.62 Newlands College 1,000 2.00 2 Newlands Intermediate 511 1.02 1 Newlands Community of Learning 5 2 0 5 Newlands School 310 0.62 Paparangi -

Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan Hearing 2021

Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan Hearing 20 April 2021, order paper - Front page If calling, please ask for Democratic Services Transport Committee - Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan Hearing 2021 Tuesday 20 April 2021, 9.30am Council Chamber, Greater Wellington Regional Council 100 Cuba Street, Te Aro, Wellington Members Cr Blakeley (Chair) Cr Lee (Deputy Chair) Cr Brash Cr Connelly Cr Gaylor Cr Hughes Cr Kirk-Burnnand Cr Laban Cr Lamason Cr Nash Cr Ponter Cr Staples Cr van Lier Recommendations in reports are not to be construed as Council policy until adopted by Council 1 Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan Hearing 20 April 2021, order paper - Agenda Transport Committee - Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan Hearing 2021 Tuesday 20 April 2021, 9.30am Council Chamber, Greater Wellington Regional Council 100 Cuba Street, Te Aro, Wellington Public Business No. Item Report Page 1. Apologies 2. Conflict of interest declarations 3. Process for considering the submissions and 21.128 3 feedback on the draft Wellington Regional Public Transport plan 2021 4. Analysis of submissions to the draft Wellington 21.151 7 Regional Public Transport plan 2021 2 Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan Hearing 20 April 2021, order paper - Process for considering the submissions andfeedback on the draf... Transport Committee 20 April 2021 Report 21.128 For Information PROCESS FOR CONSIDERING THE SUBMISSIONS AND FEEDBACK ON THE DRAFT WELLINGTON REGIONAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT PLAN 2021 Te take mō te pūrongo Purpose 1. To inform the Transport Committee (the Committee) of the process for considering submissions on the draft Wellington Regional Public Transport Plan 2021 (the draft RPTP). -

12/03/2020 Newtown Park Stadium, Wellington Results - TRACK EVENTS

Newtown Park Stadium - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 5:09 PM 12/03/2020 Page 1 College Sport Wellington Regional Championships 2020 - 12/03/2020 Newtown Park Stadium, Wellington Results - TRACK EVENTS Event 114 Boys 100 Meter Run Junior Record: 11.73 R 23/03/2017 Joshua Williams, Wgtn Coll Name Team Prelims Wind H# Preliminaries 1 Owen, Kyle Tawa College 12.34 q -1.2 1 2 Mallon, Ryan St Patrick's College Town 12.39 q 0.6 2 3 Lotsu, Joshua Kapiti College 12.58 q -1.2 1 4 Patterson, Henry Wellington College 12.64 q -1.2 1 5 Adam, Zayd Rongotai College 12.71 q 0.6 2 6 Jones, Richard Scots College 13.11 q 0.6 2 6 Patelesio-Galuo'meli, Vincent Bishop Viard College 13.11 q 0.6 2 8 Stenhouse, William St Patrick's College Town 13.13 q 0.6 2 9 Necklen, Fin Wellington High School 13.22 q 0.6 2 10 Taufao, Juleean Porirua College 13.30 -1.2 1 11 Whiripo, Justyn Tawa College 13.33 0.6 2 12 Miller, Bradley Kuranui College 13.35 -1.2 1 13 Kerkin, Foy Hutt Valley High School 13.36 0.6 2 14 Faitele, Wesley Taita College 13.52 -1.2 1 15 Samuelu, Sam Naenae College 13.57 -1.2 1 Event 114 Boys 100 Meter Run Junior Record: 11.73 R 23/03/2017 Joshua Williams, Wgtn Coll Name Team Prelims Finals Wind Finals 1 Owen, Kyle Tawa College 12.34 12.09 2.7 2 Mallon, Ryan St Patrick's College Town 12.39 12.20 2.7 3 Lotsu, Joshua Kapiti College 12.58 12.24 2.7 4 Patterson, Henry Wellington College 12.64 12.26 2.7 5 Patelesio-Galuo'meli, Vincent Bishop Viard College 13.11 12.42 2.7 6 Adam, Zayd Rongotai College 12.71 12.47 2.7 7 Stenhouse, William St Patrick's College -

Ministry of Health Contracted Adolescent Dental Providers

Ministry of Health Contracted Adolescent Dental Providers The Dental Studio Verve@Connolly Bdg, Wellington Newtown Dental Level 1, 2 Connolly Street Surgery 568 4006 Joanna 100 Riddiford Street 389 3808 I Care Dental Level 2 Mackay House Hodgkinson Level 1, 90 The Terrace 472 3510 560 3637 920 Queens Drive Capital Dental Ben Catherwood Newtown 1st Level 90 The Terrace Newtown 125-129 Riddiford Street ne 472 3510 Eastbourne Dental Cnr Marine Parade and 389 8880 Centre Capital Dental The bour Rimu Street, Eastbourne Ground Floor, Montreaux 562 7506 Terrace Adrian Tong Raine Street Dental Building, 164 The Terrace East 499 9360 476 7295 4 Raine Street Raymond Joe Capital Dental Karori Dental Dental Reflections 155 The Terrace Petone 272 Jackson Street, Petone Centre 146 Karori Road 472 5377 Petone 920 0880 Karori Karori 476 6451 Ferry Dental 155 The Terrace Singleton Dental Whai Oranga 472 5377 338 Karori Road 476 6252 Dental - Cuc Dang 7 The Strand, Wainuiomata Angela McKeefry Level 3, The Dominion Wainui 564 6966 473 7802 Bldg, 78 Victoria Street Khandallah Dental Irina Kvatch Central Dental Surgery, Centre 2 Ganges Road Lumino Dental 180 Stokes Valley Road, Wellington CityWellington 472 6306 139 Featherston Street 479 2294 alley Khandallah V 939 1818 Stokes Valley Navin Vithal Tennyson Dental Centre, S 32 Lorne Street, Te Aro CODE Dental 220 Main Road 801 6228 Ashwin Magan Victoria St Dental 232 8001 Tawa Level 3, 84-90 Main Street Level 6, 86 Victoria Street Tawa 527 7914 555 1001 The Dental Centre Art of Dentistry 10 Royal Street David -

Oia-1156529-SMS-Systems.Pdf

School Number School Name SMSInfo 3700 Abbotsford School MUSAC edge 1680 Aberdeen School eTAP 2330 Aberfeldy School Assembly SMS 847 Academy for Gifted Education eTAP 3271 Addington Te Kura Taumatua Assembly SMS 1195 Adventure School MUSAC edge 1000 Ahipara School eTAP 1200 Ahuroa School eTAP 82 Aidanfield Christian School KAMAR 1201 Aka Aka School MUSAC edge 350 Akaroa Area School KAMAR 6948 Albany Junior High School KAMAR ACT 1202 Albany School eTAP 563 Albany Senior High School KAMAR 3273 Albury School MUSAC edge 3701 Alexandra School LINC-ED 2801 Alfredton School MUSAC edge 6929 Alfriston College KAMAR 1203 Alfriston School eTAP 1681 Allandale School eTAP 3274 Allenton School Assembly SMS 3275 Allenvale Special School and Res Centre eTAP 544 Al-Madinah School MUSAC edge 3276 Amberley School MUSAC edge 614 Amesbury School eTAP 1682 Amisfield School MUSAC edge 308 Amuri Area School INFORMATIONMUSAC edge 1204 Anchorage Park School eTAP 3703 Andersons Bay School Assembly SMS 683 Ao Tawhiti Unlimited Discovery KAMAR 2332 Aokautere School eTAP 3442 Aoraki Mount Cook School MUSAC edge 1683 Aorangi School (Rotorua) MUSAC edge 96 Aorere College KAMAR 253 Aotea College KAMAR 1684 Apanui School eTAP 409 AparimaOFFICIAL College KAMAR 2333 Apiti School MUSAC edge 3180 Appleby School eTAP 482 Aquinas College KAMAR 1206 THEArahoe School MUSAC edge 2334 Arahunga School eTAP 2802 Arakura School eTAP 1001 Aranga School eTAP 2336 Aranui School (Wanganui) eTAP 1002 Arapohue School eTAP 1207 Ararimu School MUSAC edge 1686 Arataki School MUSAC edge 3704 -

Spaces for Hire

SPACES FOR HIRE A LIST OF SPACES FOR HIRE IN LOWER HUTT SPACES FOR HIRE CONTENTS ALICETOWN ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Transition Towns Community Centre ........................................................................................................... 5 AVALON.................................................................................................................................................. 5 Avalon Pavilion ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Avalon Public Hall ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Hutt Bridge Club ........................................................................................................................................... 6 St. John’s Avalon Uniting Church ................................................................................................................. 7 Ricoh Sports Centre ..................................................................................................................................... 7 BELMONT ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Belmont Memorial Hall (Belmont Domain) ..................................................................................................