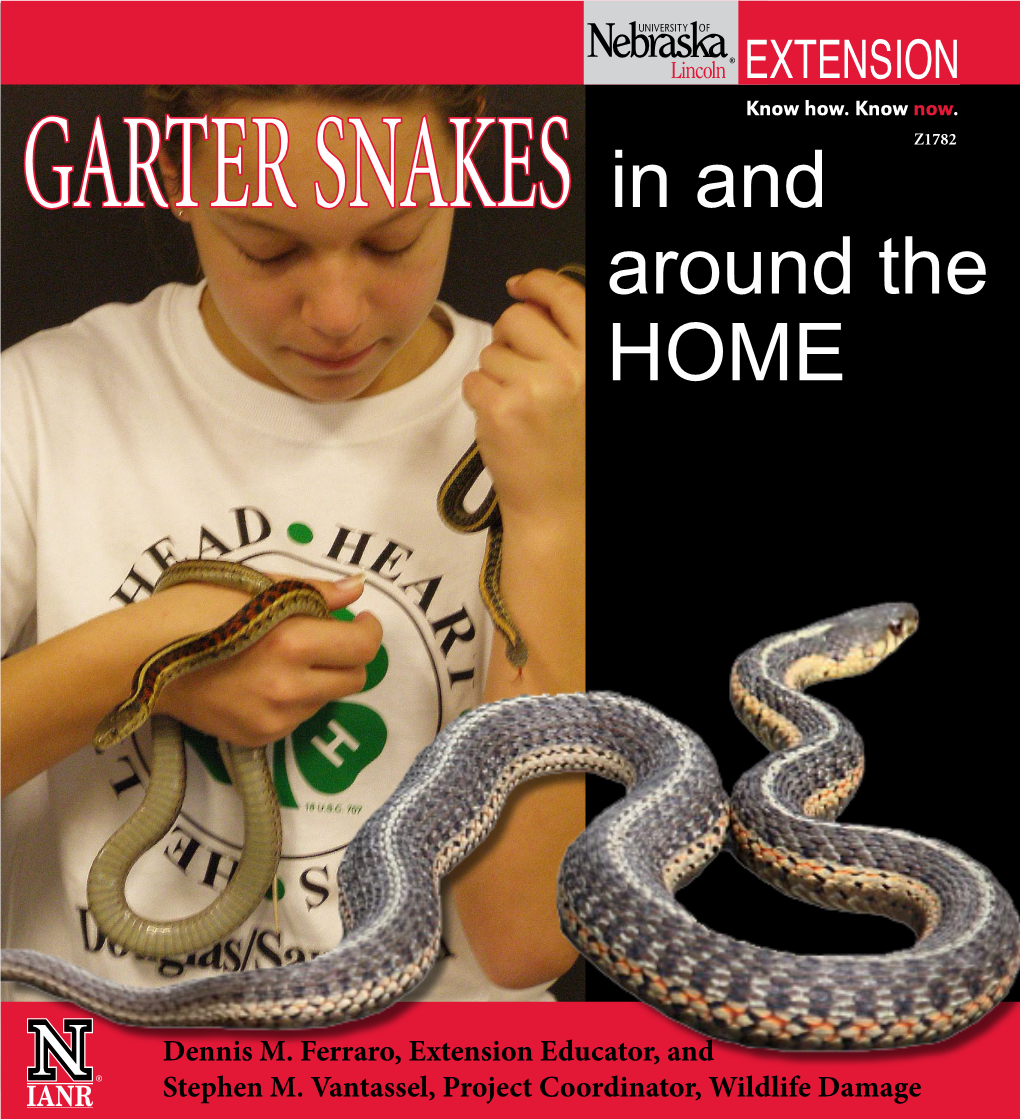

Garter Snakes in & Around the Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Creative Minds

For Creative Minds The For Creative Minds educational section may be photocopied or printed from our website by the owner of this book for educational, non-commercial uses. Cross-curricular teaching activities, interactive quizzes, and more are available online. Go to www.ArbordalePublishing.com and click on the book’s cover to explore all the links. Diurnal or Nocturnal Animals that are active during the day and asleep at night are diurnal. Animals that are active at night and asleep during the day are nocturnal. Read the following sentences and look for clues to determine if the animal is diurnal or nocturnal. A large dog sneaks up on The garter snake passes the skunk in the dark of the morning hunting night. The skunk stamps and basking in the warm her feet and throws her sunlight. If a predator tail up in the air. She arrives, he will hide his gives the other animal a head under some leaves warning before spraying. and flail his tail until it goes away. This bluebird is a The bright afternoon sun helpful garden bird. He helps this high-flying spends his days eating red-tailed hawk search insects off the plants and for her next meal. She defending his territory can see a grasshopper from other birds. from more than 200 feet (61m) away! As night falls, a small, The barn owl sweeps flying beetle with a over the field under glowing abdomen the dark night sky. emerges. She flashes her He flies slowly and light to signal to other silently, scanning the fireflies to come out. -

Wildlife Spotting Along the Thames

WILDLIFE SPOTTING ALONG THE THAMES Wildlife along the Thames is plentiful, making it a great location for birding. Bald Eagles and Osprey are regularly seen nesting and feeding along the river. Many larger birds utilize the Thames for habitat and feeding, including Red Tailed Hawks, Red Shoulder Hawks, Kestrels, King Fishers, Turkey Vultures, Wild Turkeys, Canada Geese, Blue Herons, Mallard Ducks, Black and Wood Ducks. Several species of owl have also been recorded in, such as the Barred Owl, Barn Owl, Great Horned Owl and even the Snowy Owl. Large migratory birds such as Cormorants, Tundra Swans, Great Egret, Common Merganser and Common Loon move through the watershed during spring and fall. The Thames watershed also contains one of Canada’s most diverse fish communities. Over 90 fish species have been recorded (more than half of Ontario’s fish species). Sport fishing is popular throughout the watershed, with popular species being: Rock Bass, Smallmouth Bass, Largemouth Bass, Walleye, Yellow Perch, White Perch, Crappie, Sunfish, Northern Pike, Grass Pickerel, Muskellunge, Longnose Gar, Salmon, Brown Trout, Brook Trout, Rainbow Trout, Channel Catfish, Barbot and Redhorse Sucker. Many mammals utilize the Thames River and the surrounding environment. White-tailed Deer, Muskrat, Beaver, Rabbit, Weasel, Groundhog, Chipmunk, Possum, Grey Squirrel, Flying Squirrel, Little Brown Bats, Raccoon, Coyote, Red Fox and - although very rare - Cougar and Black Bear have been recorded. Reptiles and amphibians in the watershed include Newts and Sinks, Garter Snake, Ribbon Snake, Foxsnake, Rat Snake, Spotted Turtle, Map Turtle, Painted Turtle, Snapping Turtle and Spiny Softshell Turtle. Some of the wildlife species found along the Thames are endangered making it vital to respect and not disrupt their sensitive habitat areas. -

Giant Garter Snake Habitat Quantification Tool

Giant Garter Snake Habitat Quantification Tool Part of the Multispecies Habitat Quantification Tool for the Central Valley Habitat Exchange Scientific Rationale and Methods Document, Version 5 Multispecies Habitat Quantification Tool: Giant Garter Snake Acknowledgements The development of the scientific approach for quantifying impacts and benefits to multiple species for use in the Central Valley Habitat Exchange (Exchange) would not have been possible without the input and guidance from a group of technical experts who worked to develop the contents of this tool. This included members of the following teams: Central Valley Habitat Exchange Project Coordinators John Cain (American Rivers) Daniel Kaiser (Environmental Defense Fund) Katie Riley (Environmental Incentives) Exchange Science Team Stefan Lorenzato (Department of Water Resources) Stacy Small-Lorenz (Environmental Defense Fund) Rene Henery (Trout Unlimited) Nat Seavy (Point Blue) Jacob Katz (CalTrout) Tool Developers Amy Merrill (Stillwater Sciences) Sara Gabrielson (Stillwater Sciences) Holly Burger (Stillwater Sciences) AJ Keith (Stillwater Sciences) Evan Patrick (Environmental Defense Fund) Kristen Boysen (Environmental Incentives) Giant Garter Snake TAC Brian Halstead (USGS) Laura Patterson (CDFW) Ron Melcer (formerly DWR; with Delta Stewardship Council as of February 2017) Chinook Salmon TAC Alison Collins (Metropolitan Water District) Brett Harvey (DWR) Brian Ellrott (NOAA/NMFS) Cesar Blanco (USFWS) Corey Phillis (Metropolitan Water District) Dave Vogel (Natural Resource -

Lesser Known Snakes (PDF)

To help locate food, snakes repeat- edly flick out their narrow forked tongues to bring odors to a special sense organ in their mouths. Snakes are carnivores, eating a variety of items, including worms, with long flexible bodies, snakes insects, frogs, salamanders, fish, are unique in appearance and small birds and mammals, and even easily recognized by everyone. other snakes. Prey is swallowed Unfortunately, many people are whole. Many people value snakes afraid of snakes. But snakes are for their ability to kill rodent and fascinating and beautiful creatures. insect pests. Although a few snakes Their ability to move quickly and are venomous, most snakes are quietly across land and water by completely harmless to humans. undulating their scale-covered Most of the snakes described bodies is impressive to watch. here are seldom encountered— Rather than moveable eyelids, some because they are rare, but snakes have clear scales covering most because they are very secre- their eyes, which means their eyes tive, usually hiding under rocks, are always open. Some snake logs or vegetation. For information species have smooth scales, while on the rest of New York’s 17 species others have a ridge on each scale of snakes, see the August 2001 that gives it a file-like texture. issue of Conservationist. Text by Alvin Breisch and Richard C. Bothner, Maps by John W. Ozard (based on NY Amphibian & Reptile Atlas Project) Artwork by Jean Gawalt, Design by Frank Herec This project was funded in part by Return A Gift To Wildlife tax check-off, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the NYS Biodiversity Research Institute. -

The Southern Watersnake (Nerodia Fasciata) in Folsom, California: History, Population Attributes, and Relation to Other Introduced Watersnakes in North America

THE SOUTHERN WATERSNAKE (NERODIA FASCIATA) IN FOLSOM, CALIFORNIA: HISTORY, POPULATION ATTRIBUTES, AND RELATION TO OTHER INTRODUCED WATERSNAKES IN NORTH AMERICA FINAL REPORT TO: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office 2800 Cottage Way, Room W-2605 Sacramento, California 95825-1846 UNDER COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT #11420-1933-CM02 BY: ECORP Consulting, Incorporated 2260 Douglas Blvd., Suite 160 Roseville, California 95661 Eric W. Stitt, M. S., University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources, Tucson Peter S. Balfour, M. S., ECORP Consulting Inc., Roseville, California Tara Luckau, University of Arizona, Dept. of Ecology and Evolution, Tucson Taylor E. Edwards, M. S., University of Arizona, Genomic Analysis and Technology Core The Southern Watersnake (Nerodia fasciata) in Folsom, California: History, Population Attributes, and Relation to Other Introduced Watersnakes in North America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 The Southern Watersnake (Nerodia fasciata)................................................................3 Study Area ....................................................................................................................6 METHODS ..........................................................................................................................9 Surveys and Hand Capture.............................................................................................9 Trapping.......................................................................................................................11 -

Class Reptilia

REPTILE CWCS SPECIES (27 SPECIES) Common name Scientific name Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii Broad-banded Water Snake Nerodia fasciata confluens Coal Skink Eumeces anthracinus Copperbelly Watersnake Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta Corn Snake Elaphe guttata guttata Diamondback Water Snake Nerodia rhombifer rhombifer Eastern Coachwhip Masticophis flagellum flagellum Eastern Mud Turtle Kinosternon subrubrum Eastern Ribbon Snake Thamnophis sauritus sauritus Eastern Slender Glass Lizard Ophisaurus attenuatus longicaudus False Map Turtle Graptemys pseudogeographica pseudogeographica Green Water Snake Nerodia cyclopion Kirtland's Snake Clonophis kirtlandii Midland Smooth Softshell Apalone mutica mutica Mississippi Map Turtle Graptemys pseudogeographica kohnii Northern Pine Snake Pituophis melanoleucus melanoleucus Northern Scarlet Snake Cemophora coccinea copei Scarlet Kingsnake Lampropeltis triangulum elapsoides Six-lined Racerunner Cnemidophorus sexlineatus Southeastern Crowned Snake Tantilla coronata Southeastern Five-lined Skink Eumeces inexpectatus Southern Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta dorsalis Timber Rattlesnake Crotalus horridus Western Cottonmouth Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma Western Mud Snake Farancia abacura reinwardtii Western Pygmy Rattlesnake Sistrurus miliarius streckeri Western Ribbon Snake Thamnophis proximus proximus CLASS REPTILIA Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii Federal Heritage GRank SRank GRank SRank Status Status (Simplified) (Simplified) N T G3G4 S2 G3 S2 G-Trend Decreasing G-Trend -

Amphibians and Snakes As Ruffed Grouse Food

Sept. 1951 200 THE WILSON BULLETIN Vol. 63. No. 3 Amphibians and snakes as Ruffed Grouse food.-In the extensive literature pertain- ing to the Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) there are .few references to the species’ eat- ing of snakes and amphibians. Bump et el. (1947. “The Ruffed Grouse,” pp: 191-192), Petrides (1949. Wilson Bulletin, 61: 49), and Findley (1950. ibid., 62: 133) have reported recent records of grouse eating Common Garter Snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) in New York, Michigan, and Minnesota, respectively. Chaddock (1940. “Report of the Ruffed Grouse, Pinnated Grouse and Sharp-tailed Grouse Crop Investigation,” Wisconsin Conservation Department mimeo- graphed bulletin) has reported finding a garter snake and a frog (Ram sp.), respectively, in the crops of two Ruffed Grouse shot in northern Wisconsin in the fall of 1939. Scott (1947. Auk, 64: 140) has reported tinding a small Red-bellied Snake (Stweria occipitomacda/a) in the crop of a RulIed Grouse collected in Taylor County, Wisconsin, in October, 1942. We wish to publish here two more interesting records for Wisconsin which came to light in 1950 during our Ruffed Grouse population studies for the Pittman-Robertson grouse re- search project (13-R) of the Wisconsin Conservation Department. A Ruffed Grouse collected September 20, 1950, in Forest County, Wisconsin, had an American Toad (Bufo americanus) in its crop. The toad was 96 mm. long (with legs extended), weighed 9.6 grams, and had been swallowed whole. The grouse, a male, weighed 552 grams, and showed no ill effects, either in behavior or in physical condition, from eating the toad. -

Notice Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions P.O

Publisher of Journal of Herpetology, Herpetological Review, Herpetological Circulars, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, and three series of books, Facsimile Reprints in Herpetology, Contributions to Herpetology, and Herpetological Conservation Officers and Editors for 2015-2016 President AARON BAUER Department of Biology Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085, USA President-Elect RICK SHINE School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney Sydney, AUSTRALIA Secretary MARION PREEST Keck Science Department The Claremont Colleges Claremont, CA 91711, USA Treasurer ANN PATERSON Department of Natural Science Williams Baptist College Walnut Ridge, AR 72476, USA Publications Secretary BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Notice warning concerning copyright restrictions P.O. Box 58517 Salt Lake City, UT 84158, USA Immediate Past-President ROBERT ALDRIDGE Saint Louis University St Louis, MO 63013, USA Directors (Class and Category) ROBIN ANDREWS (2018 R) Virginia Polytechnic and State University, USA FRANK BURBRINK (2016 R) College of Staten Island, USA ALISON CREE (2016 Non-US) University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND TONY GAMBLE (2018 Mem. at-Large) University of Minnesota, USA LISA HAZARD (2016 R) Montclair State University, USA KIM LOVICH (2018 Cons) San Diego Zoo Global, USA EMILY TAYLOR (2018 R) California Polytechnic State University, USA GREGORY WATKINS-COLWELL (2016 R) Yale Peabody Mus. of Nat. Hist., USA Trustee GEORGE PISANI University of Kansas, USA Journal of Herpetology PAUL BARTELT, Co-Editor Waldorf College Forest City, IA 50436, USA TIFFANY -

San Francisco Garter Snake, Thamnophis Sirtalis Tetrataenia

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office Species Account SAN FRANCISCO GARTER SNAKE Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia CLASSIFICATION: Endangered Federal Register 32:4001; March 1967 http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr18.pdf CRITICAL HABITAT: None designated RECOVERY PLAN: Final September 11, 1985 http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/850911.pdf In April 2005, 10 juvenile San Francisco garter snakes of five mixed gender pairs were transported from the Netherlands to the zoo. These ten snakes will be used as part of a public education effort that will include classroom visits from the Zoo Mobile, on-site presentations, inclusion in VIP tours and interpretive graphic displays, which are intended to inform local residents about the plight of the snake. DESCRIPTION: The San Francisco garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia) is a slender, colorful snake in the Colubridae family, which includes most of the species of snakes found in the western United States. This subspecies has a burnt orange head, greenish-yellow dorsal stripe edged in black, bordered by a red stripe, which may be continuous or broken with black blotches, and then a black stripe. The belly color varies from greenish-blue to blue. Large adults can reach 3 feet or more in length. Females give live birth from June through September, with litters averaging 16 newborn. The snakes are extremely shy, difficult to locate and capture, and quick to flee to water or cover when disturbed. The snakes' preferred habitat is a densely vegetated pond near an open hillside where they can sun themselves, feed, and find cover in rodent burrows; however, considerably less ideal habitats can be successfully occupied. -

Garter Snake Population Dynamics from a 16-Year Study: Considerations for Ecological Monitoring

Ecological Applications, 15(1), 2005, pp. 294±303 q 2005 by the Ecological Society of America GARTER SNAKE POPULATION DYNAMICS FROM A 16-YEAR STUDY: CONSIDERATIONS FOR ECOLOGICAL MONITORING AMY J. LIND,1 HARTWELL H. WELSH,JR., AND DAVID A. TALLMON2 USDA Forest Service, Paci®c Southwest Research Station, Redwood Sciences Laboratory, 1700 Bayview Drive, Arcata, California 95521 USA Abstract. Snakes have recently been proposed as model organisms for addressing both evolutionary and ecological questions. Because of their middle position in many food webs they may be useful indicators of trophic complexity and dynamics. However, reliable data on snake populations are rare due to the challenges of sampling these patchily distributed, cryptic, and often nocturnal species and also due to their underrepresentation in the eco- logical literature. Studying a diurnally active stream-associated population of garter snakes has allowed us to avoid some of these problems so that we could focus on issues of sampling design and its in¯uence on resulting demographic models and estimates. From 1986 to 2001, we gathered data on a population of the Paci®c coast aquatic garter snake (Thamnophis atratus) in northwestern California by conducting 3±5 surveys of the population annually. We derived estimates for sex-speci®c survival rates and time-dependent capture probabilities using population analysis software and examined the relationship between our calculated capture probabilities and variability in sampling effort. We also developed population size and density estimates and compared these estimates to simple count data (often used for wildlife population monitoring). Over the 16-yr period of our study, we marked 1730 snakes and had annual recapture rates ranging from 13% to 32%. -

Snakes of Berryessa

SNAKES OF BERRYESSA Introduction There are around 2700 Berryessa region, the Gopher Snake , yellow belly. Head snake species in the western rattlesnake, Pituophis roughly as thick as the world today. Of these, which is distinctly melanolancus: neck. The tail blunt like 110 species are different in Common. Up to the head. A live birthing indigenous to the United appearance from any 250 cm in length. constrictor. Nocturnal States. Here at Lake of our non-venomous Tan to cream dorsal during the summer. Berryessa, park visitors species. color with brown Found in coniferous have the opportunity to and black markings. forests under rocks and observe as many as Rattlesnakes pose no Dark line in front of logs, usually near a 10 different species serious threat to and behind the permanent source of of snakes. humans. The truth is, eyes. Diurnal water. Feeds on small in the entire United except for the mammals and lizards. Western Yellow Bellied Racer When observing snakes States only 10-12 California Kingsnake hottest portions of Gopher Snake in the wild, it's important Aquatic Garter Snake people die each year summer. Egg laying Western Yellow-Bellied Racer , Coluber constrictor : to follow certain due to snake bites, with 99% of these deaths attributed species that is found in almost any habitat. Can be Common. Up to 175 cm in length. guidelines. The fallen trees, stands of brush, and rock to either the western or eastern diamondback arboreal. Feeds on birds, lizards, rodents and eggs. Brown to olive skin with a pale yellow belly. Young piles found around Berryessa serve as homes, hunting rattlesnake, neither of which are found in the Berryessa Hisses loudly and vibrates it's tail when disturbed. -

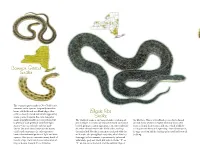

Snakes of New York State

Common Garter Snake ˜e common garter snake is New York’s most common snake species, frequently found in lawns, old ÿelds and woodland edges. One Black Rat of three closely related and similar appearing snake species found in the state, the garter Snake snake is highly variable in color pattern, but ˜e black rat snake is our longest snake, reaching six the blotches. ˜is is a woodland species, but is found is generally dark greenish with three light feet in length. Its scales are uniformly black and faintly around barns where it is highly desirable for its abil- stripes—one on each side and one mid- keeled, giving it a satiny appearance. In some individu- ity to seek and destroy mice and rats, which it kills by dorsal. ˜e mid-dorsal stripe can be barely als, white shows between the black scales, making coiling around them and squeezing. Around farmyards, visible and sometimes the sides appear to the snake look blotchy. Sometimes confused with the its eggs are o˛en laid in shavings piles used for livestock have a checkerboard pattern of light and dark milk snake, the young black rat snake, which hatches bedding. squares. ˜is species consumes many kinds of from eggs in late summer, is prominently patterned insects, slugs, worms and an occasional small with white, grey and black, but lacks both the “Y” or frog or mouse. Length: 16 to 30 inches. “V” on the top of the head, and the reddish tinge to Timber Rattlesnake Copperhead ˜e copperhead is an attractively-patterned, venomous snake with a pinkish-tan color super- imposed on darker brown to chestnut colored saddles that are narrow at the spine and wide at the sides.