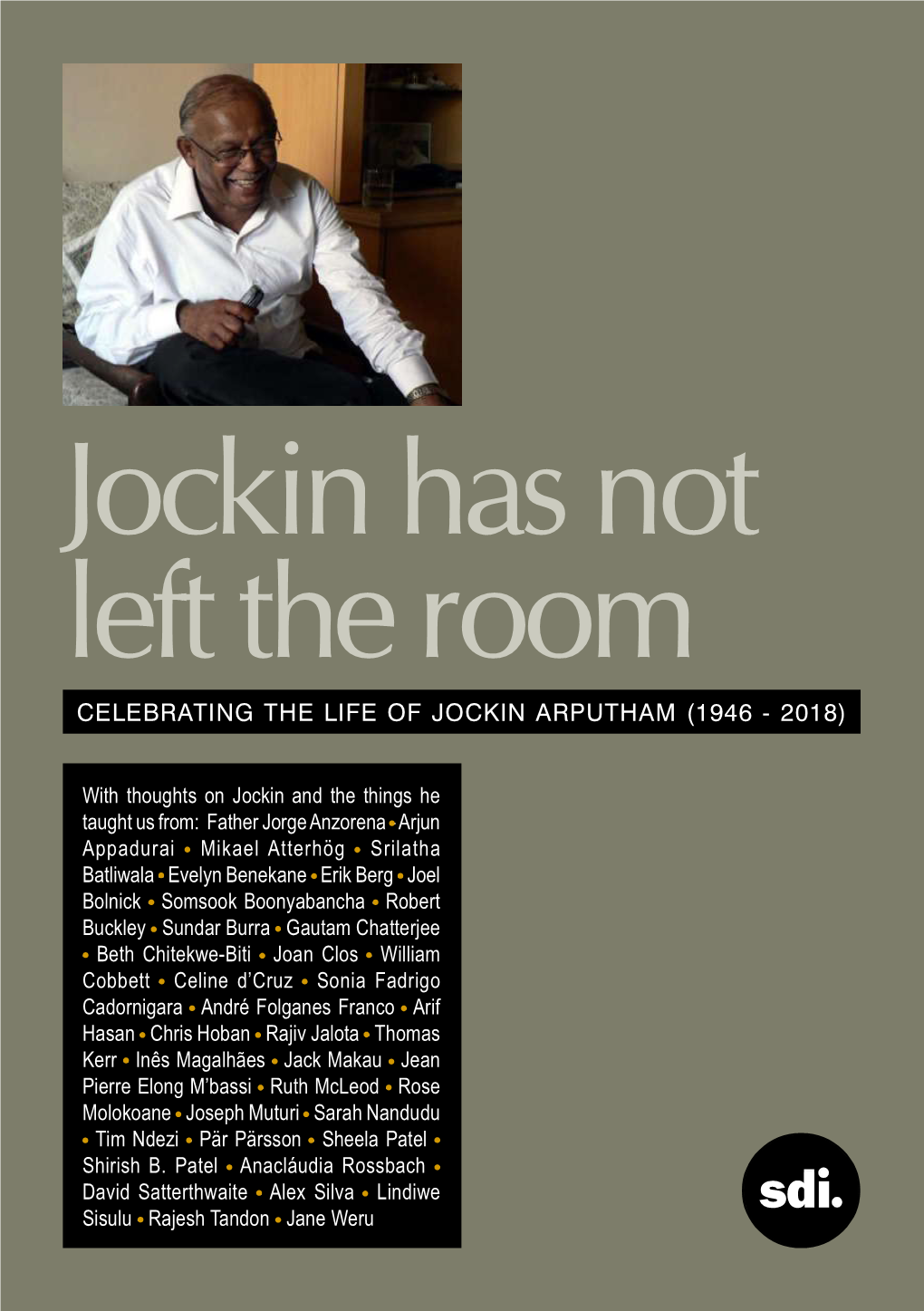

Celebrating the Life of Jockin Arputham (1946 - 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vividh Bharati Was Started on October 3, 1957 and Since November 1, 1967, Commercials Were Aired on This Channel

22 Mass Communication THE Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, through the mass communication media consisting of radio, television, films, press and print publications, advertising and traditional modes of communication such as dance and drama, plays an effective role in helping people to have access to free flow of information. The Ministry is involved in catering to the entertainment needs of various age groups and focusing attention of the people on issues of national integrity, environmental protection, health care and family welfare, eradication of illiteracy and issues relating to women, children, minority and other disadvantaged sections of the society. The Ministry is divided into four wings i.e., the Information Wing, the Broadcasting Wing, the Films Wing and the Integrated Finance Wing. The Ministry functions through its 21 media units/ attached and subordinate offices, autonomous bodies and PSUs. The Information Wing handles policy matters of the print and press media and publicity requirements of the Government. This Wing also looks after the general administration of the Ministry. The Broadcasting Wing handles matters relating to the electronic media and the regulation of the content of private TV channels as well as the programme matters of All India Radio and Doordarshan and operation of cable television and community radio, etc. Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC), which is a subordinate office, functions under the administrative control of this Division. The Film Wing handles matters relating to the film sector. It is involved in the production and distribution of documentary films, development and promotional activities relating to the film industry including training, organization of film festivals, import and export regulations, etc. -

Slum Dwellers International (SDI)

Slum Dwellers International (SDI) Skoll Entrepreneur(s): Jockin Arputham Award Year: 2014 Focus Area(s) Addressed: Education and Economic Opportunity, Water and Sanitation “Leading Slum Dwellers around the World to Improve Their Cities” In 2008—for the first time in history— more people were living in urban than in rural areas. Today, more than one billion people live in slums. Founded by a collective of slum dwellers and concerned professionals headed by Jockin Arputham, a community organizer in India, Slum Dwellers International works to have slums recognized as vibrant, resourceful, and dignified communities. SDI organizes slum dwellers to take control of their futures; improve their living conditions; and gain recognition as equal partners with governments and international organizations in the creation of inclusive cities. With programs in nearly 500 cities, including more than 15,000 slum dweller-managed savings groups reaching one million people; 20 agreements with national governments; and nearly 130,000 families who have secured land rights, SDI has been a driving force for change for slum dwellers around the world. Jockin Arputham is the president of the National Slum Dwellers Federation of India, which he founded in the 1970s. Often referred to as the “grandfather” of the global slum dwellers movement, Jockin was educated by the slums, living on the streets for much of his childhood with no formal education. For more than 30 years, Jockin has worked in slums and shanty towns throughout India and around the world. After working as a carpenter in Mumbai, he became involved in organizing the community where he lived and worked. -

Download Document In

Role Sharing and Collaboration between Governments and NGOs in National Development Dr. Jayaprakash Narayan National Coordinator LOK SATTA People Power India “Never doubt that a group of thoughtful, committed individuals can change the world.Indeed it is the only thing that ever did” Margaret Mead Voluntarism in India Two fountainheads – Charity (paramartha) – Service (seva) More an extension of religion What is missing A sense of common fate Trust in people’s capacity Sense of equality Early voluntarism Enlightened Christian missionaries (Religious) Ramakrishna Mission (Religious) Tagore’s Sriniketan in Bengal (Rural Development) Spencer Hatch of YMCA (Martandam, Kerala) (Rural Development) Voluntarism and social transformation Raja Rammohan Roy (Women’s upliftment) Iswarchandra Vidya Sagar (Women’s upliftment) Dayanand Saraswati (Religious reform and education) Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (Religious reform and education) Mahatma Jyotibha Phule (Fight against caste) Ramaswamy naicker (Tamilnadu) Narayana Guru (Kerala) Panduranga Sastry Athavale (Swadhyaya movement) Gandhian voluntary action Ambulance corps in South Africa (Boer war) Champaran – political struggle combined with constructive action Basic education Harijan welfare and removal of untouchability Sanitation Leprosy eradication (HLNS) Handlooms and Handicrafts Post-Independence India Government support to Gandhian concepts and Institutions Example: Harijan Seva Sangh Khadi and Village Industries Commission Khadi and Village Industries Board Sarvodaya movement -

SQUATTING RIGHTS Access to Toilets in Urban India in Sanskrit, Dasra Means Enlightened Givinging

SQUATTING RIGHTS Access to Toilets in Urban India In Sanskrit, Dasra means Enlightened Givinging. Dasra is Indiaís leading strategic philanthropy foundation. Dasra works with philanthropists and successful social entrepreneurs to bring together knowledge, funding and people as a catalyst for social change. We ensure that strategic funding and capacity building skills reach non profit organizations and social businesses to have the greatest impact on the lives of people living in poverty. www.dasra.org Omidyar Network is a philanthropic investment firm dedicated to harnessing the power of markets to create opportunity for people to improve their lives. Established in 2004 by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar and his wife Pam, the organization invests in and helps scale innovative organizations to catalyze economic and social change. To date, Omidyar Network has committed more than $500 million to for-profit companies and non-profit organizations that foster economic advancement and encourage individual participation across multiple investment areas, including microfinance, property rights, consumer internet, mobile and government transparency. www.omidyar.com Forbes Marshall is a leader in the area of process efficiency and energy conservation for the process industry. Since the inception of the company, sustainable social initiatives have been the key drivers of our philosophy to contribute and give back to the community in which we operate. Our diverse and sustained programs support health, education and life skills development in communities. We also help the community, particularly women, to engage in entrepreneurial ventures to support their families and thereby gain the skills and confidence in dealing with issues that impact their lives. Forbes Marshall has been ranked 5th among the top 25 “Best Workplaces” in India for the year 2012, by the Great Place to Work Institute® and The Economic Times. -

Jayaprakash Narayan: an Idealist Betrayed

Jayaprakash Narayan: An Idealist Betrayed M.G. DEVASAHAYAM Jayaprakash Narayan addressing a public meeting at Sitabdiara during a visit to his village on November 5, 1977. Photo: The Hindu Archives. The imposition of the Emergency in June 1975 by Indira Gandhi led to a general uprising across the country under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly known as JP. It also brought together strange bedfellows—the socialists and the Jan Sangh, the political face of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). In this personal epitaph on Jayaprakash Narayan, former civil servant M.G. Devasahayam, who was "the only person who had unrestricted access" to the late JP when he was prisoner during the Emergency, explains how the JP movement fizzled out due to what he terms the "betrayal of the RSS". Prelude The150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi commenced on October 2, 2018 with all solemnity and is being celebrated across the country. October 2 has become an iconic date known to even kindergarten kids. October 11 is the 116th birth anniversary of Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly known as JP. If Mahatma Gandhi is the architect of India’s first freedom in 1947, which was extinguished by Congress supremo Indira Gandhi on 25/26 June, 1975, it was JP who got us our second freedom after defeating Emergency in 1977. While Gandhiji won it from a tottering alien rule, JP had to take on and defeat the might of an entrenched domestic despot with vast resources and armed with draconian Emergency powers, reminiscent of Stalinist regime. In gratitude, common people called him the Second Mahatma. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government. -

HOMELESSNESS ABOUT BUTTERFLIES Children in News Homelessness

HOMELESSNESS ABOUT BUTTERFLIES Children in News Homelessness VOL. XXIV, 2015 HIS NAME IS TODAY Years V 1989 -2014 OL. XXIV , 2015 U-4, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 CHILDREN IN NEWS VOL XXIV, 2015 1 Tel.: 26163935, 26191063 E-mail: [email protected] Delhi Child Rights Club The Delhi Child Rights Club (DCRC) was launched by BUTTERFLIES in 1998. There was a need to have a children's forum in Delhi where children could articulate their issues and collectively take action to get their entitlements which is rightfully theirs. BUTTERFLIES invited children of NGOs working with children based in Delhi to be part of this forum. The response to this invitation was encouraging. Today there are children from 15 NGOs who are members In the little world in which and in recent times children from various neighbourhoods have attended DCRC meetings. The primary objective of DCRC is to have children's voices heard by civil society and policy makers, their views on issues children have their existence pertaining to their lives be taken seriously, and to consult them on all issues related to their welfare, development and protection. DCRC is open to all children of Delhi under 18 years of age whether from working whosoever brings them up,there is class, middle class or upper class background or a child living in an institution. A city-wide Child Rights Club is one mechanism where by children can work together towards the creation of a child safe and nothing so finely perceived and so friendly city. The children envisage a city where children's rights to respect, dignity, opportunities, growth, development and protection are ensured. -

Report of the Third Session of the World Urban Forum

UN-HABITAT REPORT OF THE THIRD SESSION OF THE WORLD URBAN FORUM VANCOUVER, CANADA JUNE 19-23, 2006 CONTENTS Page OVERVIEW........................................................................................................................5 I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................8 II. ORGANIZATIONAL MATTERS .................................................................................8 A. Attendance ..................................................................................................................8 B. Opening Ceremony .....................................................................................................9 C. Opening Plenary Session ............................................................................................9 D. Establishment of an Advisory Group .......................................................................10 E. Organization of Work ...............................................................................................11 F. Plenary Session 20 June 2006 ...................................................................................11 G. Special UN-Habitat Lecture .....................................................................................11 H. Plenary Session 21 June 2006 ..................................................................................11 I. Plenary Session 22 June 2006 ....................................................................................12 J. -

The Story of SDI President Jockin Arputham

Fr. Jorge Anzorena, SJ SELAVIP OCTOBER 2014 NEWSLETTER Journal of Low-Income Housing in Asia and the World Published with the generous aasistance of Misereor of Germany and the Jesuit East Asian Assistance by PAGTAMBAYAYONG FOUNDATION, Inc. 102 P. del Rosario Ext. Cebu City 6000 Philippines Fax. : [+63-32] 253 – 7974 Tel. : [+63-32] 418 - 2168 Email : [email protected] This publication is not covered by copyright and may be quoted or recopied in part or in full with or without acknowledgement or notice to its authors and publishers although such would be highly appreciated. About the Cover The sketch entitled "A Dream of Home" is by Raymund L. Fernandez, a socially oriented artist from Cebu City, Philippines. Raymund teaches art at the University of the Philippines and writes for the Cebu daily News. Many of his columns are featured in this and in previous issues. Raymund explains: “A house is every person's container of all that he or she dreams of and can dream about. It is the person himself or herself in the concrete, or of wood or bamboo or soil which constitute the safe space over which the person might build all his or her aspirations. Over these the person puts a roof to guard against the forces. The house is the beginning and end of the person. It is the primal unit from which we build the citizen, the citizenry and the nation.” Table of Content October 2014 NETWORK • The Decent Poor Program (2013-2014) 01 • Cambodia: Training on Settlement National Survey 01 • Extreme Poverty Europe, Posted by JESCO on October 19, 2013 02 • Arif Hasan on Pakistan and OPP 03 • Saying Goodbye to Father Bebot 03 • Fr. -

Jayaprakash Narayan's Thesis

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY April 9, 1960 partly explain why their investiga- ' The authors seem to be convinced debt to Hill, Stycos, Back and their tors were given answers which are that the medically preferred me many helpers. They have pioneer encouraging to the research work thods of contraception offered by ed a way into very difficult territory, ers. "Yes, we only want 2 child the clinics are essential for bringing and they have been good enough to ren", "Yes, we think your education down the birth rate. If this is their share their thinking processes as programme was fine". How much conviction they have overlooked the well as their data with all who take were these verbal answers checked fact that the birth rate in their own the trouble to read their book. Any by hard facts? Not enough. Pro and other Western countries has one who has had experience of this been brought down mostly by the bably also too much reliance was type of field work will appreciate; use of two such "inferior" methods how much labour has gone into this placed on answers given at one or as douching and withdrawal, with study. If they have not got all the very few interviews. People do not condom. The difference is that answers, neither has anyone else. usually reveal their true selves im people in the West not only said they They have shown the value of their mediately, and Puerto Ricans no wanted small families when asked approach and their method of work: doubt share with most ordinary by investigators but they were also that it also has weaknesses is under rural people an understanding of determined to have small families. -

Nominations for Padma Awards 2011

c Nominations fof'P AWARDs 2011 ADMA ~ . - - , ' ",::i Sl. Name';' Field State No ShriIshwarappa,GurapJla Angadi Art Karnataka " Art-'Cinema-Costume Smt. Bhanu Rajopadhye Atharya Maharashtra 2. Designing " Art - Hindustani 3. Dr; (Smt.).Prabha Atre Maharashtra , " Classical Vocal Music 4. Shri Bhikari.Charan Bal Art - Vocal Music 0, nssa·' 5. Shri SamikBandyopadhyay Art - Theatre West Bengal " 6: Ms. Uttara Baokar ',' Art - Theatre , Maharashtra , 7. Smt. UshaBarle Art Chhattisgarh 8. Smt. Dipali Barthakur Art " Assam Shri Jahnu Barua Art - Cinema Assam 9. , ' , 10. Shri Neel PawanBaruah Art Assam Art- Cinema Ii. Ms. Mubarak Begum Rajasthan i", Playback Singing , , , 12. ShriBenoy Krishen Behl Art- Photography Delhi " ,'C 13. Ms. Ritu Beri , Art FashionDesigner Delhi 14. Shri.Madhur Bhandarkar Art - Cinema Maharashtra Art - Classical Dancer IS. Smt. Mangala Bhatt Andhra Pradesh Kathak Art - Classical Dancer 16. ShriRaghav Raj Bhatt Andhra Pradesh Kathak : Art - Indian Folk I 17., Smt. Basanti Bisht Uttarakhand Music Art - Painting and 18. Shri Sobha Brahma Assam Sculpture , Art - Instrumental 19. ShriV.S..K. Chakrapani Delhi, , Music- Violin , PanditDevabrata Chaudhuri alias Debu ' Art - Instrumental 20. , Delhi Chaudhri ,Music - Sitar 21. Ms. Priyanka Chopra Art _Cinema' Maharashtra 22. Ms. Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry Art_ Theatre Chandigarh , ' ,I 23. Shri Jogen Chowdhury Art- Painting \VesfBengal 24.' Smt. Prafulla Dahanukar Art ~ Painting Maharashtra ' . 25. Ms. Yashodhara Dalmia Art - Art History Delhi Art - ChhauDance 26. Shri Makar Dhwaj Darogha Jharkhand Seraikella style 27. Shri Jatin Das Art - Painting Delhi, 28. Shri ManoharDas " Art Chhattisgarh ' 29. , ShriRamesh Deo Art -'Cinema ,Maharashtra Art 'C Hindustani 30. Dr. Ashwini Raja Bhide Deshpande Maharashtra " classical vocalist " , 31. ShriDeva Art - Music Tamil Nadu Art- Manipuri Dance 32. -

Cataracts of Silence

RACISM Durban, South Africa and PUBLIC 3 - 5 September 2001 POLICY Cataracts of Silence Race on the Edge of Indian Thought Vijay Prashad United Nations Research Institute for Social Development 2 The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Civil Society and Social Movements; Democracy, Governance and Human Rights; Identities, Conflict and Cohesion; Social Policy and Development; and Technology, Business and Society. A list of the Institute’s free and priced publications can be obtained by contacting the Reference Centre. UNRISD work for the Racism and Public Policy Conference is being carried out with the support of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. UNRISD also thanks the governments of Denmark, Finland, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom for their core funding. UNRISD, Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 9173020 Fax: (41 22) 9170650 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unrisd.org Copyright © UNRISD. This paper has not been edited yet and is not a formal UNRISD publication.