A Floral History of Australian Art’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Lempriere Mid-20Th Century Representations of Aboriginal Themes Gloria Gamboz

Helen Lempriere Mid-20th century representations of Aboriginal themes Gloria Gamboz The best-known legacy of the While living in Paris and London in half of the 20th century has created Australian painter, sculptor and the 1950s, Lempriere was influenced some contention, and these works are printmaker Helen Lempriere by anthropological descriptions of now being reinvestigated as part of (1907–1991) is the sculpture prize Australian Indigenous cultures, and a broader examination of emerging and travelling scholarship awarded in developed a highly personal and Australian nationhood. A study of her name. Less well known, however, expressive mode of interpretation Lempriere’s life, influences and key are her post–World War II works that blended Aboriginal themes with works provides an insight into the exploring Aboriginal myths, legends her own vision. The appropriation cultural climate of post–World War II and iconography. Twelve of these of Aboriginal themes by non- Australia, and the understanding of are held by the Grainger Museum Indigenous Australian women Aboriginal culture by non-Indigenous at the University of Melbourne, and artists like Lempriere in the first women artists. have recently been made available on the museum’s online catalogue.1 They form part of a wider collection of works both by, and depicting, Helen Lempriere, bequeathed by Lempriere’s husband, Keith Wood, in 1996.2 The collection is likely to have come to the Grainger Museum through a mutual contact, the Sydney- based curator, collector and gallery director Elinor -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

List of Works

4 JANUARY – 22 MARCH 2020 Margaret's Gift acknowledges and celebrates the generous legacy of Margaret Olley AC (1923-2011). Olley was a preeminent artist who had more than 90 solo exhibitions during her lifetime. Using funds from her own exhibition sales Olley would purchase fellow artists works, which she would then in turn donate to numerous galleries. She was also an entrepreneur who invested wisely in residential properties, that in turn brought in a steady income. This put her in a unique position in which she could, not only focus on her own artistic practice but she had the time and means to paint, travel, acquire and donate. The working relationships and life-long friendships she developed with gallery curators, directors and fellow artists are testament to her unwavering support of art and culture within this country. Throughout her lifetime, Olley continued to donate and provide funds to various institutions. This approach enabled institutions to acquire significant works of art. Many of these works are now considered collection highlights, spanning national, state, regional and university art collections. The Margaret Olley Art Trust was established in 1990. This legacy continues today, with the ongoing support of the trustees of the Margaret Olley Art Trust, through both donation of work or funds allocated to a specific project. This exhibition is the second in a series of three that has the generous support of the Margaret Olley Art Trust. Curated by Renée Porter, the exhibition presents over 60 works from collections in Queensland, New South Wales and the ACT and include works by European masters, Australian artists and ceramics from Papua New Guinea which were her earliest known gifts. -

Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA

arts Article Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA Marie Geissler Faculty of Law Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia; [email protected] Received: 19 February 2019; Accepted: 28 April 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: This paper explores how the appeal of the imagery of the Arnhem Land bark painting and its powerful connection to land provided critical, though subtle messaging, during the post-war Australian government’s tourism promotions in the USA. Keywords: Aboriginal art; bark painting; Smithsonian; Baldwin Spencer; Tony Tuckson; Charles Mountford; ANTA To post-war tourist audiences in the USA, the imagery of Australian Aboriginal culture and, within this, the Arnhem Land bark painting was a subtle but persistent current in tourism promotions, which established the identity and destination appeal of Australia. This paper investigates how the Australian Government attempted to increase American tourism in Australia during the post-war period, until the early 1970s, by drawing on the appeal of the Aboriginal art imagery. This is set against a background that explores the political agendas "of the nation, with regards to developing tourism policies and its geopolitical interests with regards to the region, and its alliance with the US. One thread of this paper will review how Aboriginal art was used in Australian tourist designs, which were applied to the items used to market Australia in the US. Another will explore the early history of developing an Aboriginal art industry, which was based on the Arnhem Land bark painting, and this will set a context for understanding the medium and its deep interconnectedness to the land. -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

Making 18 01–20 05

artonview art o n v i ew ISSUE No.49 I ssue A U n T U o.49 autumn 2007 M N 2007 N AT ION A L G A LLERY OF LLERY A US T R A LI A The 6th Australian print The story of Australian symposium printmaking 18 01–20 05 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra John Lewin Spotted grossbeak 1803–05 from Birds of New South Wales 1813 (detail) hand-coloured etching National Gallery of Australia, Canberra nga.gov.au InternatIonal GallerIes • australIan prIntmakInG • modern poster 29 June – 16 September 2007 23 December 2006 – 6 May 2007 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra National Gallery of Australia, Canberra George Lambert The white glove 1921 (detail) Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney purchased 1922 photograph: Jenni Carter for AGNSW Grace Crowley Painting 1951 oil on composition board National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 1969 nga.gov.au nga.gov.au artonview contents 2 Director’s foreword Publisher National Gallery of Australia nga.gov.au 5 Development office Editor Jeanie Watson 6 Masterpieces for the Nation appeal 2007 Designer MA@D Communication 8 International Galleries Photography 14 The story of Australian printmaking 1801–2005 Eleni Kypridis Barry Le Lievre Brenton McGeachie 24 Conservation: print soup Steve Nebauer John Tassie 28 Birth of the modern poster Designed and produced in Australia by the National Gallery of Australia 34 George Lambert retrospective: heroes and icons Printed in Australia by Pirion Printers, Canberra 37 Travelling exhibitions artonview ISSN 1323-4552 38 New acquisitions Published quarterly: Issue no. 49, Autumn 2007 © National Gallery of Australia 50 Children’s gallery: Tools and techniques of printmaking Print Post Approved 53 Sculpture Garden Sunday pp255003/00078 All rights reserved. -

ANSWERS to QUESTIONS on NOTICE Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Office of the Official Secretary to the Governor-General

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee 2005-06 Supplementary Budget Hearings ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Office of the Official Secretary to the Governor-General QUESTION: PM1 Senator Crossin asked: “..How many times this year has a government member represented the Governor- General and given a message on his behalf?” QUESTION: PM2 Senator Crossin asked: “… At Uluru—Ayers Rock. It was the 20th anniversary of the hand back. You probably do not have the answer with you but can you take on notice who invited the Governor-General to that?” QUESTION: PM3 Senator Crossin asked: “…Can you also please take on notice for me whom his message was given to and why?” QUESTION: PM4 Senator Crossin asked: “In an instance where the Governor-General cannot attend, is there any protocol that suggests that the message should be given to the House of Representatives member to read out rather than to some other member of parliament? …. Could you have a look at that, please, and answer this question: if the government is the body issuing the invitation and the Governor-General is unable to go, is it custom and practice that the local House of Representatives member reads the Governor-General’s message rather than anybody else?” Response: The response to Senator Crossin’s questions PM1 to PM4 is set out below. There is no written protocol or guideline for how the Governor-General is to be represented at an event or function that he is unable to attend. Messages are not sent to the Governor or Administrator of a State or Territory unless it was they who had invited the Governor-General. -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

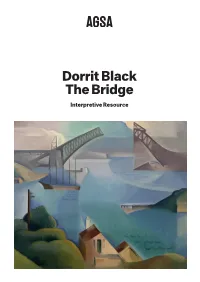

Dorrit Black the Bridge

Dorrit Black The Bridge Interpretive Resource Australian modernist Dorrit Black The Bridge, 1930 was Australia’s first Image (below) and image detail (cover) (1891–1951) was a painter and printmaker cubist landscape, and demonstrated a Dorrit Black, Australia, who completed her formal studies at the new approach to the painting of Sydney 1891–1951, The Bridge, 1930, Sydney, oil on South Australian School of Arts and Crafts Harbour. As the eye moves across the canvas on board, 60.0 x around 1914 and like many of her peers, picture plane, Black cleverly combines 81.0 cm; Bequest of the artist 1951, Art Gallery of travelled to Europe in 1927 to study the the passage of time in a single painting. South Australia, Adelaide. contemporary art scene. During her two The delicately fragmented composition years away her painting style matured as and sensitive colour reveals her French she absorbed ideas of the French cubist cubist teachings including Lhote’s dynamic painters André Lhote and Albert Gleizes. compositional methods and Gleizes’s vivid Black returned to Australia as a passionate colour palette. Having previously learnt to supporter of Cubism and made significant simplify form through her linocut studies contribution to the art community by in London with pioneer printmaker, Claude teaching, promoting and practising Flight, all of Black’s European influences modernism, initially in Sydney, and then in were combined in this modern response to Adelaide in the 1940s. the Australian landscape. Dorrit Black – The Bridge, 1930 Interpretive Resource agsa.sa.gov.au/education 2 Early Years Primary Responding Responding What shapes can you see in this painting? What new buildings have you seen built Which ones are repeated? in recent times? How was the process documented? Did any artists capture The Sydney Harbour Bridge is considered a this process? Consider buildings you see national icon – something we recognise as regularly, which buildings do you think Australian. -

Making Modernism Student Resource

STUDENT RESOURCE INTRODUCTION The time of Georgia O’Keeffe, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith was characterised by scientific discovery, war, rapid urbanisation, engineering and industrialisation. Rather than working toward tonal modelling and ‘imitative drawing’ techniques, these women artists were driven toward abstraction by theories about colour and distortion initiated by the Fauvists in Europe, as well as by their own fascination with the depiction of light. Arthur Wesley Dow’s design exercises — influenced by Japanese aesthetics (Orientalism) that aimed to achieve harmony using notan, or ‘dark and light’ — were being taught around the world, including to O’Keeffe at a Georgia O’Keeffe / Ram’s Head, Blue Morning Glory (detail) 1938 / Gift of The Burnett Foundation 2007 / University of Virginia summer school; here in Australia, Collection: Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe / © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Preston was reading about them. 1, 2 BEFORE VISIT ‘ Do not go where the path may RESEARCH – What is Modernism? Write a definition lead, go instead where there that considers the following terms: rapid change, is no path and leave a trail.’ world view, transportation, industrialisation, innovation, experimentation, rejecting tradition, realism, abstraction. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82), North American essayist and poet Locate on maps the cities, regions and other places significant to O’Keeffe, Preston and Cossington Smith, including New Mexico, Sydney Harbour and England. DEVELOP – Use Google Earth to find and take screen ‘ Lasting art is endlessly interesting shots of these locations and the vehicles in use at the time. because its meaning is constantly remade by each generation, by each REFLECT – Consider the impact of travel on artists, individual viewer.’ seeing new countries and landscapes for the first time. -

Australian Art

Australian Art Collectors’ List No. 166, 2013 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke Street) Kensington (Sydney) NSW Ph: (02) 9663 4848; Fax: (02) 9663 4447 Email: [email protected] Web: joseflebovicgallery.com JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY Established 1977 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney) NSW Post: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia Tel: (02) 9663 4848 • Fax: (02) 9663 4447 • Intl: (+61-2) Email: [email protected] • Web: joseflebovicgallery.com Open: Wed to Fri 1-6pm, Sat 12-5pm, or by appointment • ABN 15 800 737 094 Member of • Association of International Photography Art Dealers Inc. International Fine Print Dealers Assoc. • Australian Art & Antique Dealers Assoc. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 166, 2013 Australian Art 1. Ian Armstrong (Aust., 1923-2005). 2. Ian Armstrong (Aust., 1923-2005). [Nurse Writing], 1968. Etching and aqua- [Nurse With Medications], 1968. Etching On exhibition from Sat., 28 September to Sat., 9 November. tint, editioned 10/10, signed and dated in and aquatint, editioned 4/10, signed and All items will be illustrated on our website from 5 October. pencil in lower margin, 13.5 x 11.8cm. Glue dated in pencil in lower margin, 13.4 x stains to margins. 11.7cm. Glue stains to margins. Prices are in Australian dollars and include GST. Exch. rates as at $770 Armstrong’s images may have been inspired $770 time of printing: AUD $1.00 = USD $0.92¢; UK £0.59p by his stay in hospital due to a heart attack and © Licence by VISCOPY AUSTRALIA 2013 LRN 5523 subsequent surgery. Ref: Wiki. Compiled by Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Lenka Miklos, Mariela Brozky, Takeaki Totsuka Rex Dupain 3. -

Australian & International Photography

Australian & International Photography Collectors’ List No. 185, 2016 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW phone: (02) 9663 4848 email: [email protected] web: joseflebovicgallery.com JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY 19th Century Established 1977 1.| Robert Macpherson (Brit., 1811-1872).| Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) Arch Of Constantine, Rome, Italy, |c1850s.| Albumen paper photograph, numbered “2” in Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW pencil in “R. Macpherson, Rome” blind stamp Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia on backing below image, 31.3 x 40cm. Slight developing flaws and scuffing to image lower Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 centre and right, repaired minor tears to upper Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com edge, minor foxing or soiling, laid down on Open: Monday to Saturday from 1 to 6pm by chance or by appointment original backing.| $2,200| COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 185, 2016 Held in Canadian Centre for Architecture. 2.| Robert Macpherson (Brit., 1811-1872).| Australian & International The Castle And Bridge Of Saint Angelo, With The Vatican In The Distance, Vatican City,| Photography c1850s.| Albumen paper photograph, num- On exhibition from Sat., 3 December to Sat., 11 February. bered “34” in pencil in “R. Macpherson, Rome” blind stamp on backing below image, 24.4 x All items will be illustrated on our website from 17 December. 37.4cm. Slight fading and foxing to image, laid Prices are in Australian dollars, including GST. Exch. rates at down on original backing.| the time of printing: AUD $1.00 = USD $0.76¢; UK£0.60p $1,650| Held in Canadian Centre for Architecture.