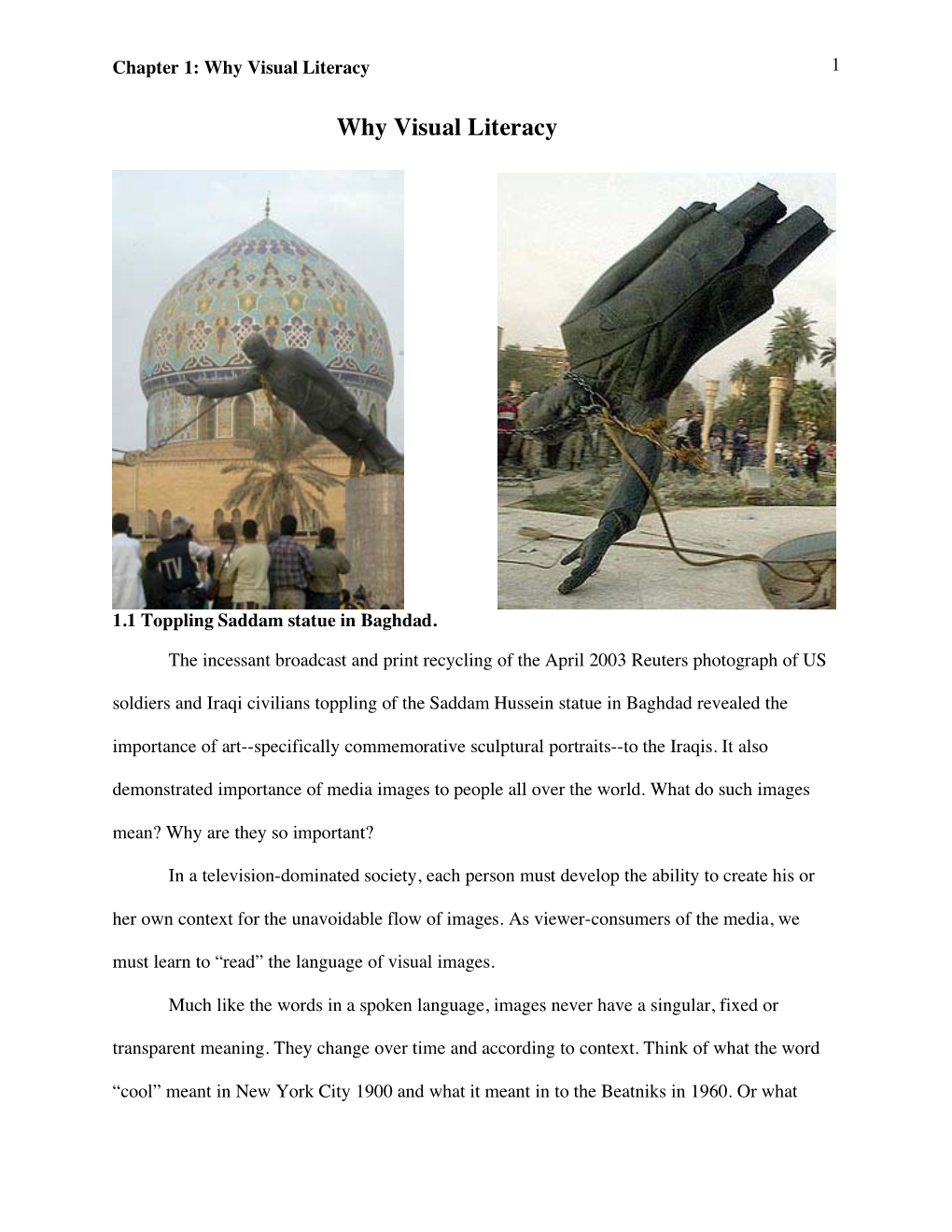

Chapter 1: Why Visual Literacy 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

Solar System Genealogy Revealed by Meteorites

Press release – August 27th 2012 Solar System genealogy revealed by meteorites The stellar environment of our Solar System at its birth is poorly known, as it has accomplished some twenty revolutions around the Galactic centre since its formation 4.5 billion years ago. Matthieu Gounelle from the Laboratoire de Minéralogie et Cosmochimie du Muséum (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle/CNRS) and Georges Meynet from the Observatoire de Genève established the Solar System genealogy in elucidating the origin of a radioactive element, 26Al, which was present in the nascent Solar System. Their results are published this week in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. Aluminium-26, a radioactive isotope of aluminium with a mean life of one million years was present in some meteoritic inclusions during the very first stages of the Solar System, 4.5 billion years ago. Its presence in the nascent Solar System had long been attributed to a supernova1 which would have exploded nearby the forming Solar System. However, the rarity of the association of a supernova and a forming star would imply that very special conditions lead to the Solar System formation. From astronomical observations of young stars and astrophysical modelling, the two authors showed that the 26Al originated instead from the wind of a massive star born a few million years before the Solar System. This star, not only synthesized the 26Al found in meteoritic inclusions but also lead to the formation of the Solar System in accumulating gigantic quantities of hydrogen gas, from which a new star generation (including our Sun) formed. This massive star can therefore be considered as the parent star of our Solar System. -

A High Contrast Survey for Extrasolar Giant Planets with the Simultaneous Differential Imager (SDI)

A High Contrast Survey for Extrasolar Giant Planets with the Simultaneous Differential Imager (SDI) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Biller, Beth Alison Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:58:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194542 A HIGH CONTRAST SURVEY FOR EXTRASOLAR GIANT PLANETS WITH THE SIMULTANEOUS DIFFERENTIAL IMAGER (SDI) by Beth Alison Biller A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ASTRONOMY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 7 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dis- sertation prepared by Beth Alison Biller entitled “A High Contrast Survey for Extrasolar Giant Planets with the Simultaneous Differential Imager (SDI)” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: June 29, 2007 Laird Close Date: June 29, 2007 Don McCarthy Date: June 29, 2007 John Bieging Date: June 29, 2007 Glenn Schneider Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candi- date's submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Formation of the Solar System

The formation of the solar system S Pfalzner1, M B Davies2, M Gounelle3;4, A Johansen2,CMunker¨ 5, P Lacerda6, S Portegies Zwart7, L Testi8;9, M Trieloff10 & D Veras11 1 Max-Planck Institut fur¨ Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hugel¨ 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Lund Observatory, Department of Astronomy and Theoretical Physics, Box 43, 22100 Lund, Sweden 3 IMPMC, Museum´ National d’Histoire Naturelle, Sorbonne Universites,´ CNRS, UPMC & IRD, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4 Institut Universitaire de France, 103 boulevard Saint-Michel, 75005 Paris, France 5 Institut fur¨ Geologie und Mineralogie, Universitat¨ zu Koln,¨ Zulpicherstr.¨ 49b 50674 Koln,¨ Germany 6 Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Sonnensystemforschung, Justus-von-Liebig-Weg 3, 37077 Gottingen,¨ Germany 7 Leiden University, Sterrewacht Leiden, PO-Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands 8 ESO, Karl Schwarzschild str. 2, D-85748 Garching, Germany 9 INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, I-50125, Firenze, Italy 10 Institut fur¨ Geowissenschaften, Im Neuenheimer Feld 234-236, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 11 Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] November 2014 Abstract. The solar system started to form about 4.56 Gyr ago and despite the long intervening time span, there still exist several clues about its formation. The three major sources for this information are meteorites, the present solar system structure and the planet- forming systems around young stars. In this introduction we give an overview of the current understanding of the solar system formation from all these different research fields. This includes the question of the lifetime of the solar protoplanetary disc, the different stages of planet formation, their duration, and their relative importance. -

Location and Orientation of Teotihuacan, Mexico: Water Worship and Processional Space

Location and Orientation of Teotihuacan, Mexico: Water Worship and Processional Space Susan Toby Evans “Processions and pilgrimages produced a continuous movement that animated the landscape, thus we are dealing with fundamental ritual processes that created the sacred landscape.” Johanna Broda, this volume Introduction: The Cultural Ecology of Teotihuacan’s Placement In this paper, the ritual practice of Teotihuacan Valley, as well as with the city’s procession is argued to have provided an cosmological setting. The grid’s orientation impetus for the location and orientation of the addressed practical problems such as grading ancient city of Teotihuacan within its and drainage while it maximized ardent efforts environmental context, the Teotihuacan Valley. by worshippers to connect with the living world Cultural ecology and ethnohistory will they revered: the same urban plan that illuminate the rich corpus of information about channeled psychic energy toward sacred the city’s development and the valley’s elements of the environment also channeled geographical features, and suggest that the city’s water and waste through the city and onto topographical situation was generated by its agricultural fields. regional landscape and the needs of its planners Supporting the idea that the city’s to urbanize the site while supporting a growing orientation and location were deliberate population, which involved increasing adaptations to the Teotihuacan Valley, and that agricultural productivity and intensifying the processions were a vital component of propitiation of fertility deities. Teotihuacanos calculations to insure continued fertility, maximized crop production in their valley’s evidence is drawn from: different growing zones, while gridding their the Teotihuacan Valley’s natural city with processional avenues and arenas. -

THE CAPITAL of ELSEWHERE: PLACES, FICTIONS, HOUSTONS a Dissertation by CLIFFORD WALLACE HUDDER Submitted to the Office of Gradua

THE CAPITAL OF ELSEWHERE: PLACES, FICTIONS, HOUSTONS A Dissertation by CLIFFORD WALLACE HUDDER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, David McWhirter Committee Members, Juan Alonzo Emily Johansen Jonathan Smith Head of Department, Maura Ives May 2018 Major Subject: English Copyright 2018 Clifford Wallace Hudder ABSTRACT This study examines the manner in which fictional works illuminate the complex identity of place by investigating authors associated with a single American city, Houston, Texas, focusing chapter length studies on four: Donald Barthelme, Rick Bass, Farnoosh Moshiri, and Tony Diaz. Its methodological framework is the “geocritical” approach, wherein, as stated by Bertrand Westphal, “[t]he study of the viewpoint of an author or of a series of authors . will be superseded in favor of examining a multiplicity of heterogeneous points of view, which all converge in a given place, the primum mobile of the analysis.” This multifocal approach reveals Houston as a place of unusual juxtapositions formed by freeway culture, fluidity of categories due to a lack of zoning regulations, a “timelessness” resulting from constant bulldozing of the past, and a powerful concern for market forces owing to a laissez-faire attitude towards business and regulation, brought together in what architect Peter Rowe labels the city’s “ever-present and unvarnished capacity for destabilization and shape-shifting.” Variations of the place-experience of Houston based on the four authors’ heterogeneous viewpoints are examined, and potential drawbacks of the geocritical model in identifying the nature of place through the lens of literature are explored. -

The Abundance of 26Al-Rich Planetary Systems in the Galaxy Matthieu Gounelle1,2

A&A 582, A26 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526174 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics The abundance of 26Al-rich planetary systems in the Galaxy Matthieu Gounelle1;2 1 IMPMC, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Sorbonne Universités, CNRS, UPMC & IRD, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut Universitaire de France, 103 boulevard Saint-Michel, 75005 Paris, France Received 24 March 2015 / Accepted 17 June 2015 ABSTRACT One of the most puzzling properties of the solar system is the high abundance at its birth of 26Al, a short-lived radionuclide with a mean life of 1 Myr. Now decayed, it has left its imprint in primitive meteoritic solids. The origin of 26Al in the early solar system has been debated for decades and strongly constrains the astrophysical context of the Sun and planets formation. We show that, according to the present understanding of star-formation mechanisms, it is very unlikely that a nearby supernova has delivered 26Al into the nascent solar system. A more promising model is the one whereby the Sun formed in a wind-enriched, 26Al-rich dense shell surrounding a massive star (M > 32 M ). We calculate that the probability of any given star in the Galaxy being born in such a setting, corresponding to a well-known mode of star formation, is of the order of 1%. It means that our solar system, though not the rule, is relatively common and that many exo-planetary systems in the Galaxy might exhibit comparable enrichments in 26Al. Such enrichments played an important role in the early evolution of planets because 26Al is the main heat source for planetary embryos. -

Remembering Coyolxauhqui As a Birthing Text

UCLA Regeneración Tlacuilolli: UCLA Raza Studies Journal Title Remembering Coyolxauhqui as a Birthing Text Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2dt752tn Journal Regeneración Tlacuilolli: UCLA Raza Studies Journal, 2(1) ISSN 2371-9575 Authors Luna, Jennie Galeana, Martha Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Essays Luna and Galeana Remembering Coyolxauhqui as a Birthing Text Jennie Luna and Martha Galeana Image 1: Coyolxauhqui from Anzures (1991) Abstract: This article examines several interpretations of the stone image of Coyolxauhqui: 1) the Early Academic interpretation established by anthropolo- gists; 2) the Xicana Feminist interpretation; and 3) a Partera/Midwife perspective which re-envisions Coyolxauhqui as a birthing diagram or guide for women in labor. Historically, Coyolxauhqui has been referred to as the “dis-membered woman” and used as evidence of the victimization of women in Mesoameri- can society. This article challenges the conventional notions of Coyolxauhqui and argues that even the reformist understandings rendered by Xicana feminist thinkers were still founded from and built upon colonial interpretations of this image. By re-envisioning and re-membering Coyolxauhqui through a Partera/ midwifery lens, a new interpretation emerges. Rather than being regarded as the “dis-membered woman” Coyolxauhqui is revered through an Indigenous women’s perspective that honors her as a text about the life-giving force of women. Key words: Coyolxauhqui, Mexica, moon cycle, midwifery, partera, Indig- enous women, Xicana, traditional birthing practices, uterus, Xicana feminism, empowerment © 2016 Jennie Luna and Martha Galeana. All Rights Reserved. 7 Luna and Galeana Introduction Since 1978, when the stone image of Coyolxauhqui was excavated during the construction of México City’s underground public trans- portation system, multiple interpretations have continued to emerge with sometimes conflicting meanings and analysis. -

SACRED SPACES and RITUALS: AZTEC ART and ARCHITECTURE: FOCUS (Tenochtitlán)

SACRED SPACES and RITUALS: AZTEC ART and ARCHITECTURE: FOCUS (Tenochtitlán) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://www.sacred- destinations.com/mexic o/mexico-city-templo- mayor TITLE or DESIGNATION: Templo Mayor CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Mexica (Aztec) DATE: c. 1500 C.E. LOCATION: Tenochtitlán (present- day Mexico City) TITLE or DESIGNATION: Aztec Calendar Stone CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Mexica (Aztec) DATE: c. 1500 C.E. MEDIUM: basalt TITLE or DESIGNATION: Coatlicue from Tenochtitlán CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Mexica (Aztec) DATE: c. 1487-1520 C.E. MEDIUM: volcanic stone ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy. org/humanities/art-africa- oceania- americas/mesoamerica/azte c-mexica/a/mexica-templo- mayor-at-tenochtitlan-the- coyolxauhqui-stone-and-an- olmec-style-mask TITLE or DESIGNATION: Coyolxauhqui (She of the Bells) CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Mexica (Aztec) DATE: late 15th century C.E. MEDIUM: volcanic stone ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacade my.org/humanities/art- africa-oceania- americas/mesoamerica/o lmec/v/olmec-mask TITLE or DESIGNATION: Olmec-style mask from Tenochtitlán CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Mexica (Aztec) DATE: c. 1200-400 B.C.E.; buried c. 1470 C.E. MEDIUM: jadeite SACRED SPACES and RITUALS: AZTEC ART and ARCHITECTURE: SELECTED TEXT (Tenochtitlán) Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlán, c. 1500 According to Aztec sources, Templo Mayor was built on this spot because an eagle was seen perched on a cactus devouring a snake, in fulfillment of a prophecy. Construction on the temple began sometime after 1325 and was enlarged over the next two centuries. At the time of the 1521 Spanish Conquest, the site was the center of religious life for the city of 300,000. -

What Size Is the Universe? the Cosmic Uroboros

Chapter 6 What Size is the Universe? The Cosmic Uroboros The size of a human being is at the center of all the possible sizes in the universe. This amazing assertion challenges not only the centuries-old philosophical assumption that humans are insignificantly small compared to the vastness of the universe but also the logical assumption that there is no such thing as a central size. Both assumptions are false, but we have to reconsider the key words of the assertion – center, possible, size, and universe – to reveal the prejudices built into them that constrict and distort our picture of reality. In the modern universe there is a largest and a smallest size, and therefore a middle size. The size of a thing is not arbitrary but crucial to its nature, which is why scale models can never really work. Only by understanding size and its role in determining which laws of physics matter on different size scales can we can get an accurate perspective on anything outside the narrow realm of human experience. This chapter will develop a new symbolic picture of the universe that portrays us in our true place among everything else that exists. There are wildly different-sized objects in the universe. Betelgeuse is the bright star at the upper left corner of the familiar winter constellation Orion. It is a red giant so monstrously larger than our sun that it could fill the orbit of Mars. Earth is a mere pebble beside it. But compared to our home Galaxy, the Milky Way, Betelgeuse is just a spark in a raging forest fire. -

Borderlands / La Frontera: the New Mestiza

traducción de '¿ A p ifá h S u m g BORDERLANDS M i ■ft*"* LA FRONTERA GLORIA ANZALDÚA 4 m / # BORDERLANDS LA fRONTERA GLORIA ANZALDUA Introducción de SONIA SALDIVAR Traducción de CARMEN VALLE colección ENSAYO Título original: Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza © Del libro: Gloria Anzaldúa © De la traducción: Carmen Valle © De esta edición: Capitán Swing Libros, S. L. c/ Rafael Finat 58, 2o 4 - 28044 Madrid Tlf: (+34) 630 022 531 [email protected] www.capltanswing.com © Diseño gráfico: Filo Estudio - www.filoestudio.com Corrección ortotipográfica: Victoria Parra Ortiz ISBN: 978-84-945043-2-7 Depósito Legal: M-6863-2016 Código BIC: FV Impreso en España / Printed in Spain Artes Gráficas Cofás (Móstoles) Madrid Queda prohibida, sin autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright, bajo las sanciones establecidas en las leyes, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento. ÍNDICE Reconocimientos.....................................................................................................................................9 Introducción a la segunda edición, por Sonia Saldivar Hull ...................................... 11 Traducir Borderlands. La Frontera, por Carmen Valle Simón.....................................29 Prefacio a la primera edición, por Gloria Anzaldúa.......................................................35 Atravesando fronteras / Crossing borders 01. La patria, Aztlán .................................................................................................................... -

A Global Survey and Regional Scale Study of Coronae on Venus

A Global Survey and Regional Scale Study of Coronae on Venus A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London By Simon W. Tapper Department of Geological Sciences University College London 1998 ProQuest Number: U643667 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643667 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Coronae are large-scale geological structures on Venus normally consisting of a planimetrically circular topographic rim which encircles a basin. They are considered to have formed by plume activity. The thesis describes and examines the characteristics of coronae using a new and comprehensive database which is used to further understanding of corona properties and the geological evolution of Venus. Topographic data were surveyed to identify coronae which are not easily detectable in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images because they lack the annulus of brittle scale fractures that were previously considered to characterise all coronae. Data used to describe the distribution, morphology, geological setting and associated volcanic and tectonic structures were obtained from altimetry, high resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) images returned by the 1990 Magellan mission and synthetic stereo images generated from Magellan data.