Queer Feminist Thought from Lebanon Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of Arab Women Report Access to Justice for Women And

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia Status of Arab Women Report Access to Justice for Women and Girls in the Arab Region: From Ratification to Implementation of International Instruments E/ESCWA/ECW/2015/1 Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia Status of Arab Women Report Access to Justice for Women and Girls in the Arab Region: From Ratification to Implementation of International Instruments UNITED NATIONS Beirut © 2014 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA). All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: ESCWA, United Nations House, Riad El Solh Square, P.O. Box: 11-8575, Beirut, Lebanon. E-mail: [email protected]; website: www.escwa.un.org United Nations’ publication issued by ESCWA. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of commercial names and products does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. Symbols of the United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. 15-00071 3 Acknowledgements This publication was prepared at the ESCWA Centre for Women (ECW) by Ms. Lana Baydas, First Social Affairs Officer, under the substantive guidance and overall supervision of Ms. -

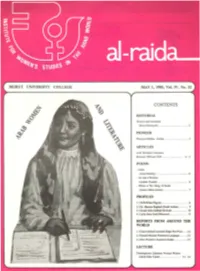

Al- Raida Issue

BEIRUT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE MAY 1, 1985, Vol. IV, No. 32 CONTENTS EDITORIAL Women and Literature (Rose Ghurayyib) ... ............................. 2 PIONEER Thorayya Malhas - Jordan - ......................... 3 ARTICLES Arab Feminine Literature Between 1980 and 1950 ................... .. 4 - 5 POEMS - Liban (Amal Saleeby) .................... ... .. ....." .... 6 - Un mal d'Enfance (Andree Chedid) ............................ ..... 6 - Where is Thy Sting, 0 Death (Lamia Abbas Amara) . .... ....... ....... 7 PROFILES I ) Alifa Rifaat (Egypt).... ...... .. .. ........... .. .. 8 2 ) Dr. Mariam Bagdadi (Saudi Arabia) .. ........ 9 3 ) Souad Abou Sabbah (Kuwait) ................ 10 4 ) Leila Abou Zeid (Morocco) ................... 11 REPORTS FROM AROUND THE WORLD I ) Claire Gel>eyli awarded Edgar Poe Prize ....• 12 2 ) French Minister Feminizes Language ........ 12 ,3 ) New Women's Journal in Sudan ............. 12 LECTURE Contemporary Lebanese Women Writers (;-./aiik Saba Yared) ....................... \3 - 16 ( Editorial ) Women and Literature The «gift of the tongue» has been generally them a unique means for claiming their rights and acknowledged as one of women's chief aptitudes. In expounding their demands and their needs. Literary world mythology and history, women performed several production has the possibility of travelling, of spreading roles requiring eloquence and fluency: those ofpriestess, far and wide and reaching every corner of the world. prophetess, mourner, poetess, sorceress, soothsayer, Through literature women are able to emerge as a world singer, mourner and story-teller (for ex. Scheherazade). power, as a «global sisterhood». In this respect, they may We read that Maysoun, wife of the first Omayyad Caliph, strive for improvement and reform in every field and Mu'awia, longed to return to her Bedouin tent in the claim the instauration of justice and the elimination of desert, which she preferred to the sumptuous Damascene exploitation not only in their own spheres but also in those Palace. -

Brazen (Spring 2011) Hollins University

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Brazen - Gender & Women's Studies Department Gender & Women’s Studies Newsletters Spring 2011 Brazen (Spring 2011) Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/brazen Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brazen: Newsletter of the Gender & Women's Studes Department. Roanoke, Virginia, Hollins University. Spring 2011. This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Gender & Women’s Studies at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brazen - Gender & Women's Studies Department Newsletters by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. February 21, 2011 Volume IV, Issue 2 bra.zen Contemporary Metaphorical Representations of Arab Femininity by Emily Campbell, ‘12 Note: The following poems were inspired by and informed by various writings and artwork created by contemporary Arab women. Excès du Oiseau Fruit Unafraid femininity, and more- Fall, take the bruises but You can be shapeless, over, I found that these keep them beneath your can flow with the cur- pieces were in dialogue skin—be modest, hued rent, can hide behind with one another Inside this issue: in black and white things less dangerous regarding the same thematic conflicts; these rather than the blues than yourself—things Starting Smart at 2 I identify as and greens of peacocks. which would map you, Hollins Clean yourself, sweep confine you—but you confinement versus the soil from your cage; are a pomegranate, a movement, suppression On Being a Dance Artist 3 you cannot grow any- thing of flesh and color versus subversion, and thing in there (and what and wetness. -

Rural Women Cooperatives Challenge Patriarchal Market Institutions in Lebanon

CASE STUDIES IN WOMEN’S ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT A case from the Middle East: What’s in a day’s work? Rural women cooperatives challenge patriarchal market institutions in Lebanon 1 Edited by Lina Abu Habib from CRTDA Prelude This case study focuses on rural women’s cooperatives in Lebanon and the gender-based discrimination they face in accessing markets. The case study begins by setting the overall economic and gender equality context before focusing on specific issues related to rural women’s cooperatives and the strategies devised to break gender and other barriers to accessing local markets. Country fact sheet HDI: Lebanon ranks 80th in the 2004 Human Development Report (177 countries). 1 http://www.crtda.org 1 GDI (Gender-related Development Index) rank: 64 (144 countries). In 2002, Lebanon’s total population was 3.6 million, of which 87.2 per cent lived in urban areas; almost one-third (29.6 per cent) were under 15 years of age; 35 per cent of the population lived in poor conditions and 6.3 per cent lived on less than USD 1.3 a day. The annual population growth rate between 1975 and 2002 was 1 per cent. Adult literacy rate (2002): female 81.06 per cent, male 92.4 per cent. The total labour force of the country is estimated at 34 per cent of the total population. The labour market in Lebanon has an imbalanced composition; it is estimated that women constitute only 21.7 per cent of the labour force. The annual GDP growth rate per capita was 3.1 per cent between 1990 and 2002. -

Women's Needs and Gender Equality in Lebanon's COVID-19

IN FOCUS March 23, 2020 WOMEN’S NEEDS AND GENDER EQUALITY IN LEBANON’S COVID-19 RESPONSE Photo © UN Women/Ryan Brown Based on lessons learned from other epidemics, namely Ebola and Zika virus, this paper outlines gender issues related to the COVID-19 outbreak and response in Lebanon. Women and girls’ immediate and long-term needs must be addressed and integrated into Lebanon’s response, in order to both ensure women’s access to services and human rights, and to enable women to equally continue to contribute to shaping the response. Recommended guidelines for both immediate and longer-term action are proposed for COVID-19 stakeholders in Lebanon. Global COVID-19 Response On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared the corona virus (COVID-19) a global pandemic. Originating in Wuhan province of central China in late 2019, the corona virus has since spread to 166 countries to date. With the first case detected in Lebanon on February 19th, COVID-19 poses significant risks for the country. COVID-19 reaches Lebanon at a time of historic and devastating economic crisis, rising unemployment, the application of informal capital controls which have stemmed imports (including critical health imports) and a weak social protection system. The potential short and longer- term consequences of this for Lebanon are exacerbated by issues of urban overcrowding, both within formal and informal refugee camps and settlements, and across the country more broadly. Pandemics magnifyy all existing inequalities; class, ability, age and gender. Purely as a physical illness, the data to date suggests that COVID-19 appears to affect women less severely. -

The Making of a Leftist Milieu: Anti-Colonialism, Anti-Fascism, and the Political Engagement of Intellectuals in Mandate Lebanon, 1920- 1948

THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2017 1 THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2017 2 This dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of an invisible generation of leftists that were active in Lebanon, and more generally in the Levant, between the years 1920 and 1948. It chronicles the foundation and development of this intellectual milieu within the political Left, and how intellectuals interpreted leftist principles and struggled to maintain a fluid, ideologically non-rigid space, in which they incorporated an array of ideas and affinities, and formulated their own distinct worldviews. More broadly, this study is concerned with how intellectuals in the post-World War One period engaged with the political sphere and negotiated their presence within new structures of power. It explains the social, political, as well as personal contexts that prompted intellectuals embrace certain ideas. Using periodicals, personal papers, memoirs, and collections of primary material produced by this milieu, this dissertation argues that leftist intellectuals pushed to politicize the role and figure of the ‘intellectual’. -

Psychological Study of Sex & Gender

Updated last on October 9, 2020 Psychological Study of Sex & Gender PSY 2240 [4-credits] Fall 2020 Özge Savaş (she/her) || [email protected] || Barn 214A Class meets online Every Monday and Thursday, 2-4:30pm Student (office) hours online Every Wednesday, 1:30-3:30pm (and by appointment) COURSE DESCRIPTION & OBJECTIVES Why is the first thing people want to know about a baby is their gender/sex? How are children socialized into gender/sex binaries? How do dominant social and cultural formations actually produce men and women? How is gender/sex related to sexuality? What is it that we are attracted to in another person? Body frames? Masculinity/femininity? Having a penis or a vagina/vulva? How does gender/sex depend on other categories such as race/ethnicity, nationality, class, religion, and ability? How do interlocking systems of oppression (e.g. sexism, racism, classism, xenophobia, ableism) influence people’s lives? In this class, we will learn to make evidence-based arguments about gender and sex while situating lived experiences of women and sexual minorities in context, gain media literacy in examining examples from pop culture, understand the role of heteropatriarchal and racist ideologies and institutions in social inequity, and learn to think and write critically about gender in its social, cultural, historical and political context. LEARNING GOALS § Explain how dominant social and cultural formations of gender actually produce women and men, girls and boys. § Identify interlocking systems of oppression (i.e. heteropatriarchy, transphobia, racism, classism, xenophobia, ableism) and analyze the relationship of gender other categories (i.e. race, ethnicity, nationality, ability, class, sexuality). -

Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy Rethinking Women of Color Organizing

Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy Rethinking Women of Color Organizing Andrea Smith Scenario #1 A group of women of color come together to organize. An argu- ment ensues about whether or not Arab women should be included. Some argue that Arab women are "white" since they have been classified as such in the US census. Another argument erupts over whether or not Latinas qualify as "women of color," since some may be classified as "white" in their Latin American countries of origin and/or "pass" as white in the United States. Scenario #2 In a discussion on racism, some people argue that Native peoples suffer from less racism than other people of color because they gen- erally do not reside in segregated neighborhoods within the United States. In addition, some argue that since tribes now have gaming, Native peoples are no longer "oppressed." Scenario #3 A multiracial campaign develops involving diverse conpunities of color in which some participants charge that we must stop the blacklwhite binary, and end Black hegemony over people of color politics to develop a more "multicultural" framework. However, this campaign continues to rely on strategies and cultural motifs developed by the Black Civil Rights struggle in the United States. These incidents, which happen quite frequently in "women of color" or "pee;' of color" political organizing struggles, are often explained as a consequenii. "oppression olympics." That is to say, one problem we have is that we are too b::- fighting over who is more oppressed. In this essay, I want to argue that thescir- dents are not so much the result of "oppression olympics" but are more abour t-, we have inadequately framed "women of color" or "people of color" politics. -

Lebanese and Syrians in Egypt

Lebanese and Syrians in Egypt ALBERT HOURANI The land which lies to the east of Egypt, across the Sinai Peninsula, was known to previous generations of European travellers and writers as ‘Syria’, and to Egyptians as Barr al-Sham. When those who had been born there emigrated, they usually referred to themselves as ‘Syrians’. This chapter will deal with all of them, whether or not they came from the land which is now the Lebanese Republic, and whether they called themselves Syrians or Lebanese. Syria (in this broader sense) and Egypt lie so close to each other that the movement of people between them has been continuous, although for the most part it has gone from Syria to Egypt rather than in the opposite direction. It has been unlike the movements which are the subject of other chapters in this book, in that it has been, at least for the last millennium or so, a movement within the same world of language, belief and culture. Merchants carried the products of Syria by land across the Sinai peninsula or by sea from the Syrian ports to the Mediterranean ports of Egypt, and students went to study at the great centre of Islamic learning, the Azhar mosque in Cairo. The movement must have increased when the two countries were incorporated in the same empire and therefore the same trading area, as they were during the period of Ayyubid and Mamluk rule from the twelfth to the fifteenth century, and later during that of the Ottomans. Many of those who went from Syria to Egypt remained there. -

The Iconic News Image As Visual Event in Photojournalism and Digital Media

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i The Iconic News Image as Visual Event in Photojournalism and Digital Media A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Media Studies At Massey University, Manawatu New Zealand Samantha Diane Kelly 2013 ii Abstract This thesis shows how the uses and meanings of the iconic news image have changed with the emergence of digital media. Most of the iconic photographs of the twentieth century were produced by photojournalists and published in mass circulation newspapers and magazines. In the twenty–first century, amateurs have greater access to image producing technologies and greater capacity to disseminate their images through the Internet. This situation has made possible the use of iconic news images to support political agendas other than those promoted in the media institutions and beyond the range of censorship imposed by those media. In order to demonstrate the functions and understand this unprecedented situation, this thesis explores how iconic news images produce meaning. I consider formal definitions of iconic news images but adopt Nicholas Mirzoeff's theory of the visual event to explain how the meanings of iconic news images are impacted by historical context, media institutions and viewer responses. This dynamic model of visual communication allows us to see that iconic news images indeed function as events and that there is a political struggle over the creation, staging, publication and interpretation of those events. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Silence the Shame at American Sushi Recording Studio

The Silence the Shame movement launched in 2016, and Nick Cannon became the rst Artist/ Entertainer to endorse Silence the Shame (STS) for our viral In 2017/2018, Silence the Shame launched campaign. social media campaigns that garnered more than 90 million impressions and received online support from musicians and inuencers across the country. Silence the Shame at American Sushi Recording Studio In July 2017, American Sushi Recording Studio and The Black Media hosted an intimate mental health discussion in their Little 5 Points Studio in Atlanta, Georgia. The room was full of music creatives that appreciated Shanti's unique point of view. & In June 2017, Founder Shanti Das joined Singer Lalah Hathaway, Rapper Vic Mensa, Singer Charlie Wilson, and Dr. Reef Karim for a panel discussion called The Health of Hip-Hop and R&B moderated by Justin Hunte. The event took placed in Los Angeles at The Grammy Museum. That marked the beginning of our relationship with MusiCares. In partnership with the Grammy’s Foundation, MusiCares, panel discussion were curated for creatives and executives in the music industry that enabled a safe space to discuss mental health and wellness in the music industry. The rst panel, Soundtrack of Mental Health, occurred in May 2018 in Atlanta and was In 2019 STS kicked o Mental Health Awareness live-streamed via Rolling Out. The panelists Month (May) in New York City with The included Founder Shanti Das, Rapper David Soundtrack of Mental Health Vol. 2 at Island Banner, Producer Bryan Michael Cox, Vaughn Gay Records. Panelists included Founder Shanti Das, (Licensed Counselor), Music Exec David Lighty, Media Mogul Charlamagne the God, Manager and Renowned Vocal Coach Mama Jan Smith.