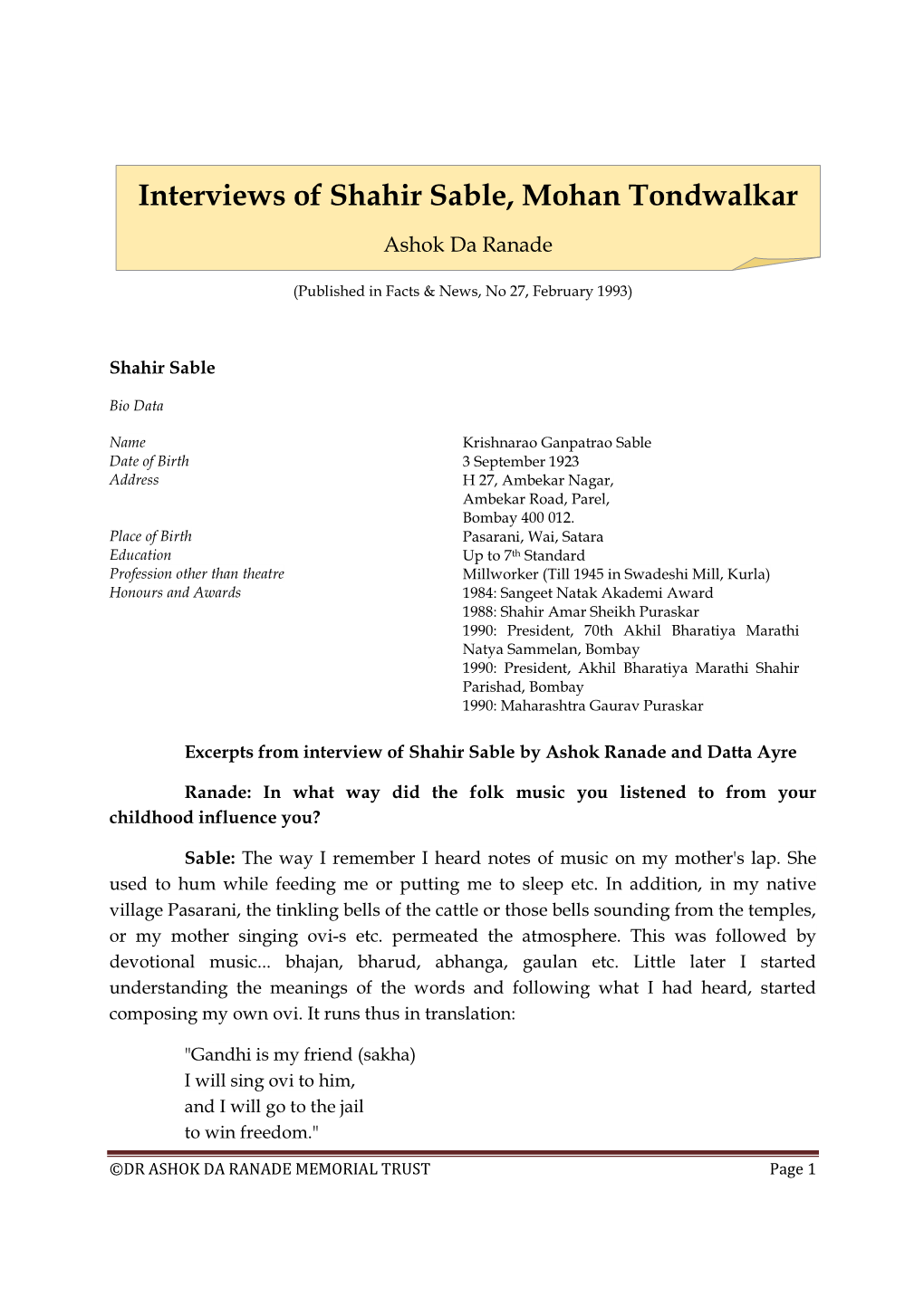

Interviews of Shahir Sable, Mohan Tondwalkar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 1, Issue 1 I May 2015 ISSN : 2395 - 4817

The Global Journal of Literary Studies | Volume 1, Issue 1 I May 2015 ISSN : 2395 - 4817 The Global Journal of Literary Studies I May 2015 I Vol. 1, Issue 1 I ISSN : 2395 4817 EXECUTIVE BOARD OF EDITORS Dr. Mitul Trivedi Prof. Piyush Joshi President H M Patel Institute of English Training and Research, Gujarat, The Global Association of English Studies INDIA. Dr. Paula Greathouse Prof. Shefali Bakshi Prof. Karen Andresa Dr M Saravanapava Iyer Tennessee Technological Amity University, Lucknow Santorum University of Jaffna Univesity, Tennessee, UNITED Campus, University de Santa Cruz do Sul Jaffna, SRI LANKA STATES OF AMERICA Uttar Pradesh, INDIA Rio Grande do Sul, BRAZIL Dr. Rajendrasinh Jadeja Prof. Sulabha Natraj Dr. Julie Ciancio Former Director, Prof. Ivana Grabar Professor and Head, Waymade California State University, H M Patel Institute of English University North, College of Education, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Training and Research Varaždin, CROATIA Gujarat, INDIA Gujarat, INDIA Dr. Momtazur Rahman Dr. Bahram Moghaddas Prof. Amrendra K. Sharma International University of Dr. Ipshita Hajra Sasmal Khazar Institute of Higher Dhofar University Business Agriculture and University of Hyderabad Education, Salalah, Technology, Dhaka, Hyderabad, INDIA. Mazandaran, IRAN. SULTANATE OF OMAN BANGLADESH Prof. Ashok Sachdeva Prof. Buroshiva Dasgupta Prof. Syed Md Golam Faruk Devi Ahilya University West Bengal University of Technology, West King Khalid University Indore, INDIA Bengal, INDIA Assir, SAUDI ARABIA The Global Journal of Literary Studies | Volume 1, Issue 1 I May 2015 ISSN : 2395 - 4817 The Global Journal of Literary Studies I May 2015 I Vol. 1, Issue 1 I ISSN : 2395 4817 Contents... Negotiating with Diaspora: Some Female Characters in Jhumpa Lahiri’s Unaccustomed Earth 01 Mafruha Ferdous, Assistant Professor, Department of English, Northern University, BANGLADESH. -

Inaugural Function Date: 17 December 2016 Time: 7:00 Pm Venue – Swatantrata Bhawan, BHU

Annexure - 1 RaashtriyaSanskritiMahotsav, Varanasi Inaugural Function Date: 17 December 2016 Time: 7:00 pm Venue – Swatantrata Bhawan, BHU Inauguration by Shri Mahesh Sharma, Honorable Minister of State- Ministry of Tourism & Culture (Independent Charge), Government of India Programme: 1) Indian Folk Music & Dance performances 2) Indian classical vocal by Padmavibhushan Smt. Girija Devi 3) Special attraction – Mallkhamb, Bajigars of Punjab, Martial arts of Kerala, North-East and Punjab, Been Jogi &Nagada from Haryana, KachhiGhodi&Bahrupiya of Rajsthan, Panchvadyam of Kerala. 4) Tat-Tvam-Asi -ArtExhibition on SimhasthKumbh. 5) Display of ‘ShirshPratishirsh’ Exhibition of Masks. 6) Display of Art Book’s Exhibition. 7) Display and Demonstration of Portrait Rangoli of Maharashtra. Annexure - 2 Raashtriya Sanskriti Mahotsav, Varanasi National Theatre Festival Date: 18 – 24 December, 2016 Time: 4:00 pm to 6:00 pm daily Venue: Swatantrata Bhawan, BHU, Varanasi Sl. Date Name of the Play and Direction 1. 18.12.2016 Name of the play: Andhayug Direction: Sumit Srivastava (Varanasi) 2. 19.12.2016 Name of the play: Vivekanand Direction: Shekhar Sen (New Delhi) 3. 20.12.2016 Name of the play: Rashmi Rathi Direction: Shant Srivastava (Gorakhpur) 4. 21.12.2016 Name of the play: Mohe Piya Direction: Waman Kendre (Mumbai) 5. 22.12.2016 Name of the play: Chanakya Direction: Manoj Joshi (Mumbai)Time: 11:30 am (Morning) 6. 23.12.2016 Name of the play: Raju Raja Ram Direction: Sharman Joshi (Mumbai) 7. 24.12.2016 Name of the play: Chakrvyuh Direction: Nitish Bharadwaj (Mumbai) Annexure-3 RASTRIYA SANSKRITI MAHOTSAV , VARANASI National Folk Music & Dance Festival 18.12.2016 – SwatantrataBhavan Sl. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Vasant Bapat - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Vasant Bapat - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Vasant Bapat(25 July 1922 – 17 September 2002) Vasant Vaman Bapat (Devanagari: ???? ???? ????) was a Marathi poet from Maharashtra, India. He was born on July 25, 1922 in Karad in Satara district of Maharashtra. <b>Education and Teaching Career</b> Bapat received a master's degree in Marathi and Sanskrit literature from S. P. College in Pune in 1948. He then taught Sanskrit and Marathi until 1976, first, National College and then Ruia College, both in Mumbai. During 1974-1982, he served as the Rabindranath Tagore Chair at Mumbai University. <b>Literary Career</b> Bapat published 30 collections of his poems. The following is a partial list of them: Bijalee (1952) Akaravi Disha (1962) Sakina (1972) Manasi (1977) Shatataraka Shinga Phunkale Rani Shoor Mardacha Powada Tejasi Rajasi Prawasachya Kawita Setu The following is a partial list of Bapat's other works: Bara Gavache Pani (1967) (A travelogue) Jinkuni Maranala (A biography) Taulanik Sahityabhyas (1981) (A critique) Wisajipantanchi Bakhar (A political parody) Bapat wrote some literature for children, including a play, Bal Govind. The trio of poets Bapat, Vinda Karandikar and Mangesh Padgaonkar provided for many years public recitals of their poetry in different towns in Maharashtra. As an official representative of India, Bapat participated in 1969 in an www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 international poetry conference in Yugoslavia. Bapat served for ten years as an appointed member of Sahitya Akademi in New Delhi. For many years, he was a member of Indian Institute of Mass Communications, also in New Delhi, and Sangeet Natak Academy in Maharashtra. -

Gunidas by G

From boulder!parrikar Tue May 19 20:57:10 MDT 1992 Article: 46958 of soc.culture.indian Newsgroups: soc.culture.indian Path: boulder!parrikar From: [email protected] (Rajan Parrikar) Subject: Great Masters Part XI: Jagannathbuva Purohit Message-ID: <[email protected]> Originator: parrikar@sangria Sender: [email protected] (The Daily Planet) Nntp-Posting-Host: sangria.colorado.edu Organization: University of Colorado, Boulder Date: Wed, 20 May 1992 02:53:14 GMT Lines: 397 Namashkaaram!! Here comes Part XI of the Great Masters series. Once again the feature is taken from G.N. Joshi's book "Down Melody Lane". Rajan ===== ********************************************************************** pp 154-162 of Down Melody Lane My Guru Gunidas by G. N. Joshi Jagannathbuva Purohit - 'Gunidas' - was my Guruji. It is very difficult to express on paper my felings about him. He was kind and honest to the core, and possessed a wealth of new and rare musical compositions. He was very richly gifted, yet he called himself 'Gunidas'- servant of the gifted ones. It was unfortunate that I met him so late in my life. For 10 years I enjoyed his company and we became so close that I regarded him as one of my family. I respected him, stood in awe of him and yet we were bound together by unbreakable bonds of love. I do not quite remember where and when I first met this great man. I think it was around 1956 when I had gone to Manik Varma's house in Pune. He used to come there from Kolhapur a few days every month to give her tuition. -

Customer ID Branch Name 33676 Kochi a Allas 34010 Madurai A

Customer ID Branch Name 33676 Kochi A Allas 34010 Madurai A Sathiah 34884 Mangaluru A c subbegowda 921984 Kochi A J Paily 40359 Coimbatore A m srimuthu Vatchala 930975 Noida A N Buildwell Private Limited 1350646 Madurai A V Sreedharan 33884 Indore Aalok Garg 884459 Pune Aban H Bhandari 598025 Jaipur-Vaishali Abdul Ajij 877477 Kochi Abdul Fazal 880079 Kottayam Abdul Latheef 33596 Mumbai Metro Abdul A A 1279797 Fort Abdul Gani Hajiusman Mundia 527821 Akola Abdul Makin Rabbani Deshmukh 33715 Trivandrum Abdul Rasheed M 1052113 Fort Abdul Sattar Haji Usman Mundia 33509 Mumbai Metro Abhay Madhav Jategaonkar 712156 Jaipur-Vaishali Abhay Singh Shekhawat 755221 Durgapur Abhijit Sarkar 59920 Indore Abraham T m 34455 Hyderabad Adiseshu Kotari 9008702 Mangaluru Adithya D 33587 Mumbai Metro Agarwal J D 33514 Mumbai Metro Ahuja S K 1008032 Ghaziabad Ajay Jain 884189 Bhopal Ajay Sharma 518595 Jaipur-Vaishali Ajay Bahadur Agnihotri 1263354 Mumbai Metro Ajay Motilal Paswan 878707 Kochi Ajisha M 1020955 Thane Ajit Harichandra Rupanwar 33833 Hubballi Ajitkumar Patil 1038513 Durgapur Ajoy Aich 969951 Varanasi Akhilesh Singh 981540 Mumbai Metro Akshata Sandeep Chonkar 876045 Akola Akshay R Mahhalle 33755 Mumbai Metro Alexander P M 1577540 Rajkot Alka B Shah 1264581 Vadodara Alkaben C Suthar 33797 Mumbai Metro Alok Kumar 946731 Durgapur Aloka Nanda Bhyas 895096 Kolkata Aloke Guha 877935 Kochi Amal Raj R 37999 Mumbai Metro Ambarish Krishna Nagarsekar 548180 Solapur Ambika Naganath Kurapati 548162 Solapur Ambika Narendra Jatla 548213 Solapur Ambubai Ambadas Kajle -

DEPT. of MARATHI Syllabus for P.G. in Marathi

RANI CHANNAMMA UNIVERSITY, BELAGAVI DEPT. OF MARATHI Syllabus for P.G. in Marathi (As per CBCS Guidelines) From the academic year 2020-21 to 2021-22 onwards … Revised syllabus for M.A. in Marathi for I to IV Semester under CBCS system from the academic year 2020-21 to 2021-22 onwords… Semester – I Paper 1.1 Madhyayugin Marathi : Gadya/Padya Objectives 1. Pracheen Marathi wangmayacha parichay karun ghene 2. Marathi sahityachi poorpeethika samjun ghene 3. Pracheen Marathi Granthakaranchi olakh karun ghene Topics/Units 1. Madhyayugin Bhakti sampradaya 2. Madhyayugin wangmaya 3. Mahanubhav panth 4. Mahanubhav panthacha achardharm ani tatvavichar 5. Mahandamba Text Books 1. Mahandambeche Dhawale (Padya)- Dr. Suhasini Irlekar, Snehavardhan Prakashan, Pune Practical 1. Hastalikhitanche swaroop pahun lekhan karane 2. Handibhadanganath ani belemath Aadi pracheen mathana bhet dene. Reference Books 1. Mahanubhav Panth ani tyanche wangmaya-S.G.Tulpule, Venus Prakashan, Pune. 2. Mahanubhav Sahitya- Sourabh – Dr. Ramesh Awalgaonkar Sarvadnya Veedyapeeth Prakashan, Pune 3. Mahanubhav Sanshodhan –V.B.Kolate, Arun Prakashan, Malkapur. 4. Mahanubhavancha achardharma - V.B.Kolate, Arun Prakashan, Malkapur. 5. Paanch Bhaktisampraday –R.R.Gosavi Moghe, Prakashan, Kolhapur 6. Pracheen Marathi Wangmayacha Itihaas-A.N.Deshpande, Venus Prakashan Pune 7. Madhyayugin Marathi Sahityavishayi-Dr. Satish Badave, Meera Books & Publications, Aurangabad. 8. Mahadamba: Adya Marathi Kavayitri-V.N. Deshpande, Continental Prakashan, Pune 9. Mahadambeche Dhavale:Sahitya ani Sameeksha-Madan Kulkarni, Piplapure Prakashan,Nagpur Paper 1.2 Streevadi Sahitya Objectives 1. Streevadi sahityachi olakh karun ghene 2. Marathitil streevadi sahityacha parchaya ghene 3. Streevadi sahityache yogadan abhyasane Topics/Units 1. Streevadi Sahitya : Sankalpana ani swaroop 2. Streevadi Sahityachi Chalawal 3. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Vivian Liff, George Stuart and Their Incredible Gift to the Ncpa

July 2018 ON Stagevolume 7 • issue 12 VIVIAN LIFF, GEORGE STUART AND THEIR INCREDIBLE GIFT TO THE NCPA CHATURANG KI CHAUPAL Kathak on the Chaupal NONA Winner of four METAs NCPA Chairman Khushroo N. Suntook Executive Director & Council Member Deepak Bajaj Editorial Director Radhakrishnan Nair Editor-in-Chief Oishani Mitra Contents Consulting Editor Ekta Mohta Senior Sub-editor 12 Cynthia Lewis Editorial Co-ordinator Hilda Darukhanawalla Art Director Amit Naik Deputy Art Directors Hemali Limbachiya Tanvi Shah Graphic Designer Vidhi Doshi Advertising Anita Maria Pancras ([email protected]; 66223820) Tulsi Bavishi ([email protected]; 9833116584) Senior Digital Manager Jayesh V. Salvi Published by Deepak Bajaj for The National Centre for the Performing Arts, NCPA Marg, Nariman Point, Mumbai – 400021 Produced by Editorial Office 4th Floor, Todi Building, Mathuradas Mills Compound, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai - 400013 Features Printer Spenta Multimedia, Peninsula Spenta, Mathuradas Mill Compound, N. M. Joshi Marg, Lower Parel, 08 Mumbai – 400013 Reflections 14 On the importance of humanities. Kathak on the Chaupal Materials in ON Stage cannot be reproduced in By Anil Dharker It was a casual anecdote from Birju part or whole without the written permission Maharaj over two decades of the publisher. Views and opinions expressed ago that led to the creation of in this magazine are not necessarily those of 10 Chaturang Ki Chaupal. By Library of Voices the publisher. All rights reserved. Shama Bhate If you’re even remotely interested in opera, NCPA Booking Office there are few starting points better than the 2282 4567/6654 8135/6622 3724 Stuart-Liff Collection, housed at the NCPA. -

Annual Report

NATIONAL SCHOOL OF DRAMA jk"Vªh; ukV~; fo|ky; ANNUAL REPORT okf"kZd çfrosnu 0 2 - 9 1 0 2 okf"kZd çfrosnu Annual Report 2019-20 Annual Report 2019-20 jk"Vªh; ukV~; fo|ky; National School of Drama Contents NSD : An Introduction 3 Organizational Set-up & Meetings during 2019-20 4 Authorities and Officers of the School 5 Director and other Teaching Staff 6 Training at the National School of Drama 7 Technical Departments 9 Library 10 Highlights 2019-20 13 Other Activities 17 Academic Activities 23 Apprentice Fellowship awarded for the academic year 2019-20 to NSD graduate 36 Students’ Productions 38 Cultural Exchange Programme (CEP) 49 Repertory Company 51 Sanskaar Rang Toli (TIE) 54 National School of Drama Extension Programme 62 RajbhashaVibhag 64 Publication Programme 66 NSD Bengaluru Centre 69 NSD Sikkim Theatre Training Centre, Gangtok 80 NSD Theatre-in-Education Centre, Agartala, Tripura 82 NSD Varanasi Centre 91 Staff strength 97 NSD Resource Position at a Glance 99 National School of Drama National School of Drama (NSD) one of the foremost theatre institutions in the world and the only one of its kind in India was set up by Sangeet Natak Akademy in 1959. Later in 1975, it became an autonomous organization, fully financed by Ministry of Culture, (MoC) Government of India. The objective of NSD is to develop suitable patterns of teaching in all branches of drama both at undergraduate and post-graduate levels so as to establish high standards of theatre education in India. After graduation, the NSD offers a theatre training programme of three years' duration. -

Conceptualising Popular Culture ‘Lavani’ and ‘Powada’ in Maharashtra

Special articles Conceptualising Popular Culture ‘Lavani’ and ‘Powada’ in Maharashtra The sphere of cultural studies, as it has developed in India, has viewed the ‘popular’ in terms of mass-mediated forms – cinema and art. Its relative silence on caste-based cultural forms or forms that contested caste is surprising, since several of these forms had contested the claims of national culture and national identity. While these caste-based cultural practices with their roots in the social and material conditions of the dalits and bahujans have long been marginalised by bourgeois forms of art and entertainment, the category of the popular lives on and continues to relate to everyday lives, struggles and labour of different classes, castes and gender. This paper looks at caste-based forms of cultural labour such as the lavani and the powada as grounds on which cultural and political struggles are worked out and argue that struggles over cultural meanings are inseparable from struggles of survival. SHARMILA REGE he present paper emerged as a part tested and if viewed as a struggle to under- crete issues of the 1970s; mainly the re- of two ongoing concerns; one of stand and intervene in the structures and sistance of British working class men and Tdocumenting the regional, caste- processes of active domination and sub- youth, later broadening to include women based forms of popular culture and the ordination, it has a potent potential for and ethnic minorities. By the 1980s cul- other of designing a politically engaged transformative pedagogies in regional tural studies had been exported to the US, course in cultural studies for postgraduate universities.